Mughal Empire

Mughal Empire | |

|---|---|

| 1526–1858 | |

The empire at its greatest extent in c. 1700 under Aurangzeb | |

| Capital |

|

| Official languages | |

| Religion | Sunni Islam (Official) |

| Government | Monarchy |

| Emperor[a] | |

• 1526–1530 (first) | Babur |

• 1837–1857 (last) | Bahadur Shah II |

| Vakil-i-Mutlaq | |

• 1526–1540 (first) | Mir Khalifa |

• 1795–1818 (last) | Daulat Rao Sindhia |

| Grand Vizier | |

• 1526–1540 (first) | Mir Khalifa |

• 1775–1797 (last) | Asaf-ud-Daula |

| Establishment | |

• Founding | 1526 |

• Fall | 1858 |

| Area | |

| 1690[5][6] | 4,000,000 km2 (1,500,000 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 1595 | 125,000,000[7] |

• 1700 | 158,000,000[8] |

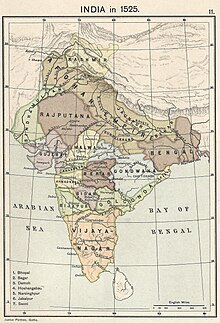

The Mughal Empire (Urdu: مغلیہ سلطنت, Persian: دولتِ مغل), also referred as Hindustan[9] was an Indian Muslim empire [10], in South Asia which existed from 1526 to 1858. When it was biggest it ruled most of the subcontinent, including what is now Pakistan, India, Afghanistan, and Bangladesh.[11] Between 1526 and 1707, It contributed to 24% of the world's GDP[12],It was the world's largest economy and it was well known for having signaled proto-industrialization and for its lavish architecture.[13][14]

The Mughal emperors were Turk-Mongols in origin.[15], Though they later settled in India permanently and got Indianized[10], Considered themselves Hindustanis[16][17] and will continue living in india even after the British conquest of the Mughal empire in 1858. Babur of the Timurid dynasty founded the Mughal Empire (and Mughal dynasty) in 1526 and ruled until 1530. He was followed by Humayun (1530-1540) and (1555-1556), Akbar (1556-1605), Jahangir (1605-1627), Shah Jahan (1628-1658), and Aurangzeb (1658-1707) and several other minor rulers until Bahadur Shah Zafar II (1837-1857). After the death of Aurangzeb, the Mughal Empire became weak. It continued until 1857-58. By that time, South Asia had become under the British Raj.

The Mughal Empire was established by able Muslim rulers who came from the present-day Uzbekistan after defeating the Delhi sultanate. The Mughal rule in South Asia saw the region into a united indian state[18]. Which was being administered under one single powerful ruler, Such unification was not seen since the era of Delhi Sultanate, Guptas and Mauryans. During the Mughal period, art and architecture flourished and many beautiful monuments were constructed. The rulers were skillful warriors and admirers of art as well.[19]

Name[change | change source]

The closest to an official name for the empire was Hindustan, which was documented in the Ain-i-Akbari.[9] Mughal administrative records also refer to the empire as "dominion of Hindustan" (Wilāyat-i-Hindustān),[20] "country of Hind" (Bilād-i-Hind), or "Sultanate of Al-Hind" (Salṭanat(i) al-Hindīyyah) as observed in the epithet of emperor Aurangzeb.[21] Contemporary chronicles from Qing China referred to the empire as Hindustan (Héndūsītǎn).[22] In the west, the term "Mughal" was used for the emperor, and by extension, the empire as a whole.[23]

The Mughal designation for their own dynasty was Gurkani (Gūrkāniyān), a reference to their descent from the Turco-Mongol conqueror Timur, who took the title Gūrkān 'son-in-law' after his marriage to a Chinggisid princess.[24] The word Mughal (also spelled Mogul[25] or Moghul in English) is the Indo-Persian form of Mongol. The Mughal dynasty's early followers were Chagatai Turks, and not mongols.[26] although the dynasty claimed descent from Genghis Khan.[27] The term Mughal was applied to them in India by association with the Mongols and to distinguish them from the local Indian and Afghan elite which ruled the Delhi Sultanate.[26] The term gained currency during the 19th century, but remains disputed by Indologists.[28] In Marshall Hodgson's view, the dynasty should be called Timurid/Timuri or Indo-Timuri.[26]

