1788–89 United States presidential election

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

69 members of the Electoral College 35 electoral votes needed to win | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turnout | 11.6%[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Presidential election results map. Green shows states that Washington won. Black states are states that didn't vote. The numbers in each state shows the number of votes given by each state.[note 1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

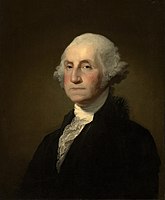

The 1788–89 United States presidential election was the first presidential election in the United States. It happened from Monday, December 15, 1788, to Saturday, January 10, 1789, under the new Constitution made official that same year. George Washington was elected with no opposition. This would be the first of two times he was elected, as he would serve two terms as president. John Adams became the first vice president. This was the only U.S. presidential election that took more than one calendar year (not counting ones that had a follow-up election). It was also the first national presidential election in America.

Under the Articles of Confederation, which were created in 1781, the United States had no head of state. The executive function of government remained with the legislative similar to countries that use a parliamentary system. Federal power, which wasn't as powerful, was only managed by the Congress of the Confederation whose "President of the United States in Congress Assembled" was also chair of the Committee of the States which existed to do a job similar to that of the modern Cabinet.

The Constitution created the offices of President and Vice President, and separated their jobs from Congress. The Constitution made an Electoral College, based on each state's number of Congressmen, where each elector would make two votes for two candidates, a process changed in 1804 by the passing of the Twelfth Amendment. States had different ways for choosing presidential electors.[2] In five states, the state government chose electors. The other six chose electors through, in some way, having the people vote. However, only two states had the population vote directly.

Washington, who was really popular, was well known as the past Commander of the Continental Army during the American Revolution. After he agreed to come out of retirement, he was easily elected by everyone. Because the vice president used to also be elected through the electoral college, Washington didn't choose one.

No political parties existed. However, most people called themselves Federalists or Anti-Federalists. Because of this, the contest for the Vice-President was anyone's game. Thomas Jefferson predicted that a popular leader from the North like John Hancock from Massachusetts or John Adams, a past American representative to Great Britain who had represented Massachusetts in Congress, would be elected vice president. Anti-Federalist leaders such as Patrick Henry, who didn't run, and George Clinton, who didn't like the Constitution, were also choices.

The entire electoral college, which had 69 people, made one vote for Washington, making his election an unopposed win. Adams won 34 votes and became vice president. The other 35 votes went to ten different people, like John Jay, who finished third with nine. Three states couldn't be in the election: New York's state government chose their electors too late and North Carolina and Rhode Island had not recognized the constitution yet. Washington was inaugurated in New York City on April 30, 1789, 57 days after the First Congress first met.

Candidates[change | change source]

Even though no political parties existed yet, people's opinions were a bit divided between those who had liked ratification (creation) of the Constitution, called Federalists also known as Cosmopolitans, and Anti-Federalists or Localists who either weren't sure about ratification or didn't like it at all. However, everyone supported Washington for President. Some campaining happened in divided places. For example, in Maryland, a state that let people vote, unofficial parties campaigned.

Federalist candidates[change | change source]

Anti-Federalist candidates[change | change source]

General election[change | change source]

Since no political parties existed, no process to decide Federalist and Anti-Federalist candidates existed at the time, and that caused most to expect Washington to win easily. For example, Alexander Hamilton agreed with the public's opinion when he wrote a letter to Washington attempting to persuade him to leave retirement on his farm in Mount Vernon to serve as President. He wrote that "...the point of light in which you stand at home and abroad will make an infinite difference in the respectability in which the government will begin its operations in the alternative of your being or not being the head of state."

Another thing people weren't sure of was who would be the candidate for the vice presidency, which didn't have a real description except being next in line to the presidency and watching over the Senate. The Constitution said that the job would be given to the second place person in the Presidential election. Since Washington was from Virginia, the largest state, many thought electors would choose a vice president from a different state, likely in the north. In a letter written in August 1788 , U.S. Minister to France Thomas Jefferson wrote that he thought John Adams and John Hancock, both from Massachusetts, would be the top people for vice president. Jefferson recommended John Jay, John Rutledge, and a candidate from Virginia, James Madison, as other possible winners.[3] Adams received 34 votes, one short of a majority (over half). Since the Constitution didn't require a majority in the Electoral College before the creation of the Twelfth Amendment in 1804, Adams was elected.

