Battle of Aachen

| Battle of Aachen | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of World War II | |||||||

GI M1919 machine gun crew in action against German defenders in the streets of Aachen on 15 October 1944 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 100,000 soldiers |

13,000 soldiers 5,000 Volkssturm | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 5,000 casualties[1] |

5,000 casualties 5,600 prisoners[1] | ||||||

The Battle of Aachen was a major battle of Second World War. It was fought by American and German forces in and around Aachen, Germany, between 2–21 October 1944. The city was part of the Siegfried Line, the main defence line on Germany's western border. The Allies had hoped to capture it quickly and move into the Ruhr area.

Most of Aachen's civilian population was moved out before the battle began. Much of the city was destroyed and both sides had heavy losses. It was one of the largest urban battles fought by U.S. forces in World War II.

It was the first city in Germany to be captured by the Allies. The battle ended with a German surrender, but their defense slowed down Allied plans to advance into Germany.[2]

Background[change | change source]

By September 1944 the Western Allies had reached Germany's western border.[3] It was protected by the Siegfried Line.[4] On 17 September, British, American, and Polish forces launched Operation Market Garden.[5]

This was an attempt to get around the Siegfried Line by crossing the Lower Rhine River in the Netherlands.[6] The failure of this plan,[7] and a supply problem caused by the long distances,[8] stopped the Allied movement toward Berlin.[9]

German dead and wounded in France had been high. Field Marshal Walter Model said his 74 divisions had the strength of just 25.[10] The Western Allies' supply problems gave the Germans time to rebuild their strength.[11] In September, new troops were sent to the Siegfried Line. The total was 230,000 soldiers, including 100,000 new soldiers.[12]

At the start of the month the Germans had had about 100 tanks in the West;[13] by the end they had 500.[11] As men and equipment were moved into the Siegfried Line they were able to establish a depth of 4.8 kilometers (3.0 mi).[14]

The Allied force, under the command of General Dwight D. Eisenhower, wanted to capture the Ruhr. It was Germany's main industrial area.[15]

General George S. Patton's Third Army was ordered to occupy the French region of Lorraine.[16][17] General Courtney Hodges's First Army was ordered to attack near Aachen.[18]

Hodges had at first hoped to go around the city. He thought it was only defended by a small group of troops which would surrender once they were cut off.

The beautiful, old city Aachen was not an important military target, as it did not do much war production. Its population of around 165,000 had not been bombed by the Allies.[19]

It was an important symbol to the Nazi regime and the German people. It was the first German city threatened by an enemy during the Second World War. It was also the historic capital of Charlemagne, founder of the "First Reich".[20] The city was very important to the Germans.[21]

The city's defenders fought on home ground for the first time; one German officer said, "Suddenly we were no longer the Nazis, we were German soldiers."[22]

Aachen was protected by the Siegfried Line, a system of pillboxes, forts, and bunkers protected by anti-tank obstacles and barbed wire.[23] In several areas, German defenses were over 10 miles (16 km) deep.[24] It was the strongest defence ever built.[25]

Learning from their experiences on the Eastern Front, the Germans put their defences in the center of towns. They used narrow streets to make it hard for enemy armored vehicles to move around .[26]

Even though the troops defending Aachen and the Ruhr were of low quality, the fortifications protecting Aachen and the Ruhr were a major problem for the American forces.[27] Getting through Aachen was seen as important, because the land beyond Aachen was flat, and easy for the motorized Allied armies to travel on.[28]

Fighting around Aachen began in the second week of September.[29] The city was defended by the 116th Panzer Division, under the command of General Gerhard von Schwerin.[30]

The closeness of Allied forces had caused the majority of the city's government officials to leave before the citizens were moved out.[31] (For this, Hitler had all Nazi officials who had fled sent to the Eastern front as privates.)[32] von Schwerin wanted to surrender the city to Allied forces.[33] However, on 13 September, before he could surrender, he was ordered to launch a counterattack against American forces southwest of Aachen. He attacked with his panzergrenadier forces.[34]

The German general's attempt to surrender the city made Adolf Hitler, ordered the general's arrest. He was replaced by General Gerhard Wilck.[35] The United States' VII Corps continued to try to get past German defenses, despite the fighting on 12–13 September.[36]

