Christchurch mosque shootings

| Christchurch mosque shootings | |

|---|---|

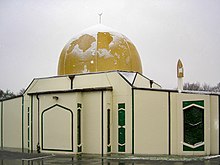

The Al Noor Mosque in August 2019 | |

| Location | Christchurch, Canterbury, New Zealand |

| Coordinates | |

| Date | 15 March 2019 1:40 – 1:59 p.m. (NZDT; UTC+13) |

| Target | Muslim worshippers |

Attack type | Mass shooting,[1] terrorist attack,[2] shooting spree, mass murder, right-wing terrorism, hate crime |

| Weapons |

|

| Deaths | 51[a] |

Injured | 40 |

| Perpetrator | Brenton Tarrant |

| Motive | |

| Verdict | Pleaded guilty to all charges |

| Convictions | 51 counts of murder 40 counts of attempted murder One count of committing a terrorist act |

| Sentence | 52 life sentences without the chance for parole, plus 480 years[8] |

The Christchurch mosque shootings were two terrorist mass shootings at two mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand on 15 March 2019. They were committed by Brenton Tarrant who entered the two mosques during Friday prayer, firstly at the Al Noor Mosque where he murdered 44 people and wounded 35 others and later at the Linwood Islamic Centre where 7 were killed and 5 were wounded, in total 51 Muslim worshippers were killed and 40 were wounded.

Tarrant was arrested after his vehicle was rammed by a police car when he was driving to a third mosque in Ashburton. He live-streamed the first shooting on Facebook and had published a 74-page manifesto titled The Great Replacement online before the attack. On 26 March 2020, he pled guilty[9][10] to 51 murders, 40 attempted murders, and engaging in a terrorist act,[11][12] and in August was sentenced to 52 life sentences without the possibility of parole plus 480 years – the first sentence of that kind in New Zealand.[8][13][14]

The attacks were mainly motivated by white nationalist and anti-immigration beliefs. Tarrant called himself as a fascist and supported the far-right Great Replacement conspiracy theory and for all non-European immigrants to be removed from countries that he considered culturally and ethnically European.

Perpetrator[change | change source]

Brenton Harrison Tarrant, a white Australian man was born on 27 October, 1990 and grew up in Grafton, New South Wales, was 28-years old when he committed the attacks.[15] He attended Grafton High School.[16]

Tarrant had a troubled childhood, starting when his parents seperated, his grandfather died and their family home was burnt down in a fire.[17] These events traumatized him and left him with social anxiety disorder, which likely worsened when his mother's new parter assaulted him, his sister and mother.[17] He began to gain weight from age 12, because of this he started getting bullied at school, where he also had few friends. He was unfocused at school but also strangely familiar with topics like the World War II. Tarrant showed signs of racism and worries about immigration as young as 12 years old. He frequently made racist comments about his mother's former partner's Indigenous Australian heritage, which worried his high school teachers.[18]

Tarrant began using 4chan at the age of 14, a site known for sharing extremist content, and start obsessively excercising to lose weight. In 2009, Tarrant qualified as a personal trainer at Big River Gym in Grafton. The next year, he found his father dead by suicide, following this he inherited A$457,000 from his father, he stopped working as a personal trainer and used the money to invest and travel across the world.

Travels and connections to far-right groups[change | change source]

Starting in 2012, he went to several countries, always alone except for a visit to North Korea where he was required to travel with a tour guide and other visitors. In March 2013, he travelled to New Zealand for a vacation, where he stayed with a friend for three days for gaming. The friend and his parents were gun users. They took Tarrant to a shooting club where he had his first experience with guns.[19]

Police in Bulgaria and Turkey investigated Tarrant's visits to their countries.[20][21][22] Security officials suspected that he went into contact with far-right organisations about two years before the shootings, while visiting European nations.[23] He donated €1,500 to Identitäre Bewegung Österreich, an Austrian Identitarian movement organization in Europe, and also €2,200 to Génération Identitaire, the French branch of the group, and spoke with group leader Martin Sellner using e-mail in January 2018 and July 2018, hoping to meet Tarrant in Vienna and a linking to his YouTube channel.[24] When he was preparing the attacks, Tarrant made a donation of $106.68 to Rebel Media, a site that showed both Sellner and several articles discussing the "white genocide" and "Great Replacement" conspiracy theories.[25]

In 2016, three years prior to the attacks, Tarrant praised Blair Cottrell as a leader of the far-right movements in Australia and left more than 30 comments on the now-deleted "United Patriots Front" and "True Blue Crew" websites.[26] A Melbourne man said that in 2016, he filed a police complaint after Tarrant told him in an online conversation, "I hope one day you meet the rope". He said that the police told him to block Tarrant. The police said that they didn't find a complaint.[27] Tarrant told investigators that he frequented right-wing discussion boards on 4chan and 8chan and also found YouTube to be "a significant source of information and inspiration."[28]

Interested in locations of battles between Christian European nations and the Ottoman Empire, Tarrant went on another series of visits to the Balkans from 2016 to 2018, with Croatia, Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary, Turkey, and Bosnia-Herzegovina.[29][30] He posted Balkan nationalist material on social media platforms[31] and called for the United States to be weakened to prevent what he saw as NATO intervention in support of Muslims against Christians.[32][30][33] He said he was against intervention by NATO because he saw the Serbian military as "Christian Europeans attempting to remove these Islamic occupiers from Europe".[32][33] By June 2016, his family saw a change in Tarrant's personality, which he said was the result of a mugging incident in Ethiopia, and his mother was worrying for his mental health.[34]

Settlement in New Zealand[change | change source]

Tarrant moved to New Zealand in August 2017 and lived in Andersons Bay in Dunedin until the shootings.[35][36][37] A neighbour described him as a friendly loner.[38] He was a member of a gun club in southern Otago, where he practised shooting at its range.[39][40] In 2018, Tarrant was treated for eye and thigh injuries at Dunedin Hospital; he told doctors he got the injuries when he tried to remove an improperly chambered bullet from a gun. The doctors also treated him for steroid abuse, but never reported Tarrant's visit to the authorities,[36] which would have led in police rechecking his health to ha,' a gun licence.[41]

When living in Dunedin, Tarrant had no job and bought neccessities and preparations for the terrorist attack using the money he received from his father and income from investments. When asked, he gave no explanation for his future plans once he ran out of money other than mentioning to his sister the possibility of suicide and later telling family members and gaming friends that he planned to move to Ukraine.[42] Tarrant believed he would run out of his money by August 2019. A document, dated January 2019, was discovered which he wrote "March is go do rain or shine [sic]".[43]

Planning[change | change source]

In 2016 and 2017, Tarrant is believed to have become obsessed with terrorist attacks committed by Islamic extremists and he started planning his own attacks in 2017 then chose the Al Noor Mosque and Linwood Islamic Centre as targets in Decemer 2018, along with a third mosque in Ashburton which he got arrested before being able to go to during the attacks.[44] Some survivors at the Al Noor Mosque said they saw Tarrant there on Friday prayers before the attack, pretending to pray and asking about the mosque's schedules.[45] The Royal Commission report found no evidence of this,[46] and police said that Tarrant had instead looked at an online tour of the mosque as part of his planning.[47]

On 8 January 2019, Tarrant used a drone from a nearby park to look at the outside of the mosque.[48] He used the internet to find pictures of the inside and prayer schedules to figure out when the mosques would have the most people.[49] On the same day, he drove past the Linwood Islamic Centre.[48]

Weaponry[change | change source]

Police found six guns after the shootings: two AR-15 style rifles, two 12-gauge shotguns, a lever-action rifle and bolt-action rifle. Tarrant was granted a gun licence in November 2017,[50][51] and he bought weapons between December 2017 and March 2019, along with more than 7,000 rounds of ammunition.[52] According to a gun shop, Tarrant bought four guns and ammunition online.

