Trojan asteroid

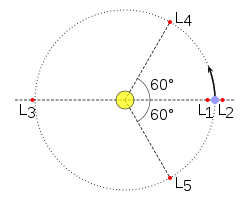

Trojan objects orbit 60° ahead (L4) or behind (L5) a more massive object. Both are in orbit around an even more massive central object. The best known example are the asteroids that orbit ahead or behind Jupiter around the Sun. Trojan objects do not orbit exactly at one of either Lagrange points, but do remain close to it, appearing to slowly orbit it.

The largest group of asteroids known to move around the Sun are those with the planet Jupiter. There are two groups of Jovian Trojans, one group on each side of Jupiter.

History[change | change source]

Theory[change | change source]

In 1772 the French mathematician and astronomer Joseph-Louis Lagrange identified two spots in a planet's orbit which were gravitationally stable. If put there, an object would stay there.[1] Lagrange predicted the existence of a group of small bodies in each of the two stable points in Jupiter’s orbit.

The term originally referred to the Trojan asteroids orbiting around Jupiter's Lagrangian points, which are by convention named after figures from the Trojan War of Greek mythology. By convention, the asteroids orbiting Jupiter's L4 point are named after the heroes from the Greek side of the war, while those at L5 are from the Trojan side. The two exceptions, the Greek-themed 617 Patroclus and the Trojan-themed 624 Hektor, were actually assigned to the wrong sides.[2][3]

Discoveries[change | change source]

In 1904, Edward Emerson Barnard was the first person to see a Trojan asteroid. Barnard thought it was a moon of the planet Saturn. In February 1906 a German astronomer named Max Wolf saw a Trojan asteroid and named it 588 Achilles. Wolf was the first person to see a Trojan asteroid and know what it was. Since that time, more than 2000 Trojan asteroids have been seen. The biggest Trojan asteroid is named 624 Hektor. 624 Hektor is 370 km across. Astronomers think that Trojan asteroids are made of ice and dust.

Later, objects were found orbiting the Lagrangian points of Neptune, Mars, and Earth.[4] Asteroids at the Lagrangian points of planets other than Jupiter may be called Lagrangian asteroids.[5]

- 5261 Eureka, 1998 VF31, 1999 UJ7, and 2007 NS2 are Mars Trojans.[6]

- Eight Neptune Trojans[7] are known, but they may outnumber the Jupiter Trojans by an order of magnitude.[8][9]

- 2010 TK7 was confirmed as the first known Earth Trojan in 2011. It is located in the L4 Lagrangian point, which lies ahead of Earth.[10]

Earth's Trojan[change | change source]

Astronomers have found a Trojan asteroid not far from Earth, moving in the same orbit around the Sun. It sits in one of the 'Lagrange points', which are 60 degrees ahead of or behind the planets in their orbits. These are points of gravitational stability.

Called 2010 TK7, the rock is about 80 million km from Earth, and should come no closer than about 25 million km. The team says its orbit appears stable at least for the next 10,000 years.

An orbiting telescope sensitive to infrared light found 2010 TK7. Wise, the Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer launched in 2009, examined more than 500 Near-Earth objects (NEOs), 123 of which were new to science. Follow-up work on the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope confirmed the status of 2010 TK7.[11]

Related pages[change | change source]

References[change | change source]

- ↑ They are not actually stationary, but each moves in an orbit within its Lagrange area.

- ↑ Wright, Alison (August 1, 2011). "Planetary science: The Trojan is out there". Nature Physics. 7 (8): 592. Bibcode:2011NatPh...7..592W. doi:10.1038/nphys2061. Retrieved 2011-08-12.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ↑ Robutel P. & Souchay J. 2010. "An introduction to the dynamics of trojan asteroids", in Dvorak, Rudolf & Souchay, Jean Dynamics of small Solar System bodies and exoplanets. Lecture Notes in Physics 790, Springer. p197 ISBN 3642044573

- ↑ Connors, Martin; Wieger, Paul; Veillet, Christian (27 July 2011). "Earth's Trojan asteroid". Nature. 475 (7357): 481–483. Bibcode:2011Natur.475..481C. doi:10.1038/nature10233. PMID 21796207. S2CID 205225571. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑ Robert J. Whiteley and David J. Tholen, "A CCD Search for Lagrangian Asteroids of the Earth–Sun System", Icarus 136:1, November 1998:154–167

- ↑ "List of Martian Trojans". Retrieved 2010-10-27.

- ↑ "List of Neptune Trojans". Retrieved 2010-10-27.

- ↑ Chiang, E. I. & Lithwick, Y. Neptune Trojans as a Testbed for Planet Formation, The Astrophysical Journal, 628, pp. 520–532 Preprint

- ↑ David Powell (30 January 2007). "Neptune may have thousands of escorts". Space.com. Retrieved 2007-03-08.

- ↑ Choi, Charles Q. (27 July 2011). "First Asteroid companion of Earth discovered at last". Space.com. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑ Amos, Jonathan 2011 Trojan asteroid seen in Earth's orbit by Wise telescope. BBC Science News. [1]