Megalodon

| Megalodon | |

|---|---|

| |

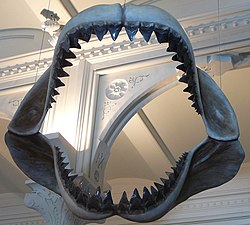

| Model of the jaws of the megalodon at the American Museum of Natural History | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Subphylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Subclass: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | O. megalodon

|

| Binomial name | |

| Otodus megalodon | |

Megalodon is a theoretically extinct species of shark and was the largest of all time, as far as we know. Its scientific name is Otodus megalodon (meaning "big mouth"). It lived from the early Miocene to the Pliocene epochs, 23 to 3.6 million years ago (mya). It is not closely related to the present-day great white shark.

Megalodon had teeth, which are among the largest ever found, over 18 cm (7.1 in) long. Nicolaus Steno was the first to recognize the teeth as those of a giant shark. Paleontologists calculate that the shark was up to 20 m (66 ft) long with average length of 17 meters (56 feet) It weighed up to 48-103 metric tons. Recent teeth have been found dating back to 11,000 years ago.[1]

Paleoecology[change | change source]

Fossil records of O. megalodon indicate that it occurred in deep to tropical latitudes.[2] Before the formation of the Isthmus of Panama, the seas were relatively warmer.[3] This would have made it possible for the species to live in all the oceans of the world.

O. megalodon lived in many marine environments (i.e. continental shelf waters,[4] coastal upwelling,[4] swampy coastal lagoons,[4] sandy littorals,[4] and offshore deep water environments),[5] and moved from place to place.[4] Adult O. megalodon were not abundant in shallow water environments,[4] and mostly lurked offshore. C. megalodon may have moved between coastal and oceanic waters, at different stages in its life.

Its prey[change | change source]

Megalodon hunted large and medium-sized whales, attacking the bony areas, such as chest, fins, or tail. This would stop the whale, or it could kill quickly with a fatal bite to the chest region. The megalodon bite is considered one of the strongest bites in the animal kingdom’s history.

Its great size,[6] high-speed swimming capability,[7] and powerful jaws coupled with formidable killing apparatus,[2][6] made it an apex predator eating a range of fauna.

Fossil evidence is that C. megalodon preyed on cetaceans (i.e., dolphins,[2] small whales,[4][8] and Odobenocetops,[9] and large whales,[10] (including sperm whales,[5][11] bowhead whales,[12] and rorquals[10][13] pinnipeds,[14] porpoises,[5] sirenians,[4][15] and giant sea turtles.[4]

Marine mammals were regular prey targets for megalodon. Many whale bones have been found with clear signs of large bite marks (deep gashes) made by teeth that match those of megalodon,[2][8] and various excavations have revealed megalodon teeth lying close to the chewed remains of whales,[2] and sometimes in direct association with them. Fossil evidence of interactions between megalodon and pinnipeds also exist. In one interesting observation, a 127 millimetres (5.0 in) megalodon tooth was found lying very close to a bitten earbone of a sea lion.[14]

Relationships[change | change source]

Megalodon is now considered to be a member of the family Otodontidae, genus Otodus.[16] Megalodon's older classification into Carcharodon was due to dental similarity with the great white shark. Most authors now think this is due to convergent evolution. The great white shark is more closely related to the extinct broad-toothed mako (Isurus hastalis) than to megalodon. The dentition in those two sharks is similar, whereas megalodon teeth have much finer serrations than great white shark teeth. The great white shark is more closely related to the mako shark (Isurus spp.), with a most recent common ancestor about 4 mya.[17] Those who still think megalodon and the great white shark are more closely related, argue that the differences between their dentition are minute and obscure.[2]: 23–25

References[change | change source]

- ↑ Jacoby D.M.P. et al 2015. Is the scaling of swim speed in sharks driven by metabolism?. Biology Letters 12 (10): [1]

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Klimley, Peter; Ainley, David 1996. Great White Sharks: the biology of Carcharodon carcharias. Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-415031-4

- ↑ Gillette, Lynett. "Winds of Change". San Diego Natural History Museum. Archived from the original on 2009-02-07. Retrieved 2012-04-04.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 Aguilera O. & E.R.D. (2004). "Giant-toothed White sharks and wide-toothed Mako (Lamnidae) from the Venezuela Neogene: their role in the Caribbean shallow-water fish assemblage". Caribbean Journal of Science. 40 (3): 362–368.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Renz, Mark 2002. Megalodon: hunting the hunter. PaleoPress. ISBN 0-9719477-0-8

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Wroe S. et al. 2008. Three-dimensional computer analysis of white shark jaw mechanics: how hard can a great white bite?. Journal of Zoology 276 (4): 336–342.

- ↑ Arnold, Caroline 2000. Giant Shark: Megalodon, prehistoric super predator. Houghton Mifflin. pp 18–19 ISBN 978-0-395-91419-9

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Bruner, J.C. (1997). "The Megatooth shark, Carcharodon megalodon: rough toothed, huge toothed". Mundo Marino Revista Internacional de Vida (Non-refereed). 5. Marina: 6–11. Archived from the original on 2015-07-16. Retrieved 2011-11-14.

- ↑ "Fact File: Odobenocetops". BBC. Retrieved 2008-03-21.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Morgan, Gary S. (1994). "Whither the giant white shark?". Paleontology Topics. Paleontological Research Institution.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ↑ "MEGALODON". Fossil Farm Museum of the Fingerlakes. Archived from the original on 2010-08-05. Retrieved 2010-07-01.

- ↑ deGruy, Michael (2006). Perfect Shark (TV-Series). UK: BBC.

- ↑ Godfrey, Stephen (2004). "The Ecphora: fascinating fossil finds" (PDF). Paleontology Topics. Calvert Marine Museum. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 October 2013. Retrieved 21 February 2010.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Kehe, Andy. "Bone apetite". Archived from the original on 18 May 2008. Retrieved 17 February 2011.

- ↑ Godfrey, Stephen (2007). "The Ecphora: shark-bitten sea cow rib" (PDF). Paleontology Topics. Calvert Marine Museum. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 October 2013. Retrieved 27 March 2010.

- ↑ Shimada, K.; Chandler, R. E.; Lam, O. L. T.; Tanaka, T.; Ward, D. J. (2016). "A new elusive otodontid shark (Lamniformes: Otodontidae) from the lower Miocene, and comments on the taxonomy of otodontid genera, including the 'megatoothed' clade". Historical Biology. 29 (5): 1–11. doi:10.1080/08912963.2016.1236795. S2CID 89080495.

- ↑ Ehret D. J.; Hubbell G.; Macfadden B. J. (2009). "Exceptional preservation of the white shark Carcharodon from the early Pliocene of Peru". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 29 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1671/039.029.0113. JSTOR 20491064. S2CID 129585445.