[53] The shop said they did not see anything strange about him.[54] He used four 30-round magazines, five 40-round magazines, and one 60-round magazine in the shootings.[55] He illegally used higher capacity magazines which went against the rules of Tarrant's gun license.[56][57][58] He spent an estimated NZ$30,000 on gun products.[59]

The guns and magazines used were covered in the names of battles and people from history, battles between Christian nations and Islamic nations,[60][61][62][63] as well as the names of recent Islamic terrorist attack victims and the names of similar attackers likw Alexandre Bissonnette, Luca Traini, Anton Lundin-Pettersson Darren Osbourne.[64][65] Other words written on the gun include "Turkofagos" (Greek: Τουρκοφάγος, lit. 'Turk-eater';[66] this was the nickname of Nikitas Stamatelopoulos during battles in the Greek War of Independence[67]), far-right slogans such as the anti-Muslim phrase "Remove Kebab" that comes from Serbia and the Fourteen Words.[60][62][63] The Archangel Michael's Cross used by the Romanian fascist organisation Iron Guard was one the symbols on the gun.[68]

On his armoured vest was a Black Sun patch[69] and two dog tags: one with a Celtic cross, and one with a Kolovrat design.[70] His armoured vest had seven loaded .223 magazines in the front pockets.[71] He also wore an airsoft helmet with a GoPro camera on it which he used for his live stream.[72][73] Police also found four incendiary devices in his car after the attack; they were defused by the New Zealand Defence Force.[74][75] He said, on the livestream, that he had planned to set the mosque on fire.[76]

Manifesto[change | change source]

Tarrant says he is the author of a 74-page manifesto titled The Great Replacement, a reference to the "Great Replacement" and "white genocide" conspiracy theories.[7][77] It said that the attacks were planned in 2017 and the locations were selected three months before.[78] Minutes before the attacks began, the manifesto was emailed to more than 30 people, including the prime minister's office and several media outlets,[79] and links were posted on Twitter and 8chan.[80][81] Seven minutes after Tarrant sent the manifesto to parliament, it was forwarded to the parliament security team, who called the police at 1:40 p.m., around the same time the first 111 calls were made from the Al Noor Mosque.[82]

In the manifesto, several anti-immigrant ideas are said, including hate speech against migrants, white supremacist beliefs and the plan for all non-European immigrants in Europe that he claimed to be "invading his land" to be deported.[83] The manifesto displays neo-Nazi symbols such as the Black Sun and the Odin's cross. He says he isn't a Nazi,[84] instead he says he is a fascist.[85][86][87][88][89] The author said terrorists Anders Behring Breivik and Dylann Roof were an inspiration.[90][91][92] He says he agrees with British Union of Fascists leader Oswald Mosley.[93][94] The author says he first planned to attack the Al Huda Mosque in Dunedin but changed his mind after visiting Christchurch.[95][96] Tarrant also told readers to assassinate German Chancellor Angela Merkel, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and London Mayor Sadiq Khan.

Tarrant said three moments gave him his ideas. The first was the murder of an 11-year-old girl, Ebba Åkerlund, in the 2017 Stockholm attack on 7 April 2017. (Her name was part of the graffiti written on the gun he used to commit the shooting). He also said the loss of Marine Le Pen in the 2017 French presidential election was "evidence" that the chance of a democratic solution to stop non-European immigration had "vanished". The third event was his trip to France where he had a strong emotional response to his belief that the French had become a minority in their own country. He was also moved by visiting a military cemetery: "my despair turned to shame, my shame to guilt, my guilt to anger and my anger to rage".[97]

Attacks[change | change source]

At 1:32 p.m., Tarrant started his live-stream that played for 17 minutes on Facebook Live, starting with the drive to the Al Noor Mosque and ending as he drove away.[98][99] Just before the shooting, he played songs, including "Serbia Strong", a Serbian nationalist and anti-Muslim song; and "The British Grenadiers", a British military marching song.[100][101][102]

Al Noor Mosque[change | change source]

At 1:39 p.m., Tarrant parked his car in the driveway next to the Al Noor Mosque. He then armed himself with the Mossberg 930 and Windham Weaponry AR-15 rifle before walking towards the mosque.[98][103][104]

At 1:40 p.m., Tarrant approached the mosque and fired his shotgun nine times towards the front entrance, killing four worshippers. He dropped the shotgun and opened fire on people inside with the AR-15, killing two men down a hallway near the entrance and even more inside a prayer hall.[98][105][106] A worshipper, Naeem Rashid charged at Tarrant and knocked him down, dislodging a magazine from his vest in the process, but he was then shot several times and fatally wounded.[105][107][108] Rashid was posthumously awarded the Nishan-e-Shujaat and the New Zealand Cross, the highest awards of bravery in Pakistan and New Zealand, respectively.[109][110]

Tarrant fired at worshippers in the prayer hall and went outside, where he killed a man, discarded his Windham WW-15 and retrieved a Ruger AR-556 AR-15 from his car. He went to the mosque's gate and killed two people in the car park who were hiding behind cars. He went back in the mosque and shot wounded people, then went outside again, where he killed a woman near his car[111][103][98][105] before driving over her, leaving six minutes after he first got to the mosque.[105][104] He shot at worshippers who had escaped from the mosque through the windscreen and closed window of his own car using a Remington Model 870 as was driving to the Linwood Islamic Centre.[103][98][104]

At 1:46 p.m., police arrived to the mosque just as Tarrant was leaving, but his car was hidden by a bus, and at the time it was unknown what his car looked like or whether or not he had even left.[103][112] At 1:51 p.m., the livestream ended due to a bad connection, he aimed a shotgun at the driver of a vehicle and tried to fire it twice, but it failed to fire. The GoPro camera on Tarrant's helmet kept recording until he was arrested by police eight minutes later.[104][103]

Linwood Islamic Centre[change | change source]

At 1:52 p.m., Tarrant got t0 the Linwood Islamic Centre,[113] 5 kilometres (3 mi) east of the Al Noor Mosque,[114] where about 100 people were inside.[115][113] He parked his car on the driveway, preventing other cars from getting in or out.[115] According to a witness, he couldn't find the mosque's main door and shot people outside and through a window, killing four people.[115][113][116]

A worshipper named Abdul Aziz Wahabzada ran outside when Tarrant was getting another gun from his car, Aziz threw a credit card reader at him. Tarrant shot at Aziz, who picked up an empty shotgun that Tarrant dropped. He hid behind cars and tried to get Tarrant's attention by shouting. Regardless, Tarrant went into the mosque, where he shot and killed three people. When Tarrant got back to his car, Aziz came up to him again. Tarrant took a bayonet from his vest but then retreated into his car instead of attacking Aziz. Tarrant drove away at 1:55 p.m., with Aziz throwing the shotgun at his car.[117][118] Aziz was awarded the New Zealand Cross, New Zealand's highest award for bravery.[119] In May 2023, he represented recipients of the Cross at the coronation of Charles III and Camilla.[120] After being left unused, Linwood Islamic Centre was demolished in November 2023.[121][122]

Tarrant's arrest[change | change source]

A silver 2005 Subaru Outback[123] matching the description of Tarrant's car was seen by a police officer, and a chase was initiated at 1:57 p.m. Two police officers rammed his car off of the road with their police car, and Tarrant was arrested without struggle on Brougham Street in Sydenham at 1:59 p.m., 18 minutes after the first emergency call.[124][125][126] Police found the four incendiary devices in his car; they were defused by the New Zealand Defence Force.[114][127] He said, on the livestream, that he had planned to set the mosque on fire.[128]

Tarrant said that when he was being arrested, he was on his way to attack a third mosque in Ashburton, 90 km (56 mi) southwest of Christchurch.[125] He also told the police that there were "nine more shooters", and that there were "like-minded" people in Dunedin, Invercargill, and Ashburton, but when he was interviewed later, he told the truth and said that he had did it alone.[129]

Victims[change | change source]

| Citizenship | Deaths |

|---|---|

| 27[b] | |

| 8 | |

| 5 | |

| 3 | |

| 2 | |

| 1 | |

| 1 | |

| 1 | |

| 1 | |

| 1 | |

| 1[131] | |

| Total | 51 |

Fifty-one people died from the attacks: 44 at the Al Noor Mosque and seven at the Linwood Islamic Centre. All but four were male.[130] Their ages ranged from three to 77 years old.[132] Thirty-five others were injured at the Al Noor Mosque and five at Linwood.[133]

Aftermath[change | change source]

Legal[change | change source]

Arraignment[change | change source]

Tarrant appeared in the Christchurch District Court on 16 March, where he was charged with one count of murder.[134] The judge ordered that the courtroom would be closed to the public except for news reporters and allowed Tarrant to be filmed and photographed as long as his face would censored when shown in media coverage.[135] In court, Tarrant smiled at reporters and made an inverted OK gesture below his waist, said to be a "white power" sign.[136]

The case was transferred to the High Court, and Tarrant was kept in custody as his lawyer did not seek bail.[137] He was transferred to the country's only maximum-security unit at Auckland Prison.[138] He made a formal complaint about his conditions in the prison had no access to newspapers, television, Internet, visitors, or phone calls.[139][needs update] On 4 April, police said they had increased the number of charges to 89, 50 for murder and 39 for attempted murder, with other charges still being decided.[140] At the next hearing on 5 April, Tarrant was ordered by the judge to have a psychiatric assessment of his mental fitness to see if he could stand trial.[141]

