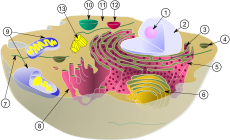

Mitochondria

(1) Nucleolus

(2) Nucleus

(3) Ribosomes

(4) Vesicle

(5) Rough endoplasmic reticulum (ER)

(6) Golgi apparatus

(7) Cytoskeleton

(8) Smooth ER

(9) Mitochondria

(10) Vacuole

(11) Cytoplasm

(12) Lysosome

(13) Centrioles within centrosome

Mitochondria [1] (sing. mitochondrion) are organelles, or parts of a eukaryote cell. They are in the cytoplasm, not the nucleus.

They make most of the cell's supply of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), a molecule that cells use as a source of energy. Their main job is to convert energy. They oxidise glucose to provide energy for the cell. The process makes ATP, and is called cellular respiration.[2] This means mitochondria are known as "the powerhouse of the cell".[3]

In addition to supplying cellular energy, mitochondria are involved in a range of other processes, such as signalling, cellular differentiation, cell death, as well as the control of the cell division cycle and cell growth.[4]

Structure[change | change source]

A mitochondrion contains two membranes. These are made of phospholipid double layers and proteins. The two membranes have different properties. Because of this double-membraned organization, there are five distinct compartments within the mitochondrion. They are:

- the outer mitochondrial membrane,

- the intermembrane space (the space between the outer and inner membranes),

- the inner mitochondrial membrane,

- the cristae space (formed by infoldings of the inner membrane), and

- the matrix (space within the inner membrane). Mitochondria are small, spherical or cylindrical organelles. Generally a mitochondrion is 2.8 microns long and about 0.5 microns wide. it is about 150 times smaller than the nucleus. There are about 100-150 mitochondria in each cell.

Function[change | change source]

The mitochondria's main role in the cell is to take glucose and use the energy they stored in its chemical bonds to make ATP in a process called cellular respiration. There are 3 main steps to this process: glycolysis, the citric acid cycle or Krebs cycle, and ATP Synthesis. This ATP is released from the mitochondrion, and broken down by the other organelles of the cell to power their own functions.[5]

DNA[change | change source]

It is thought that mitochondria were once independent bacteria, and became part of the eukaryotic cells by being engulfed, a process called endosymbiosis.[6]

Most of a cell's DNA is in the cell nucleus, but the mitochondrion has its own independent genome. Also, its DNA shows substantial similarity to bacterial genomes.[7]

The shorthand for mitochondrial DNA is either mDNA or mtDNA. Both have been used by researchers.

Inheritance[change | change source]

Mitochondria divides by binary fission similar to bacterial cell division. In single-celled eukaryotes, division of mitochondria is linked to cell division. This division must be controlled so that each daughter cell receives at least one mitochondrion. In other eukaryotes (in humans for example), mitochondria may replicate their DNA and divide in response to the energy needs of the cell, rather than in phase with the cell cycle.

An individual's mitochondrial genes are not inherited by the same mechanism as nuclear genes. The mitochondria, and therefore the mitochondrial DNA, usually comes from the egg only. The sperm's mitochondria enter the egg, but are marked for later destruction.[8] The egg cell contains relatively few mitochondria, but it is these mitochondria that survive and divide to populate the cells of the adult organism. Mitochondria are, therefore, in most cases inherited down the female line, known as maternal inheritance. This mode is true for all animals, and most other organisms. However, mitochondria is inherited paternally in some conifers, though not in pines or yews.[9]

A single mitochondrion can contain 2–10 copies of its DNA.[10] For this reason, mitochondrial DNA is thought to reproduce by binary fission, so producing exact copies. However, there is some evidence that animal mitochondria can undergo recombination.[11] If recombination does not occur, the whole mitochondrial DNA sequence represents a single haploid genome, which makes it useful for studying the evolutionary history of populations.

