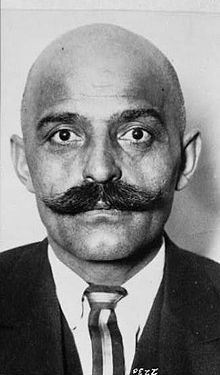

Gurdjieff

Gurdjieff | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | January 13, 1866 |

| Died | October 29, 1949 (aged 83) |

| Era | 20th-century |

| School | "Fourth Way" |

Main interests | Psychology, philosophy, science, ancient knowledge |

Influences | |

George Ivanovich Gurdjieff (13 January 1866 – 29 October 1949), usually called Gurdjieff, was a Greek- Armenian guru and writer.[1][2][3][4] He was an influential spiritual teacher of the first half of the 20th century. He was influenced by Sufi, Zen and Yoga mystics he met on his early travels.[5][6]

Gurdjieff taught that most people live their entire lives in a state of hypnotic "waking sleep":

- "Speaking frankly... contemporary man as we know him is nothing more than merely a clockwork mechanism, though of a very complex construction".[7]

- "A modern man lives in sleep, in sleep he is born and in sleep he dies".[6]p66

Gurdjieff developed a method for working towards a higher state of consciousness and achieving full human potential. He called this "The Work" or "The Method".[6][8]

Gurdjieff's method for awakening one's consciousness is different from that of the fakir, monk or yogi, so his discipline was called originally the "Fourth Way".[9]

At different times in his life, Gurdjieff started and closed various schools around the world to teach the work. He said that the teachings he brought to the West came from his own experiences and early travels. The teachings expressed the truth found in ancient religions. They were wisdom teachings relating to self-awareness in people's daily lives, and humanity's place in the universe.[6]

Gurdjieff's writings[change | change source]

- Gurdjieff G.I. 1950. Beelzebub's tales to his grandson: an objectively impartial criticism of the life of man. 3 vols, Routledge & Kegan Paul, London. 1973 reprint, E.P. Dutton, N.Y. ISBN 0-525-47348-3

- Gurdjieff G.I. 1957. The struggle of the magicians: scenario of the ballet. Stourton, Capetown. Very limited printing of ten copies.

- Gurdjieff G.I. 1963. Meetings with remarkable men. Routledge & Kegan Paul, London. ISBN 0 7100 7032 2. Gurdjieff's own autobiography

- Gurjieff G.I. 1975. Life is only real then, when "I am". Routledge & Kegan Paul, London.

Biographies of Gurdjieff[change | change source]

- Ouspensky P.D. 1950. In search of the miraculous: fragments of an unknown teaching. Routledge & Kegan Paul, London. "Substantially, this comprises Gurdjieff's direct speech, which Gurdjieff gratefully acknowledged". Moore's biography p403.

- Ouspensky P.D. 1957. The fourth way: a record of talks and answers to questions based on the teaching of G.I. Gurdjieff. Routledge & Kegan Paul, London. ISBN 0-7100-7256-2

- Anderson, Margaret 1962. The unknowable Gurdjieff. Routledge & Kegan Paul, London.

- Nott C.S. 1969. Journey through this world: meetings with Gurdjieff, Orage and Ouspensky. Routledge & Kegan Paul, London.

- Bennett J.G. 1973. Gurdjieff: making a new world. Routledge & Kegan Paul, London. ISBN 0 85500 019 8

- Bennett J.G. 1975. Witness: the autobiography of John Bennett. Turnstone, London. ISBN 0 85500 043 0. Recounts in some detail meetings with Gurdjieff and Ouspensky.

- Wilson, Colin 1980. G.I. Gurdjieff: the war against sleep. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-850-30225-7 Paperback reprint: 2005. London: Aeon Books. ISBN 978-1-904-65829-0

- Moore, James 1991. Gurdjieff: a biography. Element, Shaftesbury, Dorset. ISBN 1-86204-606-9

- Smoley R. & Kinney J. 2006. Hidden wisdom: a guide to the western inner traditions. Wheaton, Illinois: Quest Books. ISBN 978-0-8356-0844-2. Chapter 9 (The way of the sly man: the teachings of G.I. Gurdjieff) is an excellent introduction to Gurdjieff.

Film[change | change source]

There is a 1979 British film, Meetings with Remarkable Men, directed by Peter Brook. It is based on the book of the same name by Gurdjieff. It was shot on location in Afghanistan (except for dance sequences, which were filmed in England). It starred Terence Stamp as Prince Lubovedsky, and Dragan Maksimovic as the adult Gurdjieff. The film was entered into the 29th Berlin International Film Festival and nominated for the Golden Bear prize.

Footnotes[change | change source]

- ↑ Pittman 2012, p. 223: "Though the long-held view is that Gurdjieff's mother was Armenian, Paul Taylor, on the basis of recent research, offers that Gurdjieff's mother's father was Greek (Taylor 2008)."