Between 14–16 September the US 1st Infantry Division advanced against strong defenses and attacks. Eventually, they had a circle around half the city.[37]

This slow advance stopped in late September, due to the supply problem, and the sending of fuel and ammunition for Operation Market Garden in the Netherlands.[38]

Comparison of forces[change | change source]

German defenders in Aachen[change | change source]

In October, Aachen's defense was assigned to General Friedrich Köchling's LXXXI Corps. These forces, along with the attached 506th Tank Battalion and 108th Tank Brigade, had 20,000 men and 11 tanks.[39] Köchling was also promised a new 116th Panzer Division and the 3rd Panzergrenadier Division, with 24,000 troops.[40]

The 183rd Volksgrenadier Division and 49th Infantry Division defended the northern approaches. The 12th Infantry Division was positioned to the south.[41]

On 7 October, the 1st SS Panzer Division Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler Panzer Division were sent to defend Aachen.[42]

Although new troops continued to arrive, the 12th Infantry Division had lost half its combat strength between 16–23 September, and the 49th and 275th Infantry Divisions had had to be given time to rest.[43]

While German infantry divisions had a strength of 15,000–17,000 soldiers at the start of World War II, this had been reduced to a size of 12,500. By November 1944, the average strength of a division was 8,761 men.[44][45]

To cope with the troop shortages, the Volksgrenadier divisions were created in 1944. Their average total strength was just over 10,000 men per division.[46] Although about a quarter of these were experienced veterans, two-quarters were new soldiers and sick people while the rest were from the Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine.[47]

These divisions often received the newest small-arms, but they lacked artillery and motorization.[48] The 183rd Volksgrenadier Division had not had time to train as a unit.[49] The 246th Volksgrenadier Division was in a similar situation. Many of its troops had fewer than ten days of infantry training.[50][51] All of these weaknesses of the troops were made up for by the strong fortifications surrounding Aachen.[52]

American forces[change | change source]

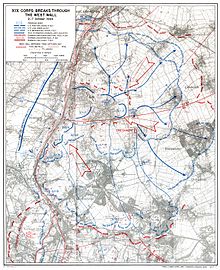

The task of capturing Aachen was given to General Charles H. Corlett's XIX Corps' 30th Infantry Division and Joseph Collins' VII Corps' 1st Infantry Division.[53]

General Leland Hobbs' 30th Infantry Division would be assisted by the 2nd Armored Division, which would try to go the 30th Division's hole in the Siegfried Line. Their sides were protected by the 29th Infantry Division.[54]

In the south, 1st Infantry Division was supported by the 9th Infantry Division and the 3rd Armored Division.[55] These divisions took in a large number of new men.[56]

By 1 October over 70% of the men of General Clarence Huebner's 1st Infantry Division were new troops. The last two weeks of September were spent giving these men training in fighting and weapons training.[57]

The plan called for both infantry divisions to avoid street fighting in Aachen. The plan was for the two divisions to encircle the city. Then a small force would capture it while most of the US forces moved east.[19]

Although American units were usually able to get new troops quickly, the replacements rarely had enough training. Many junior officers were lacked tactical and leadership abilities.[58] Some tank drivers had never even driven a car before. Some tank commanders had to teach their men how to load and fire their tank guns in the field before missions.[59]

The US system meant that new troops reaching the front lines were not properly trained for combat.[60] Sometimes half of a unit's replacements would become dead or wounded within the first few days of combat.[61]

These losses required more troops to be brought into the fighting. A battalion of the US 28th Infantry Division was sent against Aachen to help the US 1st Infantry Division during 18–21 October.[62]

These forces were supported by the Ninth Air Force, which knew where 75% of the pillboxes were. They planned an opening bombing using 360 bombers and 72 fighters. New aircraft would be used for a second attack, which included napalm.[63]

With the Germans having few anti-aircraft guns and severely limited support from the Luftwaffe, Allied forces controlled the skies over Aachen.[64]

Battle[change | change source]

For six days before the American attack allied artillery bombed German defenses around Aachen.[65] Although bombing German LXXXI Corps to stop all movements of troops and supplies, it did not harm the pillboxes and strongpoints.[64]

