Pan (genus)

| Pan[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Members of the genus Pan: chimpanzee (left) and bonobo (right) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Hominidae |

| Subfamily: | Homininae |

| Tribe: | Hominini |

| Subtribe: | Panina |

| Genus: | Pan Oken, 1816 |

| Type species | |

| Simia troglodytes = Pan troglodytes | |

| Species | |

| |

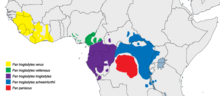

| Distribution of Pan troglodytes (common chimpanzee) and Pan paniscus (bonobo, in red) | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Troglodytes E. Geoffroy, 1812 (preoccupied) | |

The genus Pan is made up of two living species: the chimpanzee and the bonobo. Taxonomically, these two ape species are called panins;[3][4] however, both species are more commonly called chimpanzees or chimps. Together with gorillas, orangutans and humans, they are part of the family Hominidae.

Taxonomy[change | change source]

- Genus Pan: Chimpanzees

- Common chimpanzee, Pan troglodytes

- Bonobo or Pygmy chimpanzee, Pan paniscus

Habitat[change | change source]

The common chimpanzee lives in West and Central Africa. The bonobo lives in the rain forests of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The two species are on opposite sides of the Congo River.

Life and description[change | change source]

Chimpanzees mainly eat fruit, leaves, flowers, seeds, bark, honey, insects, bird eggs, and meat. They spend a lot of time with other chimpanzees from their group, acting up, playing, and chatting. Sometimes they will groom each other; combing and looking through each other's thick fur; picking out the dirt and insects. Grooming helps chimps feel comfortable and friendly.

Chimpanzees can walk on two feet, but they prefer to move about on all four legs. On the ground, they walk on their hind feet and knuckles.[5][6][7] They have hands that look like human hands, but their thumbs are shorter than those of humans. At night, chimpanzees sleep in nests that they make on tree branches. They bend twigs and tuck in leaves to make a soft platform to rest in a place that is safe from enemies on the ground. The gestation period of chimpanzees lasts between six and eight months. Usually only one offspring is produced; they rarely have twins. Chimpanzees live up to 60 years in the wild.[8]

Jane Goodall has studied chimpanzees since 1960. She observed how chimpanzees use tools in several ways. They will pick up rocks to crack nuts for a meal. They also strip down twigs and stick them into a termite mound to collect a tasty snack. Some have been known to make a sponge from leaves in order to hold more drinking water. The chimp chews leaves to soften them up, dips them in rainwater, and then squeezes the water into its mouth. Chimpanzees are also known to think ahead and solve problems.[9][10]

Chimpanzee aggression[change | change source]

The behavior described in this section refers to the common chimpanzee. At present there is no evidence that the bonobo has a similar level of aggressive behavior.

Attacking monkeys[change | change source]

Chimpanzees attack Colobus monkeys by working as a team to corner them in the high branches of the trees. Then they tear the monkey apart and eat it.[11] It is thought the main benefit is that meat is a more rich source of nutrition than their usual vegetarian diet.

- "Goodall’s Gombe data have also led researchers to take a closer look at the role that hunting plays in chimp feeding habits. One recent Gombe study, for instance, concluded that the 45 members of one troop ate a ton of monkey meat per year. During one hunting binge, chimps killed 71 colobus monkeys in 68 days; one chimp alone killed 42 monkeys over five years. All told, chimps may kill and eat a third of the Gombe’s colobus population each year. Researchers have also found that lower-ranking males often trade the meat for mating privileges; such trades may help prevent inbreeding".[11] Otherwise one or two males might father most of a troop’s children.

Attacking other chimpanzee groups[change | change source]

If they can, male chimpanzees try to kill the male members of neighboring groups. Males work together when they spot a chance to make a lightning raid on an isolated male from the other group. They kill him. In Gombe, Tanzania, a group in the 1970s was seen to kill seven of their neighbors one by one, until all were gone. It can take years for this to happen but, when it does, the remaining females and the neighboring territory are added to the now larger group. Attacks like this are carefully planned, done only when success is likely, and carried out in silence.

