Appendix (anatomy)

| Appendix | |

|---|---|

Drawing of colon with variability of appendix as seen from front | |

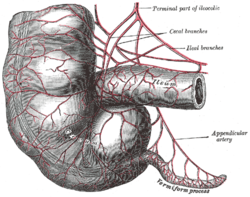

Arteries of cecum and appendix (appendix labeled as vermiform process at lower right) | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Midgut |

| System | Digestive system |

| Artery | Appendicular artery |

| Vein | Appendicular vein |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Appendix vermiformis |

| MeSH | D001065 |

| TA | A05.7.02.007 |

| FMA | 14542 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

In human anatomy, the appendix (or vermiform appendix; also cecal [or caecal] appendix; vermix; or vermiform process) is a blind ended tube connected to the cecum (or caecum).

The caecum is a pouch-like part of the colon. The appendix is near the junction of the small intestine and the large intestine. The term "vermiform" comes from Latin and means "worm-like in appearance". Its length is approximately 4 to 6 centimetres.

The appendix has no apparent function in the human body, but it can get inflamed and cause diseases (like appendicitis). In humans, it is a vestigial organ. It is assumed the appendix may act as a storage for beneficial ("good") gut bacteria which aid us on digesting difficult food and fighting germs.

Darwin suggested that the appendix was perhaps used to digest leaves as primates.[1] Over time, humans have eaten fewer vegetables and have evolved. Over thousands of years, this organ has become smaller to make room for the stomach. It is a vestigial organ which has degraded to nearly nothing in the course of evolution.

Herbivorous mammals such as the Koala have large appendices, and usually other adaptations as well. Cellulose, from plant cell walls, is hard to break down. The cecum of the koala is attached to the juncture of the small and large intestines as it is in humans, but is very long. This enables it to host bacteria specific for cellulose breakdown.

Early man’s ancestor may have also relied upon this system and lived on a diet rich in foliage. As man began to eat foods easier to digest, they became less reliant on cellulose-rich plants for energy.[1][2]

Reservoir of gut flora

[change | change source]Recent work shows the appendix is a safe place for useful bacteria when illness flushes those bacteria from the rest of the intestines.[3][4] This proposal is based on a new understanding of how the immune system supports the growth of beneficial gut flora,[5][6] in combination with many well-known features of the appendix, including its architecture, its location just below the normal one-way flow of food and germs in the large intestine, and its association with copious amounts of immune tissue. Research performed at Winthrop University-Hospital showed that individuals without an appendix were four times more likely to have a recurrence of Clostridium difficile colitis.[7] The appendix, therefore, may act as a "safe house" for commensal ("good") bacteria. This reservoir of gut flora could then serve to repopulate the digestive system following a bout of dysentery or cholera.[8]

References

[change | change source]- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Darwin, Charles 1871. The Descent of Man, and selection in relation to sex. John Murray: London.

- ↑ "The old curiosity shop". New Scientist. 2008-05-17.

- ↑ Associated Press. "Scientists may have found appendix's purpose". MSNBC, 5 October 2007. Accessed 17 March 2009.

- ↑ Bollinger R.R. et al 2007 (2007). "Biofilms in the large bowel suggest an apparent function of the human vermiform appendix". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 249 (4): 826–831. doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2007.08.032. ISSN 0022-5193. PMID 17936308.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Sonnenburg J.L; Angenent L.T. & Gordon J.I. 2004 (2004). "Getting a grip on things: how do communities of bacterial symbionts become established in our intestine?". Nat. Immunol. 5 (6): 569–73. doi:10.1038/ni1079. PMID 15164016. S2CID 25672527.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Everett M.L. et al 2004 (2004). "Immune exclusion and immune inclusion: a new model of host-bacterial interactions in the gut". Clinical and Applied Immunology Reviews. 4 (5): 321–32. doi:10.1016/j.cair.2004.03.001.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Dunn, Rob. "Your Appendix Could Save Your Life". Scientific American Blog Network.

- ↑ MBD July 22, 2013. Scientists finally discover the function of the human appendix. [1] Archived 2016-09-16 at the Wayback Machine