Hepatitis C

The English used in this April 2012 may not be easy for everybody to understand. |

| Hepatitis C | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

| |

| ICD-10 | B17.1, B18.2 |

| ICD-9 | 070.70,070.4, 070.5 |

| OMIM | 609532 |

| DiseasesDB | 5783 |

| MedlinePlus | 000284 |

| eMedicine | med/993 ped/979 |

| MeSH | D006526 |

Hepatitis C is an infection that primarily affects the liver. The hepatitis C virus (HCV) causes this disease.[1] Hepatitis C often has no symptoms, but chronic infection can lead to scarring of the liver, and after many years to cirrhosis. In some cases, people with cirrhosis also have liver failure, liver cancer, or very swollen veins of the esophagus and stomach, which can result in bleeding to death.[1]

People get hepatitis C primarily by blood-to-blood contact from intravenous drug use, nonsterile medical equipment, and blood transfusions. An estimated 130–170 million people worldwide have hepatitis C. Scientists began investigating HCV in the 1970s, and confirmed that it exists in 1989.[2] It is not known to cause disease in other animals.

Peginterferon and ribavirin are the standard medications for HCV. Between 50-80% of people treated are cured. People who develop cirrhosis or liver cancer might need a liver transplant, but the virus usually recurs after a transplant.[3] There is no vaccine for hepatitis C.

Signs and symptoms

Hepatitis C causes acute symptoms in just 15% of cases.[4] Symptoms are more often mild and vague, including a decreased appetite, fatigue, nausea, muscle or joint pains, and weight loss.[5] Only a few cases of acute infection are associated with jaundice.[6] The infection resolves without treatment in 10-50% of people, and in young females more often than others.[6]

Chronic infection

Eighty percent of people exposed to the virus develop a chronic infection.[7] Most experience minimal or no symptoms during the first decades of the infection,[8] although chronic hepatitis C can be associated with fatigue.[9] Hepatitis C is the primary cause of cirrhosis and liver cancer among people infected for many years.[3] Between 10–30% of people infected over 30 years develop cirrhosis.[3][5] Cirrhosis is more common in people also infected with hepatitis B or HIV, alcoholics, and males.[5] People who develop cirrhosis have twenty times greater risk of liver cancer, a rate of 1-3% per year.[3][5] For alcoholics, the risk is 100 times greater.[10] Hepatitis C is the cause of 27% of cirrhosis cases and 25% of liver cancer cases.[11]

Liver cirrhosis can lead to high blood pressure in the veins connecting to the liver, accumulation of fluid in the abdomen, easy bruising or bleeding, enlarged veins, especially in the stomach and esophagus, jaundice (a yellowing of the skin), and brain damage.[12]

Effects outside the liver

Hepatitis C is also rarely associated with Sjögren's syndrome (an autoimmune disorder), a lower than normal number of blood platelets, chronic skin disease, diabetes, and non-Hodgkin lymphomas.[13][14]

Cause

The hepatitis C virus is a small, enveloped, single-stranded, positive-sense RNA virus.[3] It is a member of thehepacivirus genus in the family Flaviviridae.[9] There are seven major genotypes of HCV.[15] In the United States, genotype 1 causes 70% of cases, genotype 2 causes 20%, and each of the other genotypes causes 1%.[5] Genotype 1 is also the most common in South America and Europe.[3]

Transmission

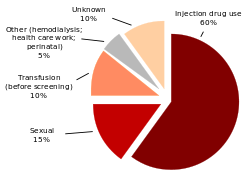

The primary method of transmission in the developed world is intravenous drug use (IDU). In the developing world the main methods are blood transfusions and unsafe medical procedures[16] The cause of transmission remains unknown in 20% of cases;[17] but many of these cases are likely due to IDU.[6]

Intravenous drug use

IDU is a major risk factor for hepatitis C in many parts of the world.[18] A review of 77 countries shows that 25 have rates of hepatitis C in the intravenous drug user population of between 60% and 80%, including the United States[7] and China.[18] Twelve countries have rates greater than 80%.[7] As many as ten million intravenous drug users are infected with hepatitis C; China (1.6 million), the United States (1.5 million), and Russia (1.3 million) have the highest totals.[7] Rates of hepatitis C among prison inmates in the United States are ten to twenty times that of the rates of the general population, which these studies attribute to high-risk behavior such as IDU and tattooing with nonsterile equipment.[19][20]

