User:Captain-tucker/sandbox2

| Captain-tucker/sandbox2 |

|---|

Mount Washington is the highest peak in the Northeastern United States at 6,288 ft (1,917 m). It is famous for its dangerously erratic weather/ It holds the record for the highest wind gust directly measured at the Earth's surface, at 231 mph (372 km/h) on the afternoon of April 12, 1934. It was known as Agiocochook, or "home of the Great Spirit", before European settlers arrived.[4]

The mountain is located in the Presidential Range of the White Mountains, in Coos County, New Hampshire. It is the third highest state high point in the eastern U.S. and the most prominent peak in the Eastern United States.

While nearly the whole mountain is in the White Mountain National Forest, an area of 59 acres (0.24 km2) surrounding and including the summit is occupied by Mount Washington State Park.

History[change | change source]

The mountain was first reported by Giovanni da Verrazzano in 1524, from the Atlantic Ocean, as "high interior mountains". Darby Field claimed to have made the first ascent of Mt. Washington in 1642.[5] A geology party, headed by Dr. Cutler, named the mountain in 1784.[6] The Crawford Path, the oldest mountain hiking trail in America, was laid out in 1819 as a bridle path from Crawford Notch to the summit and has been in use ever since. Ethan Allen Crawford built a house on the summit in 1821, which lasted until a storm in 1826.[6]

Little activity occurred on the summit itself until the middle of the 19th century when it was developed as one of the first tourist destinations in the country, with the construction of more bridle paths and several summit hotels. The Summit House opened in 1852, burned in 1908 and was replaced in 1915. [6] The Tip Top House (1853), which is still standing, was recently renovated as a historical exhibit. Other tourist construction in the 19th century included a stagecoach road (1861)—now the Mount Washington Auto Road—and the Mount Washington Cog Railway (1869), both of which are still used. For forty years an intermittent daily newspaper, called Among The Clouds, was published by Henry M. Burt at the summit each summer, until 1917. Copies were circulated via the Cog Railway and coaches to surrounding hotels and other outlets.

Weather[change | change source]

Mount Washington has a subarctic climate[7], with the caveat that it receives an extremely high amount of precipitation, atypical for most regions with such cold weather.

The weather of Mount Washington is notoriously erratic. This is partly due to the convergence of several storm tracks, mainly from the South Atlantic, Gulf region and Pacific Northwest. The vertical rise of the Presidential Range, combined with its north-south orientation, makes it a significant barrier to westerly winds. Low-pressure systems are more favorable to develop along the coastline in the winter months due to the relative temperature differences between the Northeast and the Atlantic Ocean. With these factors combined, winds exceeding hurricane force occur an average of 110 days per year. From November to April, these strong winds are likely to occur during two-thirds of the days.

Mount Washington holds the world record for directly measured surface wind speed, at 231 mph (372 km/h), recorded on the afternoon of April 12, 1934. Phenomena measured via satellite or radar, such as tornadoes, hurricanes, and air currents in the upper atmosphere, are not directly measured at the Earth's surface and do not compete with this record.

The first regular meteorological observations on Mount Washington were conducted by the U.S. Signal Service, a precursor of the National Weather Service, from 1870 to 1892. The Mount Washington station was the first of its kind in the world, setting an example followed in many other countries. For many years, the record low temperature was thought to be −47 °F (−43.9 °C) occurring on January 29, 1934, but upon the first in-depth examination of the data from the 1800s at NOAA's National Climatic Data Center in Asheville, North Carolina, a new record low was discovered. Mount Washington's official record low of −50 °F (−45.6 °C) was recorded on January 22, 1885. However, there is also hand-written evidence to suggest that an unofficial low of −59 °F (−50.6 °C) occurred on January 5, 1871.

