List of landmark court decisions in the United States

The following is a partial list of landmark court decisions in the United States. Landmark decisions establish a significant new legal precedent or concept. They can also substantially change the interpretation of existing law. Such a decision may settle the law in more than one way:

- By distinguishing a new principle that refines a prior principle. This way it can depart from prior practice without violating the rule of stare decisis.

- Or, by establishing a test case (a case used to set a precedent) or a measurable standard that can be applied by courts in future decisions.

In the United States, landmark court decisions come most frequently from the Supreme Court. Sometimes United States courts of appeals make such decisions, particularly if the Supreme Court chooses not to review the case or if it adopts the holding of the lower court. Although many cases from state supreme courts are significant in developing the law of that state, only a few are so radically different that they announce standards that many other state courts then choose to follow.

Individual rights[change | change source]

Discrimination based on race or ethnicity[change | change source]

The Supreme Court has dealt with many cases of discrimination based on race or ethnicity. This is a partial list of such cases.

Basic rights[change | change source]

- Dred Scott v. Sandford, 60 U.S. 393 (1857), People of African descent that are slaves or were slaves and subsequently freed, along with their descendants, cannot be United States citizens.[1] For that reason, they cannot sue in federal court. Also, slavery cannot be prohibited in the western territories before they become states. After the Civil War, this decision was voided by the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution.[2]

- Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3 (1883), Neither the Thirteenth nor the Fourteenth Amendment empower Congress to safeguard blacks against the actions of private individuals.

- Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214 (1944), President Franklin D. Roosevelt's Executive Order 9066 is constitutional; therefore, American citizens of Japanese descent can be interned and deprived of their basic constitutional rights.[3] This case featured the first application of strict scrutiny to racial discrimination by the government.

- Hernandez v. Texas 347 U.S. 475 (1954), Mexican Americans and all other racial and national groups in the United States have equal protection under the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. The protection of the 14th Amendment covers any racial, national and ethnic groups of the United States for which discrimination can be proved.[4]

- Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U.S. 157 (1961), Peaceful sit-in demonstrators protesting segregationist policies cannot be arrested under a state's "disturbing the peace" laws.[5]

- Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967) Laws that prohibit interracial marriage (Anti-miscegenation laws) are unconstitutional.[6]

Segregation (public transportation)[change | change source]

- Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896) State laws requiring segregated facilities for blacks and whites are constitutional under the doctrine of separate but equal.[7] The ruling held for nearly 60 years. (Partially overruled by Brown v. Board of Education (1954))

- Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U.S. 373 (1946) A Virginia law that enforces segregation on interstate buses is unconstitutional.

- Henderson v. United States, 339 U.S. 816 (1950) The Interstate Commerce Act of 1887 makes it unlawful for a railroad that engages in interstate commerce to subject any particular person to any undue or unreasonable prejudice or disadvantage in any respect whatsoever.

- Sarah Keys v. Carolina Coach Company, 64 MCC 769 (1955) According to the Interstate Commerce Commission, the non-discrimination language of the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887 bans racial segregation on buses traveling across state lines. The Supreme Court later adopted and expanded this decision in Boynton v. Virginia (1960).

- Browder v. Gayle, 142 F. Supp. 707 (M.D. Ala. 1956) Bus segregation is unconstitutional under the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

- Boynton v. Virginia, 364 U.S. 454 (1960) Racial segregation in all forms of public transportation is illegal under the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887.[8]

Segregation (housing)[change | change source]

- Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948) Courts may not enforce racial covenants on real estate.

- Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409 (1968) The federal government may prohibit discrimination in housing by private parties under the Civil Rights Act of 1968.

- Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265 (1978) Race-based set-asides in educational opportunities violate the Equal Protection Clause. This decision leaves the door open for the possibility of some use of race in admission decisions.

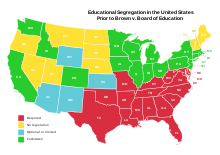

Segregation (schools)[change | change source]

- Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) Segregated schools in the states are unconstitutional because they violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.[9] At least as applied to public schools, the court overruled Plessy v. Ferguson.[9] A year later in:

- Brown v. Board of Education II, 349 U.S. 294 (1955), the court ordered school integration for all states "with all deliberate speed."[9]

- Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 (1954) Segregated schools in the District of Columbia violate the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment.

- Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1 (1971) The busing of students to promote racial integration in public schools is constitutional.

- Adarand Constructors, Inc. v. Peña, 515 U.S. 200 (1995) Race-based discrimination, including discrimination in favor of minorities (affirmative action), must pass strict scrutiny.

- Grutter v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 306 (2003) A narrowly tailored use of race in student admission decisions may be permissible under the Equal Protection Clause because a diverse student body is beneficial to all students. This was hinted at in Regents v. Bakke (1978).