Healthcare exposure

Blood transfusions, blood products, and organ transplants without HCV screening create significant risk for infection.[5] The United States instituted universal screening in 1992. Since then the infection rate has decreased from a rate of one in 200 per units of blood[21] to one in 10,000 to 10,000,000 per units of blood.[6][17] This low risk remains because there is a period of about 11–70 days between a potential blood donor acquiring hepatitis C and their blood testing positive.[17] Some countries still do not screen for hepatitis C due to the cost.[11]

A person who has a needle stick injury from a person with HCV has about a 1.8% chance of then getting the disease.[5] The risk is greater if the needle used is hollow and the puncture wound is deep.[11] There is a risk from mucus exposures to blood; but this risk is low, and there is no risk if blood exposure occurs on intact skin.[11]

Hospital equipment also transmits hepatitis C including: reuse of needles and syringes, multiple-use medication vials, infusion bags, and nonsterile surgical equipment.[11] Poor standards in medical and dental facilities are the main cause of the spread of HCV in Egypt, the country with highest rate of infection in the world.[22]

Sexual intercourse

Whether hepatitis C can be transmitted through sex is not known.[23] While there is an association between high-risk sexual activity and hepatitis C, it is not clear whether transmission of the disease is due to drug use which was not mentioned or sex itself.[5] The evidence supports there being no risk for heterosexual couples who do not have sex with other people.[23] Sexual practices that involve high levels of trauma to the inner lining of the anal canal, such as anal penetration, or that occur when there is a also sexually transmitted infection, including HIV or genital ulceration, do present a risk.[23] The United States government recommends condom use only to prevent hepatitis C transmission in people with multiple partners.[24]

Body piercings

Tattooing is associated with a two to three times increased risk of hepatitis C.[25] This can be due to nonsterile equipment or contamination of the dyes used.[25] Tattoos or body piercings performed before the mid-1980s or by nonprofessionally are of particular concern, since sterile techniques in such settings may be poor. The risk also appears to be greater for larger tattoos.[25] Nearly half of prison inmates share unsterilized tattooing equipment.[25] It is rare for tattoos in a licensed facility to be directly associated with HCV infection.[26]

Contact with blood

Personal-care items such as razors, toothbrushes, and manicure or pedicure equipment can come into contact with blood. Sharing them risks exposure to HCV.[27][28] People should be careful with cuts and sores or other bleeding.[28] HCV does not spread through casual contact, such as hugging, kissing, or sharing eating or cooking utensils.[28]

Transmission from mother to child

Transmission of hepatitis C from an infected mother to her child occurs in less than 10% of pregnancies.[29] There are no measures that alter this risk.[29] Transmission can occur during pregnancy and at delivery.[17] A long labor is associated with a greater risk of transmission.[11] There is no evidence that breast-feeding spreads HCV; however, an infected mother should avoid breastfeeding if her nipples are cracked and bleeding,[30] or her viral loads are high.[17]

Diagnosis

Diagnostic tests for hepatitis C include: HCV antibody, ELISA, Western blot, and quantitative HCV RNA.[5] Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) can detect HCV RNA one to two weeks after infection, while antibodies can take substantially longer to form and reveal themselves.[12]

Chronic hepatitis C is an infection with the hepatitis C virus that persists for more than six months based on the presence of its RNA.[8] Because chronic infections typically have no symptoms for decades,[8] clinicians commonly discover it through liver function tests or during routine screening of high risk people. Testing cannot distinguish between acute and chronic infections.[11]

Blood testing

Hepatitis C testing typically begins with blood tests to detect the presence of antibodies to the HCV using an enzyme immunoassay.[5] If this test is positive, a second test is performed to verify the immunoassay and to determine the severity.[5] A recombinant immunoblot assay verifies the immunoassay, and an HCV RNA polymerase chain reaction determines the severity.[5] If there are no RNA and the immunoblot is positive, the person had a previous infection but cleared it either with treatment or spontaneously; if the immunoblot is negative, the immunoassay was wrong.[5] It takes six to eight weeks following infection before the immunoassay tests positive.[9]

Liver enzymes are variable during the initial part of the infection;[8] on average they begin to rise at seven weeks after infection.[9] Liver enzymes are poorly related to disease severity.[9]

Biopsy

Liver biopsies can determine the degree of liver damage, but there are risks from the procedure.[3] The typical changes a biopsy detects are lymphocytes within the liver tissue, lymphoid follicles in the portal triad, and changes to the bile ducts.[3] There are a number of blood tests available that try to determine the degree of damage and alleviate the need for biopsy.[3]

