Daniel Sickles

Daniel Edgar Sickles | |

|---|---|

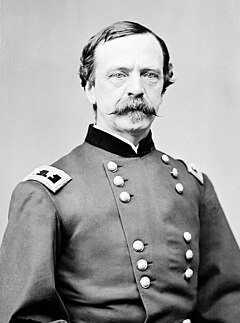

Major General Sickles circa 1862 | |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from New York's 10th district | |

| In office March 4, 1893 – March 3, 1895 | |

| Preceded by | William Bourke Cockran |

| Succeeded by | Amos J. Cummings |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from New York's 3rd district | |

| In office March 4, 1857 – March 3, 1861 | |

| Preceded by | Guy R. Pelton |

| Succeeded by | Benjamin Wood |

| United States Minister to Spain | |

| In office May 15, 1869 – January 31, 1874 | |

| Preceded by | John P. Hale |

| Succeeded by | Caleb Cushing |

| Member of the New York Senate from the 3rd district | |

| In office January 1, 1856 – March 3, 1857 | |

| Preceded by | Thomas J. Barr |

| Succeeded by | Francis B. Spinola |

| Personal details | |

| Born | October 20, 1819 New York City, New York |

| Died | May 3, 1914 (aged 94) New York City, New York |

| Resting place | Arlington National Cemetery |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | Teresa Bagioli Sickles (m. 1852–1867) Carmina Creagh (m. 1871–1914) |

| Children | 3 |

| Awards | Medal of Honor |

| Military service | |

| Nickname(s) | "Devil Dan"[1] |

| Allegiance | United States of America Union |

| Branch/service | United States Army Union Army |

| Years of service | 1861–1869 |

| Rank | |

| Commands | Excelsior Brigade III Corps |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

Daniel Edgar Sickles (1819–1914) was a controversial New York politician, diplomat, and political general during the American Civil War.[2] He was the first person to successfully use the Insanity defense as a legal defense.[2] As a result, he was acquitted of killing his wife’s lover, Francis Barton Key (son of Francis Scott Key).[2] As a general, he was a political appointee who gained his high rank strictly through political influence. Without any military experience or training, Sickles found it difficult to follow orders. In spite of his battlefield failures, he managed to get himself awarded the Medal of Honor.[3]

Early life[change | change source]

Sickles was born in New York City on October 20, 1819.[a][3] He was the son of George Garrett Sickles and Susan Marsh Sickles. At a young age he kept running away from home. His parents sent him to boarding school when he was 15 years old but he had to leave after a fight with a teacher. He became a printer's helper for a year before returning to New York City. There he developed the habit of hanging out with prostitutes and others with poor reputations. His parents decided he needed a good education and arranged for him to live in the Da Ponte household.[5] Sickles was to be tutored by the elderly Professor Lorenzo Da Ponte.[b] He was already friends with the younger Professor Da Ponte, who was in his 30s at the time. Sickles' parents hoped the friendship would be a good influence on Sickles.[5] Maria Cooke, a young American girl also lived in the household. She was about the same age as Sickles.[5] She was thought to be the natural daughter of the elder Da Ponte who adopted her.[5] Her husband, Antonio Bagioli and their infant daughter, Maria, also lived with the Da Ponte family.[5] At the time she was 3 years old, Sickles was 20. They would marry some 13 years later.

Politics[change | change source]

Sickles then studied law at New York University.[7] Afterwards he became involved in politics and was a key figure in the Tammany Hall political machine.[8] He also served as their legal counsel.[8] Through political influence he became the Corporate Council for New York City, Secretary of the United States Legation in London and later a US congressman from New York.[8] In 1852 he married Teresa Bagioli.[9] At the time he was 33 years old and she was 15.[9] Both families were opposed to the marriage at the time.[3] Only a few years later, living in Washington, D.C. as the wife of a congressman, she was described as "more like a schoolgirl than a polished woman of the world" with a "sweet, amicable manner".[4]

Leaving for London, as the assistant to James Buchanan, American minister to Great Britain, he left his young pregnant wife Teresa at home. Instead, as his traveling companion, he brought Fanny White, a notorious prostitute.[4] In London Sickles embarrassed the American delegation on more than one occasion. He refused to drink a toast to Queen Victoria. Another time he introduced Fanny White to the Queen under a false name.

