Kit Carson

Kit Carson | |

|---|---|

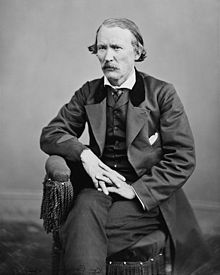

Carson on a visit to Washington, DC, in early 1868 | |

| Born | December 24, 1809 |

| Died | May 23, 1868 (aged 58) Fort Lyon, Colorado |

| Resting place | Kit Carson Cemetery Taos, New Mexico |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation(s) | Mountain man, frontiersman, guide, Indian agent, US Army officer |

| Known for | Opening the American West to European settlement Carson City, Nevada namesake |

| Spouses |

|

| Allegiance | Union |

| Service/branch | Union Army |

| Rank | Brevet Brigadier General |

| Commands held | 1st New Mexico Volunteer Cavalry Regiment |

| Battles/wars | Mexican–American War |

| Signature | |

Christopher Houston "Kit" Carson, (December 24, 1809 – May 23, 1868) was an American frontiersman, a career that involved four chief occupations: mountain man, guide, Indian agent, and officer in the US Army. He helped to open the American West to settlement. In his day, he was a celebrity known far and wide in the United States. In modern America, he is still remembered as a folk hero, but he has been criticized for killing Native Americans.

Carson began his adult life in 1829 as a mountain man, who trapped beaver about ten years for the fur trade. During those years, Carson became an "Injun killer" — he was forced to kill many Native Americans to protect himself from attack, theft, and murder. Carson became known as one of the greatest of "Injun killers" through novels, newspaper accounts, and other media. When the fur trade died out in the 1840s, Carson looked for other work.

In 1842, US Army Officer John Charles Frémont hired Carson to guide him on three separate expeditions into the West. All three expeditions involved mapping and describing remote and uncharted areas of the West. The expeditions were hugely successful. Frémont's reports to the government made Carson a frontier hero and were read by many Americans. Carson became a celebrity throughout the country. His adventures were turned into stories that were published in paper-covered books, called dime novels. The cheap popular books made him more famous than ever.

In 1853, Carson became an Indian agent in northern New Mexico. His job was to keep the Utes and the Apaches at peace. He saw to it that they were treated with honesty and fairness and that they got the food and clothing that they needed. In 1861, the American Civil War broke out. Carson resigned his position as Indian agent, and joined the Union Army. As a lieutenant, he led the New Mexico Volunteer Infantry. His forces fought Confederates at Valverde, New Mexico. The Confederates won the battle, but were later defeated. Most of Carson's time in the army was passed training recruits.

Carson served in several wars and battles with the tribes In the Southwest. He rounded up and moved Apaches and Navajos from their homelands to government lands called reservations. Carson was promoted to the rank of colonel. Late in life, he was promoted to brigadier general and given command of Fort Garland in Colorado. After about two years. Carson left the military because of illness. He died in 1868 at Fort Lyon, Colorado. He is buried in Taos, New Mexico, next to his third and last wife, Josefa Jaramillo.

Personal description[change | change source]

Carson was described by his contemporaries as a "small, stooped-shoulder" man with brown to red hair, blue eyes, and a strong but spare frame. He was said to be about 5 foot 7 inches. He was a modest gentleman. Most of his contemporaries were astonished that such a slight inconspicuous man had accomplished so much among the Native Americans and wild animals on the western frontier.

General William Tecumseh Sherman[change | change source]

In 1847, General William Tecumseh Sherman met Kit Carson in Monterey, California. Sherman wrote: "His fame was then at its height,... and I was very anxious to see a man who had achieved such feats of daring among the wild animals of the Rocky Mountains, and still wilder Indians of the plains.... I cannot express my surprise at beholding such a small, stoop-shouldered man, with reddish hair, freckled face, soft blue eyes, and nothing to indicate extraordinary courage of daring. He spoke but little and answered questions in monosyllables."[1]

Colonel Edward W. Wynkoop[change | change source]

Colonel Edward W. Wynkoop wrote: "Kit Carson was five feet five and one half-inches tall, weighed about 140 pounds, of nervy, iron temperament, squarely built, slightly bow-legged, and those members apparently too short for his body. But, his head and face made up for all the imperfections of the rest of his person. His head was large and well-shaped with yellow straight hair, worn long, falling on his shoulders. His face was fair and smooth as a woman's with high cheekbones, straight nose, a mouth with a firm, but somewhat sad expression, a keen, deep-set but beautiful, mild blue eye, which could become terrible under some circumstances, and like the warning of the rattlesnake, gave notice of attack. Though quick-sighted, he was slow and soft of speech, and posed great natural modesty."[1]

Lieutenant George Douglas Brewerton[change | change source]

Lieutenant George Douglas Brewerton made a coast-to-coast dispatch-carrying trip to Washington, DC, with Carson. Brewerton wrote: "The Kit Carson of my imagination was over six feet high — a sort of modern Hercules in his build — with an enormous beard, and a voice like a roused lion.... The real Kit Carson I found to be a plain, simple... man; rather below the medium height, with brown, curling hair, little or no beard, and a voice as soft and gentle as a woman's. In fact, the hero of a hundred desperate encounters, whose life had been mostly spent amid wilderness, where the white man is almost unknown, was one of Dame Nature's gentleman...."[2]

Illiteracy[change | change source]

Carson was illiterate. He was embarrassed by not being able to read and write and so tried to hide it. He was impressed by gentlemen who could read and write, however.[3] In 1856, he told his life story to an army officer, who wrote it down. Carson told the officer that he had left school at an early age: "I was a young boy in the school house when the cry came, Injuns! I jumped to my rifle and threw down my spelling book, and thar it lies."

