Chondrichthyes

| Cartilaginous fishes | |

|---|---|

| |

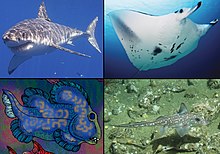

| Example of cartilaginous fishes : at the top of the image, Elasmobranchii and at the bottom of the image, Holocephali. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Subphylum: | Vertebrata |

| Infraphylum: | Gnathostomata |

| Clade: | Eugnathostomata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes Huxley, 1880 |

| Subclasses and Orders | |

| |

Chondrichthyes or cartilaginous fishes are the sharks and their relatives. They have jaws and paired fins, paired nostrils, scales, two-chambered hearts, and skeletons made of cartilage rather than bone. They are divided into two subclasses: Elasmobranchii (sharks, rays and skates) and Holocephali (chimaera, sometimes called ghost sharks).

Taxonomy[change | change source]

- Class Chondrichthyes

- Subclass Elasmobranchii (sharks, rays and skates)

- Superorder Batoidea (rays and skates), containing the orders:

- Rajiformes (common rays and skates)

- Pristiformes (Sawfishes)

- Torpediniformes (electric rays)

- Superorder Selachimorpha (sharks), containing the orders:

- Hexanchiformes There are two families in this order. Species of this order are distinguished from other sharks by having additional gill slits (either six or seven). Examples from this group include the cow sharks, frilled shark and even a shark that looks on first inspection to be a marine snake.

- Squaliformes There are three families and more than 80 species in this order. These sharks have two dorsal fins, often with spines, and no anal fin. They have teeth designed for cutting in both the upper and lower jaws. Examples from this group include the bramble sharks, dogfish and roughsharks.

- Pristiophoriformes There is one family in this order. These are the sawsharks, with an elongate, toothed snout that they use for slashing the fishes that they then eat.

- Squatiniformes There is one family in this order. These are flattened sharks that can be distinguished from the similar appearing skates and rays by the fact that they have the gill slits along the side of the head like all other sharks. They have a caudal fin (tail) with the lower lobe being much longer in length than the upper, and are commonly referred to as angel sharks.

- Heterodontiformes There is one family in this order. They are commonly referred to as the bullhead, or horn sharks. They have a variety of teeth allowing them to grasp and then crush shellfish.

- Orectolobiformes There are seven families in this order. They are commonly referred to as the carpet sharks, including zebra sharks, nurse sharks, wobbegongs and the largest of all fishes, the whale sharks. They are distinguished by having barbels at the edge of the nostrils. Most, but not all are nocturnal.

- Carcharhiniformes There are eight families in this order. It is the largest order, containing almost 200 species. They are commonly referred to as the groundsharks, and some of the species include the blue, tiger, bull, reef and oceanic whitetip sharks (collectively called the requiem sharks) along with the houndsharks, catsharks and hammerhead sharks. They are distinguished by an elongated snout and a nictitating membrane which protects the eyes during an attack.

- Lamniformes There are seven families in this order. They are commonly referred to as the mackerel sharks. They include the goblin shark, basking shark, megamouth, the thresher, mako shark and great white shark. They are distinguished by their large jaws and ovoviviparous reproduction. The Lamniformes contains the extinct Megalodon (Carcharodon megalodon), which like most extinct sharks is only known by the teeth (the only bone in these cartilaginous fishes, and therefore are often the only fossils produced). A reproduction of the jaw was based on some of the largest teeth (up to almost 7 inches in length) and suggested a fish that could grow 120 feet in length. The jaw was realized to be inaccurate, and estimates revised downwards to around 50 feet.

- Superorder Batoidea (rays and skates), containing the orders:

- Subclass Holocephali (chimaera)

- Subclass Elasmobranchii (sharks, rays and skates)

References[change | change source]

Wikispecies has information on: Chondrichthyes.

- ↑ Botella, H.A.; Donoghue, P.C.J.; Martínez-Pérez, C. (2009). "Enameloid microstructure in the oldest known chondrichthyan teeth". Acta Zoologica. 90 (Supplement): 103–108. doi:10.1111/j.1463-6395.2008.00337.x.

- ↑ "Chondrichthyes". PalaeoDB. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 26 November 2013.