Tree of life (biology)

The tree of life is a metaphor which expresses the idea that all life is related by common descent.

Charles Darwin was the first to use this metaphor in modern biology. It had been used many times before for other purposes.

The evolutionary tree shows the relationships among various biological groups. It includes data from DNA, RNA and protein analysis.

Tree of life work is a product of traditional comparative anatomy, and modern molecular evolution and molecular clock research. Below is a simplified version of present-day understanding.

Precursors[change | change source]

Lamarck[change | change source]

Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (1744–1829) produced the first branching tree of animals in his Philosophie Zoologique (1809). It was an upside-down tree starting with worms and ending with mammals. However, Lamarck did not believe in common descent of all life. Instead, he believed that life consists of separate parallel lines advancing from simple to complex.[1]

Hitchcock[change | change source]

The American geologist Edward Hitchcock (1763–1864) published in 1840 the first tree of life based on paleontology in his Elementary Geology.[2] On the vertical axis are paleontological periods. Hitchcock made a separate tree for plants (left) and animals (right). The plant and animal trees are not connected at the bottom of the chart. Furthermore, each tree starts with multiple origins. However, they were not evolutionary trees, because Hitchcock believed that a deity was the agent of change.

Vestiges[change | change source]

The first edition of Robert Chambers' Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation was published anonymously in 1844. It contained a tree-like diagram in the chapter 'Hypothesis of the development of the vegetable and animal kingdoms'. It shows a model of embryological development where fish (F), reptiles (R), and birds (B) represent branches from a path leading to mammals (M).

In the text this branching tree idea is tentatively applied to the history of life on earth: "there may be branching".[3]p191

Darwin's tree of life[change | change source]

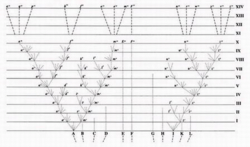

Charles Darwin (1809–1882) was the first to produce an evolutionary tree of life. He was very cautious about the possibility of reconstructing the history of life. In On the Origin of Species (1859) Chapter IV he presented an abstract diagram of a theoretical tree of life for species of an unnamed large genus (see figure).

In Darwin's own words: "Thus, the small differences distinguishing varieties of the same species, will steadily tend to increase till they come to equal the greater differences between species of the same genus, or even of distinct genera."[4]

This is a branching pattern with no names given to species, unlike the more linear tree Ernst Haeckel made years later.

In his summary to the section as revised in the 6th edition of 1872, Darwin explains his views on the Tree of Life:

The affinities of all the beings of the same class have sometimes been represented by a great tree. I believe this simile largely speaks the truth. The green and budding twigs may represent existing species; and those produced during former years may represent the long succession of extinct species...

The limbs divided into great branches, and these into lesser and lesser branches, were themselves once, when the tree was young, budding twigs; and this connection of the former and present buds by ramifying branches may well represent the classification of all extinct and living species in groups subordinate to groups.

Of the many twigs which flourished when the tree was a mere bush, only two or three, now grown into great branches, yet survive and bear the other branches; so with the species which lived during long-past geological periods, very few have left living and modified descendants. From the first growth of the tree, many a limb and branch has decayed and dropped off; and these fallen branches of various sizes may represent those whole orders, families, and genera which have now no living representatives, and which are known to us only in a fossil state.

As we here and there see a thin straggling branch springing from a fork low down in a tree, and which by some chance has been favoured and is still alive on its summit, so we occasionally see an animal like the Ornithorhynchus (Platypus) or Lepidosiren (South American lungfish), which in some small degree connects by its affinities two large branches of life, and which has apparently been saved from fatal competition by having inhabited a protected station.

As buds give rise by growth to fresh buds, and these, if vigorous, branch out and overtop on all sides many a feebler branch, so by generation I believe it has been with the great Tree of Life, which fills with its dead and broken branches the crust of the earth, and covers the surface with its ever-branching and beautiful ramifications.

