User:Student Eilasor

Leiden University, History of the Modern Middle East, 2021-22

I am a student enrolled in the course above, whose assessment entails editing a Simple Wikipedia entry. I will be using the space below to draft this entry.

The First Ottoman Constitution[change | change source]

Several young Armenians who had travelled back to the Ottoman Empire after receiving higher education in Western Europe saw several problems with the millet system when they returned home. The leaders of the Armenian millet were corrupt and wanted to cooperate with Ottoman powers and keep the people in their millet in ignorance.[1] This group of intellectuals wanted written regulations defining the duties of the people at the top of the Armenian millet, such as the patriach. Reogranising the millet would help separate state and religion.[2] After several rejections a Code of Regulations was accepted by the National Assembly in 1860. This code was 150 articles long and among other things reduced the power of the Armenian partiarch, but he was still the representative of the Armenian millet. The document was called the Armenian National Constitution, but it was only valid for inside the Armenian millet, which is why, according to scholars, Code of Regulations is a more fitting term .[3]

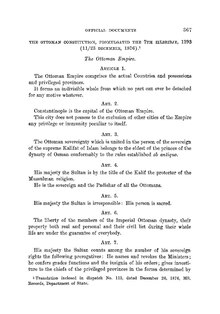

The Armenian National Constitution did not change much for the people in the millet, but it is one of the factors which led to the making of the First Ottoman Constitution in 1876.[1][2] The first Ottoman Constitution was created by Midhat Pasha in order to calm the chaos in the Ottoman Empire and decrease the power of seperatist movements. This new Ottoman Constitution set the path for the Ottoman Empire for modernization and becoming more like the West.[4] The period in which this constitution was implemented is called the First Constitutional Period and took from 1876-1878.[5]

The Armenian National Constitution is still used in the Armenian Church in the diaspora. [3]

The First Ottoman Constitution was implemented again in 1908 after the Young turk Revolution.[5]

The Armenian Genocide[change | change source]

The Armenians in the Ottoman Empire have been subject to several massacres before 1915, such as the Adana massacres in 1909 and the Hamidian massacres in 1894-1896.[6] While the former massacres were often to scare and intimidate the Armenians, the genocide in 1915 had as goal to completely eliminate the Armenians from the Ottoman Empire. The Armenian Genocide is the name for the deportation and killing of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire, which ended in the death of 80,000 to 1,5 million Armenian people.[7]

In 1913, the year before the genocide, around 2 million Armenians were living in the Ottoman Empire.[8] At the start of World War I the Ottoman Empire was fighting with the Russians, as well as the British and French at the same time. The losses of the Balkan War included more than half of the European territory that used to be part of the Ottoman Empire. The Ottoman government decided that it was not possible for the Muslim Ottomans to live alongside the Christian population of the Ottoman Empire and wanted to homogenize the population.[6] The Committee of union and Progress (CUP) was the governing party of the Ottoman Empire from 1908 to 1918.[9] The CUP was a nationalist party who believed in Ottomanism and saw the need for the Turks as a dominant group.[6] This included relocating the non-Turk Muslim population and the non-Muslim population of the Ottoman Empire.

The Russians took advantage of the fact that the Ottoman Empire was fighting a war at two fronts and moved their army towards the city in Eastern Anatolia with the largest Armenian population. The Armenians did not agree wether to support the Russians or the Ottomans, some joined the Russian army, others the Ottoman army and others did not join. The deportation of Armenians from towns most affected by the fighting was ordered by the Ottoman government, this later included all Armenians in Anatolia. The orders were carried out by Ottoman officials, as well as Turks, Kurds and local tribespeople. Many Armenians died in these deportations, many fled to Syria, Russia or Iraq and many died while fleeing. The Armenians who were being deported were ofted raped, kidnapped or starved. Around 800,000 to 1.5 million Armenians died during these massacres, the people who remained in the Ottoman Empire were often women and girls who were forced to marry into Turkish Muslim families. The boys were often adopted and converted to Islam.[9][10]

Not everybody has agreed on the reason or a name for the events that happened to the Armenians in 1915 and during World War I. The Turkish government calls these deportations a defensive action against rebellion, started by Kurds and local Muslim rebels, while the Armenian people call it a genocide.[9] It is a genocide according to the definition of genocide by the United Nations.[11]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "IV. Reorganization of the Non-Muslim Millets, 1860-1865", Reform in the Ottoman Empire, 1856-1876, Princeton University Press, pp. 114–135, 1964-12-31, doi:10.1515/9781400878765-006, ISBN 978-1-4008-7876-5, retrieved 2022-05-12

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Davison, Roderic H. (1963). Reform in the Ottoman Empire, 1856-1876. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-7876-5. OCLC 966765216.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Hovannisian, Richard G. (1996). The Armenian People from Ancient to Modern Times: Volume 2. Foreign Dominion to Statehood: The Fifteenth Century to the Twentieth Century. Basingstoke: Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-61974-9. OCLC 59862523.

- ↑ "X. The Constitution of 1876", Reform in the Ottoman Empire, 1856-1876, Princeton University Press, pp. 358–408, 1964-12-31, doi:10.1515/9781400878765-012, ISBN 978-1-4008-7876-5, retrieved 2022-05-12

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Kayali, Hasan (1995). "Elections and the Electoral Process in the Ottoman Empire, 1876–1919". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 27 (3): 265–286. doi:10.1017/s0020743800062085. ISSN 0020-7438.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Akçam,, Taner, (2006). A shameful act : the Armenian genocide and the question of Turkish responsibility / by Taner Akçam ; translated by Paul Bessemer, with Julie Gilmour. ISBN 978-0-8050-8665-2. OCLC 1298731670.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Göçek, Fatma Müge,. Denial of violence : Ottoman past, Turkish present and collective violence against the Armenians, 1789-2009. ISBN 978-0-19-062458-3. OCLC 965118273.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ De Waal, Thomas (2015). Great catastrophe : Armenians and Turks in the shadow of genocide. Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-935070-4. OCLC 897378977.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Anderson, Betty S. (2016). A history of the modern Middle East : rulers, rebels, and rogues. Stanford, California. ISBN 978-0-8047-9875-4. OCLC 945376555.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Donald., Bloxham, (2009). The great game of genocide : imperialism, nationalism and the destruction of the Ottoman Armenians. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-922688-7. OCLC 1084543176.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Nations, United. "United Nations Office on Genocide Prevention and the Responsibility to Protect". www.un.org. Retrieved 2022-05-11.