Pseudomonas

| Pseudomonas | |

|---|---|

| |

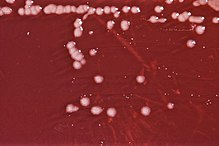

| P. aeruginosa colonies on an agar plate | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Phylum: | Pseudomonadota |

| Class: | Gammaproteobacteria |

| Order: | Pseudomonadales |

| Family: | Pseudomonadaceae |

| Genus: | Pseudomonas Migula 1894 |

| Type species | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | |

| Species | |

|

See text. | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Pseudomonas is a gram-negative bacteria. It is a genus belonging to the Pseudomonadaceae family. There are about 144 species in this genus.[2] Most of the Pseudomonas species are saprotrophic, meaning they release enzymes that break down big substances into small ones.

History[change | change source]

Pseudomonas is one of the earliest found bacteria. It was first called 'Bacterium aeruginosm' by Schroter in 1872. However, in 1894, German botanist Walter Migula classified it as Pseudomonas aeruginosa. In Greek, pseudo means false and monas means “unit”.[3] This bacteria is associated with many chronic infections and is considered dangerous due to its resistance to many antibiotics.[4] There has been an increase in the number of species discovered year by year. In 2013, 10 species have been found and 6 more in the subsequent year.[5] Pseudomonas was well-classified 100 years later by a Canadian scientist, Roger Stanier. [6] The classification was based on the physiological and biochemical properties.[5]

Phylogeny[change | change source]

The basic tool which is used to classify Pseudomonas is the 16S rRNA gene. [7] However, it is hard to differentiate closely related Pseudomonas species, thus genes such as atpD, gyrB, rpoB, recA, and rpoD are also used in the taxonomy of Pseudomonas.[8]

Using gyrB and rpoD in phylogenetic analysis, Pseudomonas came from two predominant clusters; intrageneric cluster I (IGC I) and intrageneric cluster II (IGC II).[9]

IGC I consists of two sub clusters, the ‘Pseudomonas aeruginosa complex’ comprises of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Pseudomonas alcaligenes, Pseudomonas citronellolis, Pseudomonas mendocina, Pseudomonas oleovorans and Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes, and the ‘Pseudomonas stutzeri complex’, comprises of Pseudomonas balearica and Pseudomonas stutzeri.

IGC II consists of three subclusters, the ‘Pseudomonas syringae complex’, the ‘Pseudomonas fluorescens complex’ and the ‘Pseudomonas putida complex’. The ‘Pseudomonas syringae complex’ are phytopathogens and pathovars. The former encompasses Pseudomonas amygdali, Pseudomonas caricapapayae, Pseudomonas cichorii, Pseudomonas ficuserectae and Pseudomonas viridiflava and the latter consists of Pseudomonas savastanoi and Pseudomonas syringae. The ‘Pseudomonas fluorescens complex’ is divided into two subpopulations, the ‘Pseudomonas fluorescens lineage’ and the ‘Pseudomonas chlororaphis lineage’. The ‘Pseudomonas fluorescens lineage’ contains Pseudomonas fluorescens biotypes A, B and C, Pseudomonas azotoformans, Pseudomonas marginalis pathovars, Pseudomonas mucidolens, Pseudomonas synxantha and Pseudomonas tolaasii, while the ‘Pseudomonas chlororaphis lineage’ includes Pseudomonas chlororaphis, Pseudomonas agarici, Pseudomonas asplenii and Pseudomonas corrugata. The ‘Pseudomonas putida complex’ comprises of Pseudomonas putida and Pseudomonas fulva.[10]

Clinical manifestations[change | change source]

More than 25 species of Pseudomonas cause diseases in humans. Species such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Pseudomonas fluorescens, Pseudomonas putida, Pseudomonas cepacia, Pseudomonas stutzeri, Pseudomonas maltophilia, and Pseudomonas putrefaciens are said to cause opportunistic infections in humans. [11] Opportunistic infections more commonly affect people with weak immune systems compared to the ones with stronger immune system.[12] Only two of the species are known to cause specific disease. These are Pseudomonas mallei and Pseudomonas pseudomallei which cause glanders and melioidosis respectively. However, the most common species involved in clinical problems is Pseudomonas aeruginosa.[13] The common clinical problems caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa is shown in the following bullet points.[14]

- Bone and joint infections (BJI): It has been noted that Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections are the most difficult to treat compared to other BJIs.[15]

- Cardiovascular (CV) infections

- Pseudomonal infectious endocarditis (IE)[16]

- Constrictive Pericarditis[17]

- Central Nervous System (CNS) infections

- Brain Abscess[18]

- Community-acquired Pseudomonas aeruginosa meningitis: It commonly occurs after surgery.[19]

