Armenians in Turkey

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 50,000–70,000[1][2] (excluding Crypto-Armenians) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Istanbul, Diyarbakır, Kars, Vakıflı, and Iskenderun | |

| Languages | |

| Turkish (majority), Western Armenian (minority)[3][4] | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Armenian Apostolic with Armenian Catholic, Armenian Evangelical, and Muslim minorities. |

Armenians in Turkey (Turkish: Türkiye Ermenileri; Armenian: Հայերը Թուրքիայում, romanized: Hayery T’urk’iayum; "Turkish Armenians"), are ethnic Armenians living in Turkey.

They have an estimated population of 50,000 to 70,000,[1] down from a population of over 2 million Armenians between the years 1914 and 1921. Until the Armenian genocide of 1915, most of the Armenian population of Turkey lived in the eastern parts of the country that Armenians call Western Armenia. Today, the overwhelming majority of Turkish Armenians are concentrated in Istanbul.

They support their own newspapers, churches and schools, and the majority belong to the Armenian Apostolic Church and a minority of Armenians in Turkey belong to the Armenian Catholic Church or to the Armenian Evangelical Church.

Geographical distribution[change | change source]

Istanbul[change | change source]

Of the 60,000 Christian Armenians living in Turkey, 45,000 live in Istanbul.[5] Today, in the Kumkapı quarter in Fatih, Istanbul, the various churches Armenian, Greek Orthodox and Syriac as well as the Armenian Patriarchate of Turkey. In some ways, the quarter has even regained its reputation as an Armenian quarter. Yet, the majority of Armenians residing in Kumkapı today are immigrants from Armenia, while of the original Armenian population, only a few individuals still call Kumkapı their home.[6] The Armenian population in Turkey, which makes up the largest Christian community in the country, "resembles an iceberg melting in the sea" with its some 60,000 members, the newly elected Armenian Apostolic Patriarch of Istanbul has said.[7] At present, the Armenian community in Istanbul has 20 schools (including the Getronagan Armenian High School), 17 cultural and social organizations, three newspapers (Agos, Jamanak, Marmara), two sports clubs (Şişlispor, Taksimspor).

Dersim[change | change source]

According to Mihran Prgiç Gültekin, the head of the Union of Dersim Armenians, around 75% of the population in villages of Dersim are "converted Armenians."[8][9] The greater part of hidden Armenians of Dersim, according Gultekin, is afraid that the nationalist regime may be back and may repress them. Currently over 200 families have announce their Armenian descent in Dersim, Gultekin said.[10] In April 2013, Aram Ateşyan, the acting Armenian Patriarch of Istanbul, stated maybe that 90% of Tunceli (Dersim)'s population is of Armenian origin.[11] In 2015, a group of citizens in Dersim (Tunceli) established the Dersim Armenians and Alevis Friendship Association (DERADOST). The opening ceremony of the association was attended by Hüseyin Tunç, then Deputy Mayor of Tunceli, Yusuf Cengiz, President of Tunceli Chamber of Commerce and Industry, representatives of non-governmental organisations and some citizens.[12][13] On the 100th anniversary of the Armenian Genocide, president of the association Serkan Sariataş said that the state should face its past history as soon as possible.[14] In 2015, 12 crypto-Armenians from Dersim baptized in Istanbul.[15] The districts of Mazgirt, Nazımiye and Çemişgezek had a large Armenian population during the Ottoman period. A large part of this population must have been deported out of Anatolia with the deportation order of 1915. It is likely that the remaining population migrated to Western Anatolia.[16] Through the 20th century, an many of Armenians living in the mountainous region of Dersim had converted to Alevism. During the Armenian genocide, many of the Armenians in the region were saved by their Kurdish neighbors.

Muş[change | change source]

| Armenian population in Muş Sanjak, 1914 | % Armenian | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Kaza | Total population[17] | Armenian population[18] | |

| Muş | 66,570 | 35,786 | 53.75% |

| Bulanık | 31,034 | 14,662 | 47.24% |

| Sasun | 13,959 | 6,505 | 46.60% |

| Malazgirt | 35,367 | 4,438 | 12.54% |

| Varto | 16,529 | 1,990 | 12.03% |

| Muş Sanjak | 163,459 | 60,682 | 37.12% |

In 2014, Armenians from Muş established an association. Daron Moush Armenians Solidarity Social Tourism Association made an official application after the formation of a board of seven members. The association, which started its activities in Muş and started accepting members, elected its president next week.[19] Speaking at the foundation ceremony of the Daron Muş Armenians Solidarity, Social and Tourism Association, board member Armen Galustyan said, "Regardless of religion, Armenianism is a race, a nation, just like the Turks, Kurds and Arabs. Armenianhood is not an enmity."[20][21]