The tree of life today[change | change source]

The model of a tree is still considered valid for eukaryotic life forms. Research into the earliest branches of the eukaryote tree suggests a tree with either four supergroups,[6][7] or two supergroups.[8] There does not yet appear to be a consensus; in a review article, Roger and Simpson conclude that "with the current pace of change in our understanding of the eukaryote tree of life, we should proceed with caution".[9]

Biologists now recognize that the prokaryotes, the bacteria and archaea have the ability to transfer genetic information between unrelated organisms through horizontal gene transfer (HGT). Recombination, gene loss, duplication, and gene creation are a few of the processes by which genes can be transferred within and between bacterial and archaeal species, causing variation that is not due to vertical transfer.[10][11][12] There is emerging evidence of HGT occurring within the prokaryotes at the single and multicell level and the view is now emerging that the tree of life gives an incomplete picture of life's evolution. It was a useful tool in understanding the basic processes of evolution but cannot explain the full complexity of the situation.[11]

Gallery[change | change source]

Related pages[change | change source]

- Tree of Life disambiguation page

Other websites[change | change source]

- Tree of Life Web Project Archived 2012-09-11 at the Wayback Machine - explore complete phylogenetic tree interactively

- Tree of Life illustration - A modern illustration of the complete tree of life.

- Science Magazine Tree of Life - Sample tree of life from Science journal.

- Science journal issue - Issue devoted to the tree of life.

- [2]-Report on recent paper on "pruning" of the tree of life model.

- The Tree of Life by Garrett Neske, The Wolfram Demonstrations Project: "presents an interactive tree of life that allows you to explore the relationships between many different kinds of organisms by allowing you to select an organism and visualize the clade to which it belongs".

References[change | change source]

- ↑ Peter J. Bowler 2003. Evolution: the history of an idea. 3rd ed, University of California Press. 90-91.

- ↑ J. David Archibald 2009. Edward Hitchcock’s Pre-Darwinian (1840) Tree of Life. Journal of the History of Biology 42:561–592

- ↑ Online Vestiges:online edition of Vestiges

- ↑ Darwin 1859, pp. 116–130

- ↑ Darwin 1872, pp. 104–105

- ↑ Burki, Fabien; Shalchian-Tabrizi, Kamran & Pawlowski, Jan (2008), "Phylogenomics reveals a new 'megagroup' including most photosynthetic eukaryotes", Biology Letters, 4 (4): 366–369, doi:10.1098/rsbl.2008.0224, PMC 2610160, PMID 18522922

- ↑ "Apollon: the Tree of Life has lost a branch". Archived from the original on 2011-10-28. Retrieved 2011-03-07.

- ↑ Kim, E.; Graham, L.E. & Redfield, Rosemary Jeanne (2008), "EEF2 analysis challenges the monophyly of Archaeplastida and Chromalveolata", PLOS ONE, 3 (7): e2621, Bibcode:2008PLoSO...3.2621K, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002621, PMC 2440802, PMID 18612431

- ↑ Roger, A.J. & Simpson, A.G.B. (2009), "Evolution: revisiting the root of the Eukaryote tree", Current Biology, 19 (4): R165–7, doi:10.1016/j.cub.2008.12.032, PMID 19243692, S2CID 13172971

- ↑ Jain R, Rivera MC, Lake JA (1999), "Horizontal gene transfer among genomes: the complexity hypothesis.", Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 96 (7): 3801–6, Bibcode:1999PNAS...96.3801J, doi:10.1073/pnas.96.7.3801, PMC 22375, PMID 10097118.

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ 11.0 11.1 Graham Lawton 2009. Why Darwin was wrong about the tree of life. New Scientist issue 2692 21 January 2009 [1] Accessed Feb 2009

- ↑ Doolittle, W. Ford (February, 2000). Uprooting the tree of life. Scientific American 282 (6): 90–95.