On 20 May, a new charge of committing in a terrorist act was given to Tarrant under the Terrorism Suppression Act 2002. One murder charge and one attempted murder charge were added, bringing the total to 51 and 40.[142]

Pre-trial detention[change | change source]

On 14 June 2019, Tarrant appeared at the Christchurch High Court via audio-visual link from Auckland Prison. Through his lawyer, he pleaded not guilty to one count of engaging in a terrorist act, 51 counts of murder, and 40 counts of attempted murder. Mental health assessments showed no issues regarding his fitness to plead or stand trial. The trial was first set to start on 4 May 2020,[143] but it was pushed back to 2 June 2020 to avoid happening at the same time as the Islamic holy month of Ramadan.[144]

During his time in prison, Tarrant was able to send seven letters, one of which was subsequently posted on the Internet message boards 4chan and 8chan by the person who was sent the letters. Minister of Corrections Kelvin Davis and the Department of Corrections were criticised for letting the sending of the letters happen.[145] Prime Minister Ardern said that the Government would look into amending the Corrections Act 2004 to restrict what mail can be given to and sent by prisoners.[146][147]

Guilty plea and sentencing arrangements[change | change source]

On 26 March 2020, Tarrant appeared at the Christchurch High Court via audio-visual link from Auckland Prison. He pleaded guilty to all 92 charges. As it was happening during the nationwide COVID-19 pandemic lockdown, the public was barred from the hearing. Reporters and representatives for the Al-Noor and Linwood mosques were in the courtroom.[148] According to media reports, Tarrant's lawyers had informed the courts that their client was thinking about changing his plea. On 25 March, Tarrant gave his lawyers formal written instructions confirming that he wanted to change his pleas to guilty. In response, court authorities began making plans for the case to be called as soon as possible in the middle of the COVID-19 lockdown.[149][150] The judge convicted Tarrant on all charges and kept him in custody to await sentencing.[source?]

On 10 July, the government said that overseas victims of the shootings would get border exemptions and financial help to fly to New Zealand for the sentencing.[151] On 13 July, it was reported that Tarrant had dismissed his lawyers and would be representing himself during sentencing proceedings.[152][153]

Sentencing[change | change source]

Sentencing began on 24 August 2020 before Justice Cameron Mander at the Christchurch High Court,[154] and it was televised.[155] Tarrant did not oppose the sentence put forward and declined to address the court.[156][157] The Crown prosecutors showed the court how Tarrant had meticulously planned the two shootings and more attacks,[158][159] while survivors and their relatives gave victim impact statements, which were shown by national and international media.[160] Tarrant was then sentenced to life imprisonment without the possibility of parole for each of the 51 murders,[161] and life imprisonment for committing in a terrorist act and 40 attempted murders.[162] The sentence is New Zealand's first terrorism conviction.[163][164] It was also the first time that life imprisonment without parole, the maximum sentence available in New Zealand, had been given.[note 1]

After the sentencing, Deputy Prime Minister Winston Peters called for Tarrant to serve his sentence in Australia to stop New Zealand having to pay the costs for his life imprisonment. The cost of housing Tarrant in prison was estimated at NZ$4,930 per day,[166]

Imprisonment[change | change source]

On 14 April 2021, Tarrant appealed against his prison conditions and being classed as a "terrorist entity" at the Auckland High Court. According to media reports, he is being imprisoned at a special "prison within a prison" known as a "Prisoners of Extreme Risk Unit" with two other prisoners. Eighteen guards have been tasked guard Tarrant, who is living in his own area.[167][168] On 24 April, Tarrant abandoned the appeal.[169]

In November 2021, Tarrant's new lawyer said that Tarrant wanted to appeal against his sentence and conviction, claiming that his conditions went against the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990. Survivors have criticised Tarrant's appeal as an attempt to "re-traumatise" the Muslim community.[170][171]

Governmental response[change | change source]

Police told mosques to close until considered safe to reopen and sent officers to patrol and protect places in Christchurch.[172] All Air New Zealand Link flights departing from Christchurch Airport were cancelled due to the absence of security at the terminal.[173][174] Security was increased at Parliament, and public tours of the buildings were cancelled.[175] In Dunedin, the Police Armed Offenders Squad searched a house, reported to have been rented by Tarrant,[176][177] and shut off part of the street in Andersons Bay because Tarrant had said on social media that he had originally planned to target the Al Huda Mosque in that city.[178][179]

For the first time in New Zealand history, the terrorism threat level was raised to high.[180] Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern called the attacks an "act of extreme violence" on "one of New Zealand's darkest days".[181] She said it was a "well-planned" attack[182] and said that the person who committed the attacks to be "nameless" while telling the public to say the victims' names instead.[183] Ardern directed that flags on public buildings be flown at half-mast.[184]

In May 2019, the NZ Transport Agency offered to replace any vehicle number plates with the prefix "GUN" on request.[185]

In mid-October 2019, Ardern gave bravery awards to the two police officers who arrested Tarrant at the annual Police Association Conference in Wellington.[186] On 1 September 2020, Prime Minister Ardern designated Tarrant as a terrorist entity, freezing his assets and making it a criminal offence for anyone to support him with money.[187]

Media response[change | change source]

For the three months after the shooting, almost 1,000 reports were published in news outlets in New Zealand. Less than 10% of news reports published by major media outlets mentioned Tarrant's name. Susanna Every-Palmer, a psychiatrist, said that the media chose to not Tarrant fame and not show his views. The court made the media to censor Tarrant's face when showing the legal proceedings so in New Zealand, he stayed faceless and nameless. Instead, media coverage focused on the victims and their families.[188][189]

The media response in Australia was different, focusing on the violence of the attack, as well as Tarrant and his manifesto. For example, The Australian published audio of cries for help, and The Herald Sun wrote dramatic descriptions of victims being shot and used poetry. Coverage of the victims was focused on things like bloodshed, injuries, and graves being dug.[189]

Other responses in New Zealand[change | change source]

The third test cricket between New Zealand and Bangladesh, that was supposed to happen at Hagley Oval in Hagley Park on 16 March, was cancelled because of security reasons.[190] The Bangladesh team were planning to go to the Friday prayer at the Al Noor Mosque and were moments from entering the building when the incident began.[191][192] The players then fled on foot to Hagley Oval.[193] Two days later, Canterbury cancelled their match against Wellington in the cricket tournament.[194] The rugby match between the Crusaders, based in Christchurch, and Highlanders, based in Dunedin, was cancelled as "a mark of respect for the events".[195]

Canadian rock singer-songwriter Bryan Adams and American thrash metal band Slayer cancelled their concerts that were supposed to happen in Christchurch on 17 March, two days after the shootings.[196]

Mosques around the World held vigils and tributes.[197] The mayor of Christchurch, Lianne Dalziel, encouraged people to put flowers outside the city's gardens.[198] School pupils and other groups performed haka to honour the people killed in the attacks.[199][200] Street gangs including the Mongrel Mob, Black Power, and the King Cobras sent members to mosques around the country to help protect them during prayer time.[201]

One week after the attacks, an open-air Friday prayer service was held in Hagley Park. Broadcast across New Zealand on radio and television, it was attended by 20,000 people along with Jacinda Ardern,[202] who said, "New Zealand mourns with you. We are one." The imam of the Al Noor Mosque thanked New Zealanders for their support and said, "We are broken-hearted but we are not broken."[203]

Operation Whakahaumanu[change | change source]

After the attack, New Zealand Police started Operation Whakahaumanu. The operation was made to reassure New Zealanders after the attack by putting police around streets, schools and religious buildings and to also investigate people who have similar ideas to the gunman.

