Battle of South Mountain

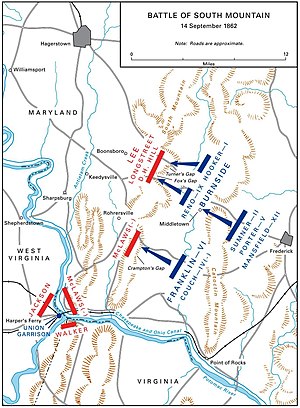

The Battle of South Mountain was fought on September 14, 1862 in Maryland’s South Mountain between Confederate and Union forces.[1] The Battle of South Mountain was a very important battle. It was the first major battle fought north of the Potomac River.[2] It was the first invasion of the Northern United States by a Confederate Army.[2] It was also here and not at Antietam where the Confederates under General Robert E. Lee were defeated and turned back.[2] The day-long pitched battle was fought for control of the three passes through the mountain: Crampton's, Turner's, and Fox's Gaps.[3]

Background[change | change source]

During the summer of 1862, the hopes of the Union that the rebellion could be easily crushed were quickly fading.[4] In July, Major General George B. McClellan failed in his attempt to capture the Southern capital at Richmond, Virginia.[4] Near the end of August, the Second Battle of Bull Run was another defeat for the Union.[5] Shortly after the battle, Lee made his plans to invade the north. Lee led his Army of Northern Virginia into Maryland on September 4, 1862.[5] Lee thought that if he took the Civil War to the Union states, a major victory might convince Great Britain and France to support the South.[5] He also thought it would make the North sue for peace. This would insure the Confederate States of America could remain an independent country.[5]

McClellan remained in command of the Army of the Potomac even though he had failed to support Major General John Pope at the Second Battle of Bull Run.[a][8] When Lee entered Maryland, in a rare exception to his usual slowness, McClellan moved more quickly to cut him off.[8] Unknown to Lee at the time, a Union soldier had found a copy of Special Order 191.[8] This was Lee's plan to split up his army.[8] McClellan learned Lee had sent General Stonewall Jackson to attack and hold the Harpers Ferry Armory. The information gave McClellan the chance to destroy Lee's army while it was still weakened by Jackson's attack on Harpers Ferry. McClellan learned of Lee's plan on September 13.[b][8] He boasted "Here is a paper with which if I cannot whip Bobbie Lee, I will be willing to go home."[8] He also sent a telegram to President Lincoln where he wrote, "I have all the plans of the rebels, and will catch them in their own trap if my men are equal to the emergency."[8] But McClellan waited another 18 hours before acting. This delay allowed Lee more time to collect all the elements of his army.[8] As Lee had moved into Maryland, he left detachments to guard two of the passes through South Mountain, Crampton's Gap and Turner's Gap.[1] These were the two most important routes through the 50-mile long South Mountain.[1] Had McClellan moved a little faster, he would have caught Lee's army scattered on the other side of the mountain.[1]

The battle[change | change source]

On September 14, the battle took place on three gaps.[5] A few Confederate regiments guarded the two northern gaps, Turner's and Fox's and Crampton's Gap to the south.[5] The Union army advanced from the east and attacked in two waves.[5] The first wave attacked Fox's Gap at about 9 am.[5] Early in the afternoon the second wave hit both Fox's and Turner's Gaps at the same time. Crampton's Gap was attacked in the late afternoon.[5]

The distance between Crampton's and Turner's Gaps is about six miles. The terrain between them made each part of the battle a separate fight.[11] The fighting went on all day at Turner's Gap and all afternoon at Crampton's Gap.[11] Turner's Gap was fought on a larger scale, was more costly and took longer than the other actions.[11] This delaying action was also a large deception by the Confederate forces. The Union forces thought the mountain was swarming with Confederates when in fact only one division guarded the passes until later in the afternoon.[12] Union forces could have easily swept them aside had they known how few there actually were.[12]

McClellan's concentrating his attack on the Confederates on South Mountain meant he did not help the garrison at the Battle of Harpers Ferry.[3] From having a copy of Lee's Special Order 191, McClellan knew Jackson was attacking the Union Forces at Harpers Ferry.[3] What little help he did send arrived too late to prevent the surrender.[3] It also gave Lee the time he needed to gather his forces together at Sharpsburg, Maryland.[3] Had McClellan moved faster and more decisively, the costly Battle of Antietam might never have taken place. Confederate losses for the day amounted to 2,700 soldiers.[1] The Union losses were 2,300 dead or wounded.[1] The Confederates were able to delay McClellan's forces by fiercely defending the gaps. This gave Lee precious time to regroup and move on to Sharpsburg where the Battle of Antietam pitted the two armies against each other again.[1] The battle of South Mountain, however, forced Lee to give up his plans for invading the North and caused him to have to defend his army.[5]

Battlefield Preservation[change | change source]

The Civil War Trust (a division of the American Battlefield Trust) and its partners have acquired and preserved 647 acres of the South Mountain battlefield. [13]

Notes[change | change source]

- ↑ McClellan was considered a great organizer but a poor choice for a battlefield commander.[6] He was too cautious and generally moved his army at a snail's pace.[6] His delays usually gave Confederate Generals ample time to retreat or regroup.[7]

- ↑ At the time he received a copy of Lee's order, McClellan was meeting with local citizens.[9] Among them was a Confederate sympathizer. He didn't know what the message said, but by McClellan's reaction he knew the Union general had learned something significant.[9] He rode off to report this news to a Confederate officer, who passed the information on to Lee.[9] Lee was surprised when McClellan moved quicker than usual but did not learn of the lost order until sometime after the Maryland Campaign.[10]

References[change | change source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 "1862 North and South clash at the Battle of South Mountain". This Day in History. A&E Television Networks, LLC. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 "The Army of the Potomac Finally Beats Bobby Lee's Boys". HistoryNet. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 "South Mountain, Crampton Gap Turner Gap, Fox Gap Civil War Maryland". AmericanCivilWar.com. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "The Maryland Campaign of 1862". Civil War Trust. Retrieved 29 June 2016.[permanent dead link]

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 "South Mountain State Battlefield". Maryland Department of Natural resources. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Why Civil War Gen. George McClellan wasn't actually a failure". 5 March 2012. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- ↑ "George B. McClellan". Civil War Trust. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 8.7 "George Brinton McClellan". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Phil Leigh (12 September 2012). "Lee's Lost Order". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- ↑ "An Invitation to Battle: Special Orders 191". Monocacy National Battlefield Maryland. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the interior. Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 "The Battle of South Mountain". Shotgun's Home of the American Civil War. Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Daniel H. Hill, Lieutenant-General, C.S.A. "The Battle of South Mountain, or Boonsboro (Fighting For Time at Turner's and Fox's Gaps)". Shotgun's Home of the American Civil War. Retrieved 2 July 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ [1] American Battlefield Trust "Saved Land" webpage. Accessed May 22, 2018.