History[change | change source]

Babur and Humayun (1526–1556)[change | change source]

The Mughal Empire was founded by Babur (reigned 1526–1530), a Central Asian ruler who was descended from the Turco-Mongol conqueror Timur (the founder of the Timurid Empire) on his father's side, and from Genghis Khan on his mother's side.[29] Paternally, Babur belonged to the Turkicized Barlas tribe of Mongol origin.[30] Ousted from his ancestral domains in Central Asia, Babur turned to India to satisfy his ambitions.[31] He established himself in Kabul and then pushed steadily southward into India from Afghanistan through the Khyber Pass.[29] Babur's forces defeated Ibrahim Lodi in the First Battle of Panipat in 1526. Before the battle, Babur sought divine favour by abjuring liquor, breaking the wine vessels and pouring the wine down a well. However, by this time Lodi's empire was already crumbling, and it was the Rajput Confederacy which was the strongest power of Northern India under the capable rule of Rana Sanga of Mewar. He defeated Babur in the Battle of Bayana.[32] However, in the decisive Battle of Khanwa which was fought near Agra, the Timurid forces of Babur defeated the Rajput army of Sanga. This battle was one of the most decisive and historic battles in Indian history, as it sealed the fate of Northern India for the next two centuries.

After the battle, the centre of Mughal power became Agra instead of Kabul. The preoccupation with wars and military campaigns, however, did not allow the new emperor to consolidate the gains he had made in India.[33] The instability of the empire became evident under his son, Humayun (reigned 1530–1556), who was forced into exile in Persia by rebels. The Sur Empire (1540–1555), founded by Sher Shah Suri (reigned 1540–1545), briefly interrupted Mughal rule.[29] Humayun's exile in Persia established diplomatic ties between the Safavid and Mughal Courts, and led to increasing Persian cultural influence in the later restored Mughal Empire.[source?] Humayun's triumphant return from Persia in 1555 restored Mughal rule in some parts of India, but he died in an accident the next year.[29]

Akbar to Aurangzeb (1556–1707)[change | change source]

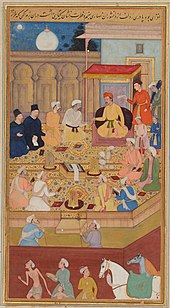

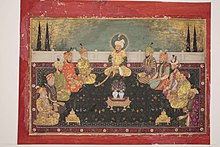

Akbar (reigned 1556–1605) was born Jalal-ud-din Muhammad[34] in the Rajput Umarkot Fort,[35] to Humayun and his wife Hamida Banu Begum, a Persian princess.[36] Akbar succeeded to the throne under a regent, Bairam Khan, who helped consolidate the Mughal Empire in India. Through warfare and diplomacy, Akbar was able to extend the empire in all directions and controlled almost the entire Indian subcontinent north of the Godavari River.[source?] He created a new ruling elite loyal to him, implemented a modern administration, and encouraged cultural developments. He increased trade with European trading companies.[29] India developed a strong and stable economy, leading to commercial expansion and economic development.[source?] Akbar allowed freedom of religion at his court and attempted to resolve socio-political and cultural differences in his empire by establishing a new religion, Din-i-Ilahi, with strong characteristics of a ruler cult.[29] He left his son an internally stable state, which was in the midst of its golden age, but before long signs of political weakness would emerge.[29]

Jahangir (born Salim,[37] reigned 1605–1627) was born to Akbar and his wife Mariam-uz-Zamani, an Indian Rajput princess.[38] Salim was named after the Indian Sufi saint, Salim Chishti.[39][40] He "was addicted to opium, neglected the affairs of the state, and came under the influence of rival court cliques".[29] Jahangir distinguished himself from Akbar by making substantial efforts to gain the support of the Islamic religious establishment. One way he did this was by bestowing many more madad-i-ma'ash (tax-free personal land revenue grants given to religiously learned or spiritually worthy individuals) than Akbar had.[41] In contrast to Akbar, Jahangir came into conflict with non-Muslim religious leaders, notably the Sikh guru Arjan, whose execution was the first of many conflicts between the Mughal empire and the Sikh community.[42][43][44]