The opening air bombing on 2 October also did little damage to German defences. The 450 aircraft did not hit any German pillbox.[66] Their targets had been hidden by thick smoke from the Allied artillery.[67] After the aircraft finished their bombing, the artillery fired 18,696 shells.[68]

Advance from the north: 2–8 October[change | change source]

The 30th Infantry Division moved forward on 2 October. They used artillery to destroy German pillboxes. It took thirty minutes to capture a pillbox.[69] Heavy fighting had not been expected, and one group lost 87 troops in an hour;[70] another lost 93 out of 120 soldiers to a German artillery strike.[71]

The attackers were slowly able to cross the Wurm River. They attacked German pillboxes with flamethrowers and explosives.[72] By the afternoon of 2 October, the 30th Infantry Division had got past German defenses and reached the town of Palenberg.[73]

Here, US soldiers had to fight to get to each house.[74] (Private Harold G. Kiner was awarded the Medal of Honor for throwing himself on a German grenade saving the lives of two soldiers).[75]

Fighting in the town of Rimburg was terrible. American armour could not cross the Wurm River, and it could not support infantrymen who were attacking the Germans.[76] The 30th Infantry Division destroyed 50 German pillboxes on the first day.[77]

The division's advance was helped by the 29th Infantry Division's attacks. The Germans thought that the 29th Division's attacks were the main attack.[78]

On the night of 2 October, the German 902nd Assault Gun Battalion was ordered to attack the 30th Infantry Division. Allied artillery made the German attack not start on time. The German attack failed.[79]

American armor could help with the advance on 3 October. The US attacks were stopped by German attacks.[79] Rimburg was captured on the second day. Fighting had also begun in the town of Übach. American tanks tried to attack the town. However, they could not move due to German artillery fire.

American artillery fire stopped the Germans from recapturing it.[80] By the end of the day the 30th Infantry Division had around 300 dead and wounded.[81]

German forces continued their attacks on Übach. This stopped American troops from advancing.[82] On 4 October the Allies had only captured Hoverdor and Beggendorf. The Americans lost 1,800 soldiers in the past three days.[83] On 5 October, the 119th Regiment of the 30th Infantry Division captured Merkstein-Herbach.[84]

The next day the Germans attacked Übach, but the attack was not a success.[85] The American had many more tanks.[86] The Germans did not have extra troops.[87] General Koechling did get a Tiger tank group to defend Aachen from the north.[88]

The Germans attacked on 8 October with an infantry regiment, the 1st Assault Battalion, the 108th Panzer Brigade, and 40 armored vehicles.[89] The left side of the attack cut off an American platoon.[90][91] The Germans had many losses and the Americans were getting closer.

Advance from the south: 8–11 October[change | change source]

In the south, the 1st Infantry Division attacked on 8 October. They wanted to capture the town of Verlautenheide.[92] A big artillery attack helped them to capture the town.[93][94]

By 10 October, the 1st Infantry Division was in its planned position, where it could join with the 30th Infantry Division.[95] The Germans attacked but they ended up with over 40 dead and 35 prisoners.[96] Despite repeated German attacks, the 1st Infantry Division was able to capture the high land around the city.[97]

On 10 October, the US threatened to bomb the city if it didn't surrender.[98] The German commander refused to surrender.[99] American artillery fired 5,000 shells and the city was bombed American aircraft.[100]

Link up: 11–16 October[change | change source]

American dead and wounded were increasing. This was caused by German attacks and the danger of attacking pillboxes.[101] The Germans in the town of Bardenberg made pillboxes to defend themselves. American attackers pulled back and shelled the town with artillery.[102]

On 12 October, the Germans attacked the American 30th Infantry Division.[103] The Americans defended themselves with artillery fire and anti-tank defenses.[104]

At the village of Birk, there was a fight between German tanks and a single American Sherman tank. Then the 2nd Armored Division arrived and the Germans were pushed out of the town.[105]

The 30th Infantry Division had to defend itself over all the land they held. They were ordered to move south to join with the 1st Infantry Division.[106] Two infantry battalions from the 29th were sent to join the 30th.[107]

The same day (12 October), two German infantry regiments attempted to recapture. Both regiments were almost completely destroyed.[108] Between 11–13 October Allied aircraft bombed Aachen.[109]