Murder trial[change | change source]

In 1859 Sickles was arrested for murder. His wife had turned to another man for attention. This was Francis Barton Key, son of Francis Scott Key. Sickles repeatedly shot Key in front of his home (which was also in front of the White House. Sickles had a team of lawyers represent him, led by Edwin M. Stanton (future Secretary of State under Abraham Lincoln).[7] Sickles was released on what was the first successful plea of "temporary insanity".[7] Sickles already had a questionable reputation, but this incident made him a pariah.[10] Sickles saw the outbreak of the civil war as an opportunity to save his reputation.[10]

Civil War[change | change source]

Rank as colonel[change | change source]

In Congress, Sickles had aligned himself with Southern Democrats and was himself a pro-slavery Democrat.[11] But after the outbreak of the war, Sickles suddenly became Pro-Union.[11] His last session in Congress had ended in March so Sickles was back in New York City practicing law when the war started. In later versions of his motives for joining the Union Army he stated he thought he could best serve the Union by raising a regiment.[11] Republican President Lincoln needed the support of Democrats and apparently saw Sickles as one he could use.[11] After raising a regiment, then a brigade which he named the Excelsior Brigade, Sickles assumed he would be given the rank of brigadier general (a colonel commanded a regiment while a brigadier general commanded a brigade).[11] But officially, he remained a colonel of the first regiment, even though he commanded the entire brigade.[11] New York Governor Edwin D. Morgan decided there were too many regiments from New York City and ordered Sickles to disband some of the regiments.[11] As a result, Sickles would not get a brigadier general's commission. Going around the governor, Sickles went to Washington to meet with Lincoln. The President agreed to enlist the disbanded regiments as United States Volunteers. Finally on July 20, 1861 they received orders to report to Harpers Ferry, West Virginia. In September, Sickles was nominated as a brigadier general of volunteers, but his confirmation was delayed for several months by the United States Senate.[11] Sickles brigade spent most of 1861 in lower Maryland. Sickles frequently visited the Lincolns in Washington during this time. In March 1862, his command was attached to General Joseph Hooker in the Army of the Potomac. That same month, Sickles' brigadier general commission was turned down by the Senate.[11] The Excelsiors saw their first combat that month. Sickles personally led a reconnaissance. Then on April 6, he left the Excelsiors for Washington to protest his not being commissioned a brigadier general. While his unit fought in the Peninsula Campaign, Sickles remained in Washington. Lincoln again nominated him for general and on May 3, 1862 the Senate confirmed him.[12]

Brigadier general[change | change source]

On May 24, "brigadier general" Sickles was ordered to report back to Hooker. He was given command of Hooker's 2nd Brigade. Sickles saw his first major engagement at the Battle of Seven Pines.[12] Sickles next saw action at the Seven Days Battles. Hooker's advance did not go well due in part to Sickles' brigade having difficulties moving through the swamps then meeting heavy Confederate resistance.[12] When some of his men broke and ran to the rear, Sickles was only able to get a few to return. Nonetheless, Hooker's report noted Sickles gallantry in trying to rally his men.[12] He did not stay long and missed the Second Battle of Bull Run and the Battle of Antietam, being in New York recruiting men for his brigade.[12] When Ambrose Burnside replaced George B. McClellan as commander of the Army of the Potomac, both Hooker and Sickles were moved up to command larger units.[12] Sickles still had hardly any battlefield experience yet was now leading Hooker's old second division of III Corps.[12] Sickles was busy getting New York newspapers and Washington insiders to promote his image as a battle hardened fighting general.