Screening

As few as 5–50% of people infected in the United States and Canada are aware of their status.[25] Testing is recommended for people at high risk, which includes people with tattoos.[25] Screening is also recommended in people with elevated liver enzymes as this is frequently the only sign of chronic hepatitis.[31] Routine screening is not recommended in the United States.[5]

Prevention

As of 2011, no vaccine exists for hepatitis C. Vaccines are under development and some have shown encouraging results.[32] A combination of preventive strategies, such as needle exchange programs and treatment for substance abuse, decrease the risk of hepatitis C in intravenous drug users by about 75%.[33] Screening blood donors is important at a national level, as is adhering to universal precautions within healthcare facilities.[9] In countries where there is an insufficient supply of sterile syringes, care providers should give medications orally rather than via injection.[11]

Treatment

HCV induces chronic infection in 50–80% of infected persons. Approximately 40-80% of these cases clear with treatment.[34][35] In rare cases, infection can clear without treatment.[6] People with chronic hepatitis C should avoid alcohol and medications toxic to the liver,[5] and should be vaccinated for hepatitis A and hepatitis B.[5] People with cirrhosis should have ultrasound tests for liver cancer.[5]

Medications

People with proven HCV infection liver abnormalities should seek treatment.[5] Current treatment is a combination of pegylated interferon and the antiviral drug ribavirin for 24 or 48 weeks, depending on HCV type.[5] Improved outcomes occur for 50–60% of people treated.[5] Combining either boceprevir or telaprevir with ribavirin and peginterferon alfa improves antiviral response for hepatitis C genotype 1.[36][37][38] Side effects with treatment are common; half of people treated get flu like symptoms, and a third experience emotional problems.[5] Treatment during the first six months is more effective than after hepatitis C becomes chronic.[12] If a person develops a new infection and it has not cleared after eight to twelve weeks, 24 weeks of pegylated interferon is recommended.[12] For people with thalassemia (a blood disorder), ribavirin appears to be useful, but increases the need for transfusions.[39] Proponents claim several alternative therapies to be helpful for hepatitis C including milk thistle, ginseng, and colloidal silver.[40] However, no alternative therapy has been shown to improve outcomes in hepatitis C, and no evidence exists that alternative therapies have any effect on the virus at all.[40][41][42]

Likely outcome

Responses to treatment vary by genotype. Sustained response is about 40-50% in people with HCV genotype 1 with 48 weeks of treatment.[3] Sustained response occurs in 70-80% of people with HCV genotypes 2 and 3 with 24 weeks of treatment.[3] Sustained response is about 65% in people with genotype 4 with 48 weeks of treatment. The evidence for treatment in genotype 6 disease is currently sparse, and the evidence that exists is for 48 weeks of treatment at the same doses as genotype 1 disease.[43]

Epidemiology

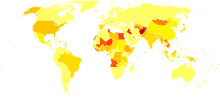

no data <10 10-15 15-20 20-25 25-30 30-35 | 35-40 40-45 45-50 50-75 75–100 >100 |

Between 130 and 170 million people, or ~3% of the world's population, are living with chronic hepatitis C.[44] Between 3–4 million people are infected per year, and more than 350,000 people die yearly from hepatitis C-related diseases.[44] Rates have increased substantially in the 20th century due to a combination of IDU and intravenous medication or nonsterilized medical equipment.[11]

In the United States, about 2% of people have hepatitis C,[5] with 35,000 to 185,000 new cases a year. Rates have decreased in the West since the 1990s due to improved blood screening before transfusion.[12] Annual deaths from HCV in the United States range from 8,000 to 10,000. Expectations are that this mortality rate will increase as people infected by transfusion before HCV testing become ill and die.[45]

Infection rates are higher in some countries in Africa and Asia.[46] Countries with very high rates of infection include Egypt (22%), Pakistan (4.8%) and China (3.2%).[44] The high rate in Egypt is linked to a now-discontinued mass-treatment campaign for schistosomiasis, using improperly sterilized glass syringes.[11]