- Schuette v. Coalition to Defend Affirmative Action, 572 U.S. ___ (2014) A Michigan state constitutional amendment that bans affirmative action does not violate the Equal Protection Clause.

- Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard, 600 U.S. ___ (2023) and Students for Fair Admissions v. University of North Carolina, 600 U.S. ___ (2023) Race-based affirmative action programs in non-military college admissions processes violate the Equal Protection Clause.

Voting rights[change | change source]

- Smith v. Allwright, 321 U.S. 649 (1944) This case looked at the Texas Democratic Party's policy of preventing black people from voting in primary elections. The court decided this practice violated the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments.[10]

- Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 (1960) Electoral district boundaries drawn only to disenfranchise blacks violate the Fifteenth Amendment.

Other issues[change | change source]

- New Negro Alliance v. Sanitary Grocery Co., 303 U.S. 552 (1938) Persons having a direct or indirect interest in terms and conditions of employment have the liberty to advertise and disseminate facts and information with respect to terms and conditions of employment, and peacefully to persuade others to concur in their views respecting an employer's practices.

- Gates v. Collier, 501 F. 2d 1291 (5th Cir. 1974) This decision brought an end to the trusty system and flagrant inmate abuse at the Mississippi State Penitentiary in Parchman, Mississippi. It was the first body of law developed in the Fifth Circuit that abolished racial segregation in prisons and held that a variety of forms of corporal punishment against prisoners is considered cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the Eighth Amendment.

- Batson v. Kentucky, 476 U.S. 79 (1986) Prosecutors may not use peremptory challenges to dismiss jurors based on their race.

Discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity[change | change source]

- Bowers v. Hardwick, 478 U.S. 186 (1986) A Georgia law that criminalizes certain acts of private sexual conduct between homosexual persons does not violate the Fourteenth Amendment. (Overruled by Lawrence v. Texas (2003))

- Romer v. Evans, 517 U.S. 620 (1996) A Colorado state constitutional amendment that prevents homosexuals and bisexuals from being able to obtain protections under the law is a violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

- Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U.S. 558 (2003) A Texas law that criminalizes consensual same-sex sexual conduct furthers no legitimate state interest and violates homosexuals' right to privacy under the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. This decision invalidates all of the remaining sodomy laws in the United States.

- Goodridge v. Department of Public Health, 440 Mass. 309 (2003) The denial of marriage licenses to same-sex couples violates provisions of the state constitution guaranteeing individual liberty and equality.[11] It is not rationally related to a legitimate state interest. This was the first state court decision in which same-sex couples won the right to marry.

- United States v. Windsor, 570 U.S. ___ (2013) Ruled on Section 3 of the Defense of Marriage Act, which defines—for federal law purposes—the terms "marriage" and "spouse" to apply only to marriages between one man and one woman. The court ruled the law deprives same-sex couples, who are legally married under state law, of their Fifth Amendment guarantee of equal protection.[12] The federal government must recognize same-sex marriages that have been approved by the states.[13]

- Obergefell v. Hodges, 576 U.S. ___ (2015) In Ohio, Michigan, Kentucky, and Tennessee, groups of same-sex couples sued over their right to marry.[14] They said the states violated the Equal Protection and Due Process Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment.[14] The court agreed and held the right to marry is a fundamental right protected by the Constitution.[14]

- Bostock v. Clayton County, 590 U.S. ___ (2020), R.G. & G.R. Harris Funeral Homes Inc. v. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, 590 U.S. ___ (2020), and Altitude Express, Inc. v. Zarda, 590 U.S. ___ (2020), Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 protects employees against discrimination due to their sexual orientation or gender identity. The Supreme Court ruled under Bostock but the ruling covered all three cases.

Birth control and abortion[change | change source]

- Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 (1965) A Connecticut law that criminalizes the use of contraception by married couples is unconstitutional because all Americans have a constitutionally protected right to privacy. This interpretation of a constitutional right to privacy led to the more famous case brought by Jane Roe against prosecutor Henry Wade.[15]

- Eisenstadt v. Baird, 405 U.S. 438 (1972) A Massachusetts law that criminalizes the use of contraception by unmarried couples violates the right to privacy established in Griswold as well as the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

- Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973) The court ruled that a state law that banned abortions (except to save the life of the mother) was unconstitutional.[16] The ruling made abortion legal in many circumstances.

- Carey v. Population Services International, 431 U.S. 678 (1977) Laws that restrict the sale, distribution, and advertisement of contraceptives to both adults and minors are unconstitutional.

- Planned Parenthood v. Casey, 505 U.S. 833 (1992) A woman is still able to have an abortion before viability, but several restrictions are now permitted during the first trimester. The strict trimester framework of Roe is discarded and replaced with the more vague "undue burden" test.