In December 1862, at the Battle of Fredericksburg, Sickles brigade did not see battle until the third day. He and his troops watched as Union troops fought uphill against Lee's Confederates.[13] After 2:00 p.m. Sickles was finally ordered to the front. Leading his men they found the battle to mostly be over in their section. They secured their position against limited sniper fire and a few Skirmishes but otherwise did not see any fighting.[13]

Major general[change | change source]

When Burnside was replaced as commander of the Army of the Potomac, Hooker was moved up to replace him.[14] In the new assignments resulting from the change, and even though he had little battlefield experience, Sickles was given temporary command of III Corps.[14] But again, the Senate did not confirm his promotion to Major General. Finally, on March 9 (with his rank to date back to November 29), the Senate confirmed his promotion. By the end of March Sickles was officially a major general.[14] Unlike earlier battles, at the Battle of Chancellorsville, Sickles saw action.[14] As Sickles observed Confederate general Stonewall Jackson's flanking maneuver, without orders he pushed forward with two-thirds of his corps to go after the Confederates.[8] This left XI Corps on his right completely isolated. Jackson's confederates then made a crushing attack on XI Corps. Sickles leaving his assigned position was a major factor in the Confederate victory.[8] This started a feud between Hooker and Sickles that continued into the Battle of Gettysburg. Hooker blamed Sickles for the defeat at Chancellorsville.[8]

Gettysburg[change | change source]

On June 27, Hooker resigned as commander of the Army of the Potomac.[3] Among the corps commanders suggested to replace him, the New York Herald actually suggested Sickles as the best commander for the job.[3] On June 28, three days before the battle of Gettysburg, Lincoln appointed general George G. Meade to replace Hooker. On July 1, the first day ended in Confederate victory. Meade worked to quickly put his forces in place for the next day's battle. Early on the morning of July 2, Meade sent a message to Sickles with instructions to place his 12,000-man corps on Cemetery Ridge. He was specifically ordered to connect to general Winfield Scott Hancock's II Corps on his right, and extend his line to Little Round Top on his left.[3]

Sickles, not impressed with his new commander or his orders. He rode to Meade's headquarters about 11:00 a.m. and waited to see Meade. But the commander was busy at the time. Feeling ignored Sickles returned to his troops. He decided he did not like his orders. A mile to his front was Emmitsburg Road, which was higher ground than he was assigned to occupy. He also did not like the fact there were rocks and trees among his line. Sickles, without orders or without informing the other corps commanders moved his corps forward about one mile. This left Hancock's left flank completely open and a large break in the line where his corps was supposed to be. The new position he chose was wider than the one he abandoned and he did not have enough men to cover it completely.[3] The middle of his line formed a salient (a right angle in the line that could be attacked from two directions).[3] Brigadier general Henry Hunt, the artillery chief, inspected the new position with Sickles and pointed out the problems. He said he had to check back with Meade to see if the orders he gave Sickles could be changed.[3] Sickles made the move anyway.[3] Within an hour, his entire III Corps was nearly wiped out by Confederate general James Longstreet's corps.[3] Sickles himself was nicked by a cannonball which shattered his leg.[3] He was carried off the field and his right leg was amputated a few hours later.[3] His injury may have saved him from a court-martial for disobeying orders, but his days as a field commander were at an end.[3]

After Gettysburg[change | change source]

After Sickles lost his right leg, he gained fame for donating it to the Army Medical Museum in Washington, DC.[7] He sent it with a card which read, "With the Compliments of Major General D.E.S.".[7] The leg is on display today at the Army Medical Research and Materiel Command headquarters building at Fort Detrick, Maryland.[15] After his recovery, Lincoln sent Sickles to the South where he was to look into the effect of slavery on African Americans. He was also to give suggestions for the future Reconstruction of the South.[7]

After the Civil War he held a number of different positions. He was military governor of North and South Carolina but was removed by President Andrew Johnson in 1867.[2] He retired from the army in 1869.[2] From his retirement to 1872 he was appointed a U.S. minister to Spain by President Ulysses S. Grant. While there Sickles managed to engage in "undiplomatic relations" with the Spanish queen.[16] He served one more term in Congress from 1893–1895 but was defeated for reelection in 1986.[2] In 1897, after 34 years of lobbying, Sickles was able to get himself awarded the Medal of Honor.[17]

In New York he was a New York City sheriff and chairman of the New York State Monuments Commission. In 1912, he was removed from the commission for allegedly misusing funds. He also was an important part of establishing the Gettysburg National Battlefield Park.[7] On May 3, 1914, Sickles died in New York City of a cerebral hemorrhage.[7] Sickles was buried at Arlington National Cemetery.[7]