The popular vote count was a low single-digit percentage of the adult population. Even though all states allowed some form of popular vote, only six states allowed any form of popular vote for presidential electors. In most states only white men, and in many only those who owned property, could vote. Free black men could vote in four Northern states, and women could vote in New Jersey until 1776. In some states, there was a religious test for voting. For example, in Massachusetts and Connecticut, the Congregational Church was made, supported by taxes. Voting was delayed a lot by bad communications and the heavy amount of work by farming. Two months passed after the election before the votes were counted and Washington was told he had been elected president. Washington took eight days to travel from Virginia to New York for the inauguration.[4] Congress took twenty-eight days to assemble.[5]

As the electors were selected, politics got in the way, and the process had many rumors and speculation. For example, Hamilton tried to ensure that Adams did not accidentally tie Washington in the electoral vote.[6] Also, Federalists spread rumors that Anti-Federalists wanted to elect Richard Henry Lee or Patrick Henry president, with George Clinton as vice president. However, Clinton received only three votes.[7]

Results[change | change source]

Popular vote[change | change source]

| Popular vote(a), (b), (c) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Count | Percentage | |

| Federalist electors | 39,624 | 90.5% |

| Anti-Federalist electors | 4,158 | 9.5% |

| Total | 43,782 | 100.0% |

Source: United States Presidential Elections, 1788-1860: The Official Results by Michael J. Dubin[8]

(a) Only six of the 11 states that were able to cast electoral votes chose electors by any type of popular vote.

(b) Less than 1.8% of the population voted: the 1790 Census would count a total population of 3.0 million with a free population of 2.4 million and 600,000 slaves in those states making electoral votes.

(c) States that did choose electors by popular vote had different restrictions on voting depending on rpoperty requirements.

Electoral vote[change | change source]

| Presidential candidate | Party | Home state | Popular vote(a), (b), (c) | Electoral vote(d), (e), (f) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Percentage | ||||

| George Washington | Independent | Virginia | 43,782 | 100.00% | 69 |

| John Adams | Federalist | Massachusetts | — | — | 34 |

| John Jay | Federalist | New York | — | — | 9 |

| Robert H. Harrison | Federalist | Maryland | — | — | 6 |

| John Rutledge | Federalist | South Carolina | — | — | 6 |

| John Hancock | Federalist | Massachusetts | — | — | 4 |

| George Clinton | Anti-Federalist | New York | — | — | 3 |

| Samuel Huntington | Federalist | Connecticut | — | — | 2 |

| John Milton | Federalist | Georgia | — | — | 2 |

| James Armstrong(g) | Federalist | Georgia(g) | — | — | 1 |

| Benjamin Lincoln | Federalist | Massachusetts | — | — | 1 |

| Edward Telfair | Federalist[9] | Georgia | — | — | 1 |

| Total | 43,782 | 100.0% | 138 | ||

| Needed to win | 35 | ||||

Source: Template:National Archives EV source Source (popular vote): A New Nation Votes: American Election Returns 1787–1825[10]

(a) Only 6 of the 10 states making electoral votes chose electors by any type of popular vote.

(b) Less than 1.8% of the population voted: the 1790 Census would count a total population of 3.0 million with a free population of 2.4 million and 600,000 slaves in those states making electoral votes.

(c) States that did choose electors by popular vote had different restrictions on suffrage depending property requirements.

(d) Because the New York government elected electors too late, there were no voting electors from New York.

(e) Two electors from Maryland didn't vote.

(f) One elector from Virginia didn't vote and another elector from Virginia was not chosen because an election region failed to submit forms.

(g) The identity of this person comes from The Documentary History of the First Federal Elections (Gordon DenBoer (ed.), University of Wisconsin Press, 1984, p. 441). Several respected sources, including the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress and the Political Graveyard, instead show this person to be James Armstrong of Pennsylvania. However, primary sources, such as the Senate Journal, list only Armstrong's name, not his state. People who question it say that Armstrong received his single vote from an elector from Georgia. They find this impossible because Armstrong was not nationally known, as his public service to that date made up of being a medical officer during the American Revolution and, at most, one year as a Pennsylvania judge.