Hatay[change | change source]

Vakıflı, located in the Samandağ district of Hatay province of Turkey, is the only Armenian village in Turkey with a population of 100 people, all of whom are Armenians. The entire village population is Armenian.[22]

Rize[change | change source]

The Hemshin people, also known as Hemshinli or Hamshenis or Homshetsi,[23][24][25] are an numerically small group of Sunni Muslim Armenians who had been converted from Christianity in the beginning of the 18th century[26] who are affiliated with the Hemşin and Çamlıhemşin districts in the province of Rize, Turkey.[27][28][29][30] They are Armenian in origin, and were originally Christian and members of the Armenian Apostolic Church, but over the centuries evolved into a distinct ethnic group and converted to Sunni Islam after the conquest of the Ottomans of the region during the second half of the 15th century.[31]

Batman[change | change source]

Sason

An Armenian minority may still live in Sason (according to an estimate which was made in 1972, about 6,000 Armenian villagers were still living in the region).[32]

Culture[change | change source]

Language[change | change source]

Most Armenians in Turkey speak Turkish, not Armenian, and this rate rises to 92 percent among young people.[33] On 21 February 2009, International Mother Language Day, a new edition of the Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger was released by UNESCO in which the [Western] Armenian language in Turkey was defined as a definitely endangered language, Also, Hamsheni, a branch of Western Armenian, was classified separately language.[34][35] Some Muslim Hamshenis, influenced by the fact that the Homshetsi dialect of Armenian is preserved as the spoken language in their circles, accept the fact that they are of Armenian origin. However, Hamshenis in Rize have mostly forgotten their mother tongue and they speak Turkish.[36]

The Armenian-speaking population in Turkey according to censuses

| Year | Total Armenian speakers[37] | % | Note | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L1[37] | L2[37] | |||

| 1927 | 67,745 | 0.50% | 67,745 | –

|

| 1935 | 67,381 | 0.42% | 57,599 | 9,782 |

| 1945 | 60,082 | 0.32% | 47,728 | 12,354 |

| 1950 | 62,098 | 0.30% | 52,776 | 9,322 |

| 1955 | 62,319 | 0.26% | 56,235 | 6,084 |

| 1960 | 72,200 | 0.26% | 52,756 | 19,444 |

| 1965 | 55,354 | 0.18% | 33,094 | 22,260 |

Music[change | change source]

Music culture especially developed among the Hamshenis. The first music album made by Homshetsi dialect is Vova, which consists of anonymous folk music.[38][39] The national Hamsheni instruments include tulum, şimşir kaval or the Hamshna-Zurna. Komitas, Rober Hatemo, Hayko Cepkin, Yaşar Kurt, Cem Karaca (half-Armenian), Udi Hrant Kenkulian can be given as an example to many Armenians working on Turkish and Armenian music.

Cinema and acting[change | change source]

In movie acting, special mention should be made of Vahi Öz who appeared in countless movies from the 1940s until the late 1960s, Sami Hazinses (real name Samuel Agop Uluçyan) who appeared in tens of Turkish movies from the 1950s until the 1990s and Nubar Terziyan who appeared in more than 400 movies. Movie actor and director Kenan Pars (real name Kirkor Cezveciyan) and theatre and film actress Irma Felekyan (aka Toto Karaca), who was mother of Cem Karaca.

Assimilation and Armenian place names[change | change source]

Although the Armenian place names in Turkey are mostly changed, some names are used officially today.

It estimated that 3,600 Armenian geographical locations have been changed and changed Armenian place names make up 8.8% of place names in Turkey.[41]

Some province, district and place names of Armenian origin

Rize

- Ardeşen, from Armenian Ardaşén means "fieldvillage".

- Hemşin, from Armenian Hamamaşén/Hamşén means "Hamam's village". Çamlıhemşin is a combination of the Turkish word Çamlı and the Armenian word.

Diyarbakır

- Çermik, from Armenian Çermuk means "spa" .

Elâzığ

- Keban, from Armenian Gaban means "passage".

Ağrı

- Patnos, from Armenian Patnots maybe means "surrounded" or "fenced".

Muş

- Varto, it was recorded in 1554 as Varto kavar, which means "Vart's district" in Armenian. Varto is probably related to the Armenian personal name Vartan.

- Malazgirt, from Armenian Manavazagerd/Manazgerd means "Manavaz's fortress".

Şanlıurfa

- Siverek, from Armenian Seraverag means "black ruins".

Tunceli

- Pertek, from Armenian Pertag means "small castle".

- Mazgirt, from Armenian Medzgerd means "great fortress".

