User:Uh139208

Leiden University, History of the Modern Middle East, 2021-22

I am a student enrolled in the course above, whose assessment entails editing a Simple Wikipedia entry. I will be using the space below to draft this entry.

Initial years under Ottoman rule[change | change source]

In 1453, the Ottoman Turks under the command of Sultan Mehmed II conquered the Byzantine capital of Constantinople.[1] Constantinople (later renamed Istanbul) became the capital of the Islamic Ottoman empire for the remainder of its lifespan (1453-1922.)[1] Under the Ottoman Empire, there were three main non-Muslim communities: the Jewish community, the Greek Orthodox Church and the Armenian apostolic church.[2] Christianity is a firmly embedded central component of Armenian history and culture, which dates back to 301 C.E when Armenia became the first ever nation to implement Christianity as a state religion.[3] Under Ottoman Islamic rule, Sultans allowed the Christian Armenian communities to preserve their culture, customs, language and religiosity so long as they remained loyal to the Ottoman sultan and the state.[1][2] This governance of the non-Muslim community was achieved through the implementation of what has become known as the millet system.[1]

Millet System[change | change source]

The system the Ottoman Empire implemented regarding the governance of their non-Muslim communities within the empire was known as the millet system. The word ‘millet’ which translated means ‘nation’ or ‘people’, also was used by the Ottomans to describe these non-Muslim groups as corporate religious groups within the empire.[1] Ultimately, the millet system entailed having non-Muslim religious communities such as the Armenian community guaranteed the right to life, a property, and the freedom to practice their religious faith so long as they remained loyal to the Sultan and the state.[2] Armenians were afforded this basic limited amount of autonomy provided they payed double the amount of taxes compared to a regular Ottoman citizen at the time.[1] These taxes were collected by influential leaders within the Armenian community who were also expected to deal with whatever additional issues that were occurring within the community at the time (social and legal.)[1] The millet system also determined that Armenians would be forbidden from participation within the military.[1] Other limitations were also in place which mandated Armenians and other millets to wear certain clothing and/or identifiers such as a crucifix around their neck.[1]

Armenian millets were operating just 8 years after the fall of Constantinople in 1453 when Sultan Mehmed II appointed Hovakim, an Armenian bishop to act as a ruling figurehead for the Armenian community.[2] Hovakim known as Hovakim I was the first Armenian Patriarch of Constantinople within the Ottoman Empire. Hovakim I was based in the Ottoman Capital in Istanbul where he was entrusted with commanding over the Armenian people and ensuring the prevention of anti-Ottoman movements within his community.[2] While a variation of the millet system may have been in place since the 1460’s, it is widely argued that the appearance of the term ‘millet’ gained prominence after the Ottoman Empire began to face serious multifaceted challenges to its empire vis-a-vis its military defeats to the Holy League in 1697 and the emergence of a new foe in Russia.[2] Each millet system enjoyed increasing influence and power at this time, particularly the Greek Patriarch of Constantinople and the Greek Phanariots.[4] The Phanariots were elite Greek merchants that had a critical influence over internal political issues within the Ottoman Empire.[4] Their influence within the Ottoman Empire was drastically reduced however after the Greek Revolution, with the other religious millets particularly the Armenian millets greatly benefiting from this shift of influence.[4]

By the 19th Century, the Armenian community was divided into Christian Apostolic, Catholic and Protestant millets, meaning that there was no centralized hierarchical leadership structure.[1] The Ottomans dealt with this Armenian division by having Armenian patriarchs for each millet in Istanbul and Jerusalem.[1] The ottomans had from an early stage of their reign, identified the crucial role that religious clergymen had in not only the collection of taxation within its community, but also of influencing the communities feelings and sentiments.[2] The relationship between the Armenian clergy and the Ottoman empire that existed up until the middle of the 19th century is one that certainly can be described as cordial and one of mutual benefit. The Armenian clergy and a small merchant faction within its elite enjoyed influence and power, while the Ottoman empire was intrinsically pleased with maintaining their power while also benefiting from the use of the Armenian merchants.[4] While the vast majority of Armenians were poor peasants, a small minority of Armenians would establish themselves as the financial backbone of the Ottoman Empire itself.[1] The Armenian Amira group of bankers would establish themselves as the most influential merchant group of the Ottoman Empire, serving as bankers to the Ottoman central government while also controlling key positions within crucial sectors of industry. Jobs such as the director of Imperial Currency Mint, chief imperial architect, and the superintendent of large Gun-powder factories were all being filled by the Amira group.[1] When one realizes the extent to which both the Armenian clergy and the Armenian elite were benefiting from the implementation of this millet system (particularly during the 18th/19th Century) it is easy to theorize why Armenia seemingly had made no clear demands for liberation until the Tanzimat reformation.[4]

Tanzimat Reforms[change | change source]