Population genetic studies[change | change source]

The near-absence of recombination in mitochondrial DNA makes it useful for population genetics and evolutionary biology.[12] If all the mitochondrial DNA is inherited as a single haploid unit, the relationships between mitochondrial DNA from different individuals can be seen as a gene tree. Patterns in these gene trees can be used to infer the evolutionary history of populations. The classic example of this is where the molecular clock can be used to give a date for the so-called mitochondrial Eve.[13][14] This is often interpreted as strong support for the spread of modern humans out of Africa.[15] Another human example is the sequencing of mitochondrial DNA from Neanderthal bones. The relatively large evolutionary distance between the mitochondrial DNA sequences of Neanderthals and living humans is evidence for a general lack of interbreeding between Neanderthals and anatomically modern humans.[16]

However, mitochondrial DNA only reflects the history of females in a population. It may not represent the history of the population as a whole. To some extent, paternal genetic sequences from the Y-chromosome can be used.[15] In a broader sense, only studies that also include nuclear DNA can provide a comprehensive evolutionary history of a population.[17]

Related pages[change | change source]

References[change | change source]

- ↑ single = 'mitochondrion'; from Greek mitos, a thread + khondrion, granule

- ↑ Henze K. & Martin W. 2003. Evolutionary biology: essence of mitochondria. Nature 426: 127–8.

- ↑ "The Powerhouse of the Cell". PBS LearningMedia. Retrieved 2017-12-03.

- ↑ McBride H.M; Neuspiel M. & Wasiak S. (2006). "Mitochondria: more than just a powerhouse". Curr. Biol. 16 (14): R551–R560. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2006.06.054. PMID 16860735. S2CID 16252290.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Campbell, Reece; et al. (2008). Biology: concepts and connections.

- ↑ Lake, James A. Evidence for an early prokaryote symbiogenesis. Nature 460 967–971.

- ↑ Andersson S.G.; et al. (2003). "On the origin of mitochondria: a genomics perspective". Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B, Biol. Sci. 358 (1429): 165–77, discussion 177–9. doi:10.1098/rstb.2002.1193. PMC 1693097. PMID 12594925.

- ↑ Sutovsky P.; et al. (1999). "Ubiquitin tag for sperm mitochondria". Nature. 402 (6760): 371–372. doi:10.1038/46466. PMID 10586873. S2CID 205054671. Discussed in Science News Archived 2007-12-19 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Mogensen H.L. (1996). "The hows and whys of cytoplasmic inheritance in seed plants". American Journal of Botany. 83 (3): 383–404. doi:10.2307/2446172. JSTOR 2446172.

- ↑ Wiesner R.J; Ruegg J.C. & Morano I. (1992). "Counting target molecules by exponential polymerase chain reaction, copy number of mitochondrial DNA in rat tissues". Biochim Biophys Acta. 183 (2): 553–559. doi:10.1016/0006-291x(92)90517-o. PMID 1550563.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Lunt D.B. & Hyman B.C. (15 May 1997). "Animal mitochondrial DNA recombination". Nature. 387 (6630): 247. Bibcode:1997Natur.387..247L. doi:10.1038/387247a0. PMID 9153388. S2CID 4318161.

- ↑ Castro J.A; Picornell A. & Ramon M. (1998). "Mitochondrial DNA: a tool for populational genetics studies". Int Microbiol. 1 (4): 327–32. PMID 10943382.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Cann R.L; Stoneking M. & Wilson A.C. (1987). "Mitochondrial DNA and human evolution". Nature. 325 (6099): 31–36. Bibcode:1987Natur.325...31C. doi:10.1038/325031a0. PMID 3025745. S2CID 4285418.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Torroni A; et al. (2006). "Harvesting the fruit of the human mtDNA tree". Trends Genet. 22 (6): 339–45. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2006.04.001. PMID 16678300.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Garrigan D. & Hammer M.F. (2006). "Reconstructing human origins in the genomic era". Nat. Rev. Genet. 7 (9): 669–80. doi:10.1038/nrg1941. PMID 16921345. S2CID 176541.

- ↑ Krings M.; et al. (1997). "Neandertal DNA sequences and the origin of modern humans". Cell. 90 (1): 19–30. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80310-4. PMID 9230299. S2CID 13581775.

- ↑ Harding R.M.; et al. (1997). "Archaic African and Asian lineages in the genetic ancestry of modern humans". Am J Hum Genet. 60 (4): 772–89. PMC 1712470. PMID 9106523.