The Tell-Tale Heart

| "The Tell-Tale Heart" | |

|---|---|

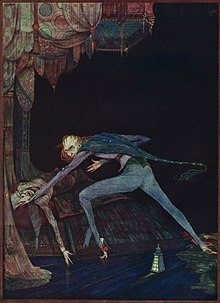

Illustration by Harry Clarke, 1919 | |

| Author | Edgar Allan Poe |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre(s) | Horror |

| Published in | The Pioneer |

| Publisher | James Russell Lowell |

| Media type | |

| Publication date | January 1843 |

"The Tell-Tale Heart" is an 1843 short story by Edgar Allan Poe. Detectives capture a man who admits to the killing of the old man with a strange eye. The murder is carefully planned, and the killer killed the old man by pulling his bed on top of the man and hiding the body under the floor. The killer feels guilty about the murder, and the guilt makes him imagine that he can hear the dead man's heart still beating under the floor.

No one knows if the old man and the killer are related. Some people think that the old man is a father figure. Some people think that the man is strange, perhaps that his vulture eye represents some sort of veiled secret.

The story was first published in James Russell Lowell's The Pioneer in January 1843. "The Tell-Tale Heart" is one of Poe's most famous short stories, and it is widely considered a classic of the Gothic fiction genre. The story has been made into or inspired many different works in film, television, and other media.

Story[change | change source]

"The Tell-Tale Heart" is a story told in the first-person. This means it is told from the perspective of the narrator. The story does not say if the narrator is male or female.

The narrator is living with an old man with a clouded, vulture-like eye. The narrator has feelings of paranoia, and becomes afraid of the old man's strange eye. The narrator becomes so bothered by the eye that they plot to murder the old man. For more than a week, the narrator sneaks into the old man's room at night, watching and waiting for the right time to strike. However, the old man's eyes are shut, hiding the clouded eye, and the narrator loses the urge to kill.

One night, though, the old man awakens as the narrator watches, revealing the eye. The narrator strikes, smothering the old man with his own mattress. The narrator chops up the body, and hides the pieces under the floorboards. The narrator then cleans the place up to hide all signs of the crime. When the narrator reports that the police (whether a delusion or real is unclear) respond to a call placed by a neighbor who heard a distressful scream, the narrator invites them to look around, confident that they will not find any evidence of the murder. They sit around the old man's room, right on top of the very hiding place of the dead body, yet suspect nothing.

The narrator, however, begins to hear a faint noise. As the noise grows louder, the narrator hallucinates that it is the heartbeat of the old man coming from under the floorboards. This paranoia increases as the officers seem to pay no attention to the sound, which is loud enough for the narrator to admit having heard. Shocked by the constant beating of the heart and a feeling that the officers must be aware of the heartbeats, the narrator loses control and confesses to killing the old man and tells them to tear up the floorboards to reveal the body.

Throughout the story the narrator insists on being sane, yet at the same time, giving the impression of serious hallucinations or paranoia, possibly caused by guilt from having murdered an elderly man.

Analysis[change | change source]

"The Tell-Tale Heart" starts in medias res, in the middle of an event. The opening is an in-progress conversation between the narrator and another person who is not identified in any way. It is speculated that the narrator is confessing to a prison warden, judge, newspaper reporter, doctor or psychiatrist.[1] Whoever it is, it sparks the narrator's need to explain himself in great detail.[2] The first word of the story, "True!," is an admission of his guilt.[1]

One of the driving forces in this opening and throughout the story is not the narrator's insistence upon his innocence but on his sanity. His drive to convince, however, is self-destructive because he fully admits he is guilty of murder.[3] His denial of insanity is based on his systemic actions and precision - a rational explanation for irrational behavior (murder).[2] This rationality, however, is undermined by his lack of motivation ("Object there was none. Passion there was none."). Despite this, however, he says the idea of murder, "haunted me day and night."[3] The story's final scene, however, is a result of the narrator's feelings of guilt. Like many characters in the Gothic tradition, his nerves dictate his true nature. Despite his best efforts at defending himself, the narrator's "over acuteness of the senses," which help him hear the heart beating in the floorboards, is what convinces the reader that he is truly mad.[4] Readers during Poe's time would have been especially interested amidst the controversy over the insanity defense in the 1840s.[5]

It is unclear, however, if the narrator actually has very acute senses or if he is merely imagining things. If his condition is believed to be true, what he hears at the end of the story may not be the old man's heart but death watch beetles. The narrator first admits hearing death watches in the wall after startling the old man from his sleep. According to superstition, death watches are a sign of impending death. One variety of death watch beetles raps its head against surfaces, presumably as part of a mating ritual, while others emit a ticking sound.[6]

The relationship between the old man and the narrator is ambiguous, as is their names, their occupations, or where they live. In fact, that ambiguity adds to the tale as an ironic counter to the strict attention to detail in the plot.[7] The narrator may be a servant of the old man's or, as is more often assumed, his son. In that case, the "vulture" eye of the old man is symbolizing parental surveillance and possibly the paternal principles of right and wrong. The murder of the eye, then, is a removal of conscience.[8] The eye may also represent secrecy, again playing on the ambiguous lack of detail about the man or the narrator. Only when the eye is finally found open on the final night, penetrating the veil of secrecy, that the murder is carried out.[9]

Former poet laureate Richard Wilbur has suggested that the tale is an allegorical representation of Poe's poem "To Science." The poem shows the struggle between imagination and science. In "The Tell-Tale Heart," the old man represents the scientific rational mind while the narrator is the imaginative.[10]

Publication history[change | change source]

"The Tell-Tale Heart" was first published in the Boston-based magazine The Pioneer in January 1843, edited by James Russell Lowell. Poe was likely paid only $10.[11] It was slightly revised when republished in the August 23, 1845 edition of the Broadway Journal. It was reprinted multiple times during Poe's lifetime.[12]

Adaptations[change | change source]

- As of 2007-09-01 the Internet Movie Database lists 21 adaptations.[13]

- An animated film version by UPA, read by James Mason, The Tell-Tale Heart (1953),[14] is included among the films preserved in the United States National Film Registry.