Carson enjoyed having other people read to him. He liked the poetry of Lord Byron. Carson thought Sir Walter Scott's long poem The Lady of the Lake was "the finest expression of outdoor life."[4] He also liked a book about William the Conqueror, whose favorite oath was "By the splendor of God." Carson used that oath as his own and was known to have Nevers used anything stronger.[1]

Carson learned to write "C. Carson" late in life, but it was very difficult for him. He made his mark on official papers, and the mark was then witnessed by a clerk.[5] Carson easily spoke English, Spanish, and French. He could speak many Native American languages, including Navajo, Apache, and Comanche. He also knew the sign language that was used by mountain men.[1] Very late in life, he learned to read to a certain extent and to recognize his name when it appeared in print.

Early life[change | change source]

Carson was born in Kentucky, but his family moved to Missouri when he was a baby. In Missouri, the family was in danger from Native American attacks and had to find ways to protect themselves. After his father's death in 1818, Kit's mother remarried. The boy became a wild teenager. His stepfather put him to work in a saddle-making shop in Franklin, Missouri.

Kentucky[change | change source]

Carson was born in a log cabin at Tate's Creek, Madison County, Kentucky on Christmas Eve 1809.[1][6] His parents were Lindsay (or Lindsey) Carson and his second wife, Rebecca Robinson. Lindsay had had five children by his first wife, Lucy Bradley, and ten more children by Rebecca. Kit was their sixth.[7][8][9]

Lindsay Carson had a Scots-Irish Presbyterian background.[10] He was a farmer, a cabin builder, and a veteran of the American Revolutionary War and the War of 1812.[1][8] He also fought Native Americans on the frontier. Two fingers on his left hand were shot away in a battle with the Sauk and Fox tribes.[11]

Missouri[change | change source]

The Carsons moved to Boone's Lick, Howard County, Missouri, when Kit was about one year old. They knew Daniel Boone's family. Lindsay's oldest son, William, married Boone's grandniece, Millie Boone, in 1810. Their daughter, Adaline, became Kit's favorite playmate.[1][12]

Defenses from attacks[change | change source]

The Carson family was always in danger of Native American attacks in Missouri and so had to be alert. Cabins were "forted:" they had tall fences built around them, called stockades, to make the people inside Them safe from attack. During the day, men worked in the fields near the cabins. Some men had weapons to protect the workers and were ready to kill any Native American who attacked.[13][14] Carson wrote in his Memoirs: "For two or three years after our arrival, we had to remain forted and it was necessary to have men stationed at the extremities of the fields for the protection of those that were laboring."[5]

Death of Lindsay Carson[change | change source]

One day in 1818, Lindsay Carson was clearing a field when a tree limb fell on him. He was killed instantly when Kit was about eight years old. His mother took care of her children alone for four years. They lived in great poverty. She then married Joseph Martin, a widower with several children.[1][15]

Apprenticeship[change | change source]

Carson did not get along with his stepfather and became a wild and uncontrollable teenager. His stepfather apprenticed him to David Workman, a saddle maker in Franklin, Missouri. Kit was a boy in his mid-teens and wrote in his Memoirs that Workman was "a good man, and I often recall the kind treatment I received."[1][16]

Runaway[change | change source]

Carson did not like making saddles and ran away from home in 1826. He traveled over the Santa Fe Trail with mountain men. In 1829, he joined with trapper Ewing Young on a trek to the Rocky Mountains. He learned much from Young about trapping.

Turned mountain man[change | change source]

Franklin, Missouri, was at the eastern end of the Santa Fe Trail and was a starting point for many settlers heading west. Carson heard wonderful stories about the West from the mountain men returning to the East.[1] In August 1826, he ran away from home, and went West with the mountain men. They traveled over the Santa Fe Trail to Santa Fe, New Mexico, and reached their destination in November 1826. Kit passed the winter in Taos, New Mexico, with Mathew Kinkead, a mountain man and a neighbor from Missouri. Taos would become Carson's home.[17][18]

Workman posts a reward[change | change source]

Workman put an advertisement in a local newspaper back in Missouri. He wrote that he would give a one cent reward to anyone who brought the boy back to Franklin. No one claimed the reward. It was a bit of a joke, but Carson was free.[19] The advertisement featured the first printed description of Carson: "Christopher Carson, a boy about 16 years old, small of his age, but thick set; light hair, ran away from the subscriber, living in Franklin, Howard county, Missouri, to whom he had been bound to learn the saddler's trade."[19]

Between 1827 and 1829, Carson worked as cook, translator, and wagon driver in the Southwest. He also worked at a copper mining|mine near the Gila River, in southwestern New Mexico.[7][20] In later life, Carson never mentioned any women from his youth. There are only three specific women mentioned in his writing: Josefa Jaramillo, his third and last wife; a comrade's mother in Washington, DC; and Mrs. Ann White, a victim of Native American atrocities.[21]

Ewing Young and Thomas Fitzpatrick[change | change source]

In August 1829, the 19-year-old Carson joined trapper Ewing Young and his mountain men on a fur- hunting expedition to Arizona and California. That was Carson's first professional job as a mountain man. Carson received much experience as a trapper on the expedition. Young is credited with shaping Carson's early life in the mountains.

Carson returned to Taos in 1829 and joined a wagon train rescue party. Although the perpetrators had fled the scene of atrocities, Young had the opportunity to witness Carson's horsemanship and courage. Kit passed the winter of 1827-1828 as Young's cook in Taos.[22] Carson joined another expedition led by Thomas Fitzpatrick in 1831. Fitzpatrick and his trappers went north to the central Rocky Mountains. Carson would hunt and trap in the West for about ten years. He was known as a reliable man and a good fighter.[7][23]

Mountain man[change | change source]

Carson traveled through many parts of the American West to gather furs. Men at the time wore hats made of beaver fur. He trapped beaver for the fur trade and sometimes worked with famous mountain men like Jim Bridger and Old Bill Williams.[1][7]

Career[change | change source]

Carson's career as a mountain man began in 1829, when he joined Ewing Young's trapping expedition to the Rocky Mountains. Mountain men worked mostly in the Rocky Mountains for themselves, sometimes with a partner or two, or for a large trading organization like the Hudson's Bay Company.

