Horatio Alger

Horatio Alger, Jr. | |

|---|---|

Horatio Alger, Jr., about 1868 | |

| Born | January 13, 1832 Chelsea, Massachusetts, United States |

| Died | July 18, 1899 (aged 67) South Natick, Massachusetts |

| Pen name | Carl Cantab Arthur Hamilton Caroline F. Preston Arthur Lee Putnam Julian Starr |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Harvard, class of 1852 |

| Genre | Boys' books Magazine stories Sentimental poetry |

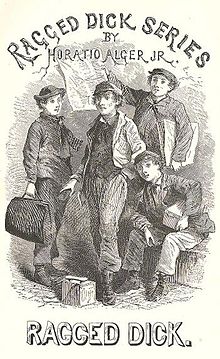

| Notable works | Ragged Dick (1868) |

Horatio Alger, Jr. (January 13, 1832 – July 18, 1899) was an American writer. He wrote magazine stories and poems, a few novels for adults, and 100 plus boys' books. His boys' books were hugely popular.

Alger was born in Massachusetts, and attended Harvard College. He became a Unitarian minister, but his career as a clergyman was brief. It ended when his congregation charged him with child molestation. Criminal charges were not placed against him, but his career in the church was finished.

He moved to New York City to become a professional writer. In 1868, Alger found his place in the literary world with his fourth boys' book, Ragged Dick. This book is about a poor shoe shine boy in New York City who rises to middle class comfort and security through hard work, honesty, and a little luck. The book was a great success.

Alger continued to write boys' books. They were similar to Ragged Dick in theme and other details. Characters such as the poor but honest boy, the snobbish youth, and the greedy lawyer appeared in one book after another. Details changed from book to book, but the essentials remained the same. Boys loved the books.

By the 1870s, boys' tastes had changed. They wanted cowboys, hunters, and Indians. Alger headed west to gather material for future books. The trip had little impact on his writing however. He wrote four books set in the west called the "Pacific Series", but they were stuck in Alger's rags-to-riches rut.

In the last decades of the 19th century, boys' tastes changed again. They wanted violence, murder, and other sensational themes. Alger gave them what they wanted. Public librarians did not like these books. They wondered whether children should be reading them. They began throwing Alger's books away.

Alger passed his last years quietly. He went to the theatre, visited old friends, and kept in touch with the boys he had helped over the years. He based new books on those of his past. He died at his sister's home in South Natick, Massachusetts, in 1899.

Biography[change | change source]

Boyhood[change | change source]

Horatio Alger, Jr. was born in Chelsea, Massachusetts on January 13, 1832. His parents were Horatio Alger, a Unitarian clergyman, and his wife Olive Augusta Fenno Alger. Horatio was the eldest of the couple's five children.[1] He was a descendant of several Plymouth Pilgrims, a brigadier general of the American Revolution, and a member of the Constitutional Convention.

Horatio was a sickly child. He had asthma and myopia. He was timid and shy. He was bullied by the bigger boys in the neighborhood.[2] His father decided Horatio would become a clergyman. He taught the boy Greek and Latin. He took Horatio along with him on parish house calls to give the boy a sense of a minister's duties.[3][4]

Education[change | change source]

In 1842, Horatio entered the Chelsea Grammar School. He was a good student.[5] His father had money troubles about this time. He took a better paying job in Marlborough, Massachusetts, a farming community about 25 miles west of Boston. The Alger family moved there in December 1844.[2][5]

In Marlborough, Horatio went to a prep school called Gates Academy.[5] He began writing poems and short stories. He sent his writings to local newspapers.[6] The family's money troubles made a lasting impression on Horatio. Money ills like foreclosure and bankruptcy became themes in his books. He had fond memories of Marlborough, despite the family's woes. Quiet country villages are settings in many of his boys' books.[7]

Alger entered Harvard College in 1848.[4][6] He became a professional writer the following year when he sold two essays and a poem to a Boston magazine.[8] He was elected to Phi Beta Kappa, a fraternity for outstanding scholars.[9] He graduated in 1852, ranking eighth in a class of eighty-eight.[10] He went to Harvard Divinity School in 1853.[11] He quit the same year to take a job as an assistant editor with a Boston magazine.[12] He hated editing, and quit in 1854.