Shah Jahan (reigned 1628–1658) was born to Jahangir and his wife Jagat Gosain, a Rajput princess.[37] His reign ushered in the golden age of Mughal architecture.[45] During the reign of Shah Jahan, the splendour of the Mughal court reached its peak, as exemplified by the Taj Mahal. The cost of maintaining the court, however, began to exceed the revenue coming in.[29] His reign was called as "The Golden Age of Mughal Architecture". Shah Jahan extended the Mughal empire to the Deccan by ending the Nizam Shahi dynasty and forcing the Adil Shahis and Qutb Shahis to pay tribute.[46]

Shah Jahan's eldest son, the liberal Dara Shikoh, became regent in 1658, as a result of his father's illness.[source?] Dara championed a syncretistic Hindu-Muslim culture, emulating his great-grandfather Akbar.[47] With the support of the Islamic orthodoxy, however, a younger son of Shah Jahan, Aurangzeb (r. 1658–1707), seized the throne. Aurangzeb defeated Dara in 1659 and had him executed.[29] Although Shah Jahan fully recovered from his illness, Aurangzeb kept Shah Jahan imprisoned until he died in 1666.[48]: 68 Aurangzeb oversaw an increase in the Islamicization of the Mughal state. He encouraged conversion to Islam, reinstated the jizya on non-Muslims, and compiled the Fatawa 'Alamgiri, a collection of Islamic law. Aurangzeb also ordered the execution of the Sikh guru Tegh Bahadur, leading to the militarization of the Sikh community.[49][43][44] From the imperial perspective, conversion to Islam integrated local elites into the king's vision of network of shared identity that would join disparate groups throughout the empire in obedience to the Mughal emperor.[50] His campaign to conquer South and Western India nominally increased the size of Mughal Empire but had a ruinous effect on Mughal Empire.[51] This campaign also had a ruinous effect on Mughal Treasury, and Emperor's absence led to a severe decline in Governance in Northern India. Marathas started expanding northwards shortly after the death of Aurangzeb, defeated the Mughals in Delhi and Bhopal, and extended their empire up to Battle of Peshawar.

Notes[change | change source]

References[change | change source]

- ↑ Sinopoli, Carla M. (1994). "Monumentality and Mobility in Mughal Capitals". Asian Perspectives. 33 (2): 294. ISSN 0066-8435. JSTOR 42928323. Archived from the original on 1 May 2022. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ↑ Conan 2007, p. 235.

- ↑ "Islam: Mughal Empire (1500s, 1600s)". BBC. 7 September 2009. Archived from the original on 13 August 2018. Retrieved 13 June 2019.

- ↑ Morier 1812, p. 601.

- ↑ Turchin, Peter; Adams, Jonathan M.; Hall, Thomas D. (2006). "East–West Orientation of Historical Empires and Modern States". Journal of World-Systems Research. 12 (2): 219–229. doi:10.5195/JWSR.2006.369. ISSN 1076-156X.

- ↑ Rein Taagepera (September 1997). "Expansion and Contraction Patterns of Large Polities: Context for Russia". International Studies Quarterly. 41 (3): 475–504. doi:10.1111/0020-8833.00053. JSTOR 2600793. Archived from the original on 19 November 2018. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

- ↑ Dyson, Tim (2018). A Population History of India: From the First Modern People to the Present Day. Oxford University Press. pp. 70–71. ISBN 978-0-19-256430-6.

We have seen that there is considerable uncertainty about the size of India's population c.1595. Serious assessments vary from 116 to 145 million (with an average of 125 million). However, the true figure could even be outside of this range. Accordingly, while it seems likely that the population grew over the course of the seventeenth century, it is unlikely that we will ever have a good idea of its size in 1707.