- Ear infections[14]

- Otitis media and Otitis externa

- Chronic suppurative otitis media

- Eye infections

- Gastro-intestinal(GI) infections

- Genitourinary(GU) infections

- Epididymitis[27]

- Urinary tract infections (UTIs):[28] Pseudomonas aeruginosa is the common cause of nosocomial UTIs.[27] It is difficult to distinguish from other bacterial UTIs.[14]

- Respiratory infections

- Cystic fibrosis (CF)[29]

- Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP)[30]

- Sepsis[31]

- Skin and soft tissue infections

- Ecthyma gangrenosum (EG): It is rare but has very high mortality rate[32] ranging from 38%-77%.[33]

- Dermatitis: It is a form of mild cutaneous infection.[34]

- Necrotizing fasciitis: It is rare with only 12 cases recorded so far.[35]

Biotechnology[change | change source]

Pseudomonas strains have been useful in the biotechnology field. The table below shows the Pseudomonas strains and their respective uses.

| Scientific name of the strains | Uses |

|---|---|

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Treatment of rice blast disease[36] |

| Pseudomonas syringae | Production of frozen foods[36] |

| Pseudomonas putida | Control black root rot disease of tobacco [36] and the production of biosynthetic chemicals and drugs [37] |

| Pseudomonas fluorescens | Used in the food and leather industries [36] |

| Pseudomonas oleovorans | Used in the production of polyesters[36] |

References[change | change source]

- ↑ Lalucat, Jorge; Gomila, Margarita; Mulet, Magdalena; Zaruma, Anderson; García-Valdés, Elena (2021). "Past, present and future of the boundaries of the Pseudomonas genus: Proposal of Stutzerimonas gen. nov". Syst Appl Microbiol. 45 (1): 126289. doi:10.1016/j.syapm.2021.126289. hdl:10261/311157. PMID 34920232. S2CID 244943909.

- ↑ Gomila, Margarita; Peña, Arantxa; Mulet, Magdalena; Lalucat, Jorge; García-Valdés, Elena (2015). "Phylogenomics and systematics in Pseudomonas". Frontiers in Microbiology. 6: 214. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2015.00214. ISSN 1664-302X. PMC 4447124. PMID 26074881.

- ↑ "Etymologia: Pseudomonas". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 18 (8): 1241. August 2012. doi:10.3201/eid1808.ET1808. S2CID 26621145.

- ↑ Rudra, Bashudev; Duncan, Louise; Shah, Ajit J.; Shah, Haroun N.; Gupta, Radhey S. (2022). "Phylogenomic and comparative genomic studies robustly demarcate two distinct clades of Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains: proposal to transfer the strains from an outlier clade to a novel species Pseudomonas paraeruginosa sp. nov". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 72 (11): 005542. doi:10.1099/ijsem.0.005542. PMID 36355412. S2CID 253445493. Retrieved 7 July 2023.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Gomila, M; Peña, A; Mulet, M; Lalucat, J; García-Valdés, E (2015). "Phylogenomics and systematics in Pseudomonas". Frontiers in Microbiology. 6: 214. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2015.00214. PMC 4447124. PMID 26074881.

- ↑ Stanier, RY; Palleroni, NJ; Doudoroff, M (May 1966). "The aerobic pseudomonads: a taxonomic study". Journal of General Microbiology. 43 (2): 159–271. doi:10.1099/00221287-43-2-159. PMID 5963505.

- ↑ Saati-Santamaría, Z; Peral-Aranega, E; Velázquez, E; Rivas, R; García-Fraile, P (16 August 2021). "Phylogenomic Analyses of the Genus Pseudomonas Lead to the Rearrangement of Several Species and the Definition of New Genera". Biology. 10 (8): 782. doi:10.3390/biology10080782. PMC 8389581. PMID 34440014.

- ↑ Mulet, Magdalena; Gomila, Margarita; Scotta, Claudia; Sánchez, David; Lalucat, Jorge; García-Valdés, Elena (1 October 2012). "Concordance between whole-cell matrix-assisted laser-desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry and multilocus sequence analysis approaches in species discrimination within the genus Pseudomonas". Systematic and Applied Microbiology. 35 (7): 455–464. doi:10.1016/j.syapm.2012.08.007. PMID 23140936.

- ↑ Yamamoto, Satoshi; Kasai, Hiroaki; Arnold, Dawn L.; Jackson, Robert W.; Vivian, Alan; Harayama, Shigeaki (2000-10-01). "Phylogeny of the genus Pseudomonas: intrageneric structure reconstructed from the nucleotide sequences of gyrB and rpoD genes The GenBank accession numbers for the sequences determined in this work are: gyrB, D37926, D37297, D86005–D86019 and AB039381–AB039492; rpoD, D86020–D86036 and AB039493–AB039624". Microbiology. 146 (10): 2385–2394. doi:10.1099/00221287-146-10-2385. ISSN 1350-0872. PMID 11021915.