He taught briefly in two New England boys' boarding schools.[13][14] In 1856 he published Bertha's Christmas Vision, a book of short stories and poems. He returned to the Harvard Divinity School in 1857, and graduated in 1860.[15] His health was poor. He was rejected for military service during the American Civil War, but wrote for the Union cause instead.[16][17] His first boys' book Frank's Campaign was published in 1864.[18]

Alger's ministry[change | change source]

On December 8, 1864, Alger became pastor of the First Unitarian Church and Society in Brewster, Massachusetts.[19] The people of Brewster liked him. He was a good speaker. He played ball games with the boys, and took walks with them.[20] He kept writing stories, and sent them to a boys' magazine in Boston called Student and Schoolmate. He wrote another boys' book, Paul Prescott's Charge. It was published in September 1865. The critics gave it good reviews.[21]

Early in 1866, the people of Brewster accused Alger of sexually molesting two boys. These boys were 13 and 15 years old. Three men of the church discovered that this was true.[22] Alger said that he had been "unwise", and quit his job with the Brewster church. He left town quickly, and went to his parents' home in South Natick, Massachusetts.[23]

His father got in touch with Unitarian church authorities in Boston. He promised them that his son would never take a job in the church again. These authorities were satisfied. Further action was not taken. This was probably done so Alger's father would not be publicly embarrassed. Some members of the Brewster church wanted Alger put to death as the Bible ordered.[24] Alger never mentioned his days in Brewster again.

Life in New York City[change | change source]

In April 1866, Alger moved to New York City to become a professional writer.[25][26] In the summer of 1866, he wrote "John Maynard". This is a poem about a real shipwreck on Lake Erie. It brought Alger the notice of other writers when it was published in Student and Schoolmate in January 1868. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, for example, sent a letter of compliments to Alger. Children loved the poem and read it aloud in classrooms for many years.[27]

Alger loved the attention, but he needed money. He rewrote some of his old stories. One became his third boys' book Charlie Codman's Cruise. Although readers liked the book, it did not make much money.[28] Alger made more money with the boys' stories he published in Student and Schoolmate. His writings for boys satisfied his two biggest concerns at this time—the need for a good income and the need to atone for his crimes in Brewster.[29]

Alger met many poor boys on the docks and streets of New York City. These boys had been made homeless by the Civil War. They had drifted to the city looking for work. Alger collected material from them about their lives in the city and the lives of the poor. He put this material into his books.

Some of these real boys became characters in his books. Johnny Nolan, for example, was one of the first boys Alger met in New York City. He appears in several of Alger's early books as a lazy, carefree street boy. Alger often had a crowd of street boys in his apartment. They would play while Alger sat calmly at his desk writing a page or two for his latest book. There is no record of sexual misconduct on Alger's part during this period.[30]

Newsboys Lodging House[change | change source]

In 1866, Alger began visiting the shelters for homeless boys in the city such as the YMCA, the Five Points Mission, and the Newsboys Lodging House. This last shelter was opened in 1854 by people concerned about the welfare of street children.[31]

At this shelter, a homeless boy could have a hot meal and a clean bed for a few pennies. He could come and go as he pleased. There was even something like a savings bank at the shelter.[32]

Alger had his own room, a desk, and a bed at the Newsboys Lodging House. He wandered about in slippers and an old sweater talking to the boys. In this way, he gathered the material he needed for his stories.[33] In the introductions to his books, Alger asked his readers to give generously to such shelters.[34]

Success with Ragged Dick[change | change source]

In October 1866, Reverend Henry Morgan published Ned Nevins, the Newsboy; or, Street Life in Boston. It was a great success. Alger sharpened his pencils and began a similar story. He wanted readers to believe his story was a realistic picture of street life, but it was actually a sentimental story that carefully avoided any mention of the sex and violence that threatened street boys every day.[35]

In January 1867, Alger's Ragged Dick began serialization (publication in parts) in Student and Schoolmate. The story is about a poor shoe shine boy's rise to middle class comfort and security. The book was a huge success. Boys' loved it. It had all sorts of exciting adventures in a big city. It had lots of street slang. It exposed the swindles and crimes practiced by big city crooks. The story surprised and delighted boys in small town America. They had never read of such things.

The parts of the story were gathered together and published as a book in 1868.[36] It became Alger's all-time bestseller. It is the first in the 6-volume Ragged Dick Series. This series follows the further adventures of Ragged Dick and his friends. Alger wrote almost entirely for boys after the success of Ragged Dick. He had found his place in literary America.[37]

Trips West[change | change source]

In 1875, Alger's stories about street boys were growing stale.[38] Boys' tastes had changed. They wanted exciting stories about hunters, cowboys, and Indians. Alger went West to look for material.