History

In the mid-1970s, Harvey J. Alter, Chief of the Infectious Disease Section in the Department of Transfusion Medicine at the National Institutes of Health, and his research team demonstrated that most post-blood transfusion hepatitis cases were not due to hepatitis A or B viruses. Despite this discovery, international research efforts to identify the virus failed for the next decade. In 1987, Michael Houghton, Qui-Lim Choo, and George Kuo at Chiron Corporation, collaborating with Dr. D.W. Bradley from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, used a new molecular cloning approach to identify the unknown organism and develop a diagnostic test.[47] In 1988, Alter confirmed the virus by verifying its presence in a panel of non A non B hepatitis specimens. In April 1989, the discovery of HCV was published in two articles in the journal Science.[48][49] The discovery led to significant improvements in diagnosis and improved antiviral treatment.[47] In 2000, Drs. Alter and Houghton were honored with the Lasker Award for Clinical Medical Research for "pioneering work leading to the discovery of the virus that causes hepatitis C and the development of screening methods that reduced the risk of blood transfusion-associated hepatitis in the U.S. from 30% in 1970 to virtually zero in 2000."[50]

Chiron filed for several patents on the virus and its diagnosis.[51] A competing patent application by the CDC was dropped in 1990 after Chiron paid $1.9 million to the CDC and $337,500 to Bradley. In 1994, Bradley sued Chiron, seeking to invalidate the patent, have himself included as a coinventor, and receive damages and royalty income. He dropped the suit in 1998 after losing before an appeals court.[52]

Society and culture

The World Hepatitis Alliance coordinates World Hepatitis Day, held every year on July 28.[53] The economic costs of hepatitis C are significant both to the individual and to society. In the United States the average lifetime cost of the disease was estimated at 33,407 USD in 2003,[54] with the cost of a liver transplant approximately 200,000 USD as of 2011.[55] In Canada the cost of a course of antiviral treatment was as high as 30,000 CAD in 2003,[56] while the United States costs are between 9,200 and 17,600 in 1998 USD.[54] In many areas of the world people are unable to afford treatment with antivirals because they lack insurance coverage or the insurance they have will not pay for antivirals.[57]

Research

As of 2011, about one hundred medications are in development for hepatitis C.[55] These medicines include vaccines to treat hepatitis, immunomodulators, and cyclophilin inhibitors.[58] These potentially new treatments have come about due to a better understanding of the hepatitis C virus.[59]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Ryan KJ, Ray CG (editors), ed. (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. pp. 551–2. ISBN 0838585299.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help) - ↑ Houghton M (2009). "The long and winding road leading to the identification of the hepatitis C virus". Journal of Hepatology. 51 (5): 939–48. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2009.08.004. PMID 19781804.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 Rosen, HR (2011-06-23). "Clinical practice. Chronic hepatitis C infection" (PDF). The New England journal of medicine. 364 (25): 2429–38. PMID 21696309.