A mountain man's life was not easy. He sometimes had to walk into deep cold water to get a trapped beaver. He then had to remove the hide with the fur, yhe pelt. The mountain man kept the beaver pelts for many months and then sold them in St. Louis, Missouri, or at a mountain man rendezvous. With the money that he collected, he bought fish hooks, flour, tobacco, and the other things that he needed for life in the mountains.

Hazards and hardships[change | change source]

The mountain man faced many hazards including biting insects, bad weather, and diseases of all kinds. There were no doctors in the lands on which mountain men worked. The man had to set his own broken bones, tend his wounds, and nurse himself.[24] Native Americans were an ever-present danger since even friendly ones could turn at once into an enemy.[25] A mountain man usually had a Native American wife or mistress.[26] His main food was buffalo.[27] Je was dressed in deer skins that had stiffened by being left outdoors for a time. The suit of stiffened deer skin gave him some protection from the weapons of his enemies.[28]

Grizzly bears[change | change source]

Grizzly bears were one of the mountain man's greatest enemies.[29] Carson stated in his Memoirs that he was hunting an elk alone in 1834. Two grizzly bears chased him up a tree. One bear tried to make him fall by shaking the tree. The bear was not successful and finally went away. Carson returned to his camp as fast as he could. He stated that the incident had been the scariest moment of his life: "[The bear] finally concluded to leave, of which I was heartily pleased, never having been so scared in my life."[30]

Rendezvous[change | change source]

Mountain men met every year in the second quarter of the 19th century for an event called a rendezvous.[31] The first rendezvous was held in 1825.[32] Those events were held in remote areas of the West like the banks of the Green River in Wyoming. A mountain man had a good time at those lively events. Native Americans often joined the gathering. Everyone played card games, danced, sang, told stories, made jokes, and had much to eat and drink. Sometimes, mountain men married Native American women at a rendezvous. The last rendezvous was held in 1840.[33][34]

Decline of fur trade[change | change source]

About 1840, the fur trade began to drop off. Well-dressed men in London, Paris, and New York City wanted silk hats instead of beaver hats. In addition, the mountain men had very nearly killed almost every beaver in North America. Trappers were no longer wanted or needed. The mountain man Robert Newell told Jim Bridger: "[W]e are done with this life in the mountains — done with wading in beaver dams, and freezing or starving alternately — done with Indian trading and Indian fighting. The fur trade is dead in the Rocky Mountains, and it is no place for us now, if ever it was."[35][36]

Meat hunter at Bent's Fort[change | change source]

Carson knew that it was time to find other work. He stated in his Memoirs, "Beaver was getting scarce, it became necessary to try our hand at something else." In 1841, he was hired at Bent's Fort in Colorado. The fort was one of the greatest buildings in the West. Hundreds of people worked or lived there. Carson hunted buffalo, antelope, deer, and other animals to feed the hundreds of people. He was paid one dollar a day. He returned to Bent's Fort several times during his life to again provide meat for the fort's residents. In April 1842, Carson went back to his childhood home in Missouri. He made the trip to put his daughter, Adaline, in the care of relatives.[37]

Indian fighter/"Injun killer"[change | change source]

Carson found much pleasure in killing Native Americans. He did not respect them and thought that those who committed outrages like murder, theft, and rape deserved the worst punishment possible. Carson's thoughts about Native Americans softened over the years, as he found himself more and more in their company. He became an Indian agent and a spokesman for the Utes.

First years[change | change source]

Carson was 19 when he set off with Ewing Young's expedition to the Rocky Mountains. In addition to furs and the company of free-spirited rugged mountain men, he sought action and adventure. He found what he was looking for in killing and scalping Native Americans. Carson probably killed and took the scalp of his first Native American when he was 19 years old, during Ewing Young's expedition.[38] Carson was known to most 19th+century Americans as an "Injun killer," chiefly through newspaper accounts and dime novels. Many of the works gave Carson's deeds and life a romantic cast. Excitement and thrills were heightened through exaggeration.

Carson hated Native Americans, especially those who had committed crimes such as rape, theft, and murder. He believed that Native Americans could not be trusted, and should be punished. Mountain men often had to kill Native Americans to save their own lives.[6][7] The young Carson's brutal and vicious notions about Native Americans is sometimes considered his greatest moral failing.[39] Carson never killed Native American women and children, however. He believed that a brave man would never do so, and he scorned the men who did.

Crow tribe[change | change source]

Carson's Memoirs are replete with stories about Native American encounters with the memoir writer. In January 1833, for example, warriors of the Crow tribe stole nine horse from Carson's camp. Carson and 11 other men found the Crow camp after dark and quietly led the horses away. The men who owned the horses wanted to return to their own camp at once. Although Carson and two other men had not lost any horses, the three wanted to punish the Crows. Carson and his men fired their guns into the Crow camp and killied almost every Crow. Carson wrote in his Memoirs: "During our pursuit for the lost animals, we suffered considerably but, the success of having recovered our horses and sending many a redskin to his long home, our sufferings were soon forgotten."[40]

Blackfoot nation[change | change source]

The Blackfoot nation was a hostile tribe and posed an ever-present threat to Carson's safety. A Blackfoot warrior once injured Carson in the shoulder. That was the worst injury he received in his life. He hated the Blackfeet and killed them at every opportunity. The historian David Roberts wrote: "It was taken for granted that the Blackfeet were bad Indians; to shoot them whenever he could was a mountain man's instinct and duty."[41] The Blackfeet did not like whites, Who, they were convinced were trying to take over their hunting grounds. In addition, the Blackfeet wanted the valuable horses that were owned by the whites.[7]

Carson had several encounters with the Blackfeet, but his last battle with them took place in spring 1838. He was traveling with about 100 mountain men, led by Jim Bridger. In Montana Territory, the group found a teepee with three Native American corpses inside. The three had died of smallpox. Bridger wanted to move on, but Carson and the other young men wanted to kill the Blackfeet.