- Stenberg v. Carhart, 530 U.S. 914 (2000) Laws that ban partial-birth abortion are unconstitutional if they do not make an exception for the woman's health or if they cannot be reasonably construed to apply only to the partial-birth abortion procedure and not to other abortion methods.

- Gonzales v. Carhart, 550 U.S. 124 (2007) The Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act of 2003 is constitutional because it is less ambiguous than the law that was struck down in Stenberg. It is not vague or too broad. It does not impose an undue burden on a woman's right to choose to have an abortion.

- Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc., 573 U.S. ___ (2014) Closely held corporations have free exercise rights under the Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993. As applied to such corporations, the requirement of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act that employers provide their female employees with no-cost access to contraception violates the Religious Freedom Restoration Act.

- Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization, 597 U.S. ___ (2022) The constitution does not give a right to abortion. This over-ruled Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey.

End of life[change | change source]

- Cruzan v. Director, Missouri Department of Health, 497 U.S. 261 (1990) When a family has requested the termination of life-sustaining treatments for their vegetative relative, the state may constitutionally oppose this request if there is not evidence that the relative would have wanted that.

- Washington v. Glucksberg, 521 U.S. 702 (1997) Washington's prohibition on assisted suicide is constitutional.

- Vacco v. Quill, 521 U.S. 793 (1997) New York's prohibition on assisted suicide does not violate the Equal Protection Clause.

- Gonzales v. Oregon, 546 U.S. 243 (2006) The Controlled Substances Act does not prevent physicians from being able to prescribe the drugs needed to perform assisted suicides under state law.

Power of Congress to enforce civil rights[change | change source]

- Heart of Atlanta Motel, Inc. v. United States, 379 U.S. 241 (1964) The Civil Rights Act of 1964 applies to places of public accommodation patronized by interstate travelers by reason of the Commerce Clause in Article One of the Constitution (Section 8, Clause 3).

- Katzenbach v. McClung, 379 U.S. 294 (1964) The power of Congress to regulate interstate commerce extends to a restaurant that is not patronized by interstate travelers but which serves food that has moved in interstate commerce. This ruling makes the Civil Rights Act of 1964 apply to virtually all businesses.

- South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301 (1966) The Voting Rights Act of 1965 is a valid use of Congress's power under Section 2 of the Fifteenth Amendment.

- Katzenbach v. Morgan, 384 U.S. 641 (1966) Congress may enact laws stemming from Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment that increase the rights of citizens beyond what the judiciary has recognized.

- City of Boerne v. Flores, 521 U.S. 507 (1997) Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment does not permit Congress to substantially increase the scope of the rights determined by the judiciary. Congress may only enact remedial or preventative measures that are consistent with the Fourteenth Amendment interpretations of the Supreme Court.

- Shelby County v. Holder, 570 U.S. ___ (2013) Section 4(b) of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which contains the coverage formula that determines which state and local jurisdictions are subjected to federal preclearance from the Department of Justice before implementing any changes to their voting laws or practices based on their histories of racial discrimination in voting, is unconstitutional because it no longer reflects current societal conditions.

General rights and freedoms[change | change source]

Basic rights[change | change source]

- Corfield v. Coryell, 6 Fed. Cas. 546 (C.C.E.D. Pa. 1823) Some of the rights protected by the Privileges and Immunities Clause in Article Four of the Constitution (Section 2, Clause 1) include the freedom of movement through the states, the right of access to the courts, the right to purchase and hold property, an exemption from higher taxes than those paid by state residents, and the right to vote.

- Schenck v. United States, 249 U.S. 47 (1919) Speech is not protected under the First Amendment if it causes a danger to other people. Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. famously used the comparison that free speech would not protect a person from shouting "fire" in a crowded theater and starting a panic.

Citizenship rights[change | change source]

- United States v. Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. 649 (1898) With only a few narrow exceptions, every person born in the United States becomes a United States citizen at birth because of the Citizenship Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

- Afroyim v. Rusk, 387 U.S. 253 (1967) The right of citizenship is protected by the Citizenship Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Congress has no power under the Constitution to take away a person's United States citizenship unless he or she voluntarily relinquishes (gives it up) it.[17]

Freedom to travel[change | change source]

- Crandall v. Nevada, 73 U.S. 35 (1868) The freedom of movement is a fundamental right; a state cannot inhibit people from leaving the state by taxing them.

- United States v. Wheeler, 254 U.S. 281 (1920) The Constitution grants to the states the power to prosecute individuals for wrongful interference with the right to travel.

- Edwards v. California, 314 U.S. 160 (1941) A state cannot prohibit indigent people from moving into it.

- Kent v. Dulles, 357 U.S. 116 (1958) The right to travel is a part of the "liberty" of which the citizen cannot be deprived without due process of law under the Fifth Amendment.