On January 16, 2004, the summit weather observation registered a temperature of −43.6 °F (−42.0 °C) and sustained winds of 87.5 mph (140.8 km/h), resulting in a wind chill value of −103 °F (−75.0 °C) at the mountain.[8] During a 71-hour stretch from around 3 p.m. on January 13 to around 2 p.m. on January 16, 2004, the wind chill on the summit never went above −50 °F (−46 °C).[8] Snowstorms at the summit are routine in every month of the year, with snowfall averaging 645 cm (21.2 ft) per year.

The primary summit building was designed to withstand 300 mph (480 km/h) winds; other structures are literally chained to the mountain. In addition to a number of broadcast towers, the mountain is the site of a non-profit scientific observatory reporting the weather as well as other aspects of the subarctic climate of the mountain. The extreme environment at the top of Mount Washington makes using unmanned equipment problematic. The observatory also conducts research, primarily the testing of new weather measurement devices. The Sherman Adams summit building, which houses the Observatory, is closed to the public during the winter and hikers are not allowed inside the building except for emergencies and pre-arranged guided tours.

The Mount Washington Observatory reoccupied the summit in 1932 through the enthusiasm of a group of individuals who recognized the value of a scientific facility at that demanding location. The Observatory's weather data have accumulated into a valuable climate record since. Temperature and humidity readings have been collected using a sling psychrometer, a simple device containing two mercury thermometers. Where most unstaffed weather stations have undergone technology upgrades, consistent use of the sling psychrometer has helped provide scientific precision to the Mount Washington climate record.

The Observatory makes prominent use of the slogan "Home of the World's Worst Weather", a claim that originated with a 1940 article by Charles Brooks (the man generally given the majority of credit for creating the Mount Washington Observatory), titled "The Worst Weather In the World" (even though the article concluded that Mt Washington most likely did not have the world's worst weather).[9][10]

Precipitation[change | change source]

Due to its high altitude, Mount Washington receives an extremely large quantity of precipitation, averaging an equivalent of 101.91 inches of rain per year, with a record high of 130.14 inches in 1969 and 71.34 inches in 1979. Large amounts of precipitation often fall in a short period of time. In October of 1996, a record 11.07 inches of precipitation fell during a single 24-hour period. A substantial amount of the precipitation falls as snow, with a yearly average of 314.8 inches of snow, and a record of 566.4 inches during the 1968-69 snow season. The record amount of snowfall in a 24-hour period occurred in February of 1969 and was 49.3 inches.[11]

Climate[change | change source]

| Climate data for Mt Washington | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Source: http://www.climate-zone.com/climate/united-states/new-hampshire/mt-washington/index_centigrade.htm | |||||||||||||

Geographical features[change | change source]

Although the western slope that the Cog Railway ascends is straightforward from base to summit, the mountain's other sides are more complex. On the north side, Great Gulf—the mountain's largest glacial cirque—forms an amphitheater surrounded by the Northern Presidentials: Mounts Clay, Jefferson, Adams and Madison. These connected peaks reach well into the treeless alpine zone. Massive Chandler Ridge extends northeast from the summit of Washington to form the amphitheater's southern wall and is the incline ascended by the automobile road.

East of the summit, a plateau known as the Alpine Gardens extends south from Chandler Ridge at about 5,200 feet (1,600 m) elevation. It is notable for plant species either endemic to alpine meadows in the White Mountains or outliers of larger populations in arctic regions far to the north. Alpine Gardens drops off precipitously into two prominent glacial cirques. Craggy Huntington Ravine offers rock and ice climbing in an alpine setting. More rounded Tuckerman Ravine is New England's premier venue for spring skiing as late as June and then a scenic hiking route.

South of the summit lies a second and larger alpine plateau, Bigelow Lawn, at 5,000 feet (1,500 m) to 5,500 feet (1,700 m) elevation. Satellite summit Boott Spur and then the Montalban Ridge including Mount Isolation and Mount Davis extend south from it, while the higher Southern Presidentials—Mounts Monroe, Franklin, Eisenhower, Pierce, Jackson and Webster—extend southwest to Crawford Notch. Oakes Gulf separates the two high ridges.