- ↑ Maheshwari, A (2008-07-26). "Acute hepatitis C.". Lancet. 372 (9635): 321–32. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61116-2. PMID 18657711.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 5.13 5.14 5.15 5.16 5.17 5.18 5.19 5.20 5.21 Wilkins, T (2010-06-01). "Hepatitis C: diagnosis and treatment". American family physician. 81 (11): 1351–7. PMID 20521755.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Advances in Treatment, Promise for the Future. Springer Verlag. 2011. p. 4. ISBN 9781461411918.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Nelson, PK (2011-08-13). "Global epidemiology of hepatitis B and hepatitis C in people who inject drugs: results of systematic reviews". Lancet. 378 (9791): 571–83. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61097-0. PMID 21802134.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Advances in Treatment, Promise for the Future. Springer Verlag. 2011. pp. 103–104. ISBN 9781461411918.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 Dolin, [edited by] Gerald L. Mandell, John E. Bennett, Raphael (2010). Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's principles and practice of infectious diseases (7th ed. ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. pp. Chapter 154. ISBN 978-0443068393.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help);|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Mueller, S (2009-07-28). "Alcoholic liver disease and hepatitis C: a frequently underestimated combination". World journal of gastroenterology : WJG. 15 (28): 3462–71. PMID 19630099.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑ 11.00 11.01 11.02 11.03 11.04 11.05 11.06 11.07 11.08 11.09 Alter, MJ (2007-05-07). "Epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection". World journal of gastroenterology : WJG. 13 (17): 2436–41. PMID 17552026.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 Ozaras, R (2009 Apr). "Acute hepatitis C: prevention and treatment". Expert review of anti-infective therapy. 7 (3): 351–61. PMID 19344247.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑ Zignego AL, Ferri C, Pileri SA, Caini P, Bianchi FB (2007). "Extrahepatic manifestations of Hepatitis C Virus infection: a general overview and guidelines for a clinical approach". Digestive and Liver Disease. 39 (1): 2–17. doi:10.1016/j.dld.2006.06.008. PMID 16884964.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Louie, KS (2011 Jan). "Prevalence of thrombocytopenia among patients with chronic hepatitis C: a systematic review". Journal of viral hepatitis. 18 (1): 1–7. PMID 20796208.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑ Nakano T, Lau GM, Lau GM, Sugiyama M, Mizokami M (2011). "An updated analysis of hepatitis C virus genotypes and subtypes based on the complete coding region". Liver Int. doi:10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02684.x. PMID 22142261.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Maheshwari, A (2010 Feb). "Management of acute hepatitis C.". Clinics in liver disease. 14 (1): 169–76, x. PMID 20123448.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 Pondé, RA (2011 Feb). "Hidden hazards of HCV transmission". Medical microbiology and immunology. 200 (1): 7–11. PMID 20461405.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑ 18.0 18.1 Xia, X (2008 Oct). "Epidemiology of HCV infection among injection drug users in China: systematic review and meta-analysis". Public health. 122 (10): 990–1003. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2008.01.014. PMID 18486955.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑ Imperial, JC (2010 Jun). "Chronic hepatitis C in the state prison system: insights into the problems and possible solutions". Expert review of gastroenterology & hepatology. 4 (3): 355–64. PMID 20528122.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ↑ Vescio, MF (2008 Apr). "Correlates of hepatitis C virus seropositivity in prison inmates: a meta-analysis". Journal of epidemiology and community health. 62 (4): 305–13. PMID 18339822.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑ Marx, John (2010). Rosen's emergency medicine: concepts and clinical practice 7th edition. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby/Elsevier. p. 1154. ISBN 9780323054720.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ↑ "Highest Rates of Hepatitis C Virus Transmission Found in Egypt". Al Bawaba. 2010-08-09. Retrieved 2010-08-27.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Tohme RA, Holmberg SD (2010). "Is sexual contact a major mode of hepatitis C virus transmission?". Hepatology. 52 (4): 1497–505. doi:10.1002/hep.23808. PMID 20635398.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ↑ "Hepatitis C Group Education Class". United States Department of Veteran Affairs.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 25.4 25.5 Jafari, S (2010 Nov). "Tattooing and the risk of transmission of hepatitis C: a systematic review and meta-analysis" (PDF). International journal of infectious diseases : IJID : official publication of the International Society for Infectious Diseases. 14 (11): e928-40. PMID 20678951.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑ "Hepatitis C" (PDF). Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ↑ Lock G, Dirscherl M, Obermeier F; et al. (2006). "Hepatitis C —contamination of toothbrushes: myth or reality?". J. Viral Hepat. 13 (9): 571–3. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2893.2006.00735.x. PMID 16907842.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 "Hepatitis C". FAQ – CDC Viral Hepatitis. Retrieved 2 Jan 2012.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Lam, NC (2010-11-15). "Caring for pregnant women and newborns with hepatitis B or C.". American family physician. 82 (10): 1225–9. PMID 21121533.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑ Mast EE (2004). "Mother-to-infant hepatitis C virus transmission and breastfeeding". Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 554: 211–6. PMID 15384578.

- ↑ Senadhi, V (2011 Jul). "A paradigm shift in the outpatient approach to liver function tests". Southern medical journal. 104 (7): 521–5. PMID 21886053.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ↑ Halliday, J (2011 May). "Vaccination for hepatitis C virus: closing in on an evasive target". Expert review of vaccines. 10 (5): 659–72. doi:10.1586/erv.11.55. PMID 21604986.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑ Hagan, H (2011-07-01). "A systematic review and meta-analysis of interventions to prevent hepatitis C virus infection in people who inject drugs". The Journal of infectious diseases. 204 (1): 74–83. PMID 21628661.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑ Torresi, J (2011 Jun). "Progress in the development of preventive and therapeutic vaccines for hepatitis C virus". Journal of hepatology. 54 (6): 1273–85. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2010.09.040. PMID 21236312.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑ Ilyas, JA (2011 Aug). "An overview of emerging therapies for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C.". Clinics in liver disease. 15 (3): 515–36. PMID 21867934.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑ Foote BS, Spooner LM, Belliveau PP (2011). "Boceprevir: a protease inhibitor for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C". Ann Pharmacother. 45 (9): 1085–93. doi:10.1345/aph.1P744. PMID 21828346.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Smith LS, Nelson M, Naik S, Woten J (2011). "Telaprevir: an NS3/4A protease inhibitor for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C". Ann Pharmacother. 45 (5): 639–48. doi:10.1345/aph.1P430. PMID 21558488.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Ghany MG, Nelson DR, Strader DB, Thomas DL, Seeff LB (2011). "An update on treatment of genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C virus infection: 2011 practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases". Hepatology. 54 (4): 1433–44. doi:10.1002/hep.24641. PMC 3229841. PMID 21898493.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Alavian SM, Tabatabaei SV (2010). "Treatment of chronic hepatitis C in polytransfused thalassaemic patients: a meta-analysis". J. Viral Hepat. 17 (4): 236–44. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2893.2009.01170.x. PMID 19638104.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ↑ 40.0 40.1 Hepatitis C and CAM: What the Science Says. NCCAM March 2011. (Retrieved 07 March 2011)