Results by state[change | change source]

Popular vote[change | change source]

The popular vote totals used are the elector from each party with the highest votes. The vote totals of Virginia are apparently incomplete.

| Federalist electors | Anti-Federalist electors | Margin | Not cast | Citation | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | Electoral votes |

# | % | Electoral votes |

# | % | Electoral votes |

# | % | ||||

| Connecticut | 7 | No popular vote | 7 | No popular vote | - | - | - | - | |||||

| Delaware | 3 | 522 | 100.00 | 3 | No ballots | - | 522 | 100.00 | - | [11] | |||

| Georgia | 5 | No popular vote | 5 | No popular vote | - | - | - | - | |||||

| Maryland | 6 (8) | 11,342 | 71.65 | 6 | 4,487 | 28.35 | - | 6,855 | 43.3 | 2 | [12] | ||

| Massachusetts | 10 | 3,748 | 96.60 | 10 | 132 | 3.40 | - | 3,616 | 93.20 | - | [13] | ||

| New Hampshire | 5 | 1,759 | 100.00 | 5 | No ballots | - | 1,759 | 100.00 | - | [14] | |||

| New Jersey | 6 | No popular vote | 6 | No popular vote | - | - | - | - | |||||

| New York | 0 (8) | Legislature did not choose electors on time | - | - | - | ||||||||

| North Carolina | 0 (7) | Had not yet ratified Constitution | - | - | - | ||||||||

| Pennsylvania | 10 | 6,711 | 90.90 | 10 | 672 | 9.10 | - | 6,039 | 81.80 | - | [15] | ||

| Rhode Island | 0 (3) | Had not yet ratified Constitution | - | - | - | ||||||||

| South Carolina | 7 | No popular vote | 7 | No popular vote | - | - | - | - | |||||

| Virginia | 10 (12) | 668 | 100.00 | 10 | No ballots | - | 668 | 100.00 | 2 | [16] | |||

| TOTALS: | 69 (91) | 24,750 | 82.39 | 69 | 5,291 | 17.61 | 0 | 19,459 | 64.78 | 4 | |||

| TO WIN: | 35 (46) | ||||||||||||

Electoral vote[change | change source]

Sixty-nine electors voted out of a possible 91: Two electors from Maryland and two from Virginia did not vote, the New York government was divided and the state's 8 electors were not appointed (see below), and North Carolina with 7 votes and Rhode Island with 3 votes hadn't recognized the Constitution. As the Constitution before 1804 says, each elector was allowed to make two votes for president, with a majority of "the whole number of electors appointed" (the total amount of voters) needed to elect a president. Out of the 69 electors, everyone voted for Washington who became president. Of the other candidates, only Adams, Jay, and Hancock received votes from more than one state. With 34 votes, Adams finished second behind just Washington, and because of that he was elected vice president.

| State | Electors | Electoral votes |

GW | JAd | JJ | RH | JR | JH | GC | SH | JM | JAr | BL | ET | Blank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Connecticut | 7 | 14 | 7 | 5 | — | — | — | — | — | 2 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Delaware | 3 | 6 | 3 | — | 3 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Georgia | 5 | 10 | 5 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | — |

| Maryland | 8 | 16 | 6 | — | — | 6 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 4 |

| Massachusetts | 10 | 20 | 10 | 10 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| New Hampshire | 5 | 10 | 5 | 5 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| New Jersey | 6 | 12 | 6 | 1 | 5 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| New York | 8 | 16 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 16 |

| Pennsylvania | 10 | 20 | 10 | 8 | — | — | — | 2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| South Carolina | 7 | 14 | 7 | — | — | — | 6 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Virginia | 12 | 24 | 10 | 5 | 1 | — | — | 1 | 3 | — | — | — | — | — | 4 |

| TOTAL | 81 | 162 | 69 | 34 | 9 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 24 |

| TO WIN | 37 | 37 | |||||||||||||

Source: "The Electoral College Count for the Presidential Election of 1789". Washington Papers. University of Virginia. Retrieved 28 October 2022.

Failure of New York to elect electors[change | change source]

Control of the New York State Legislature (government) was divided after the creation of the Constitution, and lawmakers couldn't reach an agreement to appoint (elect) electors for the presidential contest. Federalists, backed by the great landed families and the city commercial interests, were the largest faction in the Senate, the smaller of the two groups. Roughly a quarter of the state's free white male population was allowed to vote, but in the House of Representatives, with its larger membership and voting power, Anti-federalists representing the middling interests held the majority. The fight to ratify the United States Constitution was still fresh in the memories of the lawmakers, and the Anti-Federalists were not happy as they had been forced by events to accept the constitution without changes. Bills to control the selection of electors were brought up in each house and rejected by the other, leading to a sticky situation. The situation continued on January 7, 1789, the last day for electors to be chosen by the states, causing New York to fail to appoint their eight electors.[17][18]

Electoral college selection[change | change source]

The Constitution, in Article II, Section 1, said that the state governments should decide how their Electors were chosen. Governments chose different methods:[19]

Template:Start electoral college selection Template:Electoral college selection row Template:Electoral college selection row Template:Electoral college selection row Template:Electoral college selection row Template:Electoral college selection row Template:Electoral college selection row Template:End electoral college selection

(a) New York's legislature did not choose electors on time.