- Aptheker v. Secretary of State, 378 U.S. 500 (1964) First case in which the U.S. Supreme Court considered the constitutionality of personal restrictions on the right to travel abroad and passport restrictions as they relate to Fifth Amendment due process rights and First Amendment free speech, freedom of assembly, and freedom of association rights.

- United States v. Guest, 383 U.S. 745 (1966) There is a constitutional right to travel from state to state, and the protections of the Fourteenth Amendment extend to citizens who suffer rights deprivations at the hands of private conspiracies where there is minimal state participation in the conspiracy.

[change | change source]

- Ex parte Milligan, 71 U.S. 2 (1866) Trying citizens in military courts is unconstitutional when civilian courts are still operating. Trial by military tribunal is constitutional only when there is no power left but the military, and the military may validly try criminals only as long as is absolutely necessary.

- Reid v. Covert, 354 U.S. 1 (1957) United States citizens abroad, even when associated with the military, cannot be deprived of the protections of the Constitution and cannot be made subject to military jurisdiction.

Other issues[change | change source]

- Gates v. Collier, 501 F.2d 1291 (5th Circuit 1974) A variety of forms of corporal punishment against prisoners constituted cruel and unusual punishment and a violation of Eighth Amendment rights. This ruling ended the Trusty system and the flagrant inmate abuse that accompanied it at in states using the trusty system as a replacement for the convict lease system.

- O'Connor v. Donaldson, 422 U.S. 563 (1975) The states cannot involuntarily commit individuals if they are not a danger to themselves or others and are capable of living by themselves or with the aid of responsible family members or friends.

- Olmstead v. L.C., 527 U.S. 581 (1999) Under the Americans with Disabilities Act, people with intellectual disabilities must be allowed to live in the community if they can. If they can live in the community, keeping them in institutions is segregation and is discrimination.

Criminal law[change | change source]

Freedom from unreasonable searches and seizures[change | change source]

- Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U.S. 643 (1961) Evidence that is obtained in violation of the Fourth Amendment is inadmissible in state court.

- Schmerber v. California, 384 U.S. 757 (1966) The application of the Fourth Amendment's protection against warrantless searches and the Fifth Amendment privilege against self incrimination to searches that intrude into the human body means that police may not conduct warrantless blood testing on suspects absent an emergency that justifies acting without a warrant.

- Katz v. United States, 389 U.S. 347 (1967) The Fourth Amendment's ban on unreasonable searches and seizures applies to all places where an individual has a "reasonable expectation of privacy."

- Terry v. Ohio, 392 U.S. 1 (1968) Police may stop a person if they have a reasonable suspicion that the person has committed or is about to commit a crime and frisk the suspect for weapons if they have a reasonable suspicion that the suspect is armed and dangerous without violating the Fourth Amendment.

- Bivens v. Six Unknown Named Agents, 403 U.S. 388 (1971) Individuals may sue federal government officials who have violated their Fourth Amendment rights even though such a suit is not authorized by law. The existence of a remedy for the violation is implied from the importance of the right that is violated.

- United States v. United States District Court for the Eastern District of Michigan, 407 U.S. 297 (1972) Government officials must obtain a warrant before beginning electronic surveillance even if domestic security issues are involved. The "inherent vagueness of the domestic security concept" and the potential for abusing it to quell political dissent make the Fourth Amendment's protections especially important when the government engages in spying on its own citizens.

- Illinois v. Gates, 462 U.S. 213 (1983) The totality of the circumstances, rather than a rigid test, must be used in finding probable cause under the Fourth Amendment.

- New Jersey v. T. L. O., 469 U.S. 325 (1985) The Fourth Amendment's ban on unreasonable searches applies to those conducted by public school officials as well as those conducted by law enforcement personnel, but public school officials can use the less strict standard of reasonable suspicion instead of probable cause.

- Vernonia School District 47J v. Acton, 515 U.S. 646 (1995) Schools may implement random drug testing upon students participating in school-sponsored athletics.

- Board of Education v. Earls, 536 U.S. 822 (2002) Coercive drug testing imposed by school districts upon students who participate in extracurricular activities does not violate the Fourth Amendment.

- Georgia v. Randolph, 547 U.S. 103 (2006) Police cannot conduct a warrantless search in a home where one occupant consents and the other objects.

- In re Directives, (2008) According to the United States Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court of Review, an exception to the Fourth Amendment’s warrant requirement exists when surveillance is conducted to obtain foreign intelligence for national security purposes and is directed against foreign powers or agents of foreign powers reasonably believed to be located outside the United States.[18]

- United States v. Jones, 565 U.S. ___ (2012) Attaching a GPS device to a vehicle and then using the device to monitor the vehicle’s movements constitutes a search under the Fourth Amendment.

- Riley v. California, 573 U.S. ___ (2014) Police must obtain a warrant in order to search digital information on a cell phone seized from an individual who has been arrested.

