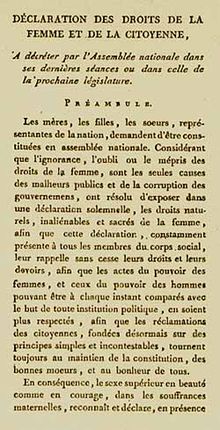

Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen

The Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen (French: Déclaration des droits de la femme et de la citoyenne) is a text written by Olympe de Gouges. De Gouges was a French activist, and playwright. She wrote it in response to the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, published in 1789. De Gouges wanted to show that the French Revolution had failed, because it did not recognize gender equality. The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen didn't apply to women. Because of her writings, de Gouges was accused, and tried. She was convicted of treason, and sentenced to death. She was soon executed on the Guillotine, together with other Girondists.

The text was published on 14 September 1791. It is also known as the Declaration of the Rights of Woman.

The Declaration of the Rights of Woman is important because it brought attention to ideas that would later be known as feminist concerns. Many people of hat time, recolutionaries and other people, had such ideas.

History[change | change source]

Previous attempts at equality[change | change source]

In 1789, the National Constituent Assembly adopted The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citize. This was at the time of the French Revolution. Marquis de Lafayette had prepared the text. The declaration said that that all men "are born and remain free and equal in rights" and that these rights were universal. The Declaration became a very important human rights document. It is a classic formulation of the rights of individuals toards the state.[1] The declaration showed inconsistencies of laws: These laws treated cirizens differently based on their sex,race, class, or religion.[2] In 1791, new articles were added to the French constitution. They extended civil and political rights to Protestants and Jews, who had previously been persecuted in France.[1]

In 1790, Nicolas de Condorcet and Etta Palm d'Aelders asked the National Assembly to extend civil and political rights to women.[2] They were not succesful.

In October 1789, women in the marketplaces of Paris, started a riot. The reason for that was there was only very little bread, and it was expensive. They marched to Versailles. This event is called the Women's March on Versailles today. The demostrators believed that equality among all French citizens would extend those rights to women, political minorities, and landless citizens.[3] After the march, the king acknowledged the changes of the French Revolution. The leaders of the Revolution did not recognize that women were the largest force in the march, and did not extend natural rights to women.[4][5]

In November 1789, a group of women submitted a petition for the extension of egalité to women. This was called Women's Petition to the National Assembly.

The group did this in response to the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. Another reason was that the National Assembly had failed to recognize the natural and political rights of women,

The French Revolution did not lead to a recognition of women's rights, and this prompted de Gouges to publish her Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen in early 1791.[6]

The politics of Gouges[change | change source]

Olympe de Gouges was a French playwright and political activist. Her feminist and abolitionist writings reached large audiences. She began her career as a playwright in the early 1780s, and as the political tensions of the French Revolution built, she became more involved in politics and law.

In 1788 she published Réflexions sur les hommes négres. This work demanded compassion for the plight of slaves in the French colonies.[7] For Gouges there was a direct link between the autocratic monarchy in France and the institution of slavery. She argued that "Men everywhere are equal… Kings who are just do not want slaves; they know that they have submissive subjects".[8] She came to the public's attention with the play l'Esclavage des Noirs, which was staged at the famous Comédie-Française in 1785.[9]

In 1791, King Louis XVI ratified the French Constitution. Shortly afterwards, Gouges wrote her famous Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen. She dedicated it to the King's wife, Queen Marie Antoinette. After the ratification, there was a constitutional monarchy in France. The constitution also madfe a status based citizenship. Citizens were defined as men over 25 who were "independent" and had paid the poll tax. These citizens had the right to vote. Active citizens were divided into two groups: those who could vote and those who were fit for public office. By definition, women did not have any of the rights of active citizenship. Like men who could not pay the poll tax, children, domestic servants, rural day-laborers, slaves, Jews, actors, and hangmen, women had no political rights. When it transferred sovereignty to the nation, the constitution dismantled the old regime. Gouges argued that it did not go far enough.[10] This was followed by her Contrat Social ("Social contract," named after a famous work of Jean-Jacques Rousseau). That work proposed marriage based upon gender equality.

The Declaration[change | change source]

The Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen was published on 15 September 1791.[11] It is modeled on the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen of 1789. Olympe de Gouges dedicated the text to Marie Antoinette, whom de Gouges described as "the most detested" of women. The Declaration states that "This revolution will only take effect when all women become fully aware of their deplorable condition, and of the rights they have lost in society".

The Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen follows the seventeen articles of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen point for point. Despite its serious intent, it has been described by one writer, Camille Naish, as "almost a parody... of the original document".[12]

Call to Action[change | change source]

De Gouges opens her Declaration with the famous quote, "Man, are you capable of being fair? A woman is asking: at least you will allow her that right. Tell me? What gave you the sovereign right to oppress my sex?" She demands that her reader observe nature and the rules of the animals surrounding them – in every other species, sexes coexist and [mix] peacefully and fairly. She asks why humans cannot act the same way. She demands that the National Assembly decree the Declaration a part of French law.[13] Also they have seen many wars in combat with the men of France therefore they sought out rights for themselves.

Reactions to the Declaration[change | change source]

After she had published her work, many of the radicals of the Revolution immediately suspected de Gouges of treason. When they saw that the the Declaration was dedicated to the queen, the Jacobins (led by Robespierre), suspected de Gouges (as well as her allies in the Girondists) of being Royalists. After de Gouges attempted to post a note demanding a plebiscite to decide between three forms of government (which included a Constitutional monarchy), the Jacobins quickly tried and convicted her of treason. She was sentenced to execution by the guillotine, and was one of many "political enemies" to the state of France claimed by the Reign of Terror.[6]

At the time of her death, the Parisian press no longer though she was harmless. While journalists and writers argued that her programs and plans for France had been irrational, they also noted that in proposing them she had wanted to be a "statesman." Her crime, the Feuille du Salut public reported, was that she had "forgotten the virtues which belonged to her sex." In the environment of Jacobin Paris, her feminism and "political meddlings" were seen as dangerous combination.[12]

De Gouges was a strict critic of the principle of equality, which was poular in Revolutionary France. According to her, it gave no attention to whom it left out. She worked to claim that it should also apply to women and slaves. She wrote many plays about the topics of black and women's rights and suffrage. The issues she brought up were spread not only through France, but also throughout Europe and the newly created United States of America.[12]

References[change | change source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Lauren, Paul Gordon (2003). The evolution of international human rights. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 18–20. ISBN 978-0-8122-1854-1.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Williams, Helen Maria; Neil Fraistat; Susan Sniader Lanser; David Brookshire (2001). Letters written in France. Broadview Press Ltd. p. 246. ISBN 978-1-55111-255-8.

- ↑ Lefebvre, Georges (1962). The French Revolution: From its Origins to 1793. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-7100-7181-7. OCLC 220957452.

- ↑ Lynn Avery Hunt, The challenge of the West: Peoples and cultures from 1560 to the global age, p. 672, D.C. Heath, 1995. [ISBN missing]

- ↑ "The Monstrous Regiment of Women: Revolutionary Women – The Women's March on Versailles". www.monstrousregimentofwomen.com. Retrieved 2015-12-16.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Naish, Camille (1991). Death comes to the maiden: Sex and Execution, 1431–1933. Routledge. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-415-05585-7.

- ↑ Erica Harth (1992). Cartesian Women: Versions and Subversions of Rational Discourse in the Old Regime. Cornell University Press. pp. 227. ISBN 978-0801499982.

- ↑ Erica Harth (1992). Cartesian Women: Versions and Subversions of Rational Discourse in the Old Regime. Cornell University Press. pp. 229. ISBN 978-0801499982.

- ↑ Lisa L. Moore; Joanna Brooks; Caroline Wigginton (2012). Transatlantic Feminisms in the Age of Revolutions. Oxford University Press. p. 245. ISBN 978-0199743483.

- ↑ Annie Smart (2011). Citoyennes: Women and the Ideal of Citizenship in Eighteenth-Century France. University of Delaware. p. 134. ISBN 978-1611493559.

- ↑ Célestin, R.; DalMolin, E.; Courtivron, I. (2016). Beyond French Feminisms: Debates on Women, Culture and Politics in France 1980–2001. Springer. pp. 44–45. ISBN 978-1-137-09514-5.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Naish, Camille (1991). Death comes to the maiden: Sex and Execution, 1431–1933. Routledge. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-415-05585-7.

- ↑ "Les Droits de la Femme – Olympe de Gouges". www.olympedegouges.eu. Archived from the original on 3 November 2021. Retrieved 2015-11-30.

Other websites[change | change source]

- The Rights of Women, by Olympe De Gouges, including the Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen, all in English Archived 3 November 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- History of women's right to vote – Official French website (in English)