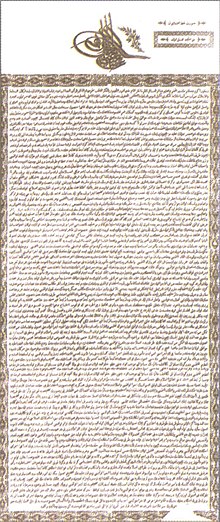

On November 3rd 1839, the process that became known as the Tanzimat reforms began when Sultan Abdulmecid's marked the opening of his reign with the issuance of the Hatt-ı Şerif of Gülhane.[5] The Hatt-ı Şerif of Gülhane was the brainchild of statesmen, Mustafa Reshid Pasha, the Ottoman minister of foreign affairs.[5] The Hatt-ı Şerif of Gülhane outlined three central notions in which: (i) The life, property and honor of all subjects under the Ottoman Empire must be guaranteed.(ii) A new fixed tax system would replace the outdated tax farming system and finally, (iii) Lifetime military conscription would be replaced to conscription of four to five years.[5] Perhaps the most notable and groundbreaking element of the Hatt-ı Şerif of Gülhane was its assertion that all Ottoman subjects regardless of religion would be equal before the law.[5] This is the first time during the Ottoman Empire in which non-Muslims would be deemed as equal to their muslim counterparts, something that would become a more regular occurence amongst the Sultan and Ottoman government during this period.[5]

On February 18th, 1856, thousands of citizens gathered in Istanbul to hear Sultan Abdulmecid’s Hatt-i Humayun, which was the second proclamation of the Tanzimat reforms.[5] While certain points were reiterated from the 1839 Hatt-ı Şerif of Gülhane proclamation, the 1856 Hatt-i Humayun was far more in-depth and specific.[5] For instance, this time there was specific reference to the need for adherence to annual national budgets, the creation of more banks and the adaptation of a more Europeanized economic model in hopes to build a stronger empire financially.[5] Similarly, steps would be taken that would lead to the introduction of commercial law and the codifying of penal law within the empire, while at the same time making penal reforms that would for example look to no longer punish apostates by death.[5] The proclamation greatly emphasized the fact that all citizens were now to be considered equal under Ottoman law regardless of religion. This intrinsically meant that the millet systems would have to be abandoned and all non-Muslim communities could naturally become citizens of the Ottoman Empire. Additionally, the sultan vowed that these historic minorities would be safeguarded and offered legal protection from discrimination with the final goal ultimately being to break down the barriers erected by the discriminatory millet system and create a brotherhood of Ottoman citizens that is both multi-ethnic and multi-national.[1][5]

The Land Code of 1858 was another feature of the Tanzimat reforms which revolutionized property and land ownership within the Ottoman Empire.[1] This Land Code entitled farmers, merchants and peasants who were living on land and/or farming on land to own properties which were previously under state ownership. The sultan agreed to sign away these properties he owned to these citizens of all classes who in turn would have to pay the sultan via newly established property taxation.[1] Ultimately, while the Tanzimat reforms were slow to be enacted, their seeming strides toward progression raised expectations particularly among those within the Armenian community.[6] More and more of the common Armenian population were educating themselves about reforms and laws within the community in which they previously had little to no say in.[6] Similarly, the elites within the Armenian population felt they had a part to play in helping to build a new reformed Ottoman Empire and generally were rather receptive of the Tanzimat reforms initially.[6] The construction of the first Constitution in 1876, during the First Constitutional Era was another seminal moment of reformation during the Tanzimat period, which would ultimately mark the end of this era. In the end, while the Tanzimat reforms seemed a success for the Ottoman Empire, the unchecked centralized nature of the sultan's power ultimately would lead to problems of drought and debt for the Ottoman Empire immediately following the end of the Tanzimat reforms.[1]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 Anderson, Betty S. (2016). A history of the modern Middle East : rulers, rebels, and rogues. Stanford, California. ISBN 978-0-8047-9875-4. OCLC 945376555.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Antaramian, Richard E. (2020). Brokers of faith, brokers of empire : Armenians and the politics of reform in the Ottoman Empire. Stanford, California. ISBN 978-1-5036-1296-9. OCLC 1124798032.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Cohan, Sara (2005). "A Brief History of the Armenian Genocide" (PDF). Social Education. 69 (6). ISSN 0037-7724.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Dimitrios, Ellis, S. G. Hálfdanarson, G. Isaacs, A. K. Pisa University Τμήμα Βαλκανικών Σλαβικών και Ανατολικών Σπουδών Σταματόπουλος, Δημήτριος Stamatopoulos, (2006). From Millets to Minorities in the 19th-Century Ottoman Empire: an Ambiguous Modernization. Pisa University Press, Edizioni Plus. OCLC 741821086.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 Davison, Roderic H. (1963). Reform in the Ottoman Empire, 1856-1876. Princeton, N.J. ISBN 978-1-4008-7876-5. OCLC 927442845.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Ueno, Masayuki (2013). ""FOR THE FATHERLAND AND THE STATE": ARMENIANS NEGOTIATE THE TANZIMAT REFORMS". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 45 (1): 93–109. doi:10.1017/s0020743812001274. ISSN 0020-7438.