Charity[change | change source]

An online charity started to support victims and their families had, as of August 2020,[ref] raised over 10 million New Zealand dollars.[204][205] Counting other fundraisers, a combined total of $8.4 million had been raised for the victims and their families[206]

In late June, it was reported that the Jewish Federation of Greater Pittsburgh had raised more than NZ$967,500 (US$650,000) through its fund for the victims of the Christchurch mosque shootings. This amount also had $60,000 raised by Tree of Life – Or L'Simcha Congregationfollowing the Pittsburgh synagogue shooting in late October 2018.[207]

Related arrests and incidents[change | change source]

New Zealand[change | change source]

Police arrested four people on 15 March,[208][209][210] including a woman and a man, after finding a gun in a vehicle which they were travelling in together.[211] A 30-year-old man said he was arrested when he arrived at Papanui High School to pick up his 13-year-old brother-in-law. He was in camouflage clothing.[212][213]

On 4 March 2020, a 19-year-old Christchurch man was arrested for allegedly making a terror threat against the Al Noor Mosque on Telegram.[214] Media reports said the man was Sam Brittenden, a member of the white supremacist group Action Zealandia.[215][216] On 4 March 2021, a 27-year-old man was charged with "threatening to kill" after making an online threat against both the Linwood Islamic Centre and the Al Noor Mosque on 4chan.[217]

Outside New Zealand[change | change source]

On 18 March 2019, the Australian police raided the homes of Tarrant's sister and mother near Coffs Harbour and Maclean in New South Wales. Tarrant's sister and mother were helping the police investigation.[218][219]

On 19 March 2019, an Australian man who had praised the shootings on social media was indicted on one count of possession of a gun without a licence and four counts of using an illegal weapon. He was released on bail on the condition that he stay offline.[220][needs update]

A 24-year-old man from Oldham, Greater Manchester, United Kingdom, was arrested on 16 March for making posts on Facebook supporting the shootings.[221][222][needs update]

On 20 March, an employee of a company based in the United Arab Emirates, was fired by his company and deported for supporting the shootings.[223]

Thomas Bolin, a 22-year-old living in New York, made Facebook messages praising the shootings and talking about a plan to do a similar attack in the United States with his cousin. Bolin was convicted of lying to the FBI for saying he did not own any guns.[224]

Inspired incidents[change | change source]

Nine days after the attack, a mosque in Escondido, California, was set on fire. Police found graffiti on the mosque's driveway that said "For Brenton Tarrant", the police investigated the fire as a terrorist attack.[225][226] A mass shooting later took place at a synagogue in Poway, California on 27 April 2019, killing a person and injuring three others. The perpetrator of the shooting, 19-year-old John Earnest, also said he committed the fire and praised the Christchurch shootings and Tarrant in a manifesto.[227][228] On September 30, 2021, Earnest was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole.[229]

On 3 August 2019, 21-year-old Patrick Crusius opened fire and killed 23 people and injured 22 others in a mass shooting at a Walmart in El Paso, Texas, targeting Mexicans. In a manifesto posted to 8chan /pol/ board, he said he supported Tarrant and was inspired by him.[230][231][232]

On 10 August 2019, 21-year-old Philip Manshaus murdered his Chinese adopted stepsister at their home before travelling to a mosque in Bærum, Norway and trying to commit a mass shooting, before being disarmed by a worshipper, Mohammad Rafiq. He called Tarrant as a "saint" online.[233] Manshaus was sentenced to 21 years for the attack.[234]

On 27 January 2021, the Singaporean intelligence agency said it had arrested a 16-year-old Protestant Indian for plotting to attack the Yusof Ishak Mosque and Assyafaah Mosque on the anniversary of the Christchurch shootings. The youth wrote a manifesto that called Tarrant as a "saint" and praised the shootings as the "justifiable killing of Muslims". The boy bought a machete and protective vest which he planned to use for the attack.[235][236] In January 2024, the youth was released after spending almost three years in detention.

On 14 May 2022, 18-year-old Payton Gendron killed ten people and injured three others at a Tops Friendly Markets store in Buffalo, New York, targeting Black people. He livestreamed the shooting on Twitch and published a manifesto where he wrote that he was inspired by Tarrant. In response, there a ban on the sharing of Gendron's manifesto within New Zealand.[237]

Response[change | change source]

World leaders[change | change source]

Queen Elizabeth II, New Zealand's head of state, said she was "deeply saddened" by the shootings.[238] Other world leaders also condemned the attacks.[239][note 2]

The prime minister of Pakistan, Imran Khan, said that Naeem Rashid, the Pakistani worshipper who charged at Tarrant and died, would be honoured with a national award.[240]

President Donald Trump called the shootings a "horrible massacre".[241]

Far-right[change | change source]

Two New Zealand-based anti-immigration groups, the Dominion Movement and the New Zealand National Front, condemned the attacks and shut their websites down.[242] Others in the far-right celebrated the attacks.[243] Tarrant's manifesto, The Great Replacement, was translated and shared in more than a dozen different languages[243] The United Kingdom's domestic intelligence service, MI5, launched an inquiry into Tarrant's possible links to the British far-right.[244]

Islamic groups[change | change source]

Ahmed Bhamji, chair of the largest mosque in New Zealand,[245] spoke at a rally on 23 March in front of one thousand people.[246][247] He claimed that Mossad, the Israeli intelligence agency, committed and planned the attack. The claim has been called an antisemitic conspiracy theory. The chairman of the Federation of Islamic Associations of New Zealand said not all New Zealand Muslims agreeed with Bhamji's claim.[245][246][248]

People and countries mentioned by Tarrant[change | change source]

Just before committing the attacks, Tarrant told the audience of the livestream to subscribe to PewDiePie, a YouTuber, because at the time, PewDiePie was attempting to get more subscribers than the Indian music record T-Series.[249] PewDiePie, real name Felix Kjellberg, posted on Twitter that he "felt absolutely sickened" to have his name spoken by Tarrant.[250]

During the attacks, Tarrant played the song "Fire" by The Crazy World of Arthur Brown.[251] In a Facebook post, singer Arthur Brown posted his "horror and sadness" at the use of his song during the shootings, and cancelled an appearance at Waterloo Records shortly after the shootings.[252] Tarrant also played the Serbian nationalist song "Serbia Strong", he main singer of the song, Željko Grmuša, said, "It is terrible what that guy did in New Zealand, I feel sorry for all those innocent people."[253]

References[change | change source]

- ↑ Roy, Eleanor Ainge; Sherwood, Harriet; Parveen, Nazia (15 March 2019). "Christchurch attack: suspect had white-supremacist symbols on weapons". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 15 March 2019. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

A bomb disposal team was called in to dismantle explosive devices found in a stopped car.

- ↑ "'There Will Be Changes' to Gun Laws, New Zealand Prime Minister Says". The New York Times. 17 March 2019. Archived from the original on 17 March 2019. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- ↑ "Mosque attack sentencing: Gunman's plan of terror outlined in court". The New Zealand Herald. 13 February 2024. Archived from the original on 15 January 2024. Retrieved 13 February 2024.

- ↑ Welby, Peter (16 March 2019). "Ranting 'manifesto' exposes the mixed-up mind of a terrorist". Arab News. Archived from the original on 17 March 2019. Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- ↑ Achenbach, Joel (18 August 2019). "Two mass killings a world apart share a common theme: 'ecofascism'". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 22 June 2020.

- ↑ Campbell, Charlie (21 March 2019). "The New Zealand Attacks Show How White Supremacy Went From a Homegrown Issue to a Global Threat". Time. Archived from the original on 3 November 2023. Retrieved 3 November 2023.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Gilsinan, Kathy (15 March 2019). "How White-Supremacist Violence Echoes Other Forms of Terrorism". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 17 March 2019. Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Cite error: The named reference

:12was used but no text was provided for refs named (see the help page). - ↑ Ensor, Blair; Sherwood, Sam. "Christchurch mosque attacks: Accused pleads guilty to murder, attempted murder and terrorism". Stuff. Archived from the original on 8 July 2020. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ↑ Bayer, Kurt (3 July 2020). "Christchurch mosque shooting: Gunman's sentencing confirmed to start on August 24". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 3 July 2020. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- ↑ Quinlivan, Mark; McCarron, Heather. "Christchurch shooting: Alleged gunman Brenton Tarrant's trial delayed". Newshub. Archived from the original on 13 June 2020. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- ↑ Cite error: The named reference

third_appearancewas used but no text was provided for refs named (see the help page). - ↑ Lourens, Mariné (27 August 2020). "Christchurch mosque gunman jailed 'until his last gasp'". Stuff. Archived from the original on 27 August 2020. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- ↑ "New Zealand mosque shooter given life in prison for 'wicked' crimes". Reuters. 27 August 2020. Archived from the original on 27 August 2020. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- ↑ "'A loner with a lot of money': A look into mosque gunman's past". NZ Herald. 2024-05-29. Retrieved 2024-05-28.

- ↑ Chung, Sarah Keoghan, Laura (2019-03-15). "From local gym trainer to mosque shooting: Alleged Christchurch shooter's upbringing in Grafton". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2024-05-28.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ 17.0 17.1 "The individual's upbringing in Australia". Royal Commission of Inquiry into the Attack on Christchurch Mosques on 15 March 2019. Retrieved 2024-05-28.

- ↑ "The individual's upbringing in Australia". Royal Commission of Inquiry into the Attack on Christchurch Mosques on 15 March 2019. Retrieved 2024-05-28.