Notes[change | change source]

- ↑ His date of birth is questionable. Most of his biographers say he was born on October 20, 1819.[4] Other sources—some provided by Sickles—give years of birth ranging from 1819 to 1825.[4] His New York Times obituary gave his age as 91 years old when he died (which would mean he was born in 1823). His military record states that in 1861 he was 39 years old (indicating 1821 as his birth year).[4] In at least one interview given to reporters, he claimed he was born in 1825.[4] The 1910 United States Census said "about 1826". One theory for the different dates is that his parents may not have married until 1820.[4] Later dates might have been given to hide the fact he was born "out of wedlock" (before his parents married).[4]

- ↑ The elder Lorenzo Da Ponte was at the time about 90 years old.[5] In his life he had been a Catholic priest, a close friend of Giacomo Casanova, had written librettos for Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and had worked for the Holy Roman Emperor, Joseph II.[5] He had immigrated to the United States and at age 80 became a professor of Italian language at Columbia University.[6] Da Ponte gave private lessons in Italian language and literature (mostly to young women).[6]

References[change | change source]

- ↑ Devil Dan Sickles' Deadly Salients Archived 2011-06-11 at the Wayback Machine - America's Civil War magazine, November 1998

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 "Daniel Sickles". History. A&E Television Networks, LLC. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 "Daniel Sickles". HistoryNet. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 James A. Hessler, Sickles at Gettysburg: The Controversial Civil War General Who Committed Murder, Abandoned Little Round Top, and Declared Himself the Hero of Gettysburg (New York: Savas Beatie, 2009), pp. 1-5

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 Thomas Keneally, American Scoundrel: The Life of the Notorious Civil War General Dan Sickles (New York: Anchor Books, 2003), pp. 3-7

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Jack Beeson. "Da Ponte, Macdowell, Moore, and Lang: Four Biographical Essays". Columbia University. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 7.8 "Daniel E. Sickles, Major General, October 20, 1819 - May 3, 1914". Civil War Trust. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 Robert P. Broadwater, Gettysburg as the Generals Remembered It: Postwar Perspectives of Ten Commanders (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2010), p. 36

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Robert Wilhelm (November 10, 2009). "Dan Sickles's Temporary Insanity". Murder by Gaslight. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Kevin Baker (April 14, 2002). "The Man Who Got Away With Everything". The New York Times. Retrieved August 24, 2016.p. 2

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 11.7 11.8 James A. Hessler, Sickles at Gettysburg: The Controversial Civil War General Who Committed Murder, Abandoned Little Round Top, and Declared Himself the Hero of Gettysburg (New York: Savas Beatie, 2009), pp. 21–28

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 James A. Hessler, Sickles at Gettysburg: The Controversial Civil War General Who Committed Murder, Abandoned Little Round Top, and Declared Himself the Hero of Gettysburg (New York: Savas Beatie, 2009), pp. 29–33

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 James A. Hessler, Sickles at Gettysburg: The Controversial Civil War General Who Committed Murder, Abandoned Little Round Top, and Declared Himself the Hero of Gettysburg (New York: Savas Beatie, 2009), pp. 35–40

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 James A. Hessler, Sickles at Gettysburg: The Controversial Civil War General Who Committed Murder, Abandoned Little Round Top, and Declared Himself the Hero of Gettysburg (New York: Savas Beatie, 2009), pp. 42–50

- ↑ "USAMRMC to Exhibit Amputated Leg of Union Major General". National Museum of Health and Medicine. Archived from the original on October 20, 2016. Retrieved August 26, 2016.

- ↑ "Mary's Charlatans: General Dan Sickles (1819-1914)". Mr. Lincoln's White House. The Lehrman Institute. Retrieved August 26, 2016.

- ↑ "Daniel Edward Sickles (1819-1914)". North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources. Archived from the original on July 20, 2016. Retrieved August 26, 2016.

Other websites[change | change source]

- 1819 births

- 1914 deaths

- Ambassadors of the United States

- American Civil War generals

- American police officers

- Politicians from New York City

- United States Army Medal of Honor recipients

- United States representatives from New York (state)

- Democratic Party (United States) politicians

- Military people from New York (state)