On 15 October, the Germans again attacked the 1st Infantry Division. Although a number of heavy tanks managed to break through American lines, most of German forces were destroyed by artillery and airplanes.[110]

On the next day, the Germans attacked with the 3rd Panzergrenadier Division. They had heavy losses and they had to stop the attack.[111]

The 30th Infantry Division and parts of the 29th Infantry and 2nd Armored divisions moved southwards between 13–16 October. They could not get through German defenses and join up with allied forces to the south.[112]

The Germans attacked with artillery. German tanks were hidden in houses.[113] General Hobbs, commander of the 30th Infantry Division, tried to get around the German defenses. He attacked with two infantry battalions.[114] The attack was a success. The 30th and 1st Infantry Divisions joined up on 16 October.[115]

The fighting had caused American XIX Corps over 400 dead and 2,000 wounded, with 72% from the 30th Infantry Division.[116] The Germans had 630 of their soldiers killed and 4,400 wounded;[117] another 600 were killed in the 3rd Panzergrenadier Division's attack on the US 1st Infantry Division on 16 October.[118]

Fight for the city: 13–21 October[change | change source]

The 1st Infantry Division had only a single regiment to capture the city.[119] They attacked with machine guns and flamethrowers. Only by a few tanks and one howitzer were used in the attack.[120]

The city was defended by 5,000 German troops, including navy, air force and city police.[121] Most of these soldiers lacked experience and training. They were supported by a few tanks and assault guns.[122] However, Aachen's defenders could use the narrow streets to defend the city.[116]

The 26th Infantry's attack on 13 October was stopped by Germans firing from sewers and cellars. Sherman tanks could not move around in the narrow streets.[123][124] The 26th Infantry Regiment used howitzers to destroy German fortifications.[125][126] Sherman tanks were attacked by German anti-tank guns.[127]

American tanks and other armored vehicles would shoot buildings to kill any defenders hiding inside.[128] German infantry moved through sewers to attack Americans.[129]

The Germans fought very hard.[130] They attacked the Americans and used armor to stop American movement.[131]

On 18 October, the 3rd Battalion of the 26th Infantry Regiment prepared to attack the Hotel Quellenhof. This was one of the last areas held by the Germans in the city.[132] American tanks and other guns fired at the hotel.[133] That night, 300 new soldiers of the 1st SS Battalion moved into the hotel. They stopped several attacks on the building.[134]

A violent German attack managed to get past American infantry companies outside of the hotel. The Germans were then stopped by American mortar fire.[135]

The Americans shelled German positions with 155-millimeter (6.1 in) guns.[136] As well, a battalion of the 110th Infantry Regiment was used to fill gaps in the city. The new battalion was told on 19–20 October to attack the city.

On 21 October, soldiers of the 26th Infantry Regiment captured central Aachen.[137] The Germans in the Hotel Quellenhof surrendered, ending the battle for the city.[138]

References[change | change source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Ambrose (1997), p. 151

- ↑ Video: Allies Set For Offensive. Universal Newsreel. 1944. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ↑ Ambrose (1997), p. 117

- ↑ Ambrose (1997), p. 132

- ↑ Ambrose (1998), p. 238

- ↑ Ambrose (1997), p. 118–119

- ↑ Ambrose (1998), p. 247

- ↑ Mansoor (1999), p. 178

- ↑ (1999), p. 179

- ↑ Cooper (1978), p. 513

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 McCarthy & Syron (2002), pp. 219–220

- ↑ Yeide (2005), p. 55

- ↑ Yeide (2005), p. 25

- ↑ Yeide (2005), pp. 25–26

- ↑ Whitlock (2008), p. 34

- ↑ Ambrose (1998), p. 249

- ↑ Ambrose (1997), p. 136

- ↑ Mansoor (1999), p. 181

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Ambrose (1997), p. 146

- ↑ Whitlock (2008), p. 36; Hitler considered Charlemagne's Holy Roman Empire to be the First Reich.