- ↑ "Report of the Royal Commission of Inquiry into the terrorist attack on Christchurch masjidain on 15 March 2019" (PDF). Royal Commission. pp. 168–170. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 July 2023. Retrieved 11 December 2023.

- ↑ Beynen, Martin van; Sherwood, Sam (8 December 2020). "New Zealand 'ideal' for mosque shooter to plan his terrorist attack, royal commission finds". Stuff. Archived from the original on 8 December 2020. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- ↑ "Who is Christchurch mosque shooting accused? Brenton Tarrant member of Bruce Rifle Club in Milton". The New Zealand Herald. 15 March 2019. Archived from the original on 16 March 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- ↑ "Perpetrator of New Zealand terrorist attack visited Turkey 'twice'". TRT World. 15 March 2019. Archived from the original on 17 March 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- ↑ "Brenton Tarrant: Suspected New Zealand attacker 'met extreme right-wing groups' during Europe visit, according to security sources". The Independent. 15 March 2019. Archived from the original on 15 March 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

The man arrested over the murder of 49 people at mosques in New Zealand is believed to have met extreme right-wing groups during a visit to Europe two years ago, according to security sources.

- ↑ Multiple sources:

- "Suspected New Zealand attacker donated to Austrian far-right group, officials say". Reuters/NBC News. 5 April 2019. Archived from the original on 8 March 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- "Christchurch mosque shootings: Accused gunman donated $3650 to far-right French group Generation Identity". The New Zealand Herald. 5 April 2019. Archived from the original on 30 July 2020. Retrieved 5 April 2019.

- Wilson, Jason (15 May 2019). "Christchurch shooter's links to Austrian far right 'more extensive than thought'". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- ↑ Saunders, Doug (15 March 2022). "Opinion: The Christchurch massacre may have had a Canadian connection – but there's a reason you may not know about it". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on 15 March 2022. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- ↑ Mann, Alex; Nguyen, Kevin; Gregory, Katharine (23 March 2019). "Christchurch shooting accused Brenton Tarrant supports Australian far-right figure Blair Cottrell". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 23 March 2019. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- ↑ Nguyen, Kevin (10 April 2019). "'This marks you': Christchurch shooter sent death threat two years ago". ABC News. Archived from the original on 12 April 2019. Retrieved 12 April 2019.

- ↑ Cite error: The named reference

AP.Eluded2was used but no text was provided for refs named (see the help page). - ↑ "Christchurch shooter was Bulgarian guesthouse's first-ever Australian guest". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 31 March 2019. Archived from the original on 14 June 2022. Retrieved 14 June 2022.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Gec, Jovana (16 March 2019). "New Zealand gunman entranced with Ottoman sites in Europe". Associated Press News. Archived from the original on 16 March 2019. Retrieved 20 March 2019.

- ↑ Schindler, John R. (20 March 2019). "Ghosts of the Balkan wars are returning in unlikely places". The Spectator. Archived from the original on 22 March 2019. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Cite error: The named reference

Coalson2was used but no text was provided for refs named (see the help page). - ↑ 33.0 33.1 Cite error: The named reference

Zivanovic2was used but no text was provided for refs named (see the help page). - ↑ Cite error: The named reference

AP.Eluded3was used but no text was provided for refs named (see the help page). - ↑ Report of the Royal Commission of Inquiry into the terrorist attack on Christchurch masjidain on 15 March 2019 (PDF). p. 24. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 July 2023. Retrieved 3 November 2023.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Cite error: The named reference

AP.Eludedwas used but no text was provided for refs named (see the help page). - ↑ Dunedin, Candace Sutton in (17 March 2019). "Christchurch massacre: Brenton Tarrant's life in Dunedin, NZ". News.com.au. Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 2 April 2019.

- ↑ "Christchurch shooting accused Brenton Tarrant described as a 'recluse' by neighbours". Stuff. 17 March 2019. Archived from the original on 30 March 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- ↑ Reid, Melanie; Jennings, Mark (25 March 2019). "Shooter trained at Otago gun club". Newsroom. Archived from the original on 4 November 2021. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

- ↑ "Christchurch mosque shootings: Bruce Rifle Club closes in wake of terror". The New Zealand Herald. 17 March 2019. ISSN 1170-0777. Archived from the original on 18 March 2019. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- ↑ O'Callaghan, Jody (7 December 2020). "March 15 terrorist accidentally shot himself months before mosque attack". Stuff. Archived from the original on 7 December 2020. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- ↑ "General life in New Zealand". Royal Commission of Inquiry into the Attack on Christchurch Mosques on 15 March 2019. Retrieved 2024-05-11.

- ↑ Massola, James (2020-12-08). "'I don't have enemies': How Christchurch terrorist slipped through the net". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2024-05-11.

- ↑ "Brenton Tarrant: The 'ordinary white man' turned mass murderer". The Daily Telegraph. 16 March 2019. Archived from the original on 15 March 2019. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ↑ "Christchurch shooting: Survivors convinced gunman visited mosque to learn layout". Newshub. Archived from the original on 15 April 2020. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ↑ "Questions asked by the community". Royal Commission of Inquiry into the Attack on Christchurch Mosques on 15 March 2019. Archived from the original on 5 August 2021. Retrieved 5 August 2021.

- ↑ "Christchurch mosque shootings: Police rule out that gunman entered mosque prior to attack". The New Zealand Herald. 12 April 2020. ISSN 1170-0777. Archived from the original on 27 April 2020. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Cite error: The named reference

TheAttackRoyalCommissionwas used but no text was provided for refs named (see the help page). - ↑ Bayer, Kurt; Leasl, Anna (24 August 2020). "Christchurch mosque terror attack sentencing: Gunman Brenton Tarrant planned to attack three mosques". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 4 September 2020. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ↑ Report of the Royal Commission of Inquiry into the terrorist attack on Christchurch masjidain on 15 March 2019 (PDF). pp. 49–51. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 July 2023. Retrieved 3 November 2023.

- ↑ "Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern's focus on strengthening current gun laws after Christchurch terror attacks". Radio New Zealand. 18 March 2019. Archived from the original on 21 March 2019. Retrieved 20 March 2019.

- ↑ Cite error: The named reference

rnz002was used but no text was provided for refs named (see the help page). - ↑ Pannett, Rachel; Taylor, Rob; Hoyle, Rhiannon (18 March 2019). "New Zealand Shootings: Brenton Tarrant Bought Four Guns Legally Online". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 19 March 2019. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- ↑ "New Zealand cabinet backs change to gun laws within 10 days after mosque shooting". The Independent. 18 March 2019. Archived from the original on 29 March 2019. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- ↑ "Table 6: The individual's online purchases of magazines 2017–2018". Royal Commission of Inquiry into the Attack on Christchurch Mosques on 15 March 2019. 17 August 2017. Archived from the original on 30 October 2023. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- ↑ "Christchurch mosque shootings: Briefing to Police Minister Stuart Nash shows gun law loophole also exploited by Northland siege killer Quinn Paterson". The New Zealand Herald. 20 March 2019. Archived from the original on 2 May 2019. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- ↑ Perry, Nick; Williams, Juliet (21 March 2019). "Thousands descend on site of New Zealand mosque attacks to observe emotional Muslim prayer". The Globe and Mail. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 22 March 2019. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- ↑ "Christchurch shootings: NZ cabinet backs tighter gun laws". BBC News. 18 March 2019. Archived from the original on 20 March 2019. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- ↑ Report of the Royal Commission of Inquiry into the terrorist attack on Christchurch masjidain on 15 March 2019 (PDF). p. 70. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 July 2023. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 Cite error: The named reference

Coalsonwas used but no text was provided for refs named (see the help page). - ↑ Cite error: The named reference

Zivanovicwas used but no text was provided for refs named (see the help page). - ↑ 62.0 62.1 "Mosque shooter brandished material glorifying Serb nationalism". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 15 March 2019. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 "New Zealand mosque shooter names his 'idols' on weapons he used in massacre". Daily Sabah. Istanbul. 15 March 2019. Archived from the original on 15 March 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- ↑ "New Zealand terror suspect wrote Italian shooter's name on his gun". The Local Italy. 15 March 2019. Archived from the original on 18 March 2019. Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- ↑ Badshah, Nadeem (15 March 2019). "Finsbury Park mosque worshippers shocked by New Zealand terror attack". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 15 March 2019. Retrieved 18 June 2022.