They found the Blackfoot village, and killed ten Blackfeet warriors. The Blackfeet found some safety in a pile of rocks but were driven away. It is not known how many Blackfeet died in that incident. The historian David Roberts wrote that "if anything like pity filled Carson's breast as, in his twenty-ninth year, he beheld the ravaged camp of the Blackfeet, he did not bother to remember it." Carson wrote in his Memoirs that this battle was "the prettiest fight I ever saw."[42]

Change of beliefs[change | change source]

Carson's notions about Native Americans softened over the years. He found himself more and more in their company as he grew older. His thoughts about Native Americans became more understanding and more humane.[7] He urged the government to set aside lands, called reservations, for their use. As an Indian agent, he saw to it that those under his watch were treated with honesty and fairness and were clothed and fed properly. The historian David Roberts believes that his first marriage to an Arapaho women, named Singing Grass, "softened the stern and pragmatic mountaineer's opportunism."[30]

Manifest Destiny[change | change source]

In killing Native Americans, Carson was making America safe for settlers heading west to build their homes, farms, and villages. He had the approval of the US government and its citizens.[7] In addition, Senator Thomas Hart Benton, the United States Congress, and President James K. Polk had developed and were working under a concept called Manifest Destiny, which stated that it was the will of God that the United States push America's western boundary to the Pacific Ocean at all costs. That spurred the movement of American settlers to the West.

Personal life[change | change source]

Carson was married three times. His first two wives were Native Americans. His third wife was Mexican. He was the father of ten children. Carson never wrote about his first two marriages in his Memoirs. He may have thought he would be known as a "squaw man". Such men were not welcomed by polite society.[43]

Waanibe[change | change source]

In 1836, Carson met an Arapaho woman named Waanibe (Singing Grass) at a mountain man rendezvous. This rendezvous was held along the Green River in Wyoming. Singing Grass was a lovely young woman. Many mountain men were in love with her.[1][44] Carson was forced to fight a duel with a French trapper named Chouinard for Waanibe's hand in marriage. Carson won, but he had a very narrow escape. The French trapper's bullet singed his hair. The duel was one of the best known stories about Carson in the 19th century.[45]

Carson married Singing Grass. She was a good wife. She tended to his needs, and went with him on his trapping trips. They had a daughter named Adaline (or Adeline). Singing Grass died after giving birth to Carson's second daughter. This child did not live long. In 1843, she fell into a kettle of boiling soap in Taos. Waanibe died about 1841.[1][35]

Carson's life as a mountain man was too hard for a little girl. In 1852, he took Adaline to live with his sister Mary Ann Carson Rubey in Saint Louis, Missouri. Adaline was taught in a school for girls called a seminary.[1] Carson brought her West when she was a teenager. She married and divorced. In 1858, she went to the California goldfields. Adaline died in 1860.[46]

Making-Out-Road[change | change source]

In 1841, Carson married a Cheyenne woman named Making-Out-Road. They were together only a short time. Making-Out-Road divorced him in the way of her people. She put Adaline and all Carson's property outside their tent. Making-Out-Road left Carson to travel with her people through the west.[1] Historian David Lavender writes: "[Making-Out-Road] was spoiled. She had put most of the Cheyenne bachelors and half the white men at the fort in a slow burn, and they had showered her with gifts. Now that they were married she expected Kit to keep her in expensive foofaraw (finery). She ignored her household chores and neglected little Adaline ..."[47]

Josefa Jaramillo[change | change source]

About 1842, Carson met Josefa Jaramillo. She was the beautiful daughter of a wealthy Mexican couple living in Taos. Lewis Garrard wrote: "Her style of beauty was of the haunting, heartbreaking kind ... such as would lead a man with a glance in his eye, to risk his life for one smile."[48] Carson wanted to marry her. He left the Presbyterian Church for the Catholic Church. Thirty-three-year old Carson married 14-year-old Josefa on February 6, 1843. They had eight children.[1]

Travels with Frémont[change | change source]

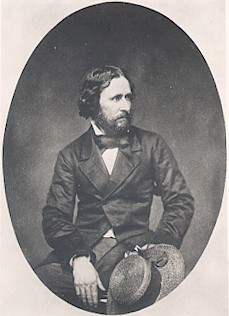

In 1842, Carson was returning from Missouri after depositing his daughter Adaline with relatives when met John Charles Frémont aboard a steamboat on the Missouri River. Frémont was a United States Army officer in the Corps of Topographical Engineers. Carson had very little money at the time and was hired by Frémont at $100 a month as a guide.[1] Frémont wrote, "I was pleased with him and his manner of address at this first meeting. He was a man of medium height, broad-shouldered, and deep-chested, with a clear steady blue eye and frank speech and address; quiet and unassuming."[49]

First expedition, 1842[change | change source]

In 1842, Carson guided Frémont across the Oregon Trail to Wyoming, their first expedition into the West.[6] The purpose of the expedition was to map and describe the Oregon Trail as far as South Pass, Wyoming. A guidebook and maps would be printed for settlers.[50] Frémont praised Carson in his government reports and so Carson became well known across the United States. He became the hero of many cheap popular books called dime novels.[6]

