Alfred Wegener

Alfred Wegener | |

|---|---|

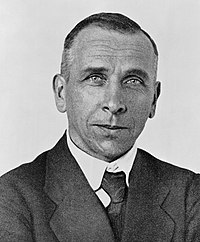

Alfred Wegener, about 1925 | |

| Born | 1 November 1880 |

| Died | 13 November 1930 |

| Nationality | German |

| Alma mater | University of Berlin |

| Known for | continental drift |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | meteorology geology |

Alfred Lothar Wegener (1 November 1880 – 13 November 1930) was a German scientist, geophysist and meteorologist.[1] He is most notable for his theory of continental drift, which he proposed in December 1912.[2][3] This was the idea that the continents were slowly drifting around the Earth. He also had ideas about why the continents drift, which other scientists thought were impossible. His hypothesis was not accepted until the 1950s. Then several discoveries gave evidence of continental drift,[4] and of the actual causes.

Wegener was born in Berlin and in 1904 he earned his PhD in Astronomy at the University of Berlin. As a reserve officer of the German Army he was called up in 1914 to fight in World War I. He was severely wounded in Belgium and transferred to the army weather service. After the war he mainly did weather work.

Plate tectonics theory[change | change source]

The theory had been proposed before, more than once. The first time was by the mapmaker Abraham Ortelius in the 16th century.[5]

Wegener's theory[change | change source]

Wegener used geologic, fossil, and glacial evidence from opposite sides of the Atlantic Ocean to support his theory of continental drift. For example, he said that there were geological similarities between the Appalachian Mountains in North America, and the Scottish Highlands. Also, he said that the rock strata in South Africa and Brazil were similar.[6]

He believed these similarities could be explained only if these geologic features were once part of the same continent. Wegener said that because they are less dense, continents float on top of the denser rock of the ocean floor, and move across the ocean floor rock. Although continental drift explained many of Wegener's observations, he could not find scientific evidence to make a complete explanation of how continents move.[6]

Criticism[change | change source]

The British geologist Arthur Holmes championed the theory of continental drift at a time when it was unfashionable. He proposed in 1931 that the Earth's mantle contained convection cells that dissipated radioactive heat and moved the crust at the surface.[7] His Principles of Physical Geology, ending with a chapter on continental drift, was published in 1944.[8]

However, most Earth scientists and palaeontologists did not believe Wegener's theory and thought it was foolish.[6] Some critics thought that giant land bridges could explain the similarities among fossils in South America and Africa.[6] Others argued that Wegener's theory did not explain the forces that would have been needed to move continents to such great distances. Wegener thought that the forces that moved the continents could be caused by the rotation of the Earth and stellar precession and that same forces made earthquakes and volcanic eruptions.[6]

Evidence[change | change source]

During the 1950s, in the mid-atlantic ridge discoveries of sea-floor spreading and magnetic reversal proved that Wegener's theory was real and led to the theory of plate tectonics, though his proposed causes were mistaken. Today geologists say that continents are actually parts of moving tectonic plates that float on the asthenosphere, a layer of partly molten rock.[6]

References[change | change source]

- ↑ "Alfred Wegener". ucmp.berkeley.edu. Retrieved 4 December 2010.

- ↑ Wegener, Alfred 1912. Die Entstehung der Kontinente. Geologische Rundschau (in German) 3 (4): 276–292.

- ↑ Wegener, Alfred 1966. The origin of continents and oceans. New York: Dover. ISBN 0-486-61708-4. Translated from the fourth revised German edition by John Biram.

- ↑ Spaulding, Nancy E. and Samuel N. Namowitz. 2005. Earth Science. Boston: McDougal Littell.

- ↑ Kious W.J. & Tilling R.I. 2001 [1996]. Historical perspective, in This dynamic Earth: the story of plate tectonics. U.S. Geological Survey. ISBN 0-16-048220-8 [1]

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 Earth Science. United States of America: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. 2001. p. 211. ISBN 0-03-055667-8.

- ↑ Holmes, Arthur (1931). "Radioactivity and Earth Movements" (PDF). Trans. Geological Society of Glasgow. 18 (3): 559–606. doi:10.1144/transglas.18.3.559. S2CID 122872384. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-10-09. Retrieved 2014-07-29.

- ↑ Holmes, Arthur (1944). Principles of Physical Geology (1st ed.). Edinburgh: Thomas Nelson & Sons. ISBN 0-17-448020-2.