- ↑ Yamamoto, Satoshi; Kasai, Hiroaki; Arnold, Dawn L.; Jackson, Robert W.; Vivian, Alan; Harayama, Shigeaki (October 2000). "Phylogeny of the genus Pseudomonas: intrageneric structure reconstructed from the nucleotide sequences of gyrB and rpoD genes". Microbiology (Reading, England). 146 ( Pt 10): 2385–2394. doi:10.1099/00221287-146-10-2385. ISSN 1350-0872. PMID 11021915.

- ↑ Iglewski, Barbara H. (1996). "Pseudomonas". Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston. pp. Chapter 27. ISBN 978-0-9631172-1-2. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- ↑ "What is an Opportunistic Infection? | NIH". hivinfo.nih.gov. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- ↑ Iglewski, Barbara H. (1996). "Pseudomonas". Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston. pp. Chapter 27. ISBN 978-0-9631172-1-2. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 "Pseudomonas Infection Clinical Presentation: History, Physical, Causes". emedicine.medscape.com. Retrieved 2023-07-19.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Cerioli, Matteo; Batailler, Cécile; Conrad, Anne; Roux, Sandrine; Perpoint, Thomas; Becker, Agathe; Triffault-Fillit, Claire; Lustig, Sebastien; Fessy, Michel-Henri; Laurent, Frederic; Valour, Florent; Chidiac, Christian; Ferry, Tristan (2020-10-26). "Pseudomonas aeruginosa Implant-Associated Bone and Joint Infections: Experience in a Regional Reference Center in France". Frontiers in Medicine. 7: 513242. doi:10.3389/fmed.2020.513242. ISSN 2296-858X. PMC 7649271. PMID 33195289.

- ↑ Hassan, Kowthar S.; Al-Riyami, Dawood (2012-02-01). "Infective Endocarditis of the Aortic Valve caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Treated Medically in a Patient on Haemodialysis". Sultan Qaboos University Medical Journal. 12 (1): 120–123. doi:10.12816/0003099. ISSN 2075-051X. PMC 3286708. PMID 22375270.

- ↑ Chen, Jin-Ling; Mei, Dan-E; Yu, Cai-Gui; Zhao, Zhi-Yu (2022-07-26). "Pseudomonas aeruginosa-related effusive-constrictive pericarditis diagnosed with echocardiography: A case report". World Journal of Clinical Cases. 10 (21): 7577–7584. doi:10.12998/wjcc.v10.i21.7577. ISSN 2307-8960. PMC 9353922. PMID 36158001.

- ↑ Patel, Kevin; Clifford, David B. (2014-10-01). "Bacterial Brain Abscess". The Neurohospitalist. 4 (4): 196–204. doi:10.1177/1941874414540684. ISSN 1941-8744. PMC 4212419. PMID 25360205.

- ↑ Gallaher, Charles; Norman, James; Singh, Abhinav; Sanderson, Frances (2017-10-19). "Community-acquired Pseudomonas aeruginosa meningitis". BMJ Case Reports. 2017: bcr2017221839. doi:10.1136/bcr-2017-221839. ISSN 1757-790X. PMC 5665197. PMID 29054951.

- ↑ Lin, Jiaqi; Huang, Shanshan; Liu, Manli; Lin, Lixia; Gu, Jianjun; Duan, Fang (2022-09-14). "Endophthalmitis Caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Clinical Characteristics, Outcomes, and Antibiotics Sensitivities". Journal of Ophthalmology. 2022: 1265556. doi:10.1155/2022/1265556. ISSN 2090-004X. PMC 9492326. PMID 36157680.

- ↑ "Pseudomonas Keratitis - EyeWiki". eyewiki.aao.org. Retrieved 2023-07-20.

- ↑ Matejcek, Adela; Goldman, Ran D. (2013-11-01). "Treatment and prevention of ophthalmia neonatorum". Canadian Family Physician. 59 (11): 1187–1190. ISSN 0008-350X. PMC 3828094. PMID 24235191.

- ↑ Hoff, Ryan T.; Patel, Ami; Shapiro, Alan (2020-09-02). "Pseudomonas aeruginosa: An Uncommon Cause of Antibiotic-Associated Diarrhea in an Immunocompetent Ambulatory Adult". Case Reports in Gastrointestinal Medicine. 2020: 6261748. doi:10.1155/2020/6261748. ISSN 2090-6528. PMC 7484680. PMID 32934852.

