Plate tectonics: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 31.25.3.99 (talk) to last version by Macdonald-ross |

Tectonic plate |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[File:Plates tect2 en.svg|thumb|250px|The tectonic plates of the world were mapped in the second half of the 20th century.]] |

[[File:Plates tect2 en.svg|thumb|250px|The tectonic plates of the world were mapped in the second half of the 20th century.]] |

||

[[Image:Tectonic plates Serret.png|thumb|300px|Tectonic plates (surfaces are preserved) [http://mappamundi.free.fr/pageF.php Mappamundi]]] |

|||

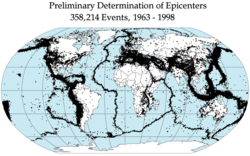

[[Image:Quake epicenters 1963-98.png|thumb|250px|Global earthquake [[epicenter]]s, 1963–1998]] |

[[Image:Quake epicenters 1963-98.png|thumb|250px|Global earthquake [[epicenter]]s, 1963–1998]] |

||

[[Image:Global plate motion 2008-04-17.jpg|thumb|250px|right|Global plate tectonic movement]] |

[[Image:Global plate motion 2008-04-17.jpg|thumb|250px|right|Global plate tectonic movement]] |

||

Revision as of 13:10, 19 February 2012

Plate tectonics [1] is a theory of geology. It has been developed to explain large scale motions of the Earth's lithosphere. This theory builds on older ideas of continental drift and seafloor spreading.[2][3]

Dissipation of heat from the mantle is the original source of energy driving plate tectonics. Exactly how this works is still a matter of debate. The driving forces of plate motion continue to be active subjects of on-going research.[4]

Earth's crust

The outermost part of the Earth's interior is made up of two layers. The lithosphere, above, includes the crust and the rigid uppermost part of the mantle.

Below the lithosphere is the asthenosphere. Although solid, the asthenosphere can flow like a liquid on long time scales. Large convection currents in the asthenosphere transfer heat to the surface, where plumes of less dense magma break apart the plates at the spreading centers. The deeper mantle below the asthenosphere is more rigid again. This is caused by extremely high pressure.

Thickness of plates

Ocean lithosphere varies in thickness. Because it is formed at mid-ocean ridges and spreads outwards, it gets thicker as it moves further away from the mid-ocean ridge. Typically, the thickness varies from about 6 kilometres (3.7 mi) thick at mid-ocean ridges to greater than 100 kilometres (62 mi) at subduction zones.[4]

Continental lithosphere is typically about 200 kilometres (120 mi) thick, though this also varies considerably between basins, mountain ranges, and stable cratonic interiors of continents. The two types of crust also differ in thickness, with continental crust being considerably thicker than oceanic (35 kilometres (22 mi) vs. 6 kilometres (3.7 mi)).[4]

Movement of plates

The lithosphere consists of tectonic plates. There are eight major and many minor plates. The lithospheric plates ride on the asthenosphere. These plates move at one of three types of plate boundaries.[5][6][7][8][9]

Earthquakes, volcanic activity, mountain-building, and oceanic trench formation occur along plate boundaries. The lateral movement of the plates varies from:

- 1–4 centimetres (0.39–1.57 in) per year (Mid-Atlantic Ridge). This is as fast as fingernails grow.

- 10 centimetres (3.9 in) per year (Nazca Plate). This is as fast as hair grows.[10][11]

Consequences

Tectonic plates can create mountains, earthquakes, volcanoes, mid-oceanic ridges and oceanic trenches, depending on which way the plates are moving.

- together = mountains; volcanoes. The Andes mountain range in South America and the Japanese island arc are examples. Also the Pacific Ring of Fire.

- away = earthquakes, trenches. The Mid-ocean ridges and Africa's Great Rift Valley are examples.

- side to side = earthquakes. The San Andreas Fault in California is an example of a transform boundary. New Zealand is another, more complex, example.

Major plates

Depending on how they are defined, there are usually seven or eight major plates:

- African Plate

- Antarctic Plate

- Indo-Australian Plate, sometimes subdivided into:

- Indian Plate

- Australian Plate

- Eurasian Plate

- North American Plate

- South American Plate

- Pacific Plate

Other pages

References

- ↑ from Greek τέκτων, tektōn "builder" or "mason"

- ↑ Oreskes, Naomi ed. 2003. Plate tectonics : an insider's history of the modern theory of the Earth. Westview Press ISBN 0-8133-4132-9

- ↑ Stanley, Steven M. 1999. Earth system history. Freeman. p211–228 ISBN 0-7167-2882-6

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Turcotte, D.L.; Schubert, G. (2002). "Plate Tectonics". Geodynamics (2 ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–21. ISBN 0-521-66186-2. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Turcotte-and-Schubert_2002" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Rolf Meissner 2002. The little book of planet Earth. New York: Copernicus Books. p202 ISBN 978-0-387-95258-1.

- ↑ "Plate Tectonics: Plate boundaries". platetectonics.com. Retrieved 12 June 2010.

- ↑ Tackley, Paul J. (2000-06-16). "Mantle convection and plate tectonics: towards an integrated physical and chemical theory". Science. 288 (5473): 2002–2007. doi:10.1126/science.288.5473.2002. PMID 10856206.

- ↑ Seyfert, Carl K. (1987). The Encyclopedia of Structural Geology and Plate Tectonics. ISBN 9780442281250.

- ↑ Oreskes (2003). Plate Tectonics : An Insider's History of the Modern Theory of the Earth. Westview Press. ISBN 9780813341329.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help); Unknown parameter|fisrt=ignored (help) - ↑ Huang Zhen Shao (1997). "Speed of the Continental Plates". The physics factbook.

- ↑ Hancock, Paul L; Skinner, Brian J; Dineley, David L (2000). The Oxford Companion to The Earth. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198540396.

- McKnight, Tom 2004. Geographica: The complete illustrated Atlas of the world, Barnes and Noble Books; New York ISBN 0-7607-5974-X

- Stanley, Steven M. 1999. Earth system history. Freeman. p211–228 ISBN 0-7167-2882-6

- Thompson, Graham R. and Turk, Jonathan 1991. Modern physical geology, Saunders. ISBN 0-03-025398-5

- Turcotte D.L. and Schubert G. 2002. Geodynamics 2nd ed, Wiley, New York. ISBN 0-521-66624-4

Other websites

- Movie showing 750 million years of global tectonic activity.

- More movies over smaller regions and smaller time scales.

- Easy-to-draw illustrations for teaching plate tectonics

- Map of tectonic plates

- MantlePlumes.org, the website that hosts the debate concerning whether deep mantle plumes exist or not

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link GA