- ↑ Dedon, Theodore G. (2021), Mannion, Gerard; Doyle, Dennis M.; Dedon, Theodore G. (eds.), "From Julius Evola to Anders Breivik: The Invented Tradition of Far-Right Christianity", Ecumenical Perspectives Five Hundred Years After Luther's Reformation, Pathways for Ecumenical and Interreligious Dialogue, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 83–105, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-68360-3_6, ISBN 978-3-030-68360-3, S2CID 235865852, archived from the original on 6 November 2023, retrieved 30 April 2023

- ↑ Hartleb, Florian (2020), "Offenders and Terrorism. Ideology, Motives, Objectives", Lone Wolves, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 63–122, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-36153-2_3, ISBN 978-3-030-36153-2, S2CID 212843876, archived from the original on 6 November 2023, retrieved 30 April 2023

- ↑ "St. Michael's Cross". Anti-Defamation League. Archived from the original on 14 May 2022. Retrieved 14 June 2022.

- ↑ "Like, Share, Recruit: How a White-Supremacist Militia Uses Facebook to Radicalize and Train New Members". 7 January 2021. Archived from the original on 28 February 2022. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

The Christchurch mosque attacker, who livestreamed the atrocity on Facebook, had been radicalized by far-right material largely on YouTube and Facebook, according to a New Zealand government report released in December 2020. He had spent time in Ukraine in 2015 and mentioned plans to move to the country permanently. "We know that when he was in that part of the world, he was making contact with far-right groups," says Andrew Little, the Minister responsible for the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service. Little says he does not know if these groups included Azov. But during the attack, the shooter wore a flak jacket bearing a black sun, the symbol commonly used by the Azov Battalion.

- ↑ Macklin, Graham (2019). "The Christchurch Attacks: Livestream Terror in the Viral Video Age" (PDF). CTC Sentinel. 12 (6): 23. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 May 2023. Retrieved 30 April 2023.

- ↑ Report of the Royal Commission of Inquiry into the terrorist attack on Christchurch masjidain on 15 March 2019 (PDF). Royal Commission of Inquiry into the Attack on Christchurch Mosques on 15 March 2019. p. 46. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 July 2023. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- ↑ Cite error: The named reference

rnz003was used but no text was provided for refs named (see the help page). - ↑ "Other equipment for the purposes of the terrorist attack". Royal Commission of Inquiry into the Attack on Christchurch Mosques on 15 March 2019. 17 August 2017. Archived from the original on 30 October 2023. Retrieved 25 October 2023.

- ↑ Report of the Royal Commission of Inquiry into the terrorist attack on Christchurch masjidain on 15 March 2019 (PDF). p. 45. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 July 2023. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- ↑ "Christchurch mosque shooting kills 49, gun laws will change PM says". Stuff (company). 16 March 2019. Archived from the original on 15 March 2019. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ↑ Hendrix, Steve (16 March 2019). "'Let's get this party started': New Zealand shooting suspect narrated his chilling rampage". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 21 March 2019. Retrieved 20 March 2019.

- ↑ Darby, Luke (5 August 2019). "How the 'Great Replacement' conspiracy theory has inspired white supremacist killers". The Telegraph. London – via ProQuest.

- ↑ "Terrorism security expert Chris Kumeroa says New Zealanders need to be alert to potential threats". Stuff (company). Archived from the original on 21 March 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- ↑ "Jacinda Ardern's office received manifesto from Christchurch shooter minutes before attack". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 17 March 2019. Archived from the original on 17 March 2019. Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- ↑ Wong, Charlene (15 March 2019). "The Manifesto of Brenton Tarrant – a right-wing terrorist on a Crusade". Archived from the original on 15 March 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- ↑ "Australian man named as NZ mosque gunman". The West Australian. 15 March 2019. Archived from the original on 19 April 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- ↑ "Operation Deans / Evidential Overview" (PDF). New Zealand Police. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 July 2023. Retrieved 21 August 2023.

- ↑ Gelineau, Kristen; Gambrell, Jon. "New Zealand mosque shooter is a white nationalist who hates immigrants, documents and video reveal". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 2 June 2020. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- ↑ Dearden, Lizzie (16 March 2019). "New Zealand attack: How nonsensical white genocide conspiracy theory cited by gunman is spreading poison around the world". Independent. Archived from the original on 16 March 2019. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ↑ Zivanovic, Maja (15 March 2019). "New Zealand Mosque Gunman 'Inspired by Balkan Nationalists'". Balkaninsight.com. Balkaninsight. Archived from the original on 22 September 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- ↑ "Invaders from India, Enemies in East: New Zealand Shooter's Post After a Q&A Session With Himself". News18. 16 March 2019. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ↑ "Attacker posted 87-page "anti-immigrant, anti-Muslim" manifesto". CNN. 15 March 2019. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- ↑ Multiple sources:

- Achenbach, Joel (18 August 2019). "Two mass killings a world apart share a common theme: 'ecofascism'". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 22 June 2020. Retrieved 19 September 2019.

- "New Zealand suspect Brenton Tarrant 'says he is racist eco-fascist who is mostly introverted'". ITV News. 15 March 2019. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- Weissmann, Jordan (15 March 2019). "What the Christchurch Attacker's Manifesto Tells Us". Slate. Archived from the original on 22 May 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- Bolt, Andrew (15 March 2019). "Mosque Shooting in New Zealand. Many Dead". Herald Sun. Archived from the original on 17 December 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- ↑ Purtill, James (15 March 2019). "Fuelled by a toxic, alt-right echo chamber, Christchurch shooter's views were celebrated online". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 15 March 2019. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ↑ Ravndal, Jacob Aasland (16 March 2019). "The Dark Web Enabled the Christchurch Killer". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 18 March 2019. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- ↑ Taylor, Adam (16 March 2019). "Christchurch suspect claimed 'brief contact' with Norwegian mass murderer". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 15 March 2019. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- ↑ "New Zealand mosque shooter mentioned Dylann Roof in manifesto". Associated Press and The Post and Courier. 15 March 2019. Archived from the original on 18 June 2022. Retrieved 18 June 2022.

- ↑ Kampeas, Ron (15 March 2019). "New Zealand killer says his role model was Nazi-allied British fascist". The Times of Israel. Archived from the original on 18 June 2022. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- ↑ "New Zealand Shooting Suspect Praised China For 'Lacking Diversity'". Radio Free Asia. 18 March 2019. Archived from the original on 4 July 2022. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- ↑ Kidd, Rob; Miller, Tim (16 March 2019). "Police confirm Dunedin property linked to terror attack". Otago Daily Times. Archived from the original on 15 March 2019. Retrieved 2 August 2019.

- ↑ Sherwood, Sam (21 March 2019). "Ashburton Muslims in gunman's sights 'feeling lucky' Christchurch shooter stopped". Stuff (company). Archived from the original on 9 May 2019. Retrieved 2 August 2019.

- ↑ Dafinger, Johannes; Florin, Moritz (2022). A Transnational History of Right Wing Terrorism: Political Violence and the Far Right in Eastern and Western Europe since 1900. United Kingdom: Routledge. p. 219.

- ↑ 98.0 98.1 98.2 98.3 98.4 Cite error: The named reference

rnz004was used but no text was provided for refs named (see the help page). - ↑ "Christchurch mosque shootings: Gunman livestreamed 17 minutes of shooting terror". The New Zealand Herald. 15 March 2019. Archived from the original on 15 March 2019. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ↑ Koziol, Michael (15 March 2019). "Christchurch shooter's manifesto reveals an obsession with white supremacy over Muslims". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 15 March 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- ↑ Coalson, Robert. "Christchurch Attacks: Suspect Took Inspiration From Former Yugoslavia's Ethnically Fueled Wars". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- ↑ Doyle, Gerry. "New Zealand mosque gunman's plan began and ended online". Reuters. Archived from the original on 15 March 2019. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ↑ 103.0 103.1 103.2 103.3 103.4 Cite error: The named reference

Operation Deans2was used but no text was provided for refs named (see the help page). - ↑ 104.0 104.1 104.2 104.3 "The terrorist attack". Royal Commission of Inquiry into the Attack on Christchurch Mosques on 15 March 2019. Archived from the original on 23 December 2020. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- ↑ 105.0 105.1 105.2 105.3 "The Queen v. Brenton Harrison Tarrant: Sentencing Remarks of Mander J" (PDF). High Court of New Zealand. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 October 2023. Retrieved 21 October 2023.

- ↑ Multiple sources:

- "'Hello brother': Muslim worshipper's 'last words' to gunman". Al Jazeera. 15 March 2019. Archived from the original on 15 March 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- "'Hello brother', first Christchurch mosque victim said to shooter". Toronto City News. 15 March 2019. Archived from the original on 29 May 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- Horton, Alex (15 March 2019). "With strobe lights and guns bearing neo-Nazi slogans, New Zealand gunman plotted a massacre". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 7 April 2019. Retrieved 19 April 2019.