- ↑ Rule (2003), p. 59

- ↑ Ambrose (1998), pp. 146–147

- ↑ Whiting (1976), p. 28

- ↑ Whiting (1976), pp. 28–29

- ↑ Ambrose (1997), p. 144

- ↑ Ambrose (1997), pp. 144–145

- ↑ Combined Arms in Battle Since 1939, pp. 163–164

- ↑ Yeide (2005), p. 34

- ↑ Yeide (2005), p. 35

- ↑ Whiting (1976), pp. 33–34

- ↑ Whiting (1976), p. 35

- ↑ Ambrose (1998), p. 147

- ↑ Whiting (1976), pp. 35–37

- ↑ Whiting (1976), p. 43

- ↑ Whitlock (2008), p. 37

- ↑ Hitler's Army, pp. 313–314

- ↑ Hitler's Army, pp. 315–318

- ↑ Hitler's Army, pp. 318–319

- ↑ Whiting (1976), p. 80

- ↑ Whiting (1976), p. 81

- ↑ Ferrell (2000), pp. 31–32

- ↑ Ferrell (2000), p. 32, claims it was a panzer corps; Whiting (1976), pp. 114–115, clarifies that this was the 1st Panzer Battalion of the 1st SS Panzer Division.

- ↑ Hitler's Army, p. 320

- ↑ Hitler's Army, p. 33

- ↑ Fighting Power, p. 56

- ↑ Hitler's Army, pp. 33–34

- ↑ Hitler's Army, p. 34

- ↑ Hitler's Army, pp. 34–35

- ↑ Yeide (2005), p. 59

- ↑ Yeide (2005), pp. 59–60

- ↑ Yeide (2005), p. 60

- ↑ Mansoor (1999), p. 182

- ↑ Rule (2003), p. 60

- ↑ Hitler's Army p. 321

- ↑ Whitlock (2008), pp. 37–38

- ↑ Whiting (1976), pp. 76–77

- ↑ Ambrose (1997), p. 145

- ↑ Ambrose (1998), p. 260

- ↑ Ambrose (1998), p. 262

- ↑ Ambrose (1998), pp. 262–263

- ↑ Ambrose (1998), p. 264

- ↑ Stanton, Shelby, World War II Order of Battle: An Encyclopedic Reference to U.S. Army Ground Forces from Battalion through Division, 1939-1946, Stackpole Books (Revised Edition 2006), p. 105; other details of US unit commitments at Aachen can also be found on pp. 50, 51, and 76 of the same volume.