The advantage for the males that triumph is to breed more children. Their tribe also holds a larger territory, and so has access to more food.[12] Several authors have drawn a connection between this behaviour and the origins of human warfare.[13][14][15]

Scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology studied chimpanzees in Taï National Park in Côte d’Ivoire. The project followed four groups of chimpanzees for twenty years. They found that female chimpanzees patrolled territory and fought with chimpanzees from other groups too, not just males. The scientists wondered if human beings have been imagining that male chimpanzees do all the fighting because we think of human warfare being done mostly by men.[16][17][18]

- One of the scientists, Catherine Crockford, said: "We are now accumulating compelling evidence that cooperation among non-related individuals, and among males and females, has likely been under selection due to the competition between neighboring groups. These findings have therefore strong implications to understand the evolution of cooperation in social species and in humans in particular. Continuous and long-lasting research and conservation efforts are necessary if we want to understand the interplay between competition and cooperation in this emblematic species for human evolution, and how it relates to our own evolution."[16]

Communication[change | change source]

Chimpanzees show their emotions with their faces and sounds. They make hooting sounds to express the discovery of food, and the face of a chimpanzee with a scowling face and lips pressed is to express annoyance. This means the chimpanzee may attack. Or, the chimpanzee may bare its teeth to express that it is afraid or that a more dominant chimp is approaching.[8]p74/5

Relationship with humans[change | change source]

According to a genome study done by the Chimpanzee Sequencing and Analysis Consortium, humans share either 96% or 95% of their DNA with chimpanzees. However, this applies only to single nucleotide polymorphisms, that is, changes in single base pairs only. The full picture is rather different.

24% of the chimpanzee genome does not align with the human genome, and so cannot be directly compared. There are 3% further alignment gaps, 1.23% SNP differences, and 2.7% copy number variations totaling at least 30% differences between chimpanzee and Homo sapiens genomes. On the other hand, 30% of all human proteins are identical in sequence to the corresponding chimpanzee proteins.[19]

Related pages[change | change source]

References[change | change source]

- ↑ Groves, Colin (2005). Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 182–3. ISBN 0-801-88221-4.

- ↑ Bernard Wood et alii, Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Human Evolution, June 2013 (single-volume paperback version of the original 2011 2-volume edition), 1056 pp.; ISBN 978-1-1186-5099-8

- ↑ Muehlenbein, M. P. (2015). Basics in Human Evolution. Elsevier Science. pp. 114–115. ISBN 9780128026526.

- ↑ "Bonobo anatomy reveals stasis and mosaicism in chimpanzee evolution, and supports bonobos as the most appropriate extant model for the common ancestor of chimpanzees and humans". nature.com. April 4, 2017. Retrieved January 10, 2019.

- ↑ Henry Gee (March 23, 2000). "These fists were made for walking". Nature. Retrieved July 8, 2020.

- ↑ "Why aren't humans 'knuckle-walkers'?". The Daily. April 9, 2018. Retrieved July 7, 2020.

- ↑ Caley M Orr (2005). "Knuckle-walking Anteater: A Convergence Test of Adaptation for Purported Knuckle-Walking Features of African Hominidae". Am J Phys Anthropol. 128 (3): 639–58. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20192. PMID 15861420. Retrieved July 8, 2020.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Pous, Dinorah (2003). Blue Planet English through Science level 5. Alpha Omega Publications. ISBN 970-10-3769-3.

- ↑ Köhler, Wolfgang 1925. The mentality of apes, transl. from the 2nd German edition by Ella Winter. Kegan, Trench: London and Harcourt, Brace and World: New York. Original was Intelligenzprüfungen an Anthropoiden, Berlin 1917.

- ↑ The Jane Goodall Institute: "Chimpanzee Central", 2008.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "Jane Goodall's Wild Chimpanzees". PBS. 1996. Retrieved 2010-07-28.

- ↑ Mitani J.C; Watts D.P. & Amsler S.J. 2010. Lethal intergroup aggression leads to territorial expansion in wild chimpanzees. Current Biology 20 (12) R507/8.

- ↑ Wrangham R. & Peterson D. 1996. Demonic males: apes and the origins of human warfare. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- ↑ Wrangham R. 2006. Why apes and humans kill. In Jones M. & Fabian A. (eds) Conflict. Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Trivers, Robert 2011. Deceit and self-deception: fooling yourself the better to fool others. London: Penguin, p249/250: Chimpanzee raiding > human warfare. ISBN 978-0-141-01991-8

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology (May 27, 2020). "In chimpanzees, females contribute to the protection of the territory" (Press release). Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- ↑ Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology (May 27, 2020). "In chimpanzees, females contribute to the protection of the territory" (Press release). Eurekalert. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- ↑ Sylvia Lemoine; Christophe Boesch; Anna Preis; Liran Samuni; Catherine Crockford; Roman M. Wittig (May 27, 2020). "Group dominance increases territory size and reduces neighbour pressure in wild chimpanzees". Royal Society Open Science. 7 (5): 200577. Bibcode:2020RSOS....700577L. doi:10.1098/rsos.200577. PMC 7277268. PMID 32537232.

- ↑ The Chimpanzee Sequencing and Analysis Consortium (2005). "Initial sequence of the chimpanzee genome and comparison with the human genome". Nature. 437 (1 September 2005): 69–87. Bibcode:2005Natur.437...69.. doi:10.1038/nature04072. PMID 16136131. S2CID 2638825.