Uses[change | change source]

The mountain is part of a popular hiking area, with the Appalachian Trail crossing the summit and one of the Appalachian Mountain Club's eight mountain huts, the Lakes of the Clouds Hut, located on one of the mountain's shoulders. Winter recreation includes Tuckerman Ravine, famous for its Memorial Day skiing and its 45-degree slopes. The ravine is notorious for its avalanches, of which about 100 are recorded every year, and which have killed six people since 1849.[12] Scores of hikers have died on the mountain in all seasons, due to inadequate equipment, failing to plan for the wide variety of conditions which can occur above tree line, and poor decisions once the weather began to turn dangerous.[13]

The weather at Mount Washington has made it a popular site for glider flying. In 2005, it was recognized as the 14th National Landmark of Soaring.[14]

Hiking[change | change source]

The most popular hiking trail approach to the summit is via the 4.2-mile (6.8 km) Tuckerman Ravine Trail. It starts at the Pinkham Notch camp area and gains 4,280 feet (1,300 m), leading straight up the bowl of Tuckerman Ravine via a series of steep rock steps which afford spectacular views of the ravine and across the notch to Wildcat Mountain. Fatalities have occurred on the trail, both from ski accidents and hypothermia. Water bottles may be refilled at the base of the bowl 2.1 miles (3.4 km) up the trail at a well pump near a small hiker's store which offers snacks, toilets and shelter. At the summit is a center with a museum, gift shop, observation area, and cafeteria. Descent, if not by foot, can be made by shuttle bus back to the Pinkham Notch camp for a fee. Other routes up the mountain include the Ammonoosuc Ravine Trail and the Jewell Trail.

Cog Railway[change | change source]

Since 1869, the Mount Washington Cog Railway has provided tourists with a train journey to the summit of Mount Washington. It uses a Marsh rack system and was the first successful rack railway in the US.

A tradition of thru-hikers Mooning the Cog has developed on Mount Washington as the trail and railroad intersect near the summit of the mountain.[15][16]

Races[change | change source]

Every year in June, the mountain is host to the Mount Washington Road Race, an event which attracts hundreds of runners. In July the mountain is the site of Newton's Revenge and in August the Mount Washington Auto Road Bicycle Hillclimb, both of which are bicycle races that run the same route as the road race. The hillclimb's most notable victor to date has been former Tour de France contender Tyler Hamilton.

Another event, although not a race, is the annual MINIs On Top event. The drive to the summit began with 73 MINI Cooper and Cooper S vehicles and now exceeds 200 cars. MINIs On Top (or MOT) is held the Saturday of Father's Day weekend every June. The Mt. Washington Auto Road has also hosted the Mt. Washington Alternative Energy Days, a two-day gathering of alternative energy alternative vehicles.

On August 7, 1932, Raymond E. Welch, Sr., became the first one-legged man to climb Mount Washington. An official race was held and open only to one-legged people. Mr. Welch climbed the "Jacob's Ladder" route and descended via the carriage road. Raymond Welch had lost his leg due to a sledding injury as a seven year old child. This climb was recognized by the Boston Globe, Manchester Union, and Plymouth Record newspapers. At the time of his climb, Mr. Welch was the station agent for the Boston & Maine Railroad in Northumberland, New Hampshire.

Transmitting stations[change | change source]

Edwin H. Armstrong installed an FM-broadcasting station on the top of Mount Washington in 1937. The station stopped operating in 1948, due to excessive maintenance costs. In 1954 a TV tower and transmitters were installed for WMTW, Channel 8, licensed to Poland Spring, Maine. The station continuously broadcast from the top of the mountain, including local forecasts by (now retired) WMTW transmitter engineer Marty Engstrom.[17] WMTW continually broadcast from the mountaintop until 2002.