- ↑ Churton 2017, pp. 19–25: "Archival Records: ... One thing we can be reasonably certain of is that both Gurdjieff's parents were Greek. His mother's maiden name comes from the Greek Elephtheros, referring perhaps to the Greek Orthodox saint and martyr of this name as well as the ancient Greek word for freedom: a dangerous surname to have in Turkey in the wake of the bloody 1866–69 Cretan revolt against Turkish rule. Gurdjieff's mother's father Elepheriadis (Greek again) was married to Sophia, whose name was obviously Greek but who was nicknamed in her capacity as midwife padji, Turkish for "sister," a clue as to her birthplace. ... It is quite possible that Ivan met the Greek Evdokia in Alexandropol's substantial Greek quarter, known as Urmonts, which is recorded as having 363 households during the period when Gurdjieff's cousin, the sculptor Sergei Merkurov's grandfather built a house in Alexandropol (sometime between 1858 and 1869; accounts differ). Merkurov's family was among a hundred other Greek families who migrated from western Armenia (far-east Turkey), specifically the Vilayet of Trebizond in the period before the Russo-Turkish war of 1877–78. Grandfather Merkurov, an architect, would build Alexandropol's Greek Orthodox church, dedicated to Saint George (destroyed by earthquake in 1926)."

- ↑ Lipsey 2019, pp. 11, 316: "In his major book, Beelzebub's Tales to His Grandson (which developed across multiple languages from the mid-1920s through to its English-language publication in 1950), Gurdjieff was ferociously satirical where ancient Greek culture was concerned—though he was born to Greek parents and spoke Greek from his earliest days (as well as Armenian, and soon Russian and Turkish).15 ... 15. It will come as a surprise to readers familiar with the Gurdjieff legacy that both of his parents were Greek; the assumption has long been that his mother, Evdokia, was Armenian."

- ↑ Taylor 2020, pp. 10–15: "Alexandropol records have Ivan's wife as Evdokia Elepterovna, but on Ivan's death announcement, 25 June 1918, her name is given as M[unreadable] Kalerovna. The patronymic Kalerovna is given to Evdokia also on an 1885 document, and the French death notice of Gurdjieff's mother has "Evdoki Kaleroff" as her name, but I find the name Kaler only in Tyrol records from the fifteenth century. I am tempted to believe that Kaler reflects the Greek kalos "good, beautiful." The given and surnames of Gurdjieff's mother have semantic convergences, since Greek kalos "good" is compatible in meaning with Greek Eudoxia "Woman of Good Reputation." Since married women take their husband's family name almost always, I wonder why she was not identified as Evdokia Gurdjieff, as Gurdjieff's wife was identified on her travel documents. In a Church Slavonic register, Ivan and his wife are identified as Orthodox Christians. Gurdjieff's grandmother on his mother's side, Sophia, nicknamed Padji ("sister" in Turkish) was a well-regarded midwife who did not speak a word of Russian. His grandfather on his mother's side was Elepheriadis, a distinctly Greek form. Though Evdokia was thought by many to be Armenian, her name, Евдокия, is a Cyrillic form of Greek Eudoxia ("good thought"). The French form of the name on her death certificate is Eudoxie. Gurdjieff, who gave his mother's name to his youngest daughter, pronounced it in Russian fashion Yevdokeeya with stress on the penultimate syllable. If it seems odd that an Armenian woman would carry a Greek name, it is apparent that that Gurdjieff's mother was Greek as well as his father, confirming Gurdjieff's frequent assertion that his mother tongue was Greek. Gurdjieff's German papers, which he carried during the Second World War, identified him as Greek."

- ↑ Gurdjieff G.I. 1963. Meetings with remarkable men. Routledge & Kegan Paul, London. ISBN 0-7100-7032-2

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Ouspensky, P.D. (1977). In search of the miraculous. pp. 312–313. ISBN 0-15-644508-5.

- ↑ Gurdjieff G.I. 1950. Beelzebub's tales to his grandson: an objectively impartial criticism of the life of man. Routledge & Kegan Paul, London, vol 3, p399.

- ↑ Nott, C.S. (1961). Teachings of Gurdjieff : a pupil's journal: an account of some years with G.I. Gurdjieff and A.R. Orage in New York and at Fontainbleau-Avon. Routledge and Kegan Paul, London. ISBN 0-7100-8937-6.

- ↑ Gurdjieff International Review

References[change | change source]

- Churton, Tobias (2017). Deconstructing Gurdjieff: Biography of a Spiritual Magician. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-62055-639-9.

- Lipsey, Roger (2019). Gurdjieff Reconsidered: The Life, the Teachings, the Legacy. Shambhala Publications. ISBN 978-1-61180-451-5.

- Pittman, Michael S. (2012). Classical Spirituality in Contemporary America: The Confluence and Contribution of G.I. Gurdjieff and Sufism. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4411-8545-7.

- Taylor, Paul Beekman (2020). G.I.Gurdjieff: A Life. Eureka Editions. ISBN 978-94-92590-15-2.