Second expedition, 1843[change | change source]

In 1843, Frémont asked Carson to join his second expedition. Carson guided Frémont across part of the Oregon Trail to the Columbia River in Oregon. The trip's purpose was to map and describe the Oregon Trail from South Pass, Wyoming, to the Columbia River. They also traveled to Great Salt Lake in Utah. The men then headed to California but suffered from bad weather in the Sierra Nevada Mountains. The men were saved by Carson's good judgement and his guiding skills. They found American settlers, who fed them. The expedition then went into California, which was illegal and dangerous. California was Mexican territory. The Mexican government ordered Frémont to leave. He finally went back to Washington, DC. The government liked his reports but ignored his illegal trip into Mexico. Frémont was made a captain, and the newspapers called him "The Pathfinder."[51]

During the expedition, Frémont went to the Mojave Desert. Frémont's party met a Mexican man and boy. The two told Carson that Native Americans had ambushed their party of travelers. The male travelers were killed; the women travelers were staked to the ground, sexually mutilated, and killed. The murderers then stole the Mexicans' 30 horses. Carson and a mountain man friend, Alexis Godey, went after the murderers and took two days to find them. They rushed into their camp and killed and scalped two of the murderers. The stolen horses were recovered and returned to the Mexican man and boy. That selfless and generous deed brought Carson even greater fame. It confirmed his status as a western hero in the eyes of the American people.[52]

Third expedition, 1845[change | change source]

In 1845, Carson guided Frémont on their third and last expedition. They went to California and Oregon.[6] Frémont made scientific plans, but the expedition appeared to be political in nature. Frémont may have been working under secret government orders. President Polk wanted the province of Alta California in the United States. Once in California, Frémont started to rouse the American settlers into a patriotic fever and so tne Mexican government ordered him to leave. Frémont went north to Oregon and camped near Klamath Lake. Messages from Washington, DC, made it clear that President Polk wanted California.

At Klamath Lake in southern Oregon, Frémont's party was attacked by about 20 Native Americans on the night of March 6, 1846. Three men in camp were killed. The Native Americans fled after a brief struggle. Carson was angry that his friends had been killed. He took an axe and avenged the death of his friends by chopping away at a dead Klamath's face. Fremont wrote, "He knocked his head to pieces."[53]

Bear Flag Revolt[change | change source]

In June 1846, both Frémont and Carson participated in a California uprising against Mexico, the Bear Flag Revolt. Mexico ordered all Americans to leave California. They did not want to go and declared California an independent republic. American settlers in California wanted to be free of the Mexican government. The Americans found the courage to oppose Mexico because they had Frémont and his troops on board. He wrote an oath of allegiance. He and his men gave some protection to the Americans. He ordered Carson to execute an old Mexican man named Berresaya and his two adult nephews. The three had been captured when they stepped ashore at San Francisco Bay. They were executed to keep them from taking reports to Mexico about the uprising.[54]

Massacre[change | change source]

Mexico ordered Frémont and Carson to leave the area. They left for Oregon. Along the way, Carson and most of the group attacked a Native American village and killed about 100 villagers. Carson thought that the massacre would discourage Native Americans from attacking white settlers. Frémont heard that the Klamath tribe had killed three of his men. Carson was sorry to have lost his friends. He attacked another Native American village and wrecked it.[7][54]

Frémont worked hard to the win California for the United States and became its military governor. Carson took military records to the Secretary of War in Washington, DC. Frémont wrote, "This was a service of great trust and honor... and great danger also."[1] In 1847 and 1848, Carson made two quick trips to Washington, DC, with messages and reports. In 1848, he took news of the California Gold Strike to the nation's capital.[7]

Books and dime novels[change | change source]

Carson's fame spread throughout the United States with government reports, dime novels, newspaper accounts, and word of mouth. The dime novels celebrated Caron's adventures but were usually colored with exaggeration. A factual biography was attempted by DeWitt C. Peters in 1859 but has been criticized for inaccuracies and exaggerations.

Dime novels[change | change source]

In 1847, the first story about Carson's adventures was printed. Called An Adventure of Kit Carson: A Tale of the Sacramento, it was printed in Holden's Dollar Magazine. Other stories were also printed such as Kit Carson: The Prince of the Goldhunters and The Prairie Flower. Writers thought that Carson the perfect mountain man and Indian fighter. His exciting adventures were printed in the story Kiowa Charley, The White Mustanger; or, Rocky Mountain Kit's Last Scalp Hunt. In it, an older Kit is said to have "had ridden into Sioux camps unattended and alone, had ridden out again, but with the scalps of their greatest warriors at his belt."[55]

Indian captive Mrs. Ann White[change | change source]

In 1849, Carson guided soldiers on the trail of Mrs. Ann White and her baby daughter. They had been captured by Apaches. No one paid attention to Carson's advice about a rescue attempt. Mrs. White was found dead. An arrow was in her heart. She had been horribly abused. She may have been passed among the Apaches as a camp prostitute. Her child had been carried away and was never found.

A soldier in the rescue party wrote: "Mrs. White was a frail, delicate, and very beautiful woman, but having undergone such usage as she suffered nothing but a wreck remained; it was literally covered with blows and scratches. Her countenance even after death indicated a hopeless creature. Over her corpse, we swore vengeance upon her persecutors."[7][56]

Carson discovered a book about himself in the Apache camp. That was the first time that he found himself in print. He was the hero of adventure stories. He was sorry for the rest of his life that Mrs. White had been killed. He wrote in his Memoirs: "In camp was found a book, the first of the kind I had ever seen, in which I was made a great hero, slaying Indians by the hundreds.... I have often thought that Mrs. White read the same... [and prayed] for my appearance that she might be saved."[1]

Memoirs[change | change source]

In 1856, Carson told his life story to someone who wrote it down. Tne book is called Memoirs. Some say Carson forgot dates or got them wrong. The manuscript was lost when it was taken east to find a professional writer who would work it into a book. Washington Irving was asked but declined. The lost manuscript was found in a trunk in Paris in 1905 and was later printed.