Malatya

- Arguvan, from Armenian Arkavan means "king's city/village".

Province names of Armenian origin

- Erzincan, from Armenian Erizagan means "Belonging to Erez", "from Erez".

- Bayburt, from Armenian Baberd, berd means "castle", but the structure of the compound is doubtful.

Demographics[change | change source]

On the eve of the World War I there were estimated between 1,500,000 and 2,000,000 Armenians in the Ottoman Empire[42][43] however, according to the 1914 Ottoman census, this figure is only 1,229,007, of which 1,161,169 "Armenians" and 67,838 "Armenian Catholics".[44] Estimates of the Armenian population in Turkey today range from 50,000 to 70,000,[1][5][2] but these number not include secret and Islamized Armenians, with population estimates ranging from 80,000 to 300,000.[45][1][5][2] In 1987, Suren Eremian on Armenian Soviet Encyclopedia says 180,000 Armenians live in Turkey with more than forcibly 1,000,000 "Muslimized" Armenians.[46] Keith David Watenpaugh says about this:

Two million contemporary Turks may have at least one Armenian grandparent, although the costs of revealing Armenian ancestry in public are potentially so high as to preclude the possibility of arriving at an accurate number.[47]

Armenian population in Ottoman Empire according to censuses[change | change source]

| Year | Total population | % | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1881/82–1893[48] | 1,001,465 | 5.75% | 1,001,465 "Armenians" of 463,011 female and 538,454 male, not including Armenian Catholics. |

| 1906/7[49] | 1,120,748 | 5.36% | 1,031,708 "Armenians" of 547,526 male and 484,182 female, 89,040 "Armenian Catholics" of 47,991 male and 41,049 female. |

| 1914[44] | 1,229,007 | 6.63% | 1,161,169 "Armenians", 67,838 "Armenian Catholics". |

1914 census by vilayets[change | change source]

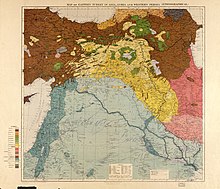

Armenians were found especially in the east of the Ottoman Empire, there were significant Armenian diasporas in Western Anatolia.

| Vilayet | Armenian population[44] | % |

|---|---|---|

| Bitlis | 117,492 | 26.85% |

| Van | 67,792 | 26.16% |

| Erzurum | 134,377 | 16.47% |

| Mamuret-ul-Aziz | 79,821 | 14.83% |

| Adana | 52,650 | 12.80% |

| Sivas | 147,099 | 12.57% |

| Diyarbekir | 65,850 | 10.62% |

| Hüdâvendigar | 60,199 | 9,76% |

| Constantinople | 82,880 | 9.10% |

| Angora | 51,576 | 5.40% |

| Trabzon | 38,899 | 3.46% |

| Adrianople | 19,773 | 3.13% |

| Konya | 12,971 | 1.64% |

| Aydın | 20,287 | 1.26% |

| Kastamonu | 8,959 | 1.16% |

| Other | 271,382 | |

| 1,229,007 | 6.63% |

1906/7 census by vilayets[change | change source]

| Vilayet | Armenian population[49] | % |

|---|---|---|

| Van | 64,108 | 39.63% |

| Bitlis | 95,393 | 32.04% |

| Erzurum | 116,180 | 17.19% |

| Mamuret-ul-Aziz | 67,522 | 14.26% |

| Diyarbekir | 52,013 | 13.24% |

| Sivas | 147,356 | 12,33% |

| Adana | 50,340 | 9.98% |

| Angora | 97,920 | 8.46% |

| Hüdâvendigar | 80,153 | 4.73% |

| Trabzon | 51,483 | 3.83% |

| Aydın | 19,045 | 1.10% |

| Other | 279,235 | |

| 1,120,748 | 5.36% |

Notable people[change | change source]

List of Armenians born or originating in Turkey and the Ottoman Empire

The persons on the list are classified into three separate categories:

- Christian Armenian

- Muslim Armenian

- Hamsheni (also Muslim Armenians)

Politicians[change | change source]

- Hagop Kazazian Pasha (1836–1891) Christian Armenian, minister of finance and privy treasury in Ottoman Empire

- Gabriel Noradunkyan (1852–1936) Christian Armenian, minister of trade and foreign affairs in Ottoman Empire

- Armen Garo (1872–1923) Christian Armenian, activist and politician, was leading member of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation for more than two decades

- Mesut Yılmaz (1947–2020) Hamsheni, politician who served in ministerial positions such as the prime minister, minister of culture and tourism, the minister of state and deputy prime minister

- Mekertich Portukalian (1848–1921) Christian Armenian, liberal politician, teacher and journalist founder of Armenakan Party