Right to an attorney[change | change source]

- Glasser v. United States, 315 U.S. 60 (1942) A defense lawyer's conflict of interest arising from a simultaneous representation of codefendants violates the Assistance of Counsel Clause of the Sixth Amendment.

- Betts v. Brady, 316 U.S. 455 (1942) Indigent defendants may be denied counsel when prosecuted by a state. (Overruled by Gideon v. Wainwright (1963))

- Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963) All defendants have the right to an attorney and must be provided one by the state if they are unable to afford legal counsel.

- Escobedo v. Illinois, 378 U.S. 478 (1964) A person in police custody has the right to speak to an attorney.

- Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966) Police must advise criminal suspects of their rights under the Constitution to remain silent, to consult with a lawyer, and to have one appointed to them if they are indigent. A police interrogation must stop if the suspect states that he or she wishes to remain silent.

- In re Gault, 387 U.S. 1 (1967) Juvenile defendants are protected under the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

- Michigan v. Jackson, 475 U.S. 625 (1986) If a police interrogation begins after a defendant asserts his or her right to counsel at an arraignment or similar proceeding, then any waiver of that right for that police-initiated interrogation is invalid. (Overruled by Montejo v. Louisiana (2009))

- Montejo v. Louisiana, 556 U.S. 778 (2009) A defendant may waive his or her right to counsel during a police interrogation even if the interrogation begins after the defendant's assertion of his or her right to counsel at an arraignment or similar proceeding.

Other rights regarding counsel[change | change source]

- Strickland v. Washington, 466 U.S. 668 (1984) To obtain relief due to ineffective assistance of counsel, a criminal defendant must show that counsel's performance fell below an objective standard of reasonableness and that counsel's deficient performance gives rise to a reasonable probability that, if counsel had performed adequately, the result of the proceeding would have been different.

- Padilla v. Kentucky, 559 U.S. 356 (2010) Criminal defense attorneys are duty-bound to inform clients of the risk of deportation under three circumstances. First, where the law is unambiguous, attorneys must advise their criminal clients that deportation "will" result from a conviction. Second, where the immigration consequences of a conviction are unclear or uncertain, attorneys must advise that deportation "may" result. Finally, attorneys must give their clients some advice about deportation—counsel cannot remain silent about immigration consequences.

Right to remain silent[change | change source]

- Berghuis v. Thompkins, 560 U.S. 370 (2010) The right to remain silent does not exist unless a suspect invokes it unambiguously.

- Salinas v. Texas, 570 U.S. ___ (2013) The Fifth Amendment's protection against self-incrimination does not protect an individual's refusal to answer questions asked by law enforcement before he or she has been arrested or given the Miranda warning. A witness cannot invoke the privilege by simply standing mute; he or she must expressly invoke it.

Competence[change | change source]

- Dusky v. United States, 362 U.S. 402 (1960) A defendant has the right to a competency evaluation before proceeding to trial.

- Rogers v. Okin, 478 F. Supp. 1342 (D. Mass. 1979) The competence of a committed patient is presumed until he or she is adjudicated incompetent.

- Ford v. Wainwright, 477 U.S. 399 (1986) A defendant has the right to a competency evaluation before being executed.

- Godinez v. Moran, 509 U.S. 389 (1993) A defendant who is competent to stand trial is automatically competent to plead guilty or waive the right to legal counsel.

- Kahler v. Kansas, 589 U.S. ___ (2020) The Constitution's Due Process Clause does not necessarily compel the acquittal of any defendant who, because of mental illness, could not tell right from wrong when committing their crime.

Detainment of terrorism suspects[change | change source]

- Rasul v. Bush, 542 U.S. 466 (2004) The federal court system has the authority to decide if foreign nationals held at Guantanamo Bay were wrongfully imprisoned.

- Hamdi v. Rumsfeld, 542 U.S. 507 (2004) The federal government has the power to detain those it designates as enemy combatants, including United States citizens, but detainees that are United States citizens must have the rights of due process and the ability to challenge their enemy combatant status before an impartial authority.

- Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, 548 U.S. 557 (2006) The military commissions set up by the Bush administration to try detainees at Guantanamo Bay are illegal because they lack the protections that are required by the Geneva Conventions and the Uniform Code of Military Justice.

- Boumediene v. Bush, 553 U.S. 723 (2008) Foreign terrorism suspects held at Guantanamo Bay have the constitutional right to challenge their detention in United States courts.

Capital punishment[change | change source]

- Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 238 (1972) The arbitrary and inconsistent imposition of the death penalty violates the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments and constitutes cruel and unusual punishment. This decision initiates a nationwide de facto moratorium on executions that lasts until the Supreme Court's decision in Gregg v. Georgia (1976).