The first biography of Carson was written by DeWitt C. Peters in 1859. The book was called Kit Carson, the Nestor of the Mountains, from Facts Narrated by Himself. When it was read to Carson, he said, "Peters laid it on a leetle too thick."[57]

Mexican-American War[change | change source]

The Mexican–American War was between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. Under the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, the defeated Mexico was forced to sell the territories of Alta California and New Mexico to the United States.

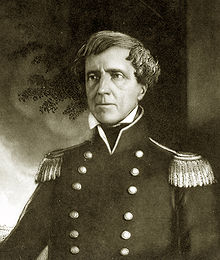

Carson was not a member of the US Army, but one of his best known adventures took place during the war. In December 1846, Carson was ordered by General Stephen W. Kearny to guide him and his troops from Socorro, New Mexico, to San Diego, California. Mexicans soldiers attacked Kearny and his men near the village of San Pasqual, California.[6]

There were too many Mexican soldiers. Kearny knew he would could not win and so he ordered his men to take cover on a small hill. Kearny then sent Carson, a naval lieutenant named Beale, and a Native American scout to get help. The three left on the night of December 8 for San Diego. San Diego was 25 miles (40 km) away. Carson and the lieutenant removed their shoes because they made too much noise. They walked barefoot through the desert.

Carson wrote in his Memoirs: "Finally got through, but had the misfortune to lose our shoes. Had to travel over a country covered with prickly pear and rocks, barefoot."[58] By December 10, Kearny believed that help would not arrive. He planned to break through the Mexican lines the next morning. That night, 200 mounted American soldiers arrived in San Pasqual, swept the area, and drove the Mexicans away. Kearny was in San Diego on December 12.[59] Carson went back to Taos after the Mexican–American War to start a ranch.

Indian agent[change | change source]

In 1853, Carson became the US Indian agent to the Utes, people who lived across northern New Mexico. The Jacarilla Apaches and the Puebloans at the Rio Grande would also come under Carson's watch. His job was to keep the peace between the southwestern tribes and to hunt down and punish any who committed crimes. Carson was honest and fair as an Indian agent.[60]

Carson came to realize that the hostilities between white Americans and Native Americans were the result of a great decrease in available wild game. That situation forced the Native Americans into raiding American farms, ranches, and herds of cattle. He also knew that the liquor available in towns and villages led the Native Americans into serious trouble. Carson wanted the government to put aside large areas of land far from white settlements. The lands would be called reservations and intended for the use of Native Americans only. He thought the Native Americans should be taught agriculture, but it would prove almost impossible to teach nomadic hunters to settle on one piece of land and farm it. He thought his plans would keep these peoples from becoming extinct. Carson resigned as Indian agent with the outbreak of the American Civil War in April 1861. He joined the Union Army to lead the 1st New Mexico Volunteer Infantry.[61][62]

Military life[change | change source]

Civil War[change | change source]

In April 1861, the American Civil War broke out. Carson left his job as an Indian agent and joined the Union Army. He was made a lieutenant and led the 1st New Mexico Volunteer Infantry. He trained the new men. In October 1861, he was made a colonel. The Volunteers fought the Confederate forces at Valverde, New Mexico, in February 1862.[6] The Confederates won that battle but were later defeated.

Campaign against Apaches[change | change source]

Once the Confederates had been driven from New Mexico, Carson's commander, Major James Henry Carleton, turned his attention to the Native Americans. The historian Edwin Sabin wrote that officer had a "psychopathic hatred of the Apaches."[63] Carleton led his forces deep into the Mescalero Apache territory. The Mescaleros were tired of fighting and put themselves under Carson's protection. Carleton put those Apaches on a remote and lonely reservation east on the Pecos River.[64]

Carson disliked the Apaches and wrote in a report that the Jicarilla Apaches "were truly the most degraded and troublesome Indians we have in our department.... [W]e daily witness them in a state of intoxication in our plaza."[65] Carson half-heartedly supported Carleton's plans. He was tired and had suffered an injury two years before that gave him great trouble. He resigned from the Army in February 1863. Carleton refused to accept the resignation because he wanted Carson to lead a campaign against the Navajo.[65]

[change | change source]

Carleton had chosen a bleak site on the Pecos River for his reservation, which was called Bosque Redondo (Round Grove). He chose the site for the Apaches and the Navajos because it was far from white settlements. He also wanted the Apaches and the Navajo to act as a buffer for any aggressive acts committed upon the white settlements from the Kiowas and Comanches to the east of Bosque Redondo. He thought as well that the remoteness and desolation of the reservation would discourage white settlement.[66]

The Mescalero Apaches walked 130 miles to the reservation. By March 1863, 400 Apaches had settled around nearby Fort Sumner. Others had fled west to join fugitive bands of Apaches. By middle summer, many of them were planting crops and doing other farm work.

