Diacritic

á

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diacritic | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A diacritic[1] is a mark put above, below, through or on a letter. Some examples of diacritics are an acute accent or a grave accent. The word comes from the Greek word διακριτικός (transl. diakritikós, 'distinguishing'). Usually, it affects the way the word is said (pronounced). Most diacritics concern pronunciation because most alphabets do not describe the sounds of words exactly. Diacritics are rare in English, but common in many other languages.

Examples[change | change source]

English[change | change source]

English orthography often uses digraphs (like "ph", "sh", "oo", and "ea") rather than diacritics to show more sounds than can be shown with single letters of the Latin alphabet. Unlike other systems (such as Spanish) where the spelling shows how to say the words, English pronunciation is so varied that diacritics alone would not make it phonetic. By using digraphs we show sounds which are not shown by single letters.

Diacritics are not used much in modern English. Two types of diacritics have become part of everyday English: the dot above the "i" or "j" and the apostrophe. But they are no longer commonly thought of as being diacritical. The apostrophe is used to show missing letters (elision, it's to replace it is) and show possession (as in Mike's car).

In most other cases, use of diacritics for native English words is considered old-fashioned (not used anymore). Diaereses (similar to umlauts) can be used on words where two vowels next to each other are pronounced separately like noöne, reëstablished, or coöperate (two vowels pronounced together are a diphthong). This method is still used sometimes.[2] Diacritics are sometimes used in loanwords (words of foreign origin), such as naïve, entrée, pâté, façade,[3] which are French words.

French[change | change source]

Letter e: common are the acute accent é (rising voice, as in the French word née), grave accent è (lowering voice); élève has (from the left) acute, grave and silent e. The cedilla ç signals a soft c, sounding like an s in English.

A different principle is illustrated by the circumflex î. This usually shows the loss of letter: e.g. maistre (Middle French) > maître (modern French). Thus its function is historical. Also, less often, the circumflex is used to distinguish between homophones. These are words spelt the same, but with different meanings. Example: sur = on, but sûr = safe. In those cases the pronunciation of the two words may be different.

Spanish[change | change source]

In Spanish the acute accent simply signals stress, e.g. educación. There the stress is on the last vowel, not on the usual second to last. Second to last vowel (syllable) is the usual position for stress in spoken Spanish. It is usually not signalled by a printed accent. Where the stress is in its usual place, the end consonant is often dropped in speech.

The tilde ñ is pronounced something like ny. It counts as a separate letter in their dictionaries, coming after n.

The double L is pronounced as our Y and LL is in Spanish dictionaries in its own section, after the single L section.

German[change | change source]

The umlaut ü in German is pronounced ue, and is less used in modern German. Historical name-spellings should always keep the umlaut if it was used for that name.

Swedish, Norwegian, Danish[change | change source]

The Scandinavian languages treat the characters with diacritics ä, ö and å as new and separate letters of the alphabet, and sort them after z. Usually ä is sorted as equal to æ (ash) and ö is sorted as equal to ø (o-slash). Also, aa, when used as an alternative spelling to å, is sorted as such. Other letters modified by diacritics are treated as variants of the underlying letter, with the exception that ü is frequently sorted as y.

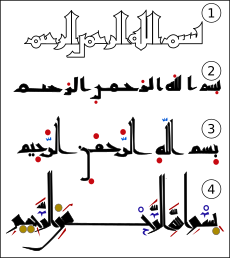

Non-Roman scripts[change | change source]

Letters in black, niqqud in red, cantillation in blue

Scripts for semitic languages such as Arabic and Hebrew have a wide variety of diacritics. This is partly because the scripts for semitic languages were originally formed without separate letters for vowels, and partly because some of the languages (Arabic in particular) are spoken in a number of dialects.

The diacritics in Hebrew and Arabic are not always used, however.

References[change | change source]

- ↑ /daɪəˈkrɪtɪk/

- ↑ Thomas Burns McArthur and Roshan McArthur (2005). Concise Oxford Companion to the English Language. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780192806376.

- ↑ Dr Lim Chin Lam (11 November 2011). "How foreign is English?". The Star. Archived from the original on 13 May 2012. Retrieved 17 June 2012.