- ↑ "Christchurch shootings: Stories of heroism emerge from attacks". BBC. Archived from the original on 17 March 2019. Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- ↑ Mackenzie, James; Russell, Ros. "Pakistan salutes hero of New Zealand mosque shooting". Reuters. Archived from the original on 19 March 2019. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- ↑ Cite error: The named reference

dpmc-honourswas used but no text was provided for refs named (see the help page). - ↑ "Mosque attack hero given bravery award in Pakistan". Radio New Zealand. 6 May 2019. Archived from the original on 15 December 2021. Retrieved 16 December 2021.

- ↑ "5.3 Firearms, ammunition and other equipment used in the terrorist attack". Royal Commission of Inquiry into the Attack on Christchurch Mosques on 15 March 2019. 17 August 2017. Archived from the original on 30 October 2023. Retrieved 25 October 2023.

- ↑ "Christchurch terror attack: Police release official timeline". Newshub. Archived from the original on 28 February 2020. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- ↑ 113.0 113.1 113.2 Cite error: The named reference

TheAttackRoyalCommission3was used but no text was provided for refs named (see the help page). - ↑ 114.0 114.1 Perry, Nick; Baker, Mark (15 March 2019). "Mosque shootings kill 49; white racist claims responsibility". Star Tribune. Archived from the original on 21 March 2019.

- ↑ 115.0 115.1 115.2 Cite error: The named reference

rnz005was used but no text was provided for refs named (see the help page). - ↑ Macdonald, Nikki (18 March 2019). "Alleged shooter approached Linwood mosque from wrong side, giving those inside time to hide, survivor says". Stuff (company). Archived from the original on 18 March 2019. Retrieved 20 March 2019.

- ↑ Cite error: The named reference

SentencingRemarks2was used but no text was provided for refs named (see the help page). - ↑ Multiple sources:

- Perry, Nick. "Man who stood up to mosque gunman probably saved lives". Associated Press News. Archived from the original on 17 March 2019. Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- Saber, Nasim; Ahmadi, Naser. "New Zealand terror attacks: The hero of Christchurch talks". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- "Dodging bullets, a father of 4 confronted the New Zealand shooter and saved lives". CNN. Archived from the original on 20 March 2019. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- ↑ "Special Honours List 16 December 2021 – Citations for New Zealand Bravery Awards". Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet. 16 December 2021. Archived from the original on 15 December 2021. Retrieved 16 December 2021.

- ↑ "Coronation order of service in full". BBC News. 5 May 2023. Archived from the original on 6 May 2023. Retrieved 6 May 2023.

- ↑ O'Callaghan, Jody (20 November 2023). "Tears and prayers as Linwood mosque gets demolished". Stuff. Archived from the original on 11 December 2023. Retrieved 11 December 2023.

- ↑ "Christchurch's Linwood Mosque demolished after 2019 attacks". 1 News. 20 November 2023. Archived from the original on 11 December 2023. Retrieved 11 December 2023.

- ↑ "Christchurch terror attack: The gunman's next target". Newshub. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ↑ Cite error: The named reference

SentencingRemarks3was used but no text was provided for refs named (see the help page). - ↑ 125.0 125.1 Cite error: The named reference

TheAttackRoyalCommission4was used but no text was provided for refs named (see the help page). - ↑ "Mosque attacks timeline: 18 minutes from first call to arrest". RNZ. 17 April 2019. Archived from the original on 15 February 2020. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

- ↑ Cite error: The named reference

:52was used but no text was provided for refs named (see the help page). - ↑ Cite error: The named reference

:62was used but no text was provided for refs named (see the help page). - ↑ Report of the Royal Commission of Inquiry into the terrorist attack on Christchurch masjidain on 15 March 2019 (PDF). pp. 72–73. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 July 2023. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- ↑ 130.0 130.1 Template:Unbulleted list citebundle

- ↑ "Christchurch mosque attack death toll rises". The Sydney Morning Herald. 2019-05-02. Archived from the original on 26 January 2024. Retrieved 2024-01-26.

- ↑ "NZ terror attack victims' age range 3–77". Dhaka Tribune. 17 March 2019. Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- ↑ Cite error: The named reference

rnz006was used but no text was provided for refs named (see the help page). - ↑ Chavez, Nicole; Regan, Helen; Sidhu, Sandi; Sanchez, Ray. "Suspect in New Zealand mosque shootings was prepared 'to continue his attack,' PM says". CNN. Archived from the original on 16 March 2019. Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- ↑ NZ Police v Tarrant, 2019 NZDC 4784 (16 March 2019).

- ↑ "Mosque attacks suspect gives 'white power' sign in Christchurch court". Axios. Archived from the original on 16 March 2019. Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- ↑ "New Zealand mosque attack suspect Brenton Tarrant grins in court". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 12 August 2020. Retrieved 2 April 2019.

- ↑ "Mental health tests for NZ attack suspect". BBC News. 4 April 2019. Archived from the original on 24 June 2020. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ↑ "Christchurch shooter: Brenton Tarrant complains about jail". News.com.au. 1 April 2019. Archived from the original on 5 September 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ↑ "Accused to face 50 murder charges, police confirm". Radio New Zealand. 4 April 2019. Archived from the original on 12 August 2020. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ↑ "Mental health tests for NZ attack suspect". BBC News. 4 April 2019. Archived from the original on 24 June 2020.

- ↑ "Accused mosque shooter now facing terrorism charge". Stuff. 21 May 2019. Archived from the original on 12 August 2020. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- ↑ "Man accused of Christchurch mosque shootings pleads not guilty to 51 murder charges". Stuff. 14 June 2019. Archived from the original on 24 July 2020. Retrieved 13 June 2019.

- ↑ "Christchurch mosque shooting trial delayed for Ramadan". Stuff. 12 September 2019. Archived from the original on 9 August 2020. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- ↑ Multiple sources:

- Bateman, Sophie (15 August 2019). "Alleged Christchurch shooter Brenton Tarrant sent seven letters from prison". Newshub. Archived from the original on 14 August 2019. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- Perry, Nick (14 August 2019). "Alleged Christchurch gunman sends letter from prison cell". The Washington Post. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 14 August 2019. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- "Officials admit letting accused Christchurch shooter send letter to supporter from prison". Brisbane Times. Associated Press and Stuff. 14 August 2019. Archived from the original on 12 August 2020. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- ↑ "Prison letters: Cabinet pushes ahead with law changes to Corrections Act". Radio New Zealand. 19 August 2019. Archived from the original on 12 August 2020. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- ↑ Sachdeva, Sam (20 August 2019). "Govt mulls law change after prisoner letter fiasco". Newsroom. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- ↑ "Christchurch gunman pleads guilty to 51 murders". BBC News. 25 March 2020. Archived from the original on 15 July 2020. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ↑ Bayer, Kurt; Leask, Anna (26 March 2020). "Christchurch mosque shootings: Brenton Tarrant's shock guilty plea to murders". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 20 August 2020. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- ↑ Bayer, Kurt (26 March 2020). "Shock guilty plea: Brenton Tarrant admits mosque shootings". Newstalk ZB. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- ↑ Bayer, Kurt (10 July 2020). "Christchurch mosque shooting: Border exceptions for victims based overseas to attend gunman's sentencing". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 10 July 2020. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- ↑ Andelane, Lana (13 July 2020). "Christchurch mosque shooting: Brenton Tarrant to represent himself at sentencing". Newshub. Archived from the original on 13 July 2020. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- ↑ Bayer, Kurt (13 July 2020). "Christchurch mosque shooting: Brenton Tarrant sacks lawyers, will represent himself at sentencing". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 13 July 2020. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- ↑ "Significantly fewer victims to attend Christchurch mosque gunman's sentencing due to Covid restrictions". Stuff. 18 August 2020. Archived from the original on 22 August 2020. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ↑ Leask, Anna (18 August 2020). "Christchurch mosque attacks: More details released about gunman's sentencing". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 18 August 2020. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ↑ Leask, Anna; Bayer, Kurt (27 August 2020). "Christchurch mosque attack sentencing: Brenton Tarrant will never be released from jail". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 27 August 2020. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- ↑ Graham-Mclay, Charlotte (27 August 2020). "Christchurch shooting: mosque gunman sentenced to life without parole". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 28 August 2020. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- ↑ "New Zealand court hears how mosque shooter planned deadly attacks". TRT World. 25 August 2020. Archived from the original on 26 August 2020. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- ↑ "Christchurch shooting: Gunman Tarrant wanted to kill 'as many as possible'". BBC News. 24 August 2020. Archived from the original on 25 August 2020. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- ↑ Multiple sources:

- Lourens, Marine (25 August 2020). "Applause as victim tells terrorist: 'You are the loser and we are the winners". Stuff. Archived from the original on 26 August 2020. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- "Christchurch mosque shooter sniggers as victim reads out his impact statement". 1 News. 25 August 2020. Archived from the original on 28 August 2020. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- Leask, Anna; Bayer, Kurt (26 August 2020). "Christchurch mosque attack sentencing: Victim's son describes Brenton Tarrant as trash who should be buried in a landfill". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 26 August 2020. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- Miller, Barbara; Ford, Mazoe (25 August 2020). "Christchurch mosque survivors and families stare down gunman Brenton Tarrant in sentencing hearing". ABC News. Archived from the original on 26 August 2020. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- ↑ Cite error: The named reference

Stuff last gasp2was used but no text was provided for refs named (see the help page). - ↑ R v Tarrant, 2020 NZHC 2192 (Christchurch High Court 27 August 2020).