Mount Washington continued FM broadcasting in 1958 with the construction of WHOM 94.9, which was then WWMT. WHOM and WMTW-TV both shared a transmitter building, which also housed the generators to supply power to the mountain. On February 9, 2003, a fire[18] destroyed the transmitter building and the generators (where it started), which at the time still had WHOM's transmitters inside it. WHOM subsequently built a new transmitter building on the site of the old power building, and also constructed a new standby antenna on the Armstrong tower. (For the first time since 1948, the Armstrong tower was used for broadcasts.)

In 1987, WHOM and WMTW where joined on the peak of the mountain by WMOU-FM (now WPKQ) on a separate tower. The WPKQ transmitters are located in the back of the Yankee Building. Due to the extreme weather on Mount Washington, both WHOM and WPKQ use specially designed FM antennas which are housed in special cylindrical radomes, manufactured by Shively Labs of nearby Bridgton, Maine.

In June 2008, the possibility of television returning to Mount Washington came to the light, with the filing by New Hampshire Public Television to move WLED-TV from its current location near Littleton to the old WMTW mast on top.[19][20]

Artistic tributes[change | change source]

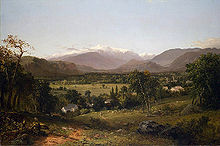

Mount Washington from the Valley of Conway

Mount Washington has been the subject of several famous New England paintings, dating from the French and Indian wars. During the late 1700s and early 1800s an artist colony in Conway generated a flood of landscape paintings that have found their way across the world, most notably in Hampton Court. Musical tributes have also been made, such as Symphony no. 64, Op. 422 ("Agiochook"), composed around 1990 by the American composer Alan Hovhaness (1911–2000), dedicated to Mount Washington, which the composer climbed during his youth.

See also[change | change source]

- List of U.S. states by elevation

- Mountain peaks of North America

- Mountain peaks of the United States

- Pinkham Notch

Notes[change | change source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Mount Washington". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. 1980-07-27. Retrieved 2008-11-28.

- ↑ "Mount Washington". NGS data sheet. U.S. National Geodetic Survey. Retrieved 2009-02-23.

- ↑ "America's 57 - The Ultras". Peaklist - Prominence of Mountains of the World. Retrieved 2008-08-30.

- ↑ "Dartmouth College Library Collections". Proquest.com. Retrieved 2008-03-08.

- ↑ USGW Archives C. Norris & Co. , Exeter, NH, ©1817 (1817). "Gazetteer of the State of New Hampshire 1817". Retrieved 2008-08-24.

{{cite web}}: External link in|author= - ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Condensed Facts About Mount Washington, Atkinson News Co., 1912.

- ↑ Mount Washington Observatory: Distance Learning, Retrieved Jul. 1, 2009.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "History for Mt. Washington, NH". Weather Underground. Retrieved 2008-03-08.

- ↑ Allen Press "The Mount Washington Weather Observatory - 50 Years Old"

- ↑ "The Worst Weather In the World"

- ↑ Mount Washington Observatory: Normals, Means, and Extremes, Retrieved Jul. 1, 2009.

- ↑ MountWashington.com - Deaths

- ↑ ibid.

- ↑ "Mount Washington National Landmark of Soaring". Mount Washington Soaring Association, chapter of Soaring Society of America. Retrieved 2008-10-08.

- ↑ Patricia Pelosi (2007-11-15). "Officials Charge Hikers Who Moon Cog Railway". WLBZ, Bangor. Retrieved 2008-03-08.

- ↑ Katie Zezima (2007-11-23). ""Riding the Rail to the Top, and Not Amused"". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-03-08.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ↑ Marty Engstrom. Marty on the Mountain: 38 Years on Mt. Washington. Retrieved 2008-10-13.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - ↑ "WMTW: fire on the mountain". GGN Information Systems. Retrieved 2008-10-13.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - ↑ "Application for Construction Permit for Reserved Channel Noncommercial Educational Broadcast Station". U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC). June 20, 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-13.

- ↑ ""Mount Washington, N.H.: A Look Back"". fybush.com. 2003-02-20. Retrieved 2008-03-08.