- ↑ Liu, J (2003 Mar). "Medicinal herbs for hepatitis C virus infection: a Cochrane hepatobiliary systematic review of randomized trials". The American journal of gastroenterology. 98 (3): 538–44. PMID 12650784.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑ Rambaldi, A (2007-10-17). "Milk thistle for alcoholic and/or hepatitis B or C virus liver diseases". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (4): CD003620. PMID 17943794.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑ Fung J, Lai CL, Hung I; et al. (2008). "Chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 6 infection: response to pegylated interferon and ribavirin". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 198 (6): 808–12. doi:10.1086/591252. PMID 18657036.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 "WHO Hepatitis C factsheet". 2011. Retrieved 2011-07-13.

- ↑ Colacino, ed. by J. M. (2004). Hepatitis prevention and treatment. Basel: Birkhäuser. p. 32. ISBN 9783764359560.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑ al.], edited by Gary W. Brunette ... [et. CDC health information for international travel : the Yellow Book 2012. New York: Oxford University. p. 231. ISBN 9780199769018.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ↑ 47.0 47.1 Boyer, JL (2001). Liver cirrhosis and its development: proceedings of the Falk Symposium 115. Springer. pp. 344. ISBN 9780792387602.

- ↑ Choo QL, Kuo G, Weiner AJ, Overby LR, Bradley DW, Houghton M (1989). "Isolation of a cDNA clone derived from a blood-borne non-A, non-B viral hepatitis genome". Science. 244 (4902): 359–62. doi:10.1126/science.2523562. PMID 2523562.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Kuo G, Choo QL, Alter HJ; et al. (1989). "An assay for circulating antibodies to a major etiologic virus of human non-A, non-B hepatitis". Science. 244 (4902): 362–4. doi:10.1126/science.2496467. PMID 2496467.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Winners Albert Lasker Award for Clinical Medical Research, The Lasker Foundation. Retrieved 20 February 2008.

- ↑ Houghton, M., Q.-L. Choo, and G. Kuo. NANBV Diagnostics and Vaccines. European Patent No. EP-0-3 18-216-A1. European Patent Office (filed 18 November 1988, published 31 May 1989).

- ↑ Wilken, Judge. "United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit". United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit. Retrieved 11 January 2012.

- ↑ Eurosurveillance editorial, team (2011-07-28). "World Hepatitis Day 2011". Euro surveillance : bulletin europeen sur les maladies transmissibles = European communicable disease bulletin. 16 (30). PMID 21813077.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 Wong, JB (2006). "Hepatitis C: cost of illness and considerations for the economic evaluation of antiviral therapies". PharmacoEconomics. 24 (7): 661–72. PMID 16802842.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 El Khoury, A. C. (1 December 2011). "Economic burden of hepatitis C-associated diseases in the United States". Journal of Viral Hepatitis. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2893.2011.01563.x.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑ "Hepatitis C Prevention, Support and Research ProgramHealth Canada". Public Health Agency of Canada. 2003. Retrieved 10 January 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Zuckerman, edited by Howard Thomas, Stanley Lemon, Arie (2008). Viral Hepatitis (3rd ed. ed.). Oxford: John Wiley & Sons. p. 532. ISBN 9781405143882.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help);|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Ahn, J (2011 Aug). "Hepatitis C therapy: other players in the game". Clinics in liver disease. 15 (3): 641–56. doi:10.1016/j.cld.2011.05.008. PMID 21867942.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑ Vermehren, J (2011 Feb). "New HCV therapies on the horizon". Clinical microbiology and infection : the official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. 17 (2): 122–34. PMID 21087349.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)