- The Tell-Tale Heart, 1960 version.[15]

- A reading of the story was performed by Winifred Phillips, with music composed by her, as part of the NPR "Tales by American Masters" series in 1998 and released on DH Audio.

- The Canadian radio program Nightfall presented an adaptation on August 1st, 1980.

Works inspired[change | change source]

Music

- "The Tell-Tale Heart" is one of several songs inspired by Poe stories on the album Tales of Mystery and Imagination (original version 1976, CD remix 1987) by The Alan Parsons Project. It is sung by Arthur Brown.

- In 2003, Lou Reed released his concept album The Raven comprised of several works inspired by Poe, including the track "The Tell-Tale Heart."

- In Insane Clown Posse's 1995 album The Riddlebox, the track "Ol' Evil Eye" was inspired by this story.

- The song "Ride the Wings of Pestilence" by California-based post-hardcore band From First to Last shows similarities to "The Tell-Tale Heart". However, this has never been confirmed.

Television

- An episode of The Simpsons ("Lisa's Rival," September 11, 1994) featured a "Tell-Tale Heart"-inspired act of revenge between Lisa and a new student. In the episode, Lisa hides the competing student's diorama of the story and replaces it with an actual animal heart. As her guilt rises, she thinks she hears the diorama's heart beating beneath the floor boards.

- A season 1 episode of SpongeBob SquarePants, "Squeaky Boots", has Mr. Krabs burying a pair of squeaky boots underneath the floorboards, only to begin hearing the noise more and more before snapping and digging them up, saying, "It is the squeaking of the hideous boots!"

References[change | change source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Benfey, Christopher. "Poe and the Unreadable: 'The Black Cat' and 'The Tell-Tale Heart'," collected in New Essays on Poe's Major Tales, Kenneth Silverman, ed. Cambridge University Press, 1993. ISBN 978-0-521-42243-7 p. 30

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Cleman, John. "Irresistible Impulses: Edgar Allan Poe and the Insanity Defense", collected in Bloom's BioCritiques: Edgar Allan Poe, edited by Harold Bloom. Philadelphia: Chelsea House Publishers, 2001. p. 70 ISBN 0-7910-6173-6

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Robinson, E. Arthur. "Poe's 'The Tell-Tale Heart'" from Twentieth Century Interpretations of Poe's Tales, edited by William L. Howarth. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall Inc., 1971. p. 94

- ↑ Fisher, Benjamin Franklin. "Poe and the Gothic Tradition," from The Cambridge Companion to Edgar Allan Poe, edited by Kevin J. Hayes. Cambridge University Press, 2002. p. 87 ISBN 0-521-79727-6

- ↑ Cleman, John. "Irresistible Impulses: Edgar Allan Poe and the Insanity Defense", collected in Bloom's BioCritiques: Edgar Allan Poe, edited by Harold Bloom. Philadelphia: Chelsea House Publishers, 2001. p. 66 ISBN 0-7910-6173-6

- ↑ Reilly, John E. "The Lesser Death-Watch and "'The Tell-Tale Heart'," collected in The American Transcendental Quarterly. Second quarter, 1969. Available online Archived 2009-12-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Benfey, Christopher. "Poe and the Unreadable: 'The Black Cat' and 'The Tell-Tale Heart'," collected in New Essays on Poe's Major Tales, Kenneth Silverman, ed. Cambridge University Press, 1993. ISBN 978-0-521-42243-7 p. 32

- ↑ Hoffman, Daniel. Poe Poe Poe Poe Poe Poe Poe. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1972. p. 223 ISBN 0-8071-2321-8

- ↑ Benfey, Christopher. "Poe and the Unreadable: 'The Black Cat' and 'The Tell-Tale Heart'," collected in New Essays on Poe's Major Tales, Kenneth Silverman, ed. Cambridge University Press, 1993. ISBN 978-0-521-42243-7 p. 33

- ↑ Benfey, Christopher. "Poe and the Unreadable: 'The Black Cat' and 'The Tell-Tale Heart'," collected in New Essays on Poe's Major Tales, Kenneth Silverman, ed. Cambridge University Press, 1993. ISBN 978-0-521-42243-7 p. 31-2

- ↑ Silverman, Kenneth. Edgar A. Poe: Mournful and Never-ending Remembrance. New York: Harper Perennial, 1991. p. 201 ISBN 0-06-092331-8

- ↑ Index to Poe's tales at Baltimore Poe Society Online

- ↑ "IMDb Title Search: The Tell-Tale Heart". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 2007-09-01.

- ↑ The Tell-Tale Heart (1953/I) on IMDb

- ↑ The Tell-Tale Heart (1960) on IMDb