- Garo Paylan (b. 1972) Christian Armenian, politician and member of parliament

- Murat Karayalçın (b. 1943) Hamsheni, politician who served as minister of foreign affairs, deputy prime minister, mayor of Ankara and the founder of the SHP

- Selina Özuzun Doğan (b. 1977) Christian Armenian, politician and member of parliament

- Alper Taş (b. 1967) Hamsheni, socialist politician and former leader of Left Party

- Markar Esayan (1969–2020) half Christian Armenian, politician and member of parliament

- Krikor Zohrab (1861–1915) Christian Armenian, politician, influential writer and lawyer

Popular culture[change | change source]

- Diran Kelekian (1862–1915) Christian Armenian, journalist and professor

- Khachatur Malumian (1863–1915) Christian Armenian, journalist and political activist

- Bîmen Dergazaryan (1873–1943) Christian Armenian, composer and lyricist

- Komitas Vardapet (1869–1935) Christian Armenian, priest, musicologist, composer, arranger, singer and choirmaster who is considered the founder of the Armenian national school of music

- Rupen Zartarian (1874–1915) Christian Armenian, writer, educator and political activist

- Bedros Keresteciyan (1840–1909) Christian Armenian, journalist, translator, and writer of the first etymology dictionary of the Turkish language

- Daniel Varoujan (1884–1915) Christian Armenian, notable poet

- Yervant Odian (1869–1926) Christian Armenian, satirist, journalist and playwright

- Krikor Torosian (1884–1915) Christian Armenian, satirical writer, journalist and publisher

- Güllü Agop (1840–1902) Christian Armenian, actor, founder of modern Turkish theatre

- Armen Dorian (1892–1915) Christian Armenian, poet, teacher and editor

- Ruben Sevak (1886–1915) Christian Armenian, poet, prose-writer and doctor

- Hagop Baronian (1843–1891) Christian Armenian, writer, playwright, journalist and educator

- Rober Hatemo (b. 1974) Christian Armenian, singer

- Özcan Alper (b. 1975) Hamsheni, director and screenwriter

- Şahan Arzruni (b. 1943) Christian Armenian, pianist

- Zahrad (1924–2007) Christian Armenian, promient poet

- Hrant Dink (1954–2007) Christian Armenian, former editor of the weekly Agos

- Ruhi Su (1912–1985) Muslim Armenian, opera singer, folk singer and saz virtuoso

- Nubar Terziyan (1909–1994) Christian Armenian, promient actor

- Adile Naşit (1930–1987) actress, partial Christian Armenian descent

- Hayko Cepkin (b. 1978) Christian Armenian, musician

- Ara Güler (1928–2018) Christian Armenian, journalist, photojournalist and writer

- Aydoğan Topal (b. 1982) half Hamsheni, singer

- Sami Hazinses (1925–2002) Christian Armenian, film actor, composer and lyricist

- Cem Karaca (1945–2004) half Christian Armenian, rock musician

- Kamer Sadık (1911–1986) Christian Armenian, cinema actor

- Behçet Gülas (b. 1975) Hamsheni, musician and singer

- Danyal Topatan (1916–1975) Christian Armenian, theater and television actor

- Fedon (b. 1946) half Christian Armenian, singer, tavern music commentator

- Jaklin Çarkçı (b. 1958) Christian Armenian, mezzo-soprano

- Masis Aram Gözbek (b. 1987) Christian Armenian, conductor of Bosphorus Jazz Choir

- Sevan Nişanyan (b. 1956) writer and linguist, an atheist but Christian Armenian origin

- Kenan Pars (1920–2008) Christian Armenian, promient actor

Armenian fedayis and millitary leaders[change | change source]

- Hampartsoum Boyadjian (1860–1915) Christian Armenian, Hunchakian fedayi

- Arabo (1863–1893) Christian Armenian, Dashnak fedayi

- Armenak Yekarian (1870–1926) Christian Armenian, Armenakan fedayi

- Kevork Chavush (1870–1907) Christian Armenian, Dashnak fedayi

- Sebastatsi Murad (1874—1918) Christian Armenian, Hunchakian fedayi

- Andranik Ozanian (1865–1927) Christian Armenian, Dashnak fedayi, national hero

Other millitary

- Cihan Alptekin (1947–1972) Hamsheni, militant, revolutionary, political activist who was leader of left-wing organisations such as People's Liberation Army of Turkey and Revolutionary Youth Federation of Turkey

- Sarkis Torosyan (1891–1954) Christian Armenian, captain who awarded with a medal by Enver Pasha, however, later changed sides and joined the struggle against the Ottomans

