Naked mole rat

| Naked mole rat Temporal range: early Pliocene – Recent

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Heterocephalus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Heterocephalus glaber | |

| |

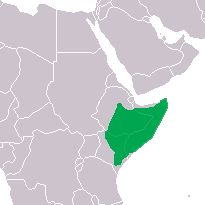

| Distribution of the Naked Mole Rat | |

The naked mole rat (Heterocephalus glaber), (or sand puppy) is a burrowing rodent. The species is native to parts of East Africa. It is one of only two known eusocial mammals (the other is the Damaraland mole rat). Both species are similar in many respects.

The animal has unusual features, adapted to its harsh underground environment. The animals do not feel pain in their skin. They also have a very low metabolism.

Physical description[change | change source]

Typically, the animals are between eight and ten centimetres long, and weigh about 30 grams. Their eyes are quite small, and they do not see very well. Their legs are thin and short. Nevertheless, they are very good at moving underground and can move backward as fast as they can move forward. They have large, protruding teeth, which they use to dig. Their lips are sealed just behind the teeth to prevent soil from filling their mouths while digging. They have little hair and wrinkled pink or yellowish skin.

The naked mole rat is well adapted for the limited availability of oxygen within the tunnels that are its habitat: its lungs are very small and its blood has a very strong affinity for oxygen, increasing the efficiency of oxygen uptake. It has a very low respiration and metabolic rate for an animal of its size, about two thirds that of a mouse of the same size. It only uses very little oxygen. In long periods of hunger, such as a drought, its metabolic rate can reduce by up to twenty-five percent.

The naked mole rat can only regulate its body temperature in the typical mammalian fashion over a relatively narrow range of temperatures. Outside this range, it overheats or cools. It can overcome this by its behaviour. When cold, naked mole rats huddle together or bask in the shallow parts of their burrow systems. When they get too hot, they retreat to the deeper, cooler parts of their tunnel system.[1]

Ecology and behavior[change | change source]

Distribution and habitat[change | change source]

The naked mole rat is native to the drier parts of the tropical grasslands of East Africa, mainly South Ethiopia, Kenya, and Somalia.

Colonies averaging 75-80 individuals live together in complex systems of burrows in arid African deserts. The tunnel systems built by naked mole rats can stretch up to two or three miles in cumulative length.[2]

Social structure and reproduction[change | change source]

The naked mole rat is one of the two species of mammals that are eusocial. Only one female (the queen) and one to three males reproduce, while the rest of the members of the colony are workers. Workers do different things.[2] Some are tunnellers, expanding the large network of tunnels within the burrow system, and some primarily as soldiers, protecting the group from outside predators.

This eusocial organisation social structure, similar to that found in ants, termites, and some bees and wasps, is very rare among mammals.

The relationships between the queen and the breeding males may last for many years. "Reproductive suppression" causes the other females not to reproduce: the infertility in the working females is only temporary, and not genetic. Queens live from 13 to 18 years, and are extremely hostile to other females behaving like queens, or producing hormones for becoming queens. When the queen dies, another female takes her place, sometimes after a violent struggle with her competitors.

Males and females are able to breed at one year of age. Gestation is about 70 days. A litter is usually from three to twelve pups, but may be as large as 28. The average litter size is 11.[3] In the wild, naked mole-rats usually breed once a year, if the litter survives. In captivity, they breed all year long and can produce a litter every 80 days.[1] The young are born blind and weigh about 2 gm. The queen nurses them for the first month; after which the other members of the colony feed them feces until they are old enough to eat solid food.

Diet[change | change source]

Naked mole rats feed primarily on very large tubers (weighing as much as 1000 times the body weight of a typical mole rat) that they find deep underground through their mining operations, but also eat their own feces (coprophagia).[2] A single tuber can provide a colony with a long-term source of food—lasting for months, or even years,[2] as they eat the inside but leave the outside, allowing the tuber to regenerate. Symbiotic bacteria in their intestines help them digest the fibres.

