Camera obscura

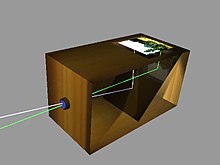

A camera obscura (plural camerae obscurae or camera obscuras, from Latin camera obscūra, "dark chamber")[1] is a darkened room with a small hole or lens at one side through which an image is projected onto a wall[2][3] or table[4] opposite the hole.[2][3] Camera obscura is Latin for "dark chamber."

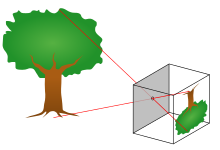

At its most basic, the camera obscura is a simple box (which may be room-sized) with a small hole in one side, (see pinhole camera for details on how to build one). Light from only one part of a scene will pass through the hole and strike a specific part of the back wall. (The projection can be made on paper on which an artist can copy the image.) As the pinhole is made smaller, the image gets sharper, but the light-sensitivity decreases. With this simple apparatus, the image is always upside-down. By using mirrors, as in the 18th century overhead version, it is also possible to project a "right-side-up" image.

Discovery and origins[change | change source]

The first mention and discovery of the principles behind the pinhole camera, a precursor to the camera obscura, belong to Mozi (470 BC to 390 BC), a Chinese philosopher and founder of Mohism. Later, Aristotle (384 to 322 BC) understood the optical principle of the pinhole camera. He viewed the crescent shape of a partially eclipsed sun projected on the ground through the holes in a sieve, and the gaps between leaves of a plane tree.

The first camera obscura was later built by an Iraqi scientist named Abu Ali Al-Hasan Ibn al-Haytham, born in Basra (965-1039 AD), known in the West as Alhacen or Alhazen, who carried out practical experiments on optics in his Book of Optics.[5][6]

In his various experiments, Ibn Al-Haitham used the term “al-Bayt al-Muẓlim”(Arabic: البيت المظلم), translated in English as dark room. In the experiment he undertook, in order to establish that light travels in time and with speed, he says: “If the hole was covered with a curtain and the curtain was taken off, the light traveling from the hole to the opposite wall will consume time.” He reiterated the same experience when he established that light travels in straight lines. The most revealing experiment which indeed introduced the camera obscura was in his studies of the half-moon shape of the sun’s image during eclipses which he observed on the wall opposite a small hole made in the window shutters. In his famous essay "On the form of the Eclipse" (Maqālah fī Sura al-Kosūf) (Arabic: مقالة في صورةالكسوف) he commented on his observation "The image of the sun at the time of the eclipse, unless it is total, demonstrates that when its light passes through a narrow, round hole and is cast on a plane opposite to the hole it takes on the form of a moon-sickle”.

In his experiment of the sun light he extended his observation of the penetration of light through the pinhole to conclude that when the sun light reaches and penetrates the hole it makes a conic shape at the points meeting at the pinhole, forming later another conic shape reverse to the first one on the opposite wall in the dark room. This happens when sun light diverges from point “ﺍ” until it reaches an aperture “ﺏﺤ” and is projected through it onto a screen at the luminous spot “ﺩﻫ”. Since the distance between the aperture and the screen is insignificant in comparison to the distance between the aperture and the sun, the divergence of sunlight after going through the aperture should be insignificant. In other words, “ﺏﺤ” should be about equal to “ﺩﻫ”. However, it is observed to be much greater “ﻙﻁ” when the paths of the rays which form the extremities of “ﻙﻁ” are retraced in the reverse direction, it is found that they meet at a point outside the aperture and then diverge again toward the sun as illustrated in figure 1. This was indeed the first accurate description of the Camera Obscura phenomenon.

In camera terms, the light converges into the room through the hole transmitting with it the object(s) facing it. The object will appear in full colour but upside down on the projecting screen/wall opposite the hole inside the dark room. The explanation is that light travels in a straight line and when some of the rays reflected from a bright subject pass through the small hole in thin material they do not scatter but cross and reform as an upside down image on a flat white surface held parallel to the hole. Ib Al-Haitham established that the smaller the hole is, the clearer the picture is.