Other[change | change source]

- Daron Acemoglu (b. 1967) Christian Armenian, economist, winner of the 2005 John Bates Clark Medal

- Calouste Gulbenkian (1869–1955) Christian Armenian, businessman and philanthropist who was born in Üsküdar, Istanbul

References[change | change source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Turay, Anna. "Tarihte Ermeniler". Bolsohays: Istanbul Armenians. Archived from the original on 6 December 2006. Retrieved 2007-01-04.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Khojoyan, Sara (16 October 2009). "Armenian in Istanbul: Diaspora in Turkey welcomes the setting of relations and waits more steps from both countries". ArmeniaNow.com. Archived from the original on 1 January 2017. Retrieved 5 January 2013.

- ↑ Helix Consulting LLC. "Turkologist Ruben Melkonyan publishes book "Review of Istanbul's Armenian community history"". Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ↑ UNESCO Culture Sector, UNESCO Interactive Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger, 2009 Archived February 22, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 "Foreign Ministry: 89,000 minorities live in Turkey". Today's Zaman. "The Foreign Ministry has prepared a report identifying the number of minorities living in Turkey and their houses of worship. According to the report, Turkey hosts 89,000 minorities, including 60,000 Armenians, 25,000 Jews and 3,000 to 4,000 Greeks. Containing detailed statistics about the minority groups in Turkey, the report reveals that 45,000 of approximately 60,000 Armenians reside in İstanbul."

- ↑ "Managing the difficult balance between tourism and authenticity: Kumkapı". Hürriyet Daily News. "Today, the various churches Armenian, Greek Orthodox and Syriac as well as the Armenian Patriarchate of Turkey, which are situated in Kumkapı, immediately remind the visitor of this multi-ethnic past. In some ways, the quarter has even regained its reputation as an Armenian quarter. Yet, the majority of Armenians residing in Kumkapı today are immigrants from Armenia, while of the original Armenian population, only a few individuals still call Kumkapı their home."

- ↑ "Armenian population of Turkey dwindling rapidly: Patriarch". Hürriyet Daily News. "The Armenian population in Turkey, which makes up the largest Christian community in the country, “resembles an iceberg melting in the sea” with its some 60,000 members, the newly elected Armenian Apostolic Patriarch of Istanbul has said."

- ↑ "Mihran Gultekin: Dersim Armenians Re-Discovering Their Ancestral Roots". Massis Post. "75 percent of Dersim population is converted Armenians, founder of “Union of Dersim Armenians” Mihran Gultekin told reporters in Yerevan (Dersim is a region of eastern Turkey, which includes Tunceli Province, Elazig Province, and Bingöl Province)."

- ↑ "Documentary on Islamized Armenians of Dersim Screened at Columbia University". Armenian Weekly. "Mihran Prgiç Gültekin, the head of the Union of Dersim Armenians, estimates that about 75% of the village’s population are “converted Armenians."

- ↑ "Mihran Gultekin: Dersim Armenians Re-Discovering Their Ancestral Roots". Massis Post. "The greater part of hidden Armenians of Dersim, according Gultekin, is afraid that the nationalist regime may be back and may repress them. Currently over 200 families have announce their Armenian descent in Dersim, Gultekin said."

- ↑ "Tunceli'nin yüzde 90'ı dönme Ermeni'dir". İnternet Haber. "Erkam Tufan, “Tunceli civarında çok fazla sayıda Kripto Ermeni olduğu söyleniyor bu doğru mudur?” şeklindeki sorusuna Ateşyan şu yanıtı verdi: [...] “Doğrudur Tunceli'nin yüzde 90'ı belki dönme Ermeni'dir. Neden derseniz 30 yaşlarında bir çocuk geldi bana ve ''benim köküm Ermeni'' dedi. ''Ben dönmek istiyorum'' dedi. Ben de ''ispatla dedim'' ispatlayamadı, kabul etmedim. Ama inatla gitti geldi, vazgeçmedi. Gitti, geldi rahatsız etti beni, daha sonra babası aradı. Beyefendi dedi ''ben belediye çalışıyorum emekli olayım bende İstanbul'a gelip döneceğim. Buradaki halkın yüzde 90'ı Ermeni'dir, lütfen kabul et'' dedi. Bende kabul ettim ders aldı, vaftiz oldu, kilisemizin üyesi oldu.”"

- ↑ "Tunceli'de Ermeni ve Alevi dostluk derneği kurdu". Hürriyet. "Tunceli'de bir grup vatandaş, Dersimli Ermeniler ve Aleviler Dostluk Derneği (DERADOST) kurdu. Moğultay Mahallesi Ata Sokak’taki bir iş hanında kurulan derneğin açılışına Tunceli Belediye Başkan Yardımcısı Hüseyin Tunç, Tunceli Ticaret ve Sanayi Odası Başkanı Yusuf Cengiz, sivil toplum kuruluşu temsilcileri ile bazı vatandaşlar katıldı."

