George Washington

The English used in this article or section may not be easy for everybody to understand. (February 2024) |

The Father of His Country George Washington The US President | |

|---|---|

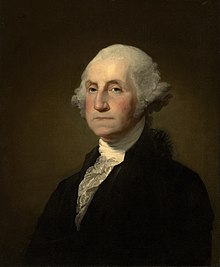

Portrait by Gilbert Stuart, 1796 | |

| 1st President of the United States | |

| In office April 30, 1789[a] – March 4, 1797 | |

| Vice President | John Adams |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | John Adams |

| 7th Senior Officer of the United States Army | |

| In office July 13, 1798 – December 14, 1799 | |

| President | John Adams |

| Preceded by | James Wilkinson |

| Succeeded by | Alexander Hamilton |

| Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army | |

| In office June 14, 1775 – December 23, 1783 | |

| Appointed by | Continental Congress |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Henry Knox as Senior Officer |

| Delegate to the Continental Congress from Virginia | |

| In office May 10, 1775 – June 15, 1775 | |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Jefferson |

| Constituency | Second Continental Congress |

| In office September 5, 1774 – October 26, 1774 | |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished |

| Constituency | First Continental Congress |

| Member of the Virginia House of Burgesses | |

| In office May 18, 1761 – May 6, 1776 | |

| Preceded by | Unknown |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished |

| Constituency | Fairfax County |

| In office July 24, 1758 – May 18, 1761 | |

| Preceded by | Thomas Swearingen |

| Succeeded by | George Mercer |

| Constituency | Frederick County |

| Personal details | |

| Born | February 22, 1732 Popes Creek, Colony of Virginia, British America |

| Died | December 14, 1799 (aged 67) Mount Vernon, Virginia, U.S. |

| Political party | Independent |

| Spouse(s) | Martha Washington/Martha Dandridge (m. 1759) |

| Children | John (adopted) Patsy (adopted) |

| Parents | Augustine Washington Mary Ball Washington |

| Residence | Mount Vernon |

| Awards | Congressional Gold Medal Thanks of Congress[2] |

| Religion | Anglican Church |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1752–58 (Colonial forces) 1775–83 (Continental Army) 1798–99 (U.S. Army) |

| Rank | Colonel (Colonial forces) General and Commander-in-Chief (Continental Army) |

| Commands | Virginia Regiment Continental Army United States Army |

| Battles/wars | French and Indian War |

George Washington (February 22, 1732–December 14, 1799) was the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Before he became president, he was the commander in chief of the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War and one of the Founding Fathers of the United States.

Early life[change | change source]

George Washington was born on February 22, 1732, at his family’s plantation on Pope’s Creek in Westmoreland County, in the British colony of Virginia, to Augustine Washington (1694–1743) and his second wife, Mary Ball Washington (1708–89). George, the eldest of Augustine and Mary Washington’s six children, spent much of his childhood at Ferry Farm, a plantation near Fredericksburg, Virginia. As a teenager, Washington, who had shown an aptitude for mathematics, became a successful surveyor. His surveying expeditions into the Virginia wilderness earned him enough money to begin acquiring land of his own. In 1751, Washington made his only trip outside of America, when he traveled to Barbados with his older half-brother Lawrence Washington (1718–52), who was suffering from tuberculosis and hoped the warm climate would help him recuperate. Shortly after their arrival, George contracted smallpox. He survived, although the illness left him with permanent facial scars. In 1752, Lawrence, who had been educated in England and served as Washington’s mentor, died.

Before the Revolutionary War[change | change source]

In December 1752, Washington, who had no previous military experience, was made commander of the Virginia militia. He failed, and many of his men were killed. The fight opened the French and Indian War, bringing Britain into the Seven Years' War. In 1758, he was elected to the Virginia legislature.

Personal life[change | change source]

In January 1759, he married Martha Dandridge Custis (Martha Washington) (1731–1802), a wealthy widow with two children.

The Revolution[change | change source]

Washington proved to be a better general than a military strategist. His strength lay not in his genius on the battlefield but in his ability to keep the struggling colonial army together. His troops were poorly trained and lacked food, ammunition, and other supplies (soldiers sometimes even went without shoes in the winter). However, Washington was able to give them direction and motivation. His leadership during the winter of 1777–1778 at Valley Forge was a testament to his power to inspire his men to keep going.

By the late 1760s, Washington had experienced firsthand the effects of rising taxes imposed on American colonists by the British and came to believe that it was in the best interests of the colonists to declare independence from England.

Washington was a delegate to the First Continental Congress, which was created by the Thirteen Colonies to respond to various laws passed by the British government. The Second Continental Congress chose him to be the commanding general of the Continental Army. Washington led the army from 1775 until the end of the war in 1783. After losing the big Battle of Long Island, and being chased across New Jersey, Washington led his troops back across the Delaware River on Christmas Day, 1776, in a surprise attack on Hessian mercenaries at the small Battle of Princeton and Trenton, New Jersey. The British had more troops and supplies than Washington; however, Washington kept his troops together and won these small battles.

Overall, Washington did not win many battles, but he never let the British destroy his army. With the help of the French army and navy, Washington made a British army surrender at Yorktown, Virginia, in 1781, as the final major battle of the Revolutionary War. The war officially ended with the Treaty of Paris in 1783.

After the war[change | change source]

When the war ended, Washington was considered a national hero. He was offered a government position that would have been considered a dictatorship over the colonies, but in a surprising move, Washington refused, left the army, and returned to Mount Vernon. He wanted the colonies to have a strong government but did not wish to head that government, nor did he want the colonies to be run by a tyrant.

Washington was one of the men who said the country needed a new constitution. The Constitutional Convention met in 1787, with Washington presiding. The delegates wrote the Constitution of the United States, and all the states ratified it and joined the new government.