- ↑ "Christchurch mosque attack: Brenton Tarrant sentenced to life without parole". No. 27 August 2020. BBC. Archived from the original on 9 August 2021. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

- ↑ Perry, Nick (23 August 2020). "Families confront New Zealand mosque shooter at sentencing". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 13 February 2023. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

- ↑ "The ins and outs of life without parole". Newswroom. 28 March 2019. Archived from the original on 28 August 2020. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- ↑ Maiden, Samantha (27 August 2020). "Mosque gunman Brenton Tarrant could serve out sentence in Australia, Scott Morrison reveals". The New Zealand Herald. ISSN 1170-0777. Archived from the original on 28 August 2020. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ↑ "Christchurch mosque shooting: Terrorist launches fresh legal challenge". The New Zealand Herald. 14 April 2021. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ↑ O'Callaghan, Jody (14 April 2021). "Christchurch mosque killer launches legal appeal over 'terrorist status'". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ↑ "New Zealand mosque shooter drops legal challenge over police conditions". Reuters. 24 April 2021. Archived from the original on 25 April 2021. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ↑ Cook, Charlotte (8 November 2021). "Christchurch mosque terrorist claims he pleaded guilty because of inhumane treatment in prison". Radio New Zealand. Archived from the original on 8 November 2021. Retrieved 9 November 2021.

- ↑ O'Callaghan, Jody (8 November 2021). "Victims' family anger over Christchurch shooting killer's plan to appeal". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 8 November 2021. Retrieved 9 November 2021.

- ↑ "Armed police guard mosques around New Zealand". Stuff (company). Archived from the original on 16 April 2022. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- ↑ Cooke, Henry; Kirk, Stacey (15 March 2019). "New Zealand officially on high terror alert, in wake of Christchurch terror attacks". Stuff (company). Archived from the original on 15 March 2019. Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- ↑ Edmunds, Susan (15 March 2019). "Air New Zealand cancels flights, offers 'flexibility'". Stuff (company). Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- ↑ "Parliament security increased while security threat level high". Radio New Zealand. Archived from the original on 19 March 2019. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- ↑ Miller, Tim (16 March 2019). "Neighbours say Tarrant kept to himself, liked to travel". Otago Daily Times. Archived from the original on 8 July 2019. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- ↑ "Christchurch mosque shootings: Accused gunman Brenton Tarrant was a 'model tenant' in Dunedin". The New Zealand Herald. 18 March 2019. Archived from the original on 23 June 2019. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- ↑ Kidd, Rod; Miller, Tim (15 March 2019). "Part of Dunedin street evacuated after report city was original target". Otago Daily Times. Archived from the original on 15 March 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- ↑ "Mosque shootings: AOS on Dunedin street after report city was original target". The New Zealand Herald. 15 March 2019. ISSN 1170-0777. Archived from the original on 22 May 2019. Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- ↑ "New Zealand officially on high terror alert, in wake of Christchurch terror attacks". Stuff (company). Archived from the original on 15 March 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- ↑ Multiple sources:

- "Live stream: 1 News at 6 pm". 15 March 2019. Archived from the original on 30 January 2019. Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- "PM on mosque shooting: 'One of New Zealand's darkest days'". Newstalk ZB. 15 March 2019. Archived from the original on 12 July 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- "Christchurch mosque shootings: 'This can only be described as a terrorist attack' – PM Jacinda Ardern". Radio New Zealand. 15 March 2019. Archived from the original on 20 March 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- ↑ "Three in custody after 49 killed in Christchurch mosque shootings". Stuff (company). Archived from the original on 15 March 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- ↑ Wahlquist, Calla (19 March 2019). "Ardern says she will never speak name of Christchurch suspect". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 19 March 2019. Retrieved 20 March 2019.

- ↑ "New Zealand Flag half-masting directive – Friday 15 20 March" (Press release). Ministry For Culture And Heritage. Archived from the original on 17 March 2019. Retrieved 17 March 2019 – via Scoop.

- ↑ "NZTA to replace GUN number plates for free". Stuff (company). 1 May 2019. Archived from the original on 16 May 2019. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- ↑ Multiple sources:

- "Christchurch mosque shooting: Police officers who apprehended alleged gunman named". RNZ. 10 December 2019. Archived from the original on 13 June 2020. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- Leask, Anna (16 October 2019). "Hero cops: Christchurch terror arrest officers' bravery recognised at national ceremony". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 16 October 2019. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- "Officers who captured Christchurch terrorist attack suspect awarded for their bravery". 1 News. 16 October 2019. Archived from the original on 16 October 2019. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- ↑ "PM designates Christchurch mosque shooter a 'terrorist entity'". MSN. Archived from the original on 21 October 2020. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ↑ Every-Palmer, S.; Cunningham, R.; Jenkins, M.; Bell, E. (23 June 2020). "The Christchurch mosque shooting, the media, and subsequent gun control reform in New Zealand: a descriptive analysis". Psychiatry, Psychology and Law. 28 (2): 274–285. doi:10.1080/13218719.2020.1770635. ISSN 1321-8719. PMC 8547820. PMID 34712096. S2CID 225699765.

- ↑ 189.0 189.1 Ellis, Gavin; Muller, Denis (2 July 2020). "The proximity filter: the effect of distance on media coverage of the Christchurch mosque attacks". Kōtuitui: New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences Online. 15 (2): 332–348. doi:10.1080/1177083X.2019.1705358.

- ↑ "Black Caps v Bangladesh test cancelled after gunmen attack Christchurch mosques". Stuff (company). Archived from the original on 15 March 2019. Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- ↑ "Bangladesh cricket team flees mosque shooting". City News 1130. Archived from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- ↑ "Cricketers escape NZ mosque shooting". Cricket Australia. Archived from the original on 9 June 2022. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- ↑ "Bangladesh tour of New Zealand called off after Christchurch terror attack". ESPNcricinfo. 15 March 2019. Archived from the original on 28 April 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- ↑ "Canterbury withdraw from final Plunket Shield match, handing CD title". Stuff. 16 March 2019. Archived from the original on 24 March 2019. Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- ↑ "Highlanders-Crusaders cancelled after massacre | Sporting News". www.sportingnews.com. Archived from the original on 24 March 2019. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ↑ "'Spill the Blood' band Slayer pulls out of Christchurch concert". Stuff (company). Archived from the original on 16 March 2019. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ↑ Multiple sources:

- Olito, Frank. "The internet is applauding a man's raw reaction to the New Zealand mass shooting after he laid flowers at a local mosque". INSIDER. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- "'We love you': mosques around world showered with flowers after Christchurch massacre". The Guardian. 16 March 2019. Archived from the original on 18 March 2019. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- "Hamilton mosque makes sure flowers live on". Stuff (company). Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- "Christchurch terror attack: How to support NZ's Muslim communities". The Spinoff. 16 March 2019. Archived from the original on 19 March 2019. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- ↑ Mahony, Maree (16 March 2019). "Christchurch mosque attacks: Mayor Lianne Dalziel says city turning to practical help". RNZ. Radio New Zealand. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- ↑ "Mass haka and waiata performed outside Christchurch mosque to honour shooting victims". The New Zealand Herald. 21 March 2019. Archived from the original on 21 March 2019. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- ↑ Hassan, Jennifer; Tamkin, Emily (18 March 2019). "The power of the haka: New Zealanders pay traditional tribute to mosque attack victims". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 19 March 2019. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- ↑ Multiple sources:

- "Mongrel Mob gang members to stand guard at local mosque, in support of Muslim Kiwis". Stuff (company). Archived from the original on 20 March 2019. Retrieved 21 March 2019.