- ↑ "Tunceli'de Ermeni ve Alevi Dostluk Derneği Kurdu". Haberler. "Tunceli'de bir grup vatandaş, Dersimli Ermeniler ve Aleviler Dostluk Derneği (DERADOST) kurdu. Moğultay Mahallesi Ata Sokak'taki bir iş hanında kurulan derneğin açılışına Tunceli Belediye Başkan Yardımcısı Hüseyin Tunç, Tunceli Ticaret ve Sanayi Odası Başkanı Yusuf Cengiz, sivil toplum kuruluşu temsilcileri ile bazı vatandaşlar katıldı."

- ↑ "DERADOST başkanından Erdoğan ile Davutoğlu'na Ermeni Soykırımı çağrısı". Ermeni Haber Ajansı. "Ermeni Soykırımı'nın 100. yılında Dersimli Ermeniler ve Aleviler Dostluk Derneği (DERADOST) Başkanı Serkan Sariataş, devletin bir an önce geçmiş tarihiyle yüzleşmesi gerektiğini söyledi."

- ↑ "12 crypto-Armenians from Dersim baptized in Istanbul". Hürriyet Daily News. "Twelve Armenians from Dersim, an older name of the eastern Turkish province of Tunceli, were baptized in an Armenian church in Istanbul on May 9, daily Agos has reported."

- ↑ Sertel (2016), p. 8.

- ↑ Karpat (1985), p. 175, Ottoman Population, 1914 (continued).

- ↑ Karpat (1985), p. 174, Ottoman Population, 1914 (continued).

- ↑ "Muş Ermenileri derneklerine kavuştu". Agos. "Sasonlular, Sivaslılar, Malatyalılar ve Dersimlilerden sonra Muşlu Ermeniler de bir dernek kurdu. Daron Muş Ermenileri Dayanışma Sosyal Turizm Derneği, yedi kişilik yönetim kurulunun oluşmasının ardından resmi başvuruda bulundu. Muş’ta faaliyetlerine ve üye kabul etmeye başlayan dernek, önümüzdeki hafta başkanını seçecek."

- ↑ "Muş'ta Ermeni derneği açıldı". Hürriyet. "Muş’ta Daron Muş Ermeniler Dayanışma, Sosyal ve Turizm Derneği’nin kuruluş töreninde konuşan yönetim kurulu üyesi Armen Galustyan, “Dini ne olursa olsun Ermenilik de Türk gibi, Kürt gibi, Arap gibi bir ırktır, bir millettir. Ermenilik bir düşmanlık değildir” dedi."

- ↑ "Muş'ta Ermeni derneği açıldı". Haberler. "Muş’ta Daron Muş Ermeniler Dayanışma, Sosyal ve Turizm Derneği’nin kuruluş töreninde konuşan yönetim kurulu üyesi Armen Galustyan, “Dini ne olursa olsun Ermenilik de Türk gibi, Kürt gibi, Arap gibi bir ırktır, bir millettir. Ermenilik bir düşmanlık değildir” dedi."

- ↑ "Türkiye'deki tek Ermeni köyü: Vakıflı". Ermeni Haber Ajansı. "Türkiye'nin Hatay ilinin Samandağ ilçesinde bulunan ve 160 kişilik nüfusunun tamamı Ermenilerden oluşan Vakıflı, Türkiye'deki tek Ermeni köyü. [...] Köyü, diğer köylerden ayıran nokta ise köy ahalisinin tamamının Ermenilerden oluşması."

- ↑ Vaux (2001), p. 1.

- ↑ Simonian (2007).

- ↑ Dubin & Lucas (1989), p. 126.

- ↑ Wixman (2012).

- ↑ Vaux (2001), pp. 1–2, 4–5.

- ↑ Andrews (1989), pp. 476–477, 483–485, 491.

- ↑ Simonian (2007a), p. 80.

- ↑ Hachikian (2007), pp. 146–147.

- ↑ Simonian (2007), p. xx, Preface.

- ↑ Hewsen (2001), p. 268.

- ↑ "Turkologist Ruben Melkonyan publishes book “Review of Istanbul’s Armenian community history”". Panorama. "According to Melkonyan, Turkey’s Armenian community faces educational problem; the number of Armenian schools decreases year by year. This number has fallen from 47 to 16 with 3000 Armenian students. The expert said that only 18 percent of Armenian community speaks Armenian, the rest Armenians are Turkish-speaking. 92 percent young people is Turkish-speaking."