On July 7, Carson, with little heart for the Navajo roundup, started the campaign against the tribe. His orders were almost the same as those for the Apache roundup: he was to shoot all men on site and to take the women and children captives. No peace treaties were to be made until all of the Navajo were on the reservation.[67]

Carson searched far and wide for the Navajo. He found their homes, fields, animals, and orchards, but the Navajo were experts at disappearing quickly and hiding in their vast lands. The roundup was a great frustration for Carson. In his fifties, he was tired and ill. By autumn 1863, Carson started to burn the Navajo homes and fields and to remove their animals from the area. The Navaho would starve if the destruction continued, and 188 Navajo surrendered. They were sent to Bosque Redondo, where life had turned grim. Murders occurred since the Apaches and Navajos fought. The water in the Pecos contained minerals that gave people cramps and stomach aches. Residents had to walk about twelve miles to find firewood.[68]

Canyon de Chelly[change | change source]

Carson wanted to take a winter break from the campaign, but Carleton refused. Kit was ordered to invade the Canyon de Chelly. It was there that many Navajos had taken refuge. The historian David Roberts wrote, "Carson's sweep through the Canyon de Chelly in the winter of 1863-1864 would prove to be the decisive action in the Campaign."[69]

The Canyon de Chelly was a sacred place for the Navajo. Believing that it would now be their strongest sanctuary, 300 Navajo took refuge on the canyon rim at a place called Fortress Rock. They resisted Carson's invasion by building rope ladders and bridges, lowering water pots into a stream, and keeping out of sight. The 300 Navajo survived the invasion. In January 1864, Carson swept through the 35-mile Canyon with his forces. He cut down the thousands of peach trees in the Canyon. Few Navajo were killed or captured. Carson's invasion, however, proved to the Navajo the white men could invade their country at any time. Many Navajo surrendered at Fort Canby.[70]

By March 1864, there were 3,000 refuges at Fort Canby. An additional 5,000 arrived in the camp. They were suffering from the intense cold and hunger. Carson asked for supplies to feed and clothe them. The thousands of Navajo were led to Bosque Redondo. Many died along the way, and stragglers in the rear were shot and killed. In Navajo history, the horrific trek is known as the Long Walk. By 1866, reports indicated that Bosque Redondo was a complete failure, Carleton was fired, and Congress started investigations. In 1868, a treaty was signed, the Navajo were allowed to return to their homeland, and Bosque Redondo was closed.[71]

First Battle of Adobe Walls[change | change source]

On November 25, 1864, Carson led his forces against the southwestern tribes at the First Battle of Adobe Walls in the Texas Panhandle. Adobe Walls was an abandoned trading post that had been blown up by its inhabitants to prevent a takeover by hostile Native Americans. Combatants at the First Battle were the United States Army and masses of Kiowas, Comanches, and Plains Apaches. It was one of the largest engagements fought on the Great Plains. The Texas State Library and Archives Commission noted: "The result of Adobe Walls was a crushing spiritual defeat for the Indians. It also prompted the U.S. military to take its final actions to crush the Indians once and for all. Within the year, the long war between whites and Indians in Texas would reach its conclusion."[72]

The battle was the result of General Carleton's belief that the Native Americans were responsible for the continuing attacks on white settlers along the Santa Fe Trail. He wanted to punish the thieves and murderers and brought in Carson to do the job. With most of the Army engaged elsewhere during the American Civil War, the protection that the settlers sought was almost nonexistent, and they begged for help. Carson led 260 cavalry, 75 infantry, and 72 Ute and Jicarilla Apache Army scouts. In addition, he had two mountain howitzer cannons.

On the morning of November 25, Carson discovered and attacked a Kiowa village of 176 lodges. After the destruction, he moved forward to Adobe Walls. Carson found other Comanche villages in the area and realized that he would face a very large force of Native Americans. A Captain Pettis estimated that 1,200 to 1,400 Comanche and Kiowa began to assemble. The number would swell to possibly 3,000. Four to five hours of battle ensued. When Carson ran low on ammunition and howitzer shells, he ordered his men to retreat to a nearby Kiowa village, which they burned Along with many fine buffalo robes. His Native American scouts killed and mutilated four elderly and weak Kiowas. Their retreat to New Mexico was then begun. There were few deaths among Carson's men. General Carleton wrote to Carson: "This brilliant affair adds another green leaf to the laurel wreath which you have so nobly won in the service of your country."[1] The battle is considered by some to be Carson's finest moment and is thought to be one of the factors that made the Kiowas and the Comanches sue for peace in 1865.[73]

"Throw a few shells into that crowd over there."

Some of those who have studied the battle believe that Carson was correct in ordering his troops to retreat. Only one Comanche scalp was reported to ne taken by Carson's soldiers. The First Battle at Adobe Walls would be the last time the Comanche and Kiowa forced American troops to retreat from battle. Adobe Walls marked the beginning of the end of the Plains tribes and of their way of life.

A decade later, the Second Battle of Adobe Walls was fought on June 27, 1874, between 250 and 700 Comanche and a group of 28 hunters defending Adobe Walls. After a four-day siege, the hundreds of Native Americans withdrew. The Second Battle led to the Red River War of 1874–1875, which that resulted in the final relocation of the Southern Plains Indians to reservations in Oklahoma.

Death[change | change source]

Carson left the army on November 22, 1867. He moved his family to a small settlement on the Purgatoire River called Boggsville, Colorado. He had no money and sold his house in Taos. He wanted to build a ranch.[1] In January 1868, he was made superintendent of Indian Affairs in the Colorado Territory. He was called to Washington, DC, in February 1868 with Ute chiefs and other men to make a treaty. Carson was seriously ill and doubted that he could make the journey, but he felt a responsibility to the chiefs and made the journey. He asked doctors on the East Coast about his health (they gave him little hope of recovery) and toured New York City, Philadelphia, and Boston. His last photograph was snapped in Boston.[1]

He returned home in April 1868. Josefa had given birth to their last child, Josefita. It was not an easy birth, and Josefa died within two weeks on April 23, 1868. Carson missed her greatly. His health grew worse. He needed chloroform to ease the pain. Carson made his will on May 15, 1868 at Fort Lyon and named Thomas Boggs his administrator. Any monies realized from his estate would be used to support his children. Carson had been diagnosed with an aortic aneurysm. The aneurysm broke; Carson's mouth gushed with blood. His doctor and his best friend Thomas Boggs were present when he died. Carson's last words were "Doctor, goodbye. Compadre, adíos." He died on May 23, 1868 at Fort Lyon, Colorado. He was 58 years old.