He arrived in California in February 1877.[39] He travelled the length of the West Coast, then returned to New York late in the year.[40] In 1878, Alger went West again.

These two trips had little impact on his stories. He wrote a few dull books with western settings in the following years, but remained stuck in his "poor boy makes good" formula.[41][42]

Backlash[change | change source]

In the early 1870s, librarians, teachers, ministers, and others interested in the well being of the young said the stories by Alger and other boys' writers were not suitable for children. These people thought such books were too violent.

Critics said his popularity among boys was due to his "sensational" style. In 1877, one minister wondered why the public library allowed children to read books that could only demoralize and weaken them. He complained about "the endless reams of such drivel poured forth by Horatio Alger, Jr."[43] In 1879, a public library in Vermont was the first library in America to throw away Alger's books.[44] Other public libraries then did the same.[45][46]

Alger's publisher A. K. Loring of Boston, Massachusetts was a victim of this censorship effort. The company had relied on Alger's stories to make them money, but Loring went bankrupt in 1881. These efforts to get rid of Alger's books were defeated. People started reading them again after his death.[44][47]

Biographies[change | change source]

In 1881, Alger wrote President James A. Garfield's biography, From Canal Boy to President. He thought this was serious literary work. He hoped the book would make him famous. He paid no attention to the facts however. Instead, he filled the book with exciting details to thrill boy readers. The book was a success. It sold 20,000 copies. The publisher wanted to bring out an entire series about the great men of America.[48][49]

Alger was hired to write Abraham Lincoln's biography. Once again, he paid no attention to the facts. He wrote thrilling details for boy readers. The book did not sell well. He went on to write a biography of Daniel Webster. Then he stopped writing biographies. He said such books were time-consuming and required too much work. The publisher dropped the idea of a series.[48][49]

Last years[change | change source]

Alger led a quiet life in the years before his death. He dined out, went to the theater, and visited old friends. He kept in touch with the boys he had taken an interest in over the years. He read parts of Ragged Dick to boys' groups.[50]

He was a Republican, and took an interest in politics.[51] He forgot his past life in Brewster, and wrote of his days as a clergyman: "I studied theology chiefly as a branch of literary culture and without any intention of devoting myself to it as a profession."[52]

The quality of his writing deteriorated in his last years. He reworked his old books.[53] Times had changed. Boys wanted more excitement and violence in books. Alger gave them what they wanted.[54]

Critics complained of the sameness in his characters, themes, and other details. Alger defended his work. He said that his readers did not object to the "family resemblances", so why should the critics?[55]

Death[change | change source]

In the last years of the 1890s, Alger's books did not sell well. His income dwindled.[56] In 1896, he had (what he called) a nervous breakdown. He moved to his sister's house in South Natick, Massachusetts. He died there on July 18, 1899 after an asthma attack.[50][57] He was almost forgotten by the public in his last years. His death received little attention in the newspapers.[58]

Alger once estimated that he made no more than $100,000 during his New York years (1866–1896). He was paid about US$250 for each of his stories published in parts in magazines. He received a small amount of money when each story was published in book form. He was not rich at the end of his life, but he was not poor either. He left only small amounts of money to family and friends. He also left them his copyrights, his manuscripts, and his personal library.[58]

Renewed interest[change | change source]

People became interested in Alger's books in the twenty years after his death. This was the Progressive Era. It was a time when people wanted honest business practices, equal opportunity, and a return to old-fashioned values. About seventeen to twenty million Alger books were printed and sold during this time.[59]

People lost interest in Alger's books in the early 1920s. His leading publisher stopped printing the books.[59] Alger was competing at that time with The Rover Boys, Tom Swift, and other popular books for boys.[60] Surveys in 1932 and 1947 indicated that very few children had read or even heard of Alger.[59][61] In 1932 (one hundred years after Alger's birth), The Literary Digest declared him "forgotten".[59]

Just before his death, Alger claimed to have sold 800,000 books during his years as a writer.[43] After his death, his books sold at one million per year. More Alger books were sold per year after his death than were sold during the writer's lifetime.[62] Edward Stratemeyer, the head of a company that published a great amount of boys' fiction, adopted Alger's heroic moral stance to his own books for boys. Other writers adjusted Alger's morality and ethics to suit more money-focused times. These revisions remained strong until the beginning of the Great Depression in 1929.[63]

Boys' books[change | change source]