- ↑ "UNESCO: Türkiye'de 15 Dil Tehlikede". Bianet. "Kesinlikle tehlikede olanlar: Abazaca, Hemşince, Lazca, Pontus Yunancası, Çingene dilleri (Atlasta yalnızca Romani bulunuyor), Süryanice'ye benzeyen Suret (atlasa göre Türkiye'de konuşan kalmadı; konuşanların çoğu göçle başka ülkelere gitti) ve Ermenice."

- ↑ "Dünya nüfusunun yüzde 40'ı ana dilinde eğitimden yoksun: Türkiye'de 15 dil yok oluyor". Euronews. "Açıkça tehlikede: Abazaca, Hemşince, Lazca, Pontus Yunancası, Çingene dilleri, Süryaniceye benzeyen Suret, Batı Ermenicesi".

- ↑ "Kimdir Bu Hemşinliler?". Bianet. "Söz konusu ilçelerdeki Hemşinlilerin bir bölümü, çevrelerinde konuşma dili olarak Ermenice’nin Hamşen lehçesinin korunuyor olmasından etkilenerek, Ermeni kökenli oldukları gerçeğini kabulleniyor. Bu kabullenişin kaynağında, Hopa ve Borçka ilçelerinde Hemşinliler arasında Marksist ve ateist fikirlerin yaygın olması, Türk İslam etkisine karşı yerel kültürünü savunma işlevi de gördüğünü düşünüyorum. [...] Hopalı Hemşinliler’den farklı olarak, ana dilini unutarak Türkçeyi benimseyen Rizeli Hemşinliler için durum tamamen farklı. Çünkü burada Türkleşmenin izleri çok daha derin."

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 Dündar (2000), p. 91.

- ↑ "Alt kimlik dertleri yok alt tarafı müzik yapıyorlar". Zaman Pazar. "Türkiyede ve dünyada ilk Hemşince albüm olma özelliği taşıyan Vova, Ada Müzikin başarılı bir çalışması."

- ↑ "Damardan Hemşin Ezgileri: VOVA". NTV Türkçe. "Dünyadaki, tamamı anonim Hemşin ezgilerinden oluşan ve Hemşince söylenmiş ilk müzik albümü olan ‘Vova’da, Hikmet Akçiçek tarafından Hopa Hemşinlileri’nden derlenen Hemşince ve Türkçe söylenmiş 10 türkü; biri Hemşin horonu olmak üzere Karadeniz kavalı ile çalınmış 3 ezgiden oluşan toplam 13 eser yer alıyor. Albüm, bir Ada Müzik yapımı."

- ↑ Nisanyan (2011), p. 55.

- ↑ Nişanyan (2011), p. 54.

- ↑ Suny (2015), p. xviii.

- ↑ Morris & Ze'evi (2019), p. 486.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 Karpat (1985), p. 188, Summary of Ottoman Population, 1914.

- ↑ Melkonyan (2008), p. 98.

- ↑ Eremian (1987), p. 27.

- ↑ Watenpaugh (2013), p. 291.

- ↑ Karpat (1985), p. 148, Summary: Totals for Principal Administrative Districts.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Karpat (1985), p. 168, Final Summary of Ottoman Population, 1906/7.

Sources[change | change source]

- Dündar, Fuat (2000). Türkiye nüfus sayımlarında azınlıklar (in Turkish). Doz Yayınları. ISBN 9789758086771.

- Karpat, Kemal (1985). Ottoman population 1830–1914. The University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 9780299091606.

- Simonian, Hovann H., ed. (2007). The Hemshin: History, Society and Identity in the Highlands of Northeast Turkey. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-79829-1.

- Hachikian, Hagop (2007). "Notes on the Historical Geography and Present Territorial Distribution of the Hemshinli". The Hemshin: History, Society and Identity in the Highlands of Northeast Turkey.

- Simonian, Hovann H. (2007a). "Hemshin from Islamicization to the End of the Nineteenth Century". The Hemshin: History, Society and Identity in the Highlands of Northeast Turkey.

- Vaux, Bert (2001). "Hemshinli: The Forgotten Black Sea Armenians". Harvard Working Papers in Linguistics. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University.

- Ersoy, Erkan Gürsel (2007). Ethnic identity, beliefs and yayla festivals in Çamlıhemşin. in The Hemshin. p. 320.

- Melkonyan, Ruben (2008). "The Problem of Islamized Armenians in Turkey" (PDF). Yerevan: Noravank Foundation.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Dubin, Marc S. & Lucas, Enver (1989). Trekking in Turkey. South Yarra, Vic.: Lonely Planet. ISBN 978-0-864420374.