- ↑ Cite error: The named reference

boroczwas used but no text was provided for refs named (see the help page). - ↑ 9.0 9.1 Vanina, Eugenia (2012). Medieval Indian Mindscapes: Space, Time, Society, Man. Primus Books. p. 47. ISBN 978-93-80607-19-1. Archived from the original on 22 September 2023. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Richards, John F. (1995), The Mughal Empire, Cambridge University Press, p. 2, ISBN 978-0-521-56603-2, archived from the original on 22 September 2023, retrieved 9 August 2017 Quote: "Although the first two Timurid emperors and many of their noblemen were recent migrants to the subcontinent, the dynasty and the empire itself became indisputably Indian. The interests and futures of all concerned were in India, not in ancestral homelands in the Middle East or Central Asia. Furthermore, the Mughal Empire emerged from the Indian historical experience. It was the end product of a millennium of Muslim conquest, colonization, and state-building in the Indian subcontinent."

- ↑ Stein, Burton (2010), A History of India, John Wiley & Sons, pp. 159–, ISBN 978-1-4443-2351-1, archived from the original on 22 September 2023, retrieved 15 July 2019 Quote: "The realm so defined and governed was a vast territory of some 750,000 square miles [1,900,000 km2], ranging from the frontier with Central Asia in northern Afghanistan to the northern uplands of the Deccan plateau, and from the Indus basin on the west to the Assamese highlands in the east."

- ↑ Jeffrey G. Williamson & David Clingingsmith, India's Deindustrialization in the 18th and 19th Centuries Archived 29 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Global Economic History Network, London School of Economics

- ↑ Cite error: The named reference

Maddison2003was used but no text was provided for refs named (see the help page). - ↑ Cite error: The named reference

vosswas used but no text was provided for refs named (see the help page). - ↑ Richards, John F. (1995), The Mughal Empire, Cambridge University Press, p. 6, ISBN 978-0-521-56603-2

- ↑ Chandra, Satish (1959). Parties And Politics At The Mughal Court.

- ↑ Vanina, Eugenia (2012). Medieval Indian Mindscapes: Space, Time, Society, Man. Primus Books. p. 47. ISBN 978-93-80607-19-1 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Britanica, Encyclopaedia (2024), The Mughal dynasty, Britanica, p. 6, ISBN 978-0-521-56603-2

- ↑ Asher, Catherine B.; Talbot, Cynthia (2006), India Before Europe, Cambridge University Press, pp. 186–, ISBN 978-0-521-80904-7, archived from the original on 22 September 2023, retrieved 15 July 2019 Quote: "All these factors resulted in greater patronage of the arts, including textiles, paintings, architecture, jewellery, and weapons to meet the ceremonial requirements of kings and princes."

- ↑ Hardy, P. (1979). "Modern European and Muslim Explanations of Conversion to Islam in South Asia: A Preliminary Survey of the Literature". In Levtzion, Nehemia (ed.). Conversion to Islam. Holmes & Meier. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-8419-0343-2. Archived from the original on 3 April 2023. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- ↑ "Name of the Monument/ site: Tomb of Aurangzeb" (PDF). asiaurangabad.in. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015.

- ↑ Mosca, Matthew (2013-02-20). From Frontier Policy to Foreign Policy: The Question of India and the Transformation of Geopolitics in Qing China. Stanford University Press. pp. 78–94. ISBN 978-0-8047-8538-9. Archived from the original on 7 November 2023. Retrieved 7 November 2023.

- ↑ Fontana, Michela (2011). Matteo Ricci: A Jesuit in the Ming Court. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-4422-0588-8. Archived from the original on 22 September 2023. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ↑ Zahir ud-Din Mohammad (2002). Thackston, Wheeler M. (ed.). The Baburnama: Memoirs of Babur, Prince and Emperor. New York: Modern Library. p. xlvi. ISBN 978-0-375-76137-9.

In India the dynasty always called itself Gurkani, after Temür's title Gurkân, the Persianized form of the Mongolian kürägän, 'son-in-law,' a title he assumed after his marriage to a Genghisid princess.

- ↑ John Walbridge. God and Logic in Islam: The Caliphate of Reason. p. 165.

Persianate Mogul Empire.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Hodgson, Marshall G. S. (2009). The Venture of Islam. Vol. 3. University of Chicago Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-226-34688-5.

- ↑ Canfield, Robert L. (2002). Turko-Persia in Historical Perspective. Cambridge University Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-521-52291-5.