- ↑ Whiting (1976), p. 82

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 Hitler's Army, p. 323

- ↑ Ambrose (1997), p. 147

- ↑ Rule (2003), pp. 60–61

- ↑ Ambrose (1997), pp. 147–148

- ↑ Ambrose (1997), p. 148

- ↑ Ambrose (1997), pp. 148–149

- ↑ Hitler's Army, pp. 323–324

- ↑ Whiting (1976), p. 89

- ↑ Whiting (1976), pp. 89–90

- ↑ Whitlock (2008), p. 39

- ↑ Whiting (1976), p. 91

- ↑ Whitlock (2008), pp. 39–40

- ↑ Whiting (1976), pp. 91–92

- ↑ Rule (2003), pp. 61–62

- ↑ Rule (2003), p. 62

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 Hitler's Army, p. 324

- ↑ Whitlock (2008), p. 40

- ↑ Whiting (1976), p. 96

- ↑ Hitler's Army, p. 326

- ↑ Whiting (1976), p. 98

- ↑ Yeide (2005), p. 68

- ↑ Yeide (2005), p. 70

- ↑ Whiting (1976), pp. 190–191

- ↑ Whiting (1976), pp. 102–103

- ↑ Yeide (2005), p. 71

- ↑ Hitler's Army, p. 327

- ↑ Yeide (2005), pp. 71–72

- ↑ Yeide (2005), p. 72

- ↑ Whiting (1976), pp. 106–108

- ↑ Rule (2003), pp. 62–63

- ↑ Whitlock (2008), p. 41

- ↑ Ferrell (2000), p. 33

- ↑ Yeide (2005), p. 76

- ↑ Yeide (2005), pp. 76–77

- ↑ Whiting (1976), p. 110

- ↑ Whiting (1976), p. 111

- ↑ Whiting (1976), pp. 111-112

- ↑ Whiting (1976), pp. 113–114

- ↑ Hitler's Army, p. 329

- ↑ Yeide (2005), p. 80

- ↑ Yeide (2005), pp. 80–81

- ↑ Whiting (1976), pp. 115–116

- ↑ Whiting (1976), pp. 117–118

- ↑ Yeide (2005), p. 81

- ↑ Yeide (2005), pp. 81–82

- ↑ Yeide (2005), p. 82

- ↑ Hitler's Army, p. 331

- ↑ Hitler's Army, pp. 331–332

- ↑ Hitler's Army, p. 330

- ↑ Yeide (2005), p. 83

- ↑ Whiting (1976), pp. 122–123

- ↑ Yeide (2005), p. 87

- ↑ 116.0 116.1 Yeide (2005), p. 88

- ↑ Yeide (2005), p. 84

- ↑ Yeide (2005), pp. 87–88

- ↑ Combined Arms in Battle Since 1939, p. 164

- ↑ Whitlock (2008), p. 42

- ↑ Combined Arms in Battle Since 1939, pp. 164–166

- ↑ Rule (2003), p. 66

- ↑ Whiting (1976), pp. 137–139

- ↑ Combined Arms in Battle Since 1939, p. 167

- ↑ Rule (2003), pp. 66–67

- ↑ Whitlock (2008), pp. 42–43

- ↑ Whitlock (2008), p. 43

- ↑ Combined Arms in Battle Since 1939, pp. 167–168

- ↑ Yeide (2005), p. 93

- ↑ Yeide (2005), p. 92

- ↑ 'Combined Arms in Battle Since 1939, p. 168

- ↑ Whitlock (2008), p. 45

- ↑ Whiting (1976), p. 148

- ↑ Whiting (197), pp. 149–150

- ↑ Whiting (1976), pp. 151–154

- ↑ Whiting (1976), p. 176

- ↑ Stanton, Shelby, World War II Order of Battle: An Encyclopedic Reference to U.S. Army Ground Forces from Battalion through Division, 1939-1946, Stackpole Books (Revised Edition 2006), p. 105

- ↑ Combed Arms in Battle Since 1939, p. 169

Bibliography[change | change source]

- Spiller, Roger J., ed. (1991). Combined Arms in Battle Since 1939. U.S. Army Command and General Staff College Press. OCLC 25629732. Archived from the original on 2007-05-15. Retrieved 2014-11-18.

- the ed. of Command magazine (1995). Hitler's Army: The Evolution and Structure of German Forces, 1933–1945. Conshohocken, PA: Combined Books Inc. ISBN 0-938289-55-1.

- Ambrose, Stephen E. (1997). Citizen Soldiers: The U.S. Army From the Normandy Beaches to the Bulge to the Surrender of Germany. New York City, New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-81525-7.

- Ambrose, Stephen E. (1998). Victors. New York City, New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-85628-X.

- Cooper, Matthew (1978). The German Army 1933-1945. Lanham, Maryland: Scarborough House. ISBN 0-8128-8519-8.

- Bruce K. Ferrell (November 2000). "The Battle of Aachen" (PDF). Armor. Fort Knox, Kentucky: 30. ISSN 0004-2420. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-02-15. Retrieved 2022-05-03.

- Mansoor, Peter R. (1999). The GI Offensive in Europe: The Triumph of American Infantry Divisions, 1941–1945. Lawrence, Kansas: Kansas University Press. ISBN 0-7006-0958-X.

- McCarthy, Peter; Mike Syryon (2002). Panzerkieg: The Rise and Fall of Hitler's Tank Divisions. New York City, New York: Carroll & Graf. ISBN 0-7867-1009-8.

- Rule, Richard (April 2003). "Bloody Aachen". Military Heritage. 4 (5). Herndon, Virginia: Sovereign Media. ISSN 1524-8666.

- Stanton, Shelby (2006). World War II Order of Battle: An Encyclopedic Reference to U.S. Army Ground Forces from Battalion through Division, 1939-1946. Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-0157-0.

- Whiting, Charles (1976). Bloody Aachen. Briarcliff Manor, New York: Stein and Day.

- Whitlock, Flint (December 2008). "Breaking Down the Door". WWII History. 7 (7). Herndon, Virginia: Sovereign Media. ISSN 1539-5456.

- Yeide, Harry (2005). The Longest Battle: September 1944 to February 1945. St. Paul, MN: Zenith Press. ISBN 0-7603-2155-8.