- ↑ Coggins, Sarah A.; Wynn, James L.; Weitkamp, Jörn-Hendrik (2015-03-01). "Infectious Causes of Necrotizing Enterocolitis". Clinics in Perinatology. 42 (1): 133–154. doi:10.1016/j.clp.2014.10.012. ISSN 0095-5108. PMC 4328138. PMID 25678001.

- ↑ Qasim, Abdallah; Nahas, Joseph (2023), "Neutropenic Enterocolitis (Typhlitis)", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 31869058, retrieved 2023-07-22

- ↑ Colomba, Claudia; Scalisi, Michela; Ciacio, Valeria; Albano, Chiara; Bagarello, Sara; Billone, Sebastiano; Guida, Marco; Giordano, Salvatore; Canduscio, Laura A.; Milazzo, Mario; Amoroso, Salvatore; Cascio, Antonio (2022-11-01). "Shanghai Fever: Not Only an Asian Disease". Pathogens. 11 (11): 1306. doi:10.3390/pathogens11111306. ISSN 2076-0817. PMC 9699416. PMID 36365057.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Singhal, Sameer; Wagh, DD; Kashikar, Shivali; Lonkar, Yeshwant (2011-01-01). "A case of acute epididymo-orchitis due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa presenting as ARDS in an immunocompetent host". Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine. 1 (1): 83–84. doi:10.1016/S2221-1691(11)60075-0. ISSN 2221-1691. PMC 3609152. PMID 23569732.

- ↑ Mittal, Rahul; Aggarwal, Sudhir; Sharma, Saroj; Chhibber, Sanjay; Harjai, Kusum (2009-01-01). "Urinary tract infections caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa: A minireview". Journal of Infection and Public Health. 2 (3): 101–111. doi:10.1016/j.jiph.2009.08.003. ISSN 1876-0341. PMID 20701869.

- ↑ "Pseudomonas | Cystic Fibrosis Foundation". www.cff.org. Retrieved 2023-07-22.

- ↑ Ramírez-Estrada, Sergio; Borgatta, Bárbara; Rello, Jordi (2016-01-20). "Pseudomonas aeruginosa ventilator-associated pneumonia management". Infection and Drug Resistance. 9: 7–18. doi:10.2147/IDR.S50669. ISSN 1178-6973. PMC 4725638. PMID 26855594.

- ↑ Zakhour, Johnny; Sharara, Sima L.; Hindy, Joya-Rita; Haddad, Sara F.; Kanj, Souha S. (2022-10-18). "Antimicrobial Treatment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Severe Sepsis". Antibiotics. 11 (10): 1432. doi:10.3390/antibiotics11101432. ISSN 2079-6382. PMC 9598900. PMID 36290092.

- ↑ Biscaye, Stephanie; Demonchy, Diane; Afanetti, Mickael; Dupont, Audrey; Haas, Herve; Tran, Antoine (2017-01-13). "Ecthyma gangrenosum, a skin manifestation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa sepsis in a previously healthy child". Medicine. 96 (2): e5507. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000005507. ISSN 0025-7974. PMC 5266152. PMID 28079790.

- ↑ Martínez-Longoria, César Adrián; Rosales-Solis, Gloria María; Ocampo-Garza, Jorge; Guerrero-González, Guillermo Antonio; Ocampo-Candiani, Jorge (2017-09-10). "Ecthyma gangrenosum: a report of eight cases*". Anais Brasileiros de Dermatologia. 92 (5): 698–700. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20175580. ISSN 0365-0596. PMC 5674706. PMID 29166510.

- ↑ Greene, S. L.; Su, W. P.; Muller, S. A. (1984-01-01). "Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections of the skin". American Family Physician. 29 (1): 193–200. ISSN 0002-838X. PMID 6229990.

- ↑ Lota, A. S.; Altaf, F.; Shetty, R.; Courtney, S.; Mckenna, P.; Iyer, S. (2010-02-01). "A case of necrotising fasciitis caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa". The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery British Volume. 92-B (2): 284–285. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.92B2.22688. ISSN 2049-4408. PMID 20130324.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 36.3 36.4 Schaechter, Moselio (14 January 2009). Encyclopedia of microbiology (3rd ed.). Amsterdam Boston: Elsevier/Academic Press. ISBN 9780123739445.

- ↑ Weimer, A; Kohlstedt, M; Volke, DC; Nikel, PI; Wittmann, C (September 2020). "Industrial biotechnology of Pseudomonas putida: advances and prospects". Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 104 (18): 7745–7766. doi:10.1007/s00253-020-10811-9. PMC 7447670. PMID 32789744. S2CID 221111260.