Set

A set is an idea from mathematics. A set has members (also called elements). A set is defined by its members, so any two sets with the same members are the same (e.g., if set and set have the same members, then ).

A set cannot have the same member more than once. Membership is the only thing that matters. For example, there is no order or other difference among the members. Anything can be a member of a set, including sets themselves (though if a set is a member of itself, paradoxes such as Russell's paradox can happen).

What to do with sets[change | change source]

Imagine the set is a bag.

Element of[change | change source]

Various things can be put into a bag. Later on, a good question would be if a certain thing is in the bag. Mathematicians call this element of. Something is an element of a set, if that thing can be found in the respective bag. The symbol used for this is :

,

which means that is in the bag or is an element of .

Unlike a bag, a set can contain at most one item of a given type. So for a set of fruits, it would make no difference if there is one orange, or if there are 10 oranges.

Empty set[change | change source]

Like a bag, a set can also be empty. The empty set is like an empty bag: it has nothing in it. The "empty set" is also called the null set and is represented by the symbol .[1]

Universe[change | change source]

If we consider, say, some sets of American cars, e.g. a set of all Fords and a set of all Dodges, we may also wish to consider the whole set of American cars. In this case, the set of all American cars would be called a universe.

In other words, a universe is a collection of all the elements one wishes to consider in a given problem. The universe is usually named .

Comparing sets[change | change source]

Two sets can be compared. This is like looking into two different bags. If they contain the same things, they are equal. No matter, in which order these things are.

For example, if and , the sets are the same.

Cardinality of a set[change | change source]

When mathematicians talk about a set, they sometimes want to know how big a set is (or what is the cardinality of the set). They do this by counting how many elements are in the set (how many items are in the bag). For finite sets the cardinality is a simple number. The empty set has a cardinality of 0. The set has a cardinality of 2.

Two sets have the same cardinality if we can pair up their elements—if we can join two elements, one from each set. The set and the set have the same cardinality. E.g., we could pair apple with sun, and orange with moon. The order does not matter. It is possible to pair all the elements, and none is left out. But the set and the set have different cardinality. If we try to pair them up, we always leave out one animal.

Infinite cardinality[change | change source]

At times cardinality is not a number. Sometimes a set has infinite cardinality. The set of all integers is a set with infinite cardinality. Some sets with infinite cardinality are bigger (have a bigger cardinality) than others. There are more real numbers than there are natural numbers, for example, which means we cannot pair up the set of integers and the set of real numbers, even if we worked forever.

Countability[change | change source]

If you can count the elements of a set, it is called a countable set. Countable sets include all sets with a finite number of members. Countable sets also include some infinite sets, such as the natural numbers. You can count the natural numbers with . The natural numbers are nicknamed "the counting numbers", since they are what we usually use to count things with.

An uncountable set is an infinite set that is impossible to count. If we try to count the elements, we will always skip some. It does not matter what step we take. The set of real numbers is an uncountable set. There are many other uncountable sets, even such a small interval like .[3]

Subsets[change | change source]

If you look at the set and the set , you can see that all elements in the first set are also in the second set.

We say: is a subset of

As a formula it looks like this:

In general, when all elements of set are also elements of set , we call a subset of :

.[1]

It is usually read " is contained in ."

Example: Every Chevrolet is an American car. So the set of all Chevrolets is contained in the set of all American cars.

Set operations[change | change source]

There are different ways to combine sets.

Intersections[change | change source]

The intersection of two sets and is a set that contains all the elements that are both in set and in set at the same time.

Example: When is the set of all cheap cars, and is the set of all American cars, then is the set of all cheap American cars.

Unions[change | change source]

The union of two sets and is a set that contains all the elements that are in set or in set . This "or" is the inclusive disjunction, so the union also contains the elements, that are in set and in set . By the way, this means, that the intersection is a subset of the union: .

Example: When is the set of all cheap cars, and is the set of all American cars, then is the set of all cars, without all expensive cars that are not from America.

Complements[change | change source]

Complement can mean two different things:

- The complement of is the universe without all the elements of :

The universe is the set of all things you speak about.

Example: When is the set of all cars, and is the set of all cheap cars,

then C is the set of all expensive cars.

- The set difference of and is the set without all the elements of :

It is also called the relative complement of in .

