Parsifal

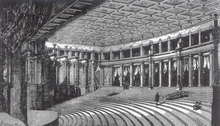

Parsifal is an opera in three acts by Richard Wagner. Wagner took most of the story from a medieval poem Parzival by the German poet Wolfram von Eschenbach. It was the last opera that Wagner completed. He started thinking about it in 1857 but did not do much work to it until after he had finished the cycle of four operas known as the Ring Cycle which was produced complete in 1876 in the special theatre (Festspielhaus) he had built in Bayreuth. Wagner composed his opera Parsifal so that it would suit the sound of this new theatre. It was first produced in 1882. The story is related to the Arthurian legends.

The Musical background to the opera

[change | change source]Wagner did more than any other composer in the 19th century to change the way that people listened to opera. In the 18th century people went to the opera house and sat in their boxes to chat to other people and be seen. Composers wrote operas with big arias which allowed the singers to show off their skills and make the audience applaud.

Wagner changed all this. He soon developed operas in which there is no difference between recitative (where the story is told) and arias (big songs for the soloists). The music of his later operas, especially Parsifal, is like a long, continuous line with rich, Romantic harmony. The music develops logically, with leitmotifs (very short pieces of music which represent particular people or ideas) which help the music and the story to develop.

The story of Parsifal

[change | change source]The story of Parsifal and the Holy Grail has survived in several forms that date from between 1170 and 1220. Wagner, who always wrote the words of his operas himself, used a mixture of several of these versions of the story to fit his ideas for the opera. Parsifal is a young man who is a “pure fool”, which means that he is an innocent, good man who slowly starts to understand the world. The Holy Grail is the cup from which Jesus Christ is supposed to have drunk at the Last Supper. The Holy Spear is the spear which is supposed to have been the one with which the Roman soldier pierced Jesus’ side when he was put on the cross. The Holy Grail and the Holy Spear are sacred relics (things from the past) which have been given to Titurel and his band of Christian knights to look after. Titurel has built a castle, Montsalvat, high up on the forest rocks, to guard them. In particular, he has to watch out for Klingsor who lives nearby. Klingsor is a magician who has a garden full of beautiful flower-maidens. These maidens are in his power. One of them is Kundry. She has already been made to lure several young knights to Klingsor’s power. Even Titurel’s son, Amfortas, could not resist the lure of Kundry. His spear was taken from him and he was badly wounded before being rescued. At the beginning of the opera he is lying in pain. The only thing that could heal the wound would be the touch of the Holy Spear which Klingsor now has, and the only person who could get that spear back again is a “pure fool”, a young man who knows nothing about the evil of the world and who can resist the beauty of the flower-maidens.

The story of the opera

[change | change source]Act I

[change | change source]

The opera starts with an orchestral prelude (Wagner does not call it an “overture”). When the curtain rises Gurnemanz, one of the senior knights, wakes up two sleeping servants. They kneel and pray as King Amfortas is brought down on his bed to the forest lake to bathe his wound. Kundry arrives, dashing in on her horse, looking for something to heal the wound (when Kundry is away from Klingsor she is not in his power. She feels that it was her fault that Amfortas was wounded. When Kundry is not in Klingsor’s power she is actually a faithful messenger of the Grail).

Suddenly a wounded swan (a bird that is sacred to the knights of the Grail) falls dead at Gurnemanz’s feet. The swan had been killed by Parsifal. He did not know that it was a wrong thing to do, but when the knights capture him he realizes his guilt and he breaks the arrow. The knights ask him his name, but Parsifal says he does not know his name or where he comes from. Suddenly the knights realize that Parsifal is the pure fool they need who can capture the Holy Spear.

The scene changes. The knights take communion. Amfortas is in terrible pain but has to do his duty in the ceremony. When the Holy Grail is shown it sparkles brightly in the hall. The knights sink to their knees. Only Parsifal does not seem to understand the meaning of it all.

Act II

[change | change source]

The scene is Klingsor’s magic garden by his castle. Kundry has been summoned by him is now quite different: she has no power of her own, and is controlled and tormented by Klingsor. Klingsor notices Parsifal, whom he is expecting, approach from the distance, and sends his magical knights to fight him, expecting them to be defeated by Parsifal. The flower-maidens, the wives of the knights, see Parsifal and call him by his name. No one has ever called him by his name before. When one of them kisses his lips he suddenly realizes what it is he has to do. He now remembers everything that has happened in Act I and understands its meaning. He throws the maiden to one side. Klingsor appears and throws the spear at Parsifal, but magically it stops over Parsifal’s head. Parsifal grabs it and makes the sign of the cross. The castle is destroyed, the gardens disappear, and he goes off back to the Grail.

Act III

[change | change source]

After a journey which takes him many years Parsifal comes back to the Grail forest. Gurnemanz is now very old. Kundry works for the knights. Parsifal himself is dressed as a black knight. Kundry recognizes him, but Gurnemanz does not. He is annoyed that an armed stranger should come on this holy day (it is Good Friday). Parsifal throws the spear into the ground, puts down his weapons and takes off his helmet. Gurnemanz realizes who it is. He helps him to dress like a knight of the Grail. Kundry washes his feet and dries them with her long hair. Gurnemanz blesses Parsifal’s head. Parsifal is now a knight of the Grail, and he baptizes Kundry. Titurel has just died, and Amfortas, still in terrible pain, comes out to uncover the Grail. Parsifal enters and touches the wound with the point of the spear. Amfortas’s pain changes to happiness, the shrine is opened, the Grail is surrounded by light. The knights kneel down, Kundry dies peacefully. All is forgiven. The music finishes with a climax based on the leitmotifs of the Holy Grail and the Sacrament.

The performances of Parsifal

[change | change source]

Until 1903, the Bayreuth Festspielhaus was the only place where Wagner’s opera Parsifal was allowed to be performed. In 1903, the opera was performed at the Metropolitan Opera in New York. Soon, it was being performed in other places as well.

Wagner like to describe Parsifal as "ein Bühnenweihfestspiel" ("A Festival Play for the Consecration of the Stage"). At Bayreuth, it has become tradition that there is to be no applause after the first act of the opera.

The conductor of the first performance was Hermann Levi, the court conductor at the Munich Opera. Wagner objected to Parsifal being conducted by a Jew (Levi's father was in fact a rabbi). Wagner first suggested that Levi should convert to Christianity, which Levi declined to do.[1] Wagner then wrote to King Ludwig that he had decided to accept Levi. This despite the fact that (he alleged) he had received complaints that "of all pieces, this most Christian of works" should be conducted by a Jew. The King expressed his satisfaction at this. He said that "human beings are basically all brothers". Wagner wrote to the King that he "regard[ed] the Jewish race as the born enemy of pure humanity and everything noble about it".[2]

References

[change | change source]- Footnotes

- Sources

- Ernest Newman (1976) The Life of Richard Wagner: 1813-1848. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521291491.

- John Deathridge (2008) Wagner Beyond Good and Evil. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520254534.