The quality of his literary allusions however makes his writing distinctive. These allusions set his work apart from the books cranked out in the "fiction factories" of the day. Great authors alluded to in Alger's boys' book include Shakespeare, Milton, Longfellow, Cicero, Horace, Alexander Pope, Joseph Addison, and dozens of others. The Bible is referenced in more than half of his works. These allusions reveal Alger's knowledge of literature and "enhance the literary quality of his work".[64]

The most prevalent theme in Alger's novels is the "rise to respectability". Business success was important to the young Alger hero, but even more important was becoming a respected citizen. This does not mean a rise to wealth and riches. Many of Alger's books end with their young heroes getting modest clerical jobs in large firms. These jobs offer chances to rise further. Alger's heroes deserve their good fortune because they are virtuous young men. Alger was mainly a moral instructor for the young. He was content to guide boys on the path of piety and moral virtue rather than business success.[65] Other themes in his works include Strength through Adversity, Beauty versus Money, the Country versus the City, the Old World versus the New World, and the Search for an Identity.

Alger's books are filled with stereotypical characters and dramatic highpoints (setpieces) played over and over again in book after book. One such setpiece is the struggle between the virtuous young hero and a snobbish youth. These setpieces always end with the snobbish youth getting his just deserts. This particular setpiece likely has its source in the childhood bullying Alger suffered from neighborhood boys in Chelsea.

Other setpieces include the cold, unfeeling lawyer threatening the young hero and his widowed mother with foreclosure (another setpiece taken from Alger's childhood), and the brutal poorhouse staff making the young hero's life miserable while he dwells under their roof. Alger's young readers never tired of these stock characters and setpieces.[66]

In the 1970s Alger's work was regarded by readers and scholars as almost unreadable. He received a new lease on literary life when his homosexuality became known. Edwin Hoyt speculated in Horatio' Boys (1974) that Alger might become of interest to communities outside the literary one, and may even attain a status to rival that of Oscar Wilde.[67]

Literary influences[change | change source]

Alger's success stories provided material for satirists. One of the earliest satires is William Dean Howells' The Minister's Charge; or, The Apprenticeship of Lemuel Barker (1887). This novel satirizes in a serious, realistic way Alger's "country boy makes good" theme. Stephen Crane satirizes the Alger success story with a ridiculous version of one in "A Self-Made Man: An Example of Success That Anyone Can Follow" (1899).[68]

In the 20th century, F. Scott Fitzgerald satirized Alger in his play The Vegetable: or From President to Postman (1922), the Dan Cody episode in The Great Gatsby (1925), and the short story "Forging Ahead" (1929). Nathaniel West parodied Alger in A Cool Million (1934). John Seelye did the same in Dirty Tricks; or, Nick Noxin's Natural Nobility (1973). Glendon Swarthout followed the sexual misadventures of an Alger anti-hero in Luck and Pluck (1973). William Gaddis took the Alger success story to absurd lengths in JR.[68]

Legacy[change | change source]

The Horatio Alger Association is a "nonprofit educational organization, [that] was established in 1947 to dispel the mounting belief among the nation's youth that the American Dream was no longer attainable." The Association awards scholarships to young people who pursue their own idea of the American Dream.[69]

An annual street fair (once the Horatio Alger Street Fair) was held annually in October in Marlborough, Massachusetts. The Fair became the Heritage Festival in 2006, and Alger's name dropped from the event. It originally used Alger's name because he lived in a house in the town as a teenager, but accusations of child sexual abuse forced fair organizers to part company with Alger.[70]

Notes[change | change source]

- ↑ Scharnhorst 1980, pp. 17–18

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Hoyt 1974, pp. 10–11

- ↑ Hoyt 1974, pp. 7–9

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Alger 2008, p. 277

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Hoyt 1974, p. 14

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Scharnhorst 1985, p. 14

- ↑ Scharnhorst 1980, p. 18

- ↑ Hoyt 1974, p. 18

- ↑ Hoyt 1974, p. 22

- ↑ Scharnhorst 1985, pp. 18–23

- ↑ Scharnhorst 1985, pp. 27–28

- ↑ Scharnhorst 1985, p. 29

- ↑ Hoyt, 1974 & pp. 24, 28

- ↑ Scharnhorst 1985, p. 33

- ↑ Scharnhorst 1980, p. Chronology

- ↑ Scharnhorst 1985, p. 54

- ↑ Scharnhorst 1980, p. 26

- ↑ Hoyt 1974, pp. 40–48

- ↑ Scharnhorst 1980, p. 28.