- Gregg v. Georgia, 428 U.S. 153 (1976) Georgia's new death penalty statute is constitutional because it adequately narrows the class of defendants eligible for the death penalty. This case and the next four cases were consolidated and decided simultaneously. By evaluating the new death penalty statutes that had been passed by the states, the Supreme Court ended the moratorium on executions that began with its decision in Furman v. Georgia (1972).

- Proffitt v. Florida, 428 U.S. 242 (1976) Florida's new death penalty statute is constitutional because it requires the comparison of aggravating factors to mitigating factors in order to impose a death sentence.

- Jurek v. Texas, 428 U.S. 262 (1976) Texas's new death penalty statute is constitutional because it uses a three-part test to determine if a death sentence should be imposed.

- Woodson v. North Carolina, 428 U.S. 280 (1976) North Carolina's new death penalty statute is unconstitutional because it allows a mandatory death sentence to be imposed.

- Roberts v. Louisiana, 428 U.S. 325 (1976) Louisiana's new death penalty statute is unconstitutional because it calls for a mandatory death sentence for a large range of crimes.

- Coker v. Georgia, 433 U.S. 584 (1977) A death sentence may not be imposed for the crime of rape.

- Enmund v. Florida, 458 U.S. 782 (1982) A death sentence may not be imposed on offenders who are involved in a felony during which a murder is committed but who do not actually kill, attempt to kill, or intend that a killing take place.

- Ford v. Wainwright, 477 U.S. 399 (1986) A death sentence may not be imposed on the insane.

- Breard v. Greene, 523 U.S. 371 (1998) The International Court of Justice does not have jurisdiction in capital punishment cases that involve foreign nationals.

- Atkins v. Virginia, 536 U.S. 304 (2002) A death sentence may not be imposed on mentally retarded offenders, but the states can define what it means to be mentally retarded.

- Roper v. Simmons, 543 U.S. 551 (2005) A death sentence may not be imposed on juvenile offenders.

- Baze v. Rees, 553 U.S. 35 (2008) The three-drug cocktail used for performing executions by lethal injection in Kentucky (as well as virtually all of the states using lethal injection at the time) is constitutional under the Eighth Amendment.

- Kennedy v. Louisiana, 554 U.S. 407 (2008) The death penalty is unconstitutional in all cases that do not involve murder or crimes against the state such as treason.

Other criminal sentences[change | change source]

- Apprendi v. New Jersey, 530 U.S. 466 (2000) Other than the fact of a prior conviction, any fact that increases the penalty for a crime beyond the prescribed statutory maximum must be submitted to a jury and proved beyond a reasonable doubt.

- Graham v. Florida, 560 U.S. 48 (2010) A sentence of life imprisonment without the possibility of parole may not be imposed on juvenile non-homicide offenders.

- Miller v. Alabama, 567 U.S. ___ (2012) A sentence of life imprisonment without the possibility of parole may not be a mandatory sentence for juvenile offenders.

- Ramos v. Louisiana, 590 U.S. ___ (2020) The Sixth Amendment right to jury trial is read as requiring a unanimous verdict to convict a defendant of a serious offense and is an incorporated right to the states.

Federalism[change | change source]

Unconstitutional laws[change | change source]

- Ware v. Hylton, 3 U.S. 199 (1796) A section of the Treaty of Paris supersedes an otherwise valid Virginia statute under the Supremacy Clause in Article Six, Clause 2 of the Constitution. This case featured the first example of judicial nullification of a state law.

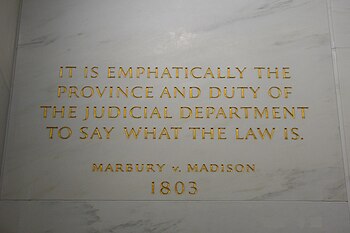

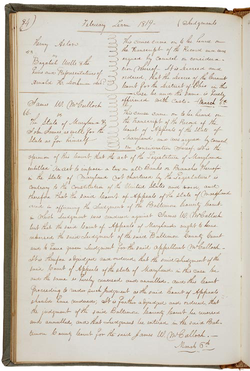

- Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. 137 (1803) Section 13 of the Judiciary Act of 1789 is unconstitutional because it attempts to expand the original jurisdiction of the Supreme Court beyond that permitted by the Constitution. Congress cannot pass laws that contradict the Constitution. This case featured the first example of judicial nullification of a federal law. It is also the point at which the Supreme Court adopted a monitoring role over government actions.[19]

- Fletcher v. Peck, 10 U.S. 87 (1810) A state legislature can repeal a corruptly made law, but the Contract Clause of the Constitution prohibits the voiding of valid contracts made under such a law. This was the first case in which the Supreme Court struck down a state law as unconstitutional.