- Balakian, Peter (2009). "Armenians in the Ottoman Empire". In Forsythe, David P. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Human Rights. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-533402-9.

- Morris, Benny; Ze'evi, Dror (2019). The Thirty-Year Genocide: Turkey's Destruction of Its Christian Minorities, 1894–1924. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-91645-6.

- Nişanyan, Sevan (2011). "Hayali Coğrafyalar: Cumhuriyet Döneminde Türkiye'de Değiştirilen Yeradları". TESEV Demokratikleşme Programı (PDF) (in Turkish).

- Eremian, Suren (1987). "Հայերը [Armenians]". Armenian Soviet Encyclopedia Volume XIII (in Armenian). Yerevan.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Bloxham, Donald (2005). The Great Game of Genocide: Imperialism, Nationalism, and the Destruction of the Ottoman Armenians. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-927356-0.

- Ghafadaryan, Karo (1984). "Անի [Ani]". Soviet Armenian Encyclopedia (in Armenian). Vol. 1. Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences.

- Grousset, René (2008) [1947]. Histoire de l'Arménie des origines à 1071 [History of the Origins of Armenia until 1071]. Paris. ISBN 978-2-228-88912-4.

- Garsoïan, Nina (2007) [1982]. Indépendance retrouvée : royaume du Nord et royaume du Sud (IXe-XIe siècle) - Le royaume du Nord" [Independence Found: Northern Kingdom and Southern Kingdom (9th - 11th Century) - The Northern Kingdom]. Histoire du peuple arménien [History of the Armenian People]. Toulouse. ISBN 978-2-7089-6874-5.

- Bournoutian, George (2002). A Concise History of the Armenian People: From Ancient Times to the Present. Mazda Publishers. ISBN 9781568591414.

- Akçam, Taner (2012). The Young Turks' Crime against Humanity: The Armenian Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing in the Ottoman Empire. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-15333-9.

- Üngör, Uğur Ümit (2015). "The Armenian Genocide in the Context of 20th-Century Paramilitarism". In Demirdjian, Alexis (ed.). The Armenian Genocide Legacy. Palgrave Macmillan UK. ISBN 978-1-137-56163-3.

- Kieser, Hans-Lukas (2018). Talaat Pasha: Father of Modern Turkey, Architect of Genocide. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-8963-1.

- Nersessian, Sirarpie Der (1962). "The Kingdom of Cilician Armenia". In Setton, Kenneth M.; Wolff, Robert Lee; Hazard, Harry W. (ed.). A History of the Crusades. Vol. II. Madison, Milwaukee, and London: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 0-299-04844-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - Hewsen, Robert H. (2001). Armenia: A Historical Atlas. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-33228-4.

- Suny, Ronald Grigor (2015). They Can Live in the Desert but Nowhere Else: A History of the Armenian Genocide. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-6558-1.

- Kurdoghlian, Mihran (1996). Պատմութիւն Հայոց [History of Armenia]. Vol. II. Athens: Հրատարակութիւն ազգային ուսումնակաան խորհուրդի [Council of National Education Publishing].

- Kévorkian, Raymond (2011). The Armenian Genocide: A Complete History. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-0-85771-930-0.

- Lang, David M. (1983). "Iran, Armenia and Georgia". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 3: The Seleucid, Parthian and Sasanid Periods. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-20092-X.

- Ahmed, Ali (2006). "Turkey". Encyclopedia of the Developing World. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-57958-388-0.

- Astourian, Stephan (2011). "The Silence of the Land: Agrarian Relations, Ethnicity, and Power". A Question of Genocide: Armenians and Turks at the End of the Ottoman Empire. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-539374-3.

- Göçek, Fatma Müge (2015). Denial of Violence: Ottoman Past, Turkish Present and Collective Violence Against the Armenians, 1789–2009. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-933420-9.

- Sertel, Savaş (2016). "Türkiye Cumhuriyeti'nin İlk Genel Nüfus Sayımına Göre Dersim Bölgesinde Demografik Yapı". Fırat Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi (in Turkish). 24 (1). doi:10.18069/fusbed.82073 (inactive 2024-01-23).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2024 (link) - Watenpaugh, Keith David (2013). ""Are There Any Children for Sale?": Genocide and the Transfer of Armenian Children (1915–1922)". Journal of Human Rights. 12 (3): 291. doi:10.1080/14754835.2013.812410. S2CID 144771307.

- Wixman, R. (2012). "K̲h̲ems̲h̲in". In P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs. (ed.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Brill.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - Payaslian, Simon (2007). The History of Armenia: From the Origins to the Present. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4039-7467-9.