Brown dwarf

A brown dwarf is an object which is made of the same stuff as stars, but does not have enough mass for hydrogen fusion (combining hydrogen atoms into helium atoms). Hydrogen fusion is what makes stars glow. Brown dwarfs are not massive enough to do this, so they are not stars. On the other hand, they are not regular giant planets, because they do glow. There are probably lots of them, but few have been found because they have only a very dim glow.

Their mass is between the heaviest gas giants and the lightest stars, with an upper limit around 75 to 80 times the mass of Jupiter (MJ).[1] Brown dwarfs more massive than 13 MJ are thought to fuse deuterium and those above ~65 MJ, fuse lithium as well.[2]

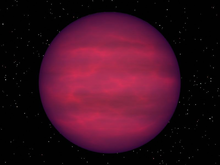

Despite their name, most brown dwarfs would appear magenta to the human eye.[3] The nearest known brown dwarf is WISE 1049-5319 about 6.5 light years away, a binary system of brown dwarves discovered in 2013.

Discovery[change | change source]

People first guessed that brown dwarfs might exist in the 1960s, before they were discovered.[3] People came up with many different names for these theoretical objects, including planetar and substar. Brown dwarfs stayed hypothetical for decades.

Early theories suggested that an object less than 0.09 solar masses would never go through normal stellar evolution. The discovery of deuterium-burning down to 0.012 solar masses and the impact of dust formation in the cool outer atmospheres of brown dwarfs in the late 1980s brought these theories into question. However, such objects were hard to find because they emit almost no visible light. Their strongest emissions are in the infrared (IR) spectrum, and ground-based IR detectors were too imprecise at that time to readily identify any brown dwarfs.

For many years, efforts to discover brown dwarves were fruitless. In 1988, however, GD 165B was discovered, showing none of the features expected of a low-mass red dwarf star. Today, GD 165B is recognized as the prototype of a class of objects now called "L dwarfs". Although the discovery of the coolest dwarf was highly significant at the time, it was debated whether GD 165B would be classified as a brown dwarf or simply a very-low-mass star, because observationally it is very difficult to distinguish between the two.

Soon after the discovery of GD 165B, other brown-dwarf candidates were reported. Most failed to live up to their candidacy, however, because the absence of lithium showed them to be stellar objects. True stars will burn their lithium within a little over 100 million years (my), whereas brown dwarfs will not. Confusingly, brown dwarves have temperatures and luminosities similar to some true stars. In other words, the detection of lithium in the atmosphere of an object means that, if it is older than 100 my, it is a brown dwarf.

In 1994/5 the study of brown dwarfs changed with the discovery of two definite substellar objects (Teide 1 and Gliese 229B).

The first confirmed brown dwarf was discovered in 1994.[4] They called this object Teide 1 and it was found in the Pleiades open cluster.[5] Nature highlighted "Brown dwarfs discovered, official" in the front page of that issue. The distance, chemical composition, and age of Teide 1 was established because it is in the young Pleiades star cluster. Teide 1's mass is 55 times that of Jupiter, and clearly below the stellar-mass limit.

More notable was Gliese 229B, which was found to have a temperature and luminosity well below the stellar range. Remarkably, its near-infrared spectrum clearly exhibited a methane absorption band at 2 micrometres, a feature that had previously only been observed in the atmospheres of giant planets and that of Saturn's moon Titan. This discovery helped to establish yet another spectral class even cooler than L dwarfs, known as "T dwarfs", for which Gliese 229B is the prototype.

A brown dwarf below 65 Jupiter masses is unable to burn lithium by thermonuclear fusion at any time during its evolution. High-quality spectral data showed that Teide 1 had kept the initial lithium amount of the original molecular cloud from which Pleiades stars formed. This proved the lack of thermonuclear fusion in its core.

Teide 1 was considered for some time the smallest object out of the Solar System that had been identified by direct observation. Since then over 1800 brown dwarfs have been identified.[6] Some are very close to Earth such as Epsilon Indi Ba and Bb, a pair of brown dwarfs gravitationally bound to a sunlike star around 12 light-years from the Sun, and WISE 1049-5319 a binary system of brown dwarfs about 6.5 light-years away.

Issues[change | change source]

For some years now there has been debate concerning what criterion to use for defining the separation between a very-low-mass brown dwarf and a giant planet (~13 Jupiter masses).[3] One school of thought is based on formation, and another on interior physics.[3]

References[change | change source]

- ↑ Boss, Alan (2001). "Are they planets or what?". Carnegie Institution of Washington. Archived from the original on 2006-09-28. Retrieved 2006-06-08.

- ↑ Nicholos Wethington (2008). "Dense exoplanet creates classification calamity". Universe Today. Retrieved January 30, 2013.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 "Burgasser A.J. 2008. Brown dwarfs: failed stars, super Jupiters" (PDF). Retrieved 2013-03-16.

- ↑ "Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias, IAC". Iac.es. Retrieved 2013-03-16.

- ↑ Rebolo, R.; Osorio, M. R. Zapatero; Martín, E. L. (1995-09-14). "Discovery of a brown dwarf in the Pleiades star cluster". Nature. 377 (6545). Nature.com: 129–131. doi:10.1038/377129a0. S2CID 28029538. Retrieved 2013-03-16.

- ↑ Gelino, Chris; Kirkpatrick, Davy & Burgasser, Adam 2012. DwarfArchives.org: Photometry, spectroscopy, and astrometry of M, L, and T dwarfs. caltech.edu. [1] Archived 2019-05-11 at the Wayback Machine