(b) One electoral district failed to choose an elector.

Related pages[change | change source]

- 1788–89 United States House of Representatives elections

- 1788–89 United States Senate elections

- History of the United States (1789–1849)

Notes[change | change source]

- ↑ New York recognized the Constitution but its state government didn't appoint voters on time, while North Carolina and Rhode Island didn't yet follow the Constitution. Vermont was its own government at the time.

References[change | change source]

- ↑ "National General Election VEP Turnout Rates, 1789-Present". United States Election Project. CQ Press.

- ↑ See "Alternative methods for choosing electors" under Electoral College.

- ↑ Meacham 2012.

- ↑ "Accepting the Presidency". George Washington's Mount Vernon. Retrieved 2023-02-18.

- ↑ "A Saturday Session in the First Congress | US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives". history.house.gov. Retrieved 2023-02-18.

- ↑ Chernow, 272–273.

- ↑ "VP George Clinton". www.senate.gov. Retrieved 2016-04-15.

- ↑ Dubin, Michael J. (2002). United States Presidential Elections, 1788-1860: The Official Results by County and State. Jefferson: McFarland & Company. pp. 1–3. ISBN 9780786410170.

- ↑ Johnson, Charles J. "Edward Telfair". New Georgia Encyclopedia. Retrieved November 24, 2022.

- ↑ "A New Nation Votes".

- ↑ "A New Nation Votes". elections.lib.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2020-12-31.

- ↑ "A New Nation Votes". elections.lib.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2020-12-31.

- ↑ "A New Nation Votes". elections.lib.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2020-12-31.

- ↑ "A New Nation Votes". elections.lib.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2020-12-31.

- ↑ "A New Nation Votes". elections.lib.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2020-12-31.

- ↑ "A New Nation Votes". elections.lib.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2020-12-31.

- ↑ Merrill Jensen, Gordon DenBoer (1976). The Documentary History of the First Federal Elections, 1788-1790. University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 196–197.

- ↑ Ratcliffe, Donald (2013). "The Right to Vote and the Rise of Democracy, 1787-1828". Journal of the Early Republic. 33 (2): 225–229. doi:10.1353/jer.2013.0033. S2CID 145135025.

- ↑ "The Electoral Count for the Presidential Election of 1789". The Papers of George Washington. Archived from the original on September 14, 2013. Retrieved May 4, 2005.

Bibliography[change | change source]

- Bowling, Kenneth R., and Donald R. Kennon. "A New Matrix for National Politics." Inventing Congress: Origins and Establishment of the First Federal Congress. Athens, O.: United States Capitol Historical Society by Ohio U, 1999. 110–37. Print.

- Chernow, Ron (2004). "Alexander Hamilton". London, UK: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-1101200858.

- Collier, Christopher. "Voting and American Democracy." The American People as Christian White Men of Property:Suffrage and Elections in Colonial and Early National America. N.p.: U of Connecticut, n.d, 1999.

- DenBoer, Gordon, ed. (1990). The Documentary History of the First Federal Elections, 1788–1790. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-06690-1.

- Dinkin, Robert J. Voting in Revolutionary America: A Study of Elections in the Original Thirteen States, 1776–1789. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1982.

- Ellis, Richard J. (1999). Founding the American Presidency. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8476-9499-0.

- McCullough, David (1990). John Adams. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4165-7588-7.

- Meacham, Jon (2012). Thomas Jefferson: The Art of Power. Random House. ISBN 978-1-4000-6766-4.

- Novotny, Patrick. The Parties in American Politics, 1789–2016.

- Paullin, Charles O. "The First Elections Under The Constitution." The Iowa Journal of History and Politics 2 (1904): 3-33. Web. February 20, 2017.

- Shade, William G., and Ballard C. Campbell. "The Election of 1788-89." American Presidential Campaigns and Elections. Ed. Craig R. Coenen. Vol. 1. Armonk, NY: Sharpe Reference, 2003. 65–77. Print.

Other websites[change | change source]

- Presidential Election of 1789: A Resource Guide from the Library of Congress

- A New Nation Votes: American Election Returns, 1787–1825

- "A Historical Analysis of the Electoral College". The Green Papers. Retrieved February 17, 2005.

- Election of 1789 in Counting the Votes Archived May 25, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

Template:George Washington Template:John Adams Template:USPresidentialElections Template:1788 United States elections Template:State results of the 1788–89 U.S. presidential election