- ↑ Huskin, Frans Husken; Dick van der Meij (2004). Reading Asia: New Research in Asian Studies. Routledge. p. 104. ISBN 978-1-136-84377-8.

- ↑ 29.00 29.01 29.02 29.03 29.04 29.05 29.06 29.07 29.08 29.09 Berndl, Klaus (2005). National Geographic Visual History of the World. National Geographic Society. pp. 318–320. ISBN 978-0-7922-3695-5.

- ↑ Gérard Chaliand, A Global History of War: From Assyria to the Twenty-First Century, University of California Press, California 2014, p. 151

- ↑ Bayley, Christopher. The European Emergence. The Mughals Ascendant. p. 151. ISBN 0-7054-0982-1.

- ↑ Hooja, Rima (2006). A History of Rajasthan. Rupa. p. 454. ISBN 978-81-291-1501-0. Archived from the original on 22 September 2023. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

From Babur's memoirs we learn that Sanga's successes against the Mughal advance guard commanded by Abdul Aziz, and other forces at Bayana, ... severely demoralised the fighting spirit of Babur's troops encamped near Sikri.

- ↑ Bayley, Christopher. The European Emergence. The Mughals Ascendant. p. 154. ISBN 0-7054-0982-1.

- ↑ Ballhatchet, Kenneth A. "Akbar". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 25 May 2023. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- ↑ Smith, Vincent Arthur (1917). Akbar the Great Mogul, 1542–1605. Oxford at The Clarendon Press. pp. 13–14.

- ↑ Begum, Gulbadan (1902). The History of Humāyūn (Humāyūn-Nāma). Translated by Beveridge, Annette S. Royal Asiatic Society. pp. 237–239.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Mohammada, Malika (2007). The Foundations of the Composite Culture in India. Aakar Books. p. 300. ISBN 978-81-89833-18-3.

- ↑ Gilbert, Marc Jason (2017). South Asia in World History. Oxford University Press. p. 79. ISBN 978-0-19-976034-3. Archived from the original on 22 September 2023. Retrieved 22 August 2017.

- ↑ Muhammad-Hadi (1999). Preface to The Jahangirnama. Translated by Thackston, Wheeler M. Oxford University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-19-512718-8.

- ↑ Jahangir, Emperor of Hindustan (1999). The Jahangirnama: Memoirs of Jahangir, Emperor of India. Translated by Thackston, Wheeler M. Oxford University Press. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-19-512718-8.

- ↑ Faruqui, Munis D. (2012). The Princes of the Mughal Empire, 1504–1719. Cambridge University Press. pp. 268–269. ISBN 978-1-107-02217-1.

- ↑ Robb, Peter (2011), A History of India, Macmillan International Higher Education, pp. 97–98, ISBN 978-0-230-34424-2

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Asher, Catherine B.; Talbot, Cynthia (2006). India before Europe. Cambridge University Press. p. 267. ISBN 0-521-80904-5. OCLC 61303480.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 "BBC – Religions – Sikhism: Origins of Sikhism". BBC. 30 September 2009. Archived from the original on 17 August 2018. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- ↑ Mehta, Jaswant Lal (1984) [First published 1981]. Advanced Study in the History of Medieval India. Vol. II (2nd ed.). Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd. p. 59. ISBN 978-81-207-1015-3. OCLC 1008395679.

- ↑ Singhal, Damodar P. (1983). A History of the Indian People. Methuen. p. 193. ISBN 978-0-413-48730-8. Archived from the original on 22 September 2023. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

- ↑ Dara Shikoh Archived 3 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia, by Josef W. Meri, Jere L Bacharach. Routledge, 2005. ISBN 0-415-96690-6. Page 195-196.

- ↑ Cite error: The named reference

Truschkewas used but no text was provided for refs named (see the help page). - ↑ Robb, Peter (2011). A History of India. Macmillan International Higher Education. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-230-34424-2.

- ↑ Abhishek Kaicker (2020). The King and the People: Sovereignty and Popular Politics in Mughal Delhi. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-007067-0. Archived from the original on 3 April 2023. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- ↑ Sarkar Jadunath (1928). A Short History Of Aurangzib.