Example: When is the set of all cheap cars, and is the set of all American cars, then is the set of all expensive American cars.

If you exchange the sets in the set difference, the result is different:

In the example with the cars, the difference is the set of all cheap cars, that are not made in America.

Notation[change | change source]

Most mathematicians use uppercase ITALIC (usually Roman) letters to write about sets (such as , , ). The things that are seen as elements of sets are usually written with lowercase Roman letters.[1][2]

One way of showing a set is by a list of its members, separated by commas, included in braces. For example,

- is set which has members 1, 2, and 3.

Another way, called the set-builder notation,[3] is by a statement of what is true of the members of the set, like this:

- {x | x is a natural number & x < 4}.

In spoken English, this reads: "the set of all x such that x is a natural number and x is less than four". The symbol [ipe "|" means "such that" or "so that".

The empty set is written in a special way: , or .

When object a is the member of set it is written as:

- .

In spoken English, this reads: "a is a member of ".[1]

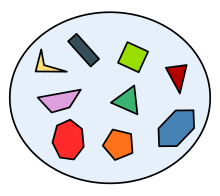

Venn diagrams[change | change source]

To illustrate operations on sets mathematicians use Venn diagrams. Venn diagrams use circles to show individual sets. The universe is depicted with a rectangle. Results of operations are shown as colored areas. In the illustration of the intersection operation the left circle shows set and the right circle shows set .

Special sets[change | change source]

Some sets are very important to mathematics. They are used very often. One of these is the empty set. Many of these special sets are written using blackboard bold typeface, and these include:[1][4]

- , denoting the set of all primes.

- , denoting the set of all natural numbers. That is to say, = {1, 2, 3, ...}, or sometimes = {0, 1, 2, 3, ...}.

- , denoting the set of all integers (whether positive, negative or zero). So = {..., -2, -1, 0, 1, 2, ...}.

- , denoting the set of all rational numbers (that is, the set of all proper and improper fractions). So, , meaning all fractions where a and b are in the set of all integers and b is not equal to 0. For example, and . All integers are in this set since every integer a can be expressed as the fraction .

- , denoting the set of all real numbers. This set includes all rational numbers, together with all irrational numbers (that is, numbers which cannot be rewritten as fractions, such as and √2).

- , denoting the set of all complex numbers.

Each of these sets of numbers has an infinite number of elements, and .

Paradoxes about sets[change | change source]

The mathematician Bertrand Russell found that there are problems with the informal definition of sets. He stated this in a paradox called Russell's paradox. An easier to understand version, closer to real life, is called the Barber paradox.

The barber paradox[change | change source]

There is a small town somewhere. In that town, there is a barber. All the men in the town do not like beards, so they either shave themselves, or they go to the barber shop to be shaved by the barber.

We can therefore make a statement about the barber himself: The barber shaves all men that do not shave themselves. He only shaves those men (since the others shave themselves and do not need a barber to give them a shave).

This of course raises the question: What does the barber do each morning to look clean-shaven? This is the paradox.

If the barber shaves himself, he cannot be a barber, since a barber does not shave himself. If he does not shave himself, he falls in the category of those who do not shave themselves, and so, cannot be a barber.

Related pages[change | change source]

References[change | change source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 "Comprehensive List of Set Theory Symbols". Math Vault. 2020-04-11. Retrieved 2020-08-19.

- ↑ "Introduction to Sets". www.mathsisfun.com. Retrieved 2020-08-19.

- ↑ Weisstein, Eric W. "Set". mathworld.wolfram.com. Retrieved 2020-08-19.

- ↑ "Set Symbols". www.mathsisfun.com. Retrieved 2020-08-19.

Further reading[change | change source]

The following books explore sets in more detail:

- Halmos, Paul R., Naive Set Theory, Princeton, N.J.: Van Nostrand (1960) ISBN 0-387-90092-6

- Stoll, Robert R., Set Theory and Logic, Mineola, N.Y.: Dover Publications (1979) ISBN 0-486-63829-4

- Allenby, R.B.J.T, Rings, Fields and Groups, Leeds, England: Butterworth Heinemann (1991) ISBN 0-340-54440-6

![{\displaystyle [0,1]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/738f7d23bb2d9642bab520020873cccbef49768d)