Presidency[change | change source]

| Styles of George Washington | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reference style | His Excellency |

| Spoken style | Your Excellency |

| Alternative style | Mr President |

On January 7, 1789, Washington was elected president without any competition, making him the first President of the United States. John Adams (1735–1826), who received the second-largest number of votes, became the nation’s first vice president. The 57-year-old Washington was inaugurated on April 30, 1789, in New York City. Because Washington, D.C., America’s future capital city, wasn’t yet built, he lived in New York and Philadelphia. While Washington did not belong to any political party, he agreed with certain Federalist Party policies, such as that the country should have a standing army and a national bank. While in office, he signed a bill establishing a future, permanent U.S. capital along the Potomac River—the city was later named Washington, D.C., in his honor. He was re-elected to a second term. After his second term, Washington decided not to run for re-election, despite his popularity remaining high. His decision, to stop at 2 terms, set a precedent that every president followed until Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1940.

In Washington's farewell address in 1796, he warned the country not to divide into political parties and not to get involved in wars outside of the United States. Washington's non-intervention foreign policy was supported by most Americans for over one hundred years. His advice to avoid political parties was completely ignored, as parties were already active.

Retirement[change | change source]

Washington went back home to Mount Vernon, Virginia, after his second term ended in 1797.

Death[change | change source]

In December 1799, Washington caught a cold after inspecting his properties in the rain.[3] The cold developed into a throat infection called epiglottitis and Washington died on the night of December 14, 1799, at the age of 67. He was entombed at Mount Vernon, which in 1960 was designated a national historic landmark. Some think that the main cause of his death was bloodletting.[3] This treatment was common at the time. For centuries, It was believed that the best way to extend a person's life or heal them was to "balance the humors"[3]

Wealth[change | change source]

From his marriage, George Washington owned a large amount of farm land, where he grew tobacco, wheat, and vegetables. Washington also owned more than 100 slaves, who were freed upon his death. He did not have much money in cash and had to borrow money while he was president. At his death, Washington's estate was worth over $500,000.[4]

False teeth[change | change source]

It is a common misconception that George Washington had wooden teeth, as false teeth.[5] He did, however, try many different ways to replace his teeth, including having teeth carved from elk's teeth or ivory.[6][7] Ivory and bone both have hairline fractures in them, which normally cannot be seen. These fractures started to darken because Washington drank wine. The darkened, thin fractures in the bone made the lines look like the grain in a piece of wood.[8] George Washington's teeth started falling out when he was about 22 years old, and he had only one tooth left by the time he became president.[6][7] It was difficult for him to talk or to eat. At one time, he had false teeth with a special hole so the one tooth he still had could poke through.[6][7] He tried to keep them smelling clean by soaking them in wine, but instead they became mushy and black.[6][7] In 1796, a dentist had to pull out George Washington's last tooth, and he kept his tooth in a gold locket attached to his watch chain.[6] When the time came for the president to have his portrait painted, cotton was pushed under his lips to make him look as if he had teeth.[6][7] The cotton made his mouth puff out, as is seen on the picture on the US $1 bill.[7]

Notes[change | change source]

References[change | change source]

- ↑ Ferling 2009, p. 274; Taylor 2016, pp. 395, 494.

- ↑ Randall 1997, p. 303.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 "Dec. 14, 1799: The excruciating final hours of President George Washington". PBS NewsHour. 2014-12-14. Retrieved 2023-10-04.

- ↑ Richard Shenkman; Kurt Reiger (1980). One Night Stands with American History. New York: Morrow. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-688-03573-0.

- ↑ Associated Press. "George Washington's false teeth are not wooden." January 27, 2005. Retrieved from http://www.nbcnews.com/id/6875436/#.USNzu1ptUow Archived 2013-02-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 Felton, Bruce. One of a Kind. New York: William Morrow and Co., 1992

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 Gray, Ralph, ed. Small Inventions That Make a Big Difference. Washington, D.C.: The National Geographic Society, 1984

- ↑ "Drilling Holes in George Washington's Wooden Teeth Myth". 5 November 2014. Archived from the original on 2015-03-18. Retrieved 2015-03-09.

Sources[change | change source]

- Nettleton, Pamela Hill (2004). George Washington: Farmer, Soldier, President. Capstone. ISBN 978-1-4048-0184-4.

- Santrey, Laurence (January 1, 2002). George Washington: Young Leader (Easy Biographies). Troll Communications Llc. ISBN 978-0816774340.

- Usel, T. M. (1996). George Washington: A Photo-Illustrated Biography. Bridgestone Books. ISBN 978-1-56065-340-0.

- Polack, Peter (2018). Guerrilla Warfare: Kings of Revolution. Casemate Short History. ISBN 978-1-61200-675-8.

- Randall, Willard Sterne (1997). George Washington: A Life. Henry Holt & Co. ISBN 978-0805027792.

- Ferling, John E. (2009). The Ascent of George Washington: The Hidden Political Genius of an American Icon. Bloomsbury Press. ISBN 978-1608191826.

- Taylor, Alan (2016). American Revolutions: A Continental History, 1750–1804. W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0393354768.

- Washington's White House biography Archived 2007-10-11 at the Wayback Machine

- Presidents of the United States

- 1732 births

- 1799 deaths

- American esotericists

- American generals

- American revolutionaries

- Businesspeople from Virginia

- Chancellors of the College of William & Mary

- Episcopalians

- Founding Fathers of the United States

- Freemasons

- George Washington

- Military people from Virginia

- Politicians from Virginia

- 18th-century American politicians

- Independent politicians in the United States

- Infectious disease deaths in Virginia

- Libertarians

- Nationalists