- United States v. Lopez, 514 U.S. 549 (1995) The Gun-Free School Zones Act of 1990 is unconstitutional. The Commerce Clause of the Constitution does not give Congress the power to prohibit the mere possession of a gun near a school, because gun possession by itself is not an economic activity that affects interstate commerce even indirectly.

- U.S. Term Limits, Inc. v. Thornton, 514 U.S. 779 (1995) The states cannot create qualifications for prospective members of Congress that are stricter than those specified in the Constitution. This decision invalidates provisions that had imposed term limits on members of Congress in 23 states.

- Printz v. United States, 521 U.S. 898 (1997) The interim provision of the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act that requires state and local officials to conduct background checks on firearm purchasers violates the Tenth Amendment.

- Clinton v. City of New York, 524 U.S. 417 (1998) The Line Item Veto Act of 1996 is unconstitutional because it allows the President to amend or repeal parts of statutes without the pre-approval of Congress. According to the Presentment Clause of the Constitution, Congress must initiate all changes to existing laws.

- United States v. Morrison, 529 U.S. 598 (2000) The section of the Violence Against Women Act of 1994 that gives victims of gender-motivated violence the right to sue their attackers in federal court is an unconstitutional intrusion on states' rights, and it cannot be saved by the Commerce Clause or Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment.

- National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius, 567 U.S. ___ (2012) The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act's expansion of Medicaid is unconstitutional as-written—it is unduly coercive to force the states to choose between participating in the expansion or forgoing all Medicaid funds. In addition, the individual health insurance mandate is constitutional by virtue of the Taxing and Spending Clause in Article One, Section 8, Clause 1 (though not by the Commerce Clause or the Necessary and Proper Clause).

State powers[change | change source]

- Pollock v. Farmers' Loan & Trust Co., 157 U.S. 429 (1895) Income taxes on interest, dividends, and rents are, in effect, direct taxes that must be apportioned among the states according to their populations. This decision was voided by the Sixteenth Amendment in 1913, allowing income taxes to be implemented without apportionment.

- United States v. Wheeler, 254 U.S. 281 (1920) The Constitution grants to the states the power to prosecute individuals for wrongful interference with the right to travel.

- Oregon v. Mitchell, 400 U.S. 112 (1970) Congress has the power to regulate requirements for voting in federal elections, but it is prohibited from regulating requirements for voting in state and local elections. This decision led to the ratification of the Twenty-sixth Amendment in 1971, which lowered the minimum voting age to 18 for all elections.

- Heath v. Alabama, 474 U.S. 82 (1985) The Double Jeopardy Clause of the Fifth Amendment does not prohibit two different states from separately prosecuting and convicting the same individual for the same illegal act.

Limits on state powers[change | change source]

- Chisholm v. Georgia, 2 U.S. 419 (1793) The Constitution prevents the states from exercising sovereign immunity. Therefore, the states can be sued in federal court by citizens of other states. This decision was voided by the Eleventh Amendment in 1795, just two years after it was handed down.

- McCulloch v. Maryland, 17 U.S. 316 (1819) The Necessary and Proper Clause of the Constitution (Article One, Section 8, Clause 18) grants to Congress implied powers for implementing the Constitution's express powers, and state actions may not impede valid exercises of power by the federal government.

- Barron v. Baltimore, 32 U.S. 243 (1833) The Bill of Rights cannot be applied to the state governments. This decision has essentially been rendered moot by the Supreme Court's adoption of the incorporation doctrine, which uses the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to apply portions of the Bill of Rights to the states.

- Cooley v. Board of Wardens, 53 U.S. 299 (1852) When local circumstances make it necessary, the states can regulate interstate commerce, as long as such regulations do not conflict with federal law. State laws related to commerce powers can be valid if Congress is silent on the matter.

- Ableman v. Booth, 62 U.S. 506 (1859) State courts cannot issue rulings that contradict the decisions of federal courts.

- Texas v. White, 74 U.S. 700 (1869) The states that formed the Confederate States of America during the Civil War never actually left the Union because a state cannot unilaterally secede from the United States.

- Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958) The states are bound by the decisions of the Supreme Court and cannot choose to ignore them.

- Arizona v. United States, 567 U.S. ___ (2012) An Arizona law that authorizes local law enforcement to enforce immigration laws is preempted by federal law. Arizona law enforcement may inquire about a resident's legal status during lawful encounters, but the state may not implement its own immigration laws.

Federal judiciary powers[change | change source]

- Martin v. Hunter's Lessee, 14 U.S. 304 (1816) Federal courts may review state court decisions when they rest on federal law or the federal Constitution. This decision provides for the uniform interpretation of federal law throughout the states.

- Ex parte Young, 209 U.S. 123 (1908) Sovereign immunity cannot be used to bar suits against state officials for injunctive relief under the Constitution when said officials were not acting on behalf of the state when they sought to enforce an unconstitutional law.