Longevity[change | change source]

The naked mole rat is also of interest because it is extraordinarily long-lived for a rodent of its size (up to 28 years) and holds the record for the longest living rodent.[4] The secret of their longevity is debated, but is thought to be related to the fact that they can shut down their metabolism during hard times, and so prevent oxidative damage. This has been summed up as "They're living their life in pulses".[5]

Due to their extraordinary longevity for such a small rodent, an international effort was put into place to sequence the genome of the naked mole rat.[6] Results came in 2011 and 2014.[7] Transcriptome sequencing showed that genes related to mitochondria and oxidation reduction processes have high expression levels in the naked mole-rat as compared to mice. This may contribute to their longevity.[8]

The DNA repair transcriptomes of the liver of humans, naked mole rats and mice were compared.[9] The maximum lifespans of humans, naked mole rats, and mice are respectively ~120, 30 and 3 years. The longer-lived species, humans and naked mole rats, expressed DNA repair genes at a higher level than did mice. In addition, several DNA repair pathways in humans and naked mole rats were up-regulated compared with mice. These findings suggest that increased DNA repair makes for greater longevity. The findings are consistent with the DNA damage theory of aging.[10]

Conservation status[change | change source]

Naked mole rats are not threatened. Despite their tough living conditions, naked mole rats are quite widespread and numerous in the drier regions of East Africa.

References[change | change source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Ross Piper (2007). Extraordinary animals: an encyclopedia of curious and unusual animals. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-33922-6.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Dawkins, Richard (1976). The Selfish Gene. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-286092-5.

- ↑ Counting mole-rat mammaries and hungry pups, biologists explain why naked rodents break the rules, Roger Segelken, Cornell News, August 9, 1999

- ↑ Buffenstein R, Jarvis JU (May 2002). "The naked mole rat—a new record for the oldest living rodent". Sci Aging Knowledge Environ. 2002 (21): pe7. doi:10.1126/sageke.2002.21.pe7. PMID 14602989.[permanent dead link]

- ↑ "Ugly duckling mole rats might hold key to longevity". Sciencedaily.com. 2007-10-16. Retrieved 2009-03-11.

- ↑ "Proposal to sequence an organism of unique interest for research on aging: Heterocephalus glaber, the naked mole-rat". Genomics.senescence.info. Retrieved 2009-04-30.

- ↑ "The Naked Mole Rat Genome Resource: facilitating analyses of cancer and longevity-related adaptations". Bioinformatics. 30 (24): 3558–60. 2014. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btu579. PMC 4253829. PMID 25172923.

{{cite journal}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ↑ Yu, Chuanfei; Li, Yang; Holmes, Andrew; Szafranski, Karol; Faulkes, Chris G.; Coen, Clive W.; Buffenstein, Rochelle; Platzer, Matthias; De Magalhães, João Pedro; Church, George M. (2011). "RNA sequencing reveals differential expression of mitochondrial and oxidation reduction genes in the long-lived naked mole-rat when compared to mice". PLOS ONE. 6 (11): e26729. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...626729Y. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0026729. PMC 3207814. PMID 22073188.

- ↑ MacRae S.L.; et al. (2015). "DNA repair in species with extreme lifespan differences". Aging. 7 (12): 1171–84. doi:10.18632/aging.100866. PMC 4712340. PMID 26729707.

- ↑ Bernstein H. et al 2008. Cancer and aging as consequences of un-repaired DNA damage. In: New Research on DNA Damages (Editors: Honoka Kimura and Aoi Suzuki) Nova Science Publishers, Inc., New York, Chapter 1, pp. 1-47. open access, but read only https://www.novapublishers.com/catalog/product_info.php?products_id=43247 Archived 2014-10-25 at the Wayback Machine ISBN 1604565810

Other websites[change | change source]

- Page on the Animal Diversity Web

- More photos Archived 2009-06-21 at the Wayback Machine

- Heterocephalus glaber images at bioimages.vanderbilt.edu Archived 2009-01-15 at the Wayback Machine

- Naked mole-rat webcam