The wife of an officer offered her wedding dress to line Carson's casket, and the women of the fort took the cloth flowers from their hats to decorate his coffin. Carson and Josefa were first buried in Boggsville. Both were disinterred in 1869 and buried in Taos, New Mexico.[75]

Legacy[change | change source]

Carson's home in Taos is today a museum maintained by the Kit Carson Foundation. A monument was raised in the plaza at Santa Fe by the New Mexico Grand Army. In Denver, a statue of a mounted Kit Carson can be found atop the Mac Monnies Pioneer Monument. Another equestrian statue can be seen in Trindad. A national forest in New Mexico was named for Carson as well as a mountain and a county in Colorado. A river in Nevada is named for Carson as well as the state's capital, Carson City. Fort Carson, an army training post near Colorado Springs, was named for him during World War II by popular vote of the men training there.[76]

In the 1960s and the 1970s, Carson came under the scrutiny of revisionist historians. He had been regarded as an American hero, but as the tide turned, he became an archvillain in the genocidal campaign against the Native Americans. Clifford Trafzer's 1982 Kit Carson Campaign: The Last Great Navajo War found fault with both Carleton and Carson, but Trafzer completely ignored Carson's many acts and deeds that humanized the Long Walk.

In 1992, a young professor at Colorado College was successful in abruptly demanding for a period photograph of Carson to be removed from the ROTC office. That year, a tourist told a journalist at the Carson home in Taos, "I will not go into the home of that racist, genocidal killer." In 1973, militants in Taos tried to change the name of Kit Carson State Park. Six years later, Kit Carson Cave near Gallup, New Mexico, was the target of vandals, and in 1990, protestors spraypainted Kit and Josefa's tombstones with the word "NAZI". In the 1970s, a Navajo at a trading post said, "No one here will talk about Kit Carson. He was a butcher." In 1993, a symposium was organized to air various views on Carson, but the Navajo spokespeople refused to attend.[77]

In time, views of Carson returned to their former glory. David Roberts wrote, "Carson's trajectory, over three and a half decades, from thoughtless killer of Apaches and Blackfeet to defender and champion of the Utes, marks him out as one of the few frontiersmen whose change of heart toward the Indians, born not of missionary theory but of first hand experience, can serve as an exemplar for the more enlightened policies that sporadically gained the day in the twentieth century."[78]

Footnotes[change | change source]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 Kit Carson

- ↑ Roberts 187

- ↑ Sides 50-51

- ↑ Roberts 186

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Roberts 55

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 World Book 250-251

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 Volpe

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Roberts 54

- ↑ Guild 3

- ↑ Sides 8

- ↑ Sides 9

- ↑ Guild 9

- ↑ Roberts 54-55

- ↑ Sides 8-9

- ↑ Guild 10

- ↑ Guild 15

- ↑ Guild 27

- ↑ Roberts 56-57

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Roberts 56

- ↑ Sides 14

- ↑ Guild 26

- ↑ Guild 32

- ↑ Guild 48

- ↑ Cleland 44

- ↑ Cleland 40-41

- ↑ Cleland 37

- ↑ Cleland 30

- ↑ Cleland 21

- ↑ Cleland 43

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Roberts 80

- ↑ Sides 15

- ↑ Roberts 66

- ↑ Sides 29

- ↑ Sides 34

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Roberts 98

- ↑ Sides 33-34

- ↑ Roberts 99-101

- ↑ Sides 16

- ↑ Roberts 79-80

- ↑ Roberts 82

- ↑ Roberts 85

- ↑ Roberts 87-88

- ↑ Roberts 71

- ↑ Sides 29-30

- ↑ Roberts 70

- ↑ Roberts 101-102

- ↑ Roberts 100

- ↑ Roberts 124

- ↑ Roberts 103

- ↑ Sides 51-52

- ↑ Sides 59-61

- ↑ Sides 62-64

- ↑ Sides 78-81

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 Brief history

- ↑ Roberts 52, 79

- ↑ Sides 258-259

- ↑ Roberts 253-254

- ↑ Sides 163

- ↑ Sides 164-165

- ↑ Roberts 251

- ↑ Kit Carson Biography

- ↑ Roberts 252, 254

- ↑ Roberts 255

- ↑ Roberts 257

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 Roberts 258

- ↑ Roberts 259

- ↑ Roberts 260

- ↑ Roberts 262

- ↑ Roberts 263

- ↑ Roberts 265-269

- ↑ Roberts 270-281

- ↑ The Battle of Adobe Walls | TSLAC Texas State Library and Archives Commission: The Battle of Adobe Walls

- ↑ Guild 255

- ↑ Fort Tours|Adobe Walls

- ↑ Guild 276-284

- ↑ Guild 283-284

- ↑ Roberts 292-295

- ↑ Roberts 294

References[change | change source]

- A Brief History of the Bear Flag Revolt Archived 2013-11-27 at the Wayback Machine

- Cleland, Robert Glass. 1963. This Reckless Breed of Men. Knopf.

- Kit Carson Biography

- Guild, Thelma S., and Harvey L. Carter. 1984. Kit Carson: a pattern for heroes. University of Nebraska Press.

- "Kit Carson: the legendary frontiersman remains an American hero". Published by Wild West

- Roberts, David. 2000. A Newer World: Kit Carson, John C. Fremont, and the claiming of the West. Simon & Schuster.

- Sides, Hampton. 2006. Blood and Thunder: an epic of the American West. Doubleday.

- Volpe, Vernon. 2013. "Kit Carson". Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia.

- World Book Encyclopedia. Volume 3. 2012. Scott, Foresman.