Federal Congressional powers[change | change source]

- Hylton v. United States, 3 U.S. 171 (1796) A tax on the possession of goods is not a direct tax that the federal government must split up among the states according to their populations. This case featured the first example of judicial review by the Supreme Court.

- Gibbons v. Ogden, 22 U.S. 1 (1824) The power to regulate interstate navigation is granted to Congress by the Commerce Clause of the Constitution.

- Swift and Company v. United States, 196 U.S. 375 (1905) Congress can prohibit local business practices in order to regulate interstate commerce because those practices, when combined together, form a "stream of commerce" between the states. (Superseded by National Labor Relations Board v. Jones & Laughlin Steel Corporation (1937))

- Missouri v. Holland, 252 U.S. 416 (1920) Treaties made by the federal government are supreme over any concerns brought by the states about such treaties interfering with any states' rights derived from the Tenth Amendment.

- J. W. Hampton, Jr. & Co. v. United States, 276 U.S. 394 (1928) The Separation of Powers can be side-stepped if Congress provides an "intelligible principle" to guide the executive branch.

- National Labor Relations Board v. Jones & Laughlin Steel Corporation, 301 U.S. 1 (1937) The National Labor Relations Act and, by extension, the National Labor Relations Board are constitutional because the Commerce Clause applies to labor relations. Therefore, the NLRB has the right to sanction companies that fire or discriminate against workers for belonging to a union. Also, a local commercial activity that is considered in isolation may still constitute interstate commerce if that activity has a "close and substantial relationship" to interstate commerce.

- Steward Machine Company v. Davis, 301 U.S. 548 (1937) The federal government is permitted to impose a tax even if the goal of the tax is not just the collection of revenue.

- United States v. Darby Lumber Co., 312 U.S. 100 (1941) Control over interstate commerce belongs entirely to Congress. The Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 is constitutional under the Commerce Clause because it prevents the states from lowering labor standards to gain commercial advantages.

- Wickard v. Filburn, 317 U.S. 111 (1942) The Commerce Clause of the Constitution allows Congress to regulate anything that has a substantial economic effect on commerce, even if that effect is indirect.

- South Dakota v. Dole, 483 U.S. 203 (1987) Congress may attach reasonable conditions to funds disbursed to the states without violating the Tenth Amendment.

- Gonzales v. Raich, 545 U.S. 1 (2005) Congress may ban the use of marijuana even in states that have approved its use for medicinal purposes.

Notes[change | change source]

References[change | change source]

- ↑ "Dred Scott v. Sanford". Oyez. Legal Information Institute. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ↑ Lawrence K. Furbish (25 September 1996). "OLR Research Report". The Connecticut General Assembly. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- ↑ "Korematsu v. United States (1944)". PBS/Educational Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 14 February 2016.

- ↑ "Hernandez v. Texas". IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

- ↑ "First Amendment Timeline" (PDF). Annenbergclassroom.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-04-21. Retrieved 2013-11-03.

- ↑ "Loving v. Virginia: The Case over Interracial Marriage". American Civil Liberties Union. Archived from the original on 20 April 2016. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- ↑ "Plessy v. Ferguson – Case Brief Summary". Lawnix. Archived from the original on 25 May 2009. Retrieved 14 February 2016.

- ↑ Cristina Vignone. "History of the Civil Rights Movement: Boynton v. Virginia". Fordham University. Archived from the original on 25 August 2016. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 "Brown v. Board of Education (1954)". PBS/ Educational Broadcasting Corporation. December 2006. Retrieved 14 February 2016.

- ↑ "Landmark: Smith v. Allwright". NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. Retrieved 14 February 2016.

- ↑ "Goodridge v. Dept. of Public Health". CaseBriefSummary.com. 6 November 2012. Archived from the original on 26 March 2016. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- ↑ "United States v. Windsor". Chicago-Kent College of Law. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- ↑ Marci A. Hamilton (28 June 2013). "How to Read United States v. Windsor to Understand What Gay Couples Won This Week, But Why They Still Have a Long Way to Go". Justia. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 "Obergefell v. Hodges". IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- ↑ Mark Kogan (22 January 2013). "Roe v. Wade: A Simple Explanation Of the Most Important SCOTUS Decision in 40 Years". Mic Network Inc. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- ↑ "Roe v. Wade (1973)". PBS/Educational Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- ↑ "Afroyim v. Rusk". Legal Information Institute, Cornell University Law School. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- ↑ Selya, Bruce M. (August 22, 2008). "United States Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court of Review Case No. 08-01 In Re Directives [redacted text] Pursuant to Section 105B of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act" (PDF). United States Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court of Review (via the Federation of American Scientists). Retrieved July 15, 2013.

- ↑ Laura Langer, Judicial Review in State Supreme Courts: A Comparative Study (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2002), p. 4