Emperor penguin

| Emperor penguin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Adults with a chick on Snow Hill Island, Antarctic Peninsula | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Sphenisciformes |

| Family: | Spheniscidae |

| Genus: | Aptenodytes |

| Species: | A. forsteri

|

| Binomial name | |

| Aptenodytes forsteri Gray, 1844

| |

| |

| Emperor penguin range (breeding colonies in green) | |

The Emperor penguin (Aptenodytes forsteri) is a penguin that lives in Antarctica. It is the tallest and heaviest penguin. They are the only birds that can lay their eggs on ice.[2]

Emperors are the biggest of the 18 species of penguin found today, and one of the largest of all birds. Emperor penguins are about 1.1 m (4 ft) tall, weigh up to 45 kg (99 lb) and have a wingspan of 30 in (76 cm).[2] Emperor Penguins are black and white like all penguins, and the sides of their neck and chest are golden. They can dive deeper than any other bird, including other penguins. Emperor penguins are also the largest penguins in the world. Emperors are the biggest of the 18 species of penguin found today and one of the largest of all birds. There are approximately 595,000 adult Emperor penguins in Antarctica. Emperor penguins do not build nests they lay their eggs on the ice through their legs. Like other penguins, emperors leap into the air while swimming, which is called porpoising.

Life[change | change source]

They eat mostly crustaceans, such as krill, and fish but also eat cephalopods, such as squid, cuttlefish, and octopuses.

Emperors live in the coldest climate on earth. Temperatures can drop as low as -140 degrees Fahrenheit (-95.6 °C) on the Antarctic ice. They breed at the beginning of the Antarctic winter (March and April), on the ice all around the Antarctic continent. They live in large groups, called colonies, that can have up to 20,000 birds.[3] They huddle close together to keep warm.[3] Emperor penguins live for about 20 years, although some have been known to live for 40 years.[4] They dive at their food and they stay in small groups

The shape of their body helps them to survive. They have short wings that help them swim and to dive up to 900 ft (274 m) to catch larger fish. The deepest dive recorded is 525 m (1,722 ft).[3] They can swim up to 15 km/h (9 mph) for a short time,[2] which lets them escape their main enemy, the leopard seal. They can stay warm because they have a thick layer of blubber. The layer of downy feathers trap air that keeps the body heat in and cold air and water out. They also have large amounts of body oil that help in keeping them dry in the water.

While they are very fast in the water, on land the birds can only walk very slowly. On ice they can lie on their stomachs and use their wings to slide along, like a sled.[2]

Breeding[change | change source]

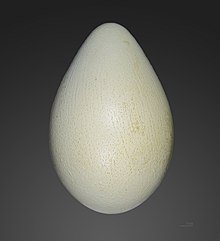

Emperor penguins spend most of their time in the water, coming to the shore to breed.[2] There is nothing on the ice to make a nest, so after the female lays her one egg in winter, the male puts the egg on his feet to keep it warm until spring.[2] This can be from 65 to 75 days.[5] He has a special fold of skin on his stomach which can fold over and cover the egg to keep it warm.[6] This is a difficult action to swap the egg from the female to the male; if it sits for too long on the ice it will freeze.[4] He does not eat during this time, and can lose up to half his weight.[2] To keep warm, all the male penguins huddle together. Those on the outside of the group will slowly shuffle their way into the middle; the group is always moving and can move as much as 200 m (219 yd) in 24 hours.[6] The female comes back in spring when the egg hatches, while the male will go back to sea to eat, but comes back to help look after the chick.[2] The chick lives on its parents feet for about 50 days until it becomes strong enough to survive the cold.[3]

Movies[change | change source]

The Australian movie Happy Feet was based on the story of an emperor penguin who is unable to sing and get a mate because he was left for too long on the ice when still an egg.

The documentary March of the Penguins is about emperor penguins moving across the ice to lay eggs.

Other websites[change | change source]

References[change | change source]

- ↑ BirdLife International (2012). "Aptenodytes forsteri". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 Discovering wildlife – the ultimate fact file. International Masters Publishers BV MMV. 2002. p. 5.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 "Emperor penguins". Australian Antarctic Division. June 3, 2009. Archived from the original on 2009-10-30. Retrieved 2009-12-10.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Wienecke, Barbara. "The Emperor Penguin: Aptenodytes forsteri". Emperor Penguin .com. Retrieved 2009-12-10.

- ↑ "Breeding cycle". Emperor penguins. Austalian Antarctic Division. Archived from the original on 2009-09-29. Retrieved 2009-12-13.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Emperor Penguins: winter survivors". Australian Antarctic Division. Retrieved 2009-12-12.