Zhuyin

| Bopomofo | |||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 注音符號 | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 注音符号 | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

Zhuyin Fuhao, often shortened as zhuyin and commonly called bopomofo, is a type of sound-based writing for the Chinese language. In Chinese, "bo", "po", "mo" and "fo" are the first four of the conventional ordering of available syllables. As a result, the four syllables together have been used to refer to many different phonetic systems. For Chinese speakers who were first introduced to the Zhuyin system, "bopomofo" means zhuyin fuhao.

| Zhuyin | Pinyin | Origin |

|---|---|---|

| Initials | ||

| ㄅ | b | From 勹, the top portion 包, bāo |

| ㄆ | p | From 攵, the combining form of 攴, pū |

| ㄇ | m | From 冂, the archaic form of the radical 冖, mì |

| ㄈ | f | From 匚, fāng |

| ㄉ | d | From the archaic form of 刀, dāo. Compare the bamboo form. |

| ㄊ | t | From the upside-down 子 seen at the top of 充 |

| ㄋ | n | From 𠄎, ancient form of 乃, nǎi |

| ㄌ | l | Calligraphic form of 力, lì |

| ㄍ | g | From the obsolete character 巜, guì/kuài, 'river' |

| ㄎ | k | From 丂 from 考, kǎo |

| ㄏ | h | From 厂, hàn |

| ㄐ | j | From the archaic character 丩 from 纠, jiū |

| ㄑ | q | From the archaic character ㄑ, quǎn, graphic root of the character 巛, chuān (modern 川) |

| ㄒ | x | From 丅, a seal form of 下, xià. |

| ㄓ | zh | From |

| ㄔ | ch | From the radical 彳, chì |

| ㄕ | sh | From the character 尸, shī |

| ㄖ | r | A semi-cursive form of 日, rì |

| ㄗ | z | From the radical 卩 节, jié, dialectically zié |

| ㄘ | c | Variant of 七, qī, dialectically ciī. Compare semi-cursive form and seal-script. |

| ㄙ | s | From the old character 厶, sī, which was later replaced by its compound 私, sī. |

| Finals | ||

| ㄧ | i, y | From 一, yī |

| ㄨ | u, w | From 㐅, ancient form of 五, wǔ. |

| ㄩ | ü, yu | From the ancient character 凵, qū, which remains as a radical |

| ㄚ | a | From 丫, yā |

| ㄛ | o | From the obsolete character 𠀀 hē, inhalation, the reverse of 丂 考, kǎo, which is preserved as a phonetic in the compound 可, kě.[1] |

| ㄜ | e | Derived from its allophone in Standard Mandarin, ㄛ, o |

| ㄝ | e | From 也, yě. Compare the Warring States bamboo form. |

| ㄞ | ai | From 𠀅 hài, bronze form of 亥. |

| ㄟ | ei | From 乁 yí, an obsolete character meaning 移, yí, "to move". |

| ㄠ | ao | From 幺, yāo |

| ㄡ | ou | From 又, yòu |

| ㄢ | an | From the obsolete character ㄢ, hàn, "to bloom", preserved as a phonetic in the compound 犯, fàn |

| ㄣ | en | From 乚, yǐn |

| ㄤ | ang | From 尢, wāng |

| ㄥ | eng | From 厶, an obsolete form of 厷, gōng |

| ㄦ | er | From 儿, the bottom portion of 兒, ér used as a cursive form |

| ㄭ | i | ( |

The zhuyin characters are represented in typographic fonts as if drawn with an ink brush (as in Regular Script). They are encoded in Unicode in the bopomofo block, in the range U+3105 ... U+312D.

History

[change | change source]After the overthrow of China's last emperor during the Xinhai Revolution in 1911, the new government in China created Zhuyin to help the common people read more easily.[2] However, the Chinese Communist Party wanted to ban writing Chinese characters altogether and replace them with the Latin alphabet.[3] When the People's Liberation Army defeated the Kuomintang (the founding party of the Republic of China) in 1949 and sent them off to exile in Taiwan, the use of Zhuyin dropped in mainland China because the CPC was interested in using the Latin alphabet for writing Chinese phonetically.[2] However, Zhuyin is still widely used in Taiwan as it is used to type Chinese on computer and phone keyboards.

Features

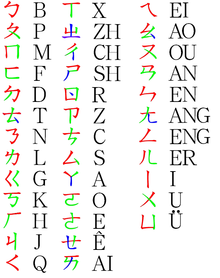

[change | change source]Zhuyin was made to closely represent the sounds of Mandarin Chinese. Symbols are divided into two categories, the initials (the first sounds in a syllable) and the finals (the main vowel, the glide consonants ([y/i; IPA:/j/] and [w/u; IPA:/w/]) that come before the main vowel and all the sound that comes after it). There are 4 tone marks to represent the 5 Mandarin tones.

References

[change | change source]- ↑ "Unihan data for U+ 20000".

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Zhuyin fuhao / Bopomofo". omniglot.com. Retrieved 2017-07-09.

- ↑ "Oracle Bones". The New Yorker. Retrieved 2017-07-09.