- ↑ Hoyt 1974, pp. 2-4.

- ↑ Scharnhorst 1985, p. 65

- ↑ Scharnhorst 1985, p. 88.

- ↑ Scharnhorst 1980, pp. 29-30.

- ↑ Scharnhorst 1985, pp. 1-3.

- ↑ Scharnhorst 1985, pp. 67–68, 71

- ↑ Hoyt 1974, p. 63

- ↑ Scharnhorst 1985, pp. 75–76

- ↑ Scharnhorst 1985, pp. 71–72

- ↑ Scharnhorst 1980, pp. 30–32

- ↑ Scharnhorst 1985, p. 77.

- ↑ Scharnhorst 1985, pp. 77-78.

- ↑ Scharnhorst 1985, p. 79.

- ↑ Hoyt 1974, pp. 88, 90, 97.

- ↑ Scharnhorst 1985, p. 78.

- ↑ Scharnhorst 1985, p. 81.

- ↑ Scharnhorst 1980, p. 34.

- ↑ Scharnhorst 1980, p. 48.

- ↑ Hoyt 1974, pp. 184–86

- ↑ Hoyt 1974, p. 187

- ↑ Hoyt 1974, pp. 187–88

- ↑ Hoyt 1974, p. 190

- ↑ Scharnhorst 1985, pp. 105, 111–17

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Scharnhorst 1980, p. 140.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Scharnhorst 1985, p. 117.

- ↑ Scharnhorst 1985, p. 117-120.

- ↑ Nackenoff, p. 250.

- ↑ Nackcenoff, p. 250.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Hoyt 1974, pp. 207–10

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Scharnhorst 1985, pp. 121–23

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Scharnhorst 1980, p. 46.

- ↑ Hoyt, p. 227.

- ↑ Hoyt, p. 229.

- ↑ Scharnhorst 1980, pp. 44–45.

- ↑ Hoyt, p. 231.

- ↑ Hoyt, p. 230.

- ↑ Scharnhorst 1980, pp. 46.

- ↑ Hoyt, p. 232.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 Scharnhorst 1980, p. 47.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 59.2 59.3 Scharnhorst 1980, p. 141.

- ↑ Hoyt, p. 233.

- ↑ Hoyt, p. 251.

- ↑ Scharnhorst 1985, p. 149.

- ↑ Scharnhorst 1980, p. 142.

- ↑ Scharnhorst 1980, pp. 73–74

- ↑ Scharnhorst 1980, pp. 145–46

- ↑ Hoyt 1974, pp. 245–246

- ↑ Hoyt 1974, pp. 241–42

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 Scharnhorst 1980, p. 145

- ↑ "Horatio Alger Association". Archived from the original on 2013-11-05. Retrieved 2013-07-27.

- ↑ Street fair drops Alger name

References[change | change source]

- Alger, Horatio, Jr. (2008), Hildegard Hoeller (ed.), Ragged Dick, Norton Critical Editions, W. W. Norton & Company, ISBN 978-0-393-92589-0

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Alger, Horatio, Jr.; Trachtenberg, Alan (1990), Ragged Dick, Signet Classic, ISBN 978-0-451-52480-5

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Hoyt, Edwin P. (1974), Horatio's Boys, Chilton Book Company, ISBN 978-0-8019-5966-0

- Nackenoff, Carol (1994), The Fictional Republic, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-507923-4

- Scharnhorst, Gary (1980), Horatio Alger, Jr., Twayne Publishers, ISBN 978-0-8057-7252-4

- Scharnhorst, Gary; Bales, Jack (1985), The Lost Life of Horatio Alger, Jr., Indiana University Press, ISBN 978-0-253-14915-2

Other websites[change | change source]

- Works by or about Horatio Alger at Internet Archive (scanned books original editions color illustrated)

- Works by Horatio Alger at Project Gutenberg (plain text and HTML)

- The Complete "Ragged Dick" Series on kindle.

- Horatio Alger Books On-Line 2 Archived 2005-03-08 at the Wayback Machine 18 of Alger's works (with A Fancy of Hers, unique to this collection)

- Horatio Alger Books On-Line 3 Archived 2021-03-01 at the Wayback Machine 3 of Alger's works (with The Maniac's Secret, unique to this collection)

- Horatio Alger research page at the University of Rochester

- Horatio Alger Society Home Page

- The Horatio Alger Association of Distinguished Americans

- The Horatio Alger Collection at Northern Illinois University Archived 2008-05-16 at the Wayback Machine