Although both the pinhole camera and camera obscura is credited to Ibn al-Haytham,[7] the camera obscura was first described by Aristotle, who was the first to describe how an image is formed on the eye, using the camera obscura as an analogy. Alhazen states (in the Latin translation), and with respect to the camera obscura, "Et nos non inventimus ita", we did not invent this.[8]

Tourist attractions[change | change source]

Some camera obscura have been built as tourist attractions, often taking the form of a large chamber within a high building that can be darkened so that a 'live' panorama of the world outside is projected onto a horizontal surface through a rotating lens. Although few now survive, examples can be found at the following locations:

- Edinburgh in Scotland - See the Camera Obscura site

- Johannesburg in South Africa

- Pretoria in South Africa

- Cape Town in South Africa

- Lisbon and Tavira in Portugal

- Santa Monica in California

- Los Angeles at the Griffith Observatory

- San Francisco at the Cliff House

- North Carolina's "Cloud Chamber for the Trees and Sky"

- Havana in Cuba

- Royal Observatory, Greenwich, London

- Marburg, Germany

- Kentwell Hall, Suffolk

There is also a portable example which Willett & Patteson tour around England and the world.

Related pages[change | change source]

Notes[change | change source]

- ↑ "Introduction to the Camera Obscura". Science and Media Museum. 28 January 2011. Retrieved 6 March 2019.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Keener, Katherine (2020-03-02). "A Lesson on the Camera Obscura". Art Critique. Retrieved 2021-07-24.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Keats, Jonathon. "Prior To Demolition, These LACMA Galleries Took Selfies With A Little Help From The Pinhole Photographer Vera Lutter". Forbes. Retrieved 2021-07-24.

- ↑ "Table camera obscura, 19th century". SSPL Prints. Archived from the original on 2020-09-26. Retrieved 2021-07-24.

- ↑ Nicholas J. Wade, Stanley Finger (2001), "The eye as an optical instrument: from camera obscura to Helmholtz's perspective", Perception 30 (10), p. 1157–1177.

- ↑ "Construction of the First Camera Obscura : HistoryofInformation.com". www.historyofinformation.com.

- ↑ Wade, Finger.

- ↑ "Adventures in CyberSound: The Camera Obscura". Archived from the original on 2008-04-20. Retrieved 2008-03-07.

References[change | change source]

- Hill, D.R. (1993), ‘Islamic and Jewish Science and Engineering’, Edinburgh University Press, page 70.

Other websites[change | change source]

- An Appreciation of the Camera Obscura

- The Camera Obscura in San Francisco — The Giant Camera of San Francisco at Ocean Beach, added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2001

- Camera Obscura and World of Illusions, Edinburgh

- Dumfries Museum & Camera Obscura, Dumfries, Scotland Archived 2014-02-12 at the Wayback Machine

- Vermeer and the Camera Obscura by Philip Steadman

- Paleo-camera Archived 2014-07-06 at the Wayback Machine - The camera obscura and the origins of art

- Burns, Paul. The History of the Discovery of Cinematography Archived 2020-10-05 at the Wayback Machine An Illustrated Chronology

- Sinden Optical Company Archived 2006-10-04 at the Wayback Machine — Camera Obscura manufacturer.

- List of all known Camera Obscura Archived 2017-03-06 at the Wayback Machine

- Re-opened camera obscura on Eastbourne Pier, UK Archived 2007-03-11 at the Wayback Machine

- Willett & Patteson Camera Obscura hire and Creation.

- Camera Obscura and Outlook Tower, Edinburgh, Scotland Archived 2008-05-15 at the Wayback Machine

- Cameraobscuras.com George T Keene builds custom camera obscuras like the Griffith Observatory CO in Los Angeles.

- Camera obscura in Trondheim, Norway Archived 2011-06-15 at the Wayback Machine Built by students of architecture and engineering from NTNU (The Norwegian University of Science and Technology)

- Photo gallery and audio interview with Abelardo Morell, who creates room-size camera obscura images Archived 2007-02-04 at the Wayback Machine

- The Magic Mirror of Life - An Appreciation of the Camera Obscura

- Abelardo Morell[permanent dead link] Photographs displaying room size Camera Obscura images, by Abelardo Morell

- Making a Camera Obscura - BBC video clip from The Genius of Photography series 2007

- camera obscura - Research group at the University of Barcelona.

- www.estenopeica.es - Gabriel Lacomba: pinhole photography.

- kinor.net - Roland Buehlmann's abstract pinhole photography.