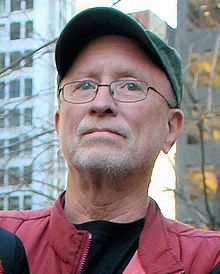

Bill Ayers

Bill Ayers | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | William Charles Ayers December 26, 1944 Glen Ellyn, Illinois, U.S. |

| Education | University of Michigan (BA) Bank Street College of Education (MEd) Columbia University (MEd, EdD) |

| Known for | Founder of the Weather Underground Urban educational reform |

| Spouse | Bernardine Dohrn |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Education |

| Institutions | University of Illinois at Chicago |

William Charles "Bill" Ayers (born December 26, 1944)[1] is an American elementary education theorist. He is a former head of the Weather Underground. Ayers is known for speaking out against the Vietnam War in the 1960s. He is also known for his current work in trying to help make learning and teaching better. In 1969, Ayers started the Weather Underground. The Weather Underground is a group that call themselves a "communist revolutionary group".[2] They carried out bombings against public buildings during the 1960s and 1970s. This was because the United States was being a part of the Vietnam War. Ayers is a professor in the College of Education at the University of Illinois at Chicago. He has the titles of Distinguished Professor of Education and Senior University Scholar. During the 2008 U.S. presidential election, a controversy was brought up over ties between Ayers and then Senator Barack Obama. Ayers is married to Bernadine Dohrn. She was also a member of the Weather Underground.

Early life

[change | change source]Bill Ayers grew up in Glen Ellyn, Illinois. Glen Ellyn is just outside Chicago. He went to public schools there until his second year of high school. After this he started going to Lake Forest Academy. It is a smaller prep school.[3] Ayers received a B.A. from the University of Michigan in American studies in 1968.[3] He is the son of Thomas G. Ayers. His father used to be chairman and CEO of Commonwealth Edison.[4]

In 1965, Ayers was part of a group who were protesting at a restaurant in Ann Arbor, Michigan. The restaurant would not serve African Americans. Ayers' first arrest came when he took part in a sit-in at a local draft board. He sat in jail for ten days. Shortly after his arrest, he landed his first teaching job at the Children's Community School. This small preschool was run from a local church basement.[5] The preschool was part of a larger movement across the United States called the "free school movement". Schools that were part of this movement had no grades or report cards. Instead, they tried to work on getting students to cooperate with each other and work together instead of competing. The teachers allowed the students to call them by their first names. After teaching for only a few months, at the age of 21, Ayers became the head of the school. There he also met Diana Oughton, who would be his girlfriend until her death in an explosion in 1970.[3]

Beginnings with the Weathermen

[change | change source]Ayers became part of the New Left and the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) in the early 1960s.[6] In 1968 and 1969, Ayers became well known as a head of the SDS. He was head of a smaller SDS group called the "Jesse James Gang". Ayers made important changes to Weatherman beliefs about being militant (ready to fight for the cause).[7] The group that Ayers headed in Detroit, Michigan became one of the first groups that would turn into the Weathermen. Before the June 1969 SDS convention, Ayers became an important head of the group. This came about due to a split in the group.[7]

In June 1969, the Weathermen took over the SDS at its convention. Ayers was made Education Secretary.[7] Later in 1969, Ayers helped to place a bomb at a statue that was made to honor policemen that were killed.[8] The bomb blast broke almost 100 windows and blew parts of the statue onto a nearby street.[9] (The statue was rebuilt and unveiled on May 4, 1970, and blown up again by other Weathermen on October 6, 1970.[9][10] While they were putting it back together, the city put a 24-hour guard around it to stop another attack. In January 1972, it was moved to Chicago Police headquarters.[11] Ayers was also part of the Days of Rage riot that took place in Chicago in 1969. He was also a part of the "War Council" meeting that happened in Flint, Michigan. Two big decisions came from the "War Council". The first was to start a violent, armed resistance (using bombs, and robberies) against the government. The second was to start underground (secret) groups in important cities around the country.[12] An FBI informant named Larry Grathwohl, who pretended to be a Weatherman in 1969, said that "Ayers, along with Bernardine Dohrn, probably had the most authority within the Weatherman".[13]

Years underground

[change | change source]In 1970, Weatherman members Ted Gold, Terry Robbins, and Diana Oughton were killed when a bomb they were building blew up. This was called the Greenwich Village town house explosion. Ayers and several other Weathermen were able to avoid being caught following this explosion. Ayers was not facing charges at this time, but the federal government later brought charges against him.[3] Ayers was part of the bombings of New York City Police Department headquarters in 1970, the United States Capitol building in 1971, and the Pentagon in 1972. Ayers wrote, in 2001, that:

Although the bomb that rocked the Pentagon was itsy-bitsy - weighing close to two pounds - it caused 'tens of thousands of dollars' of damage. The operation cost under $500, and no one was killed or even hurt.[14]

Some new reports have said that Ayers, Dohrn, or the Weatherman took part in the 1970 San Francisco Police Department bombing. However, neither Ayers, nor anyone else has ever been charged with this crime.[15]

In 1973, it was discovered that the FBI were focusing on the Weatherman as well as the New Left. This was part of several secret, and sometimes illegal FBI projects called COINTEL.[16] Because the FBI agents had broken the law, the government asked that all weapons and bomb charges be dropped against the Weather Underground. This included charges against Ayers.[17]

However, there were still state charges against Dohrn. Dohrn did not want to turn herself in to the police. "He was sweet and patient, as he always is, to let me come to my senses on my own", she later said of Ayers.[3] She finally turned herself in, in 1980. She was fined $1,500 and given three years probation.[18]

In 1973 Ayers helped write the book Prairie Fire[19] with others who were part of the Weather Underground. They dedicated the book to almost 200 people, including Harriet Tubman, John Brown, 'All Who Continue to Fight', 'All Political Prisoners in the U.S.', and Sirhan Sirhan, who was convicted of killing Robert F. Kennedy.[20][21]

Looking back on the underground period

[change | change source]Fugitive Days: A Memoir

[change | change source]In 2001, Ayers wrote Fugitive Days: A Memoir. He said Fugitive Days tried to answer the questions of Kathy Boudin's son and his statement that Diana Oughton died trying to stop the Greenwich Village bomb makers.[22] Some have questioned the truth, accuracy, and tone of the book. Brent Staples wrote for The New York Times Book Review that "Ayers reminds us often that he can't tell everything without endangering people involved in the story.[23] Historian Jesse Lemisch (who was also a member of the SDS) said that Ayers' memories were wrong.[24] Ayers, in the beginning of his book, says that it was written as his personal memories and was not a research project.[25]

Statements made in 2001

[change | change source]Chicago Magazine said that "just before the September 11 attacks", Richard Elrond, who was hurt in the "Days of Rage", was given an apology from Ayers and Dohrn. "[T]hey were remorseful," Elrod says. "They said, 'We're sorry that things turned out this way.'"[26] Ayers gave a lot of interviews before his book was published. In these interviews he defended his history of radical words and actions. Some of the articles were written before the September 11 attacks and appeared right after. Many comments were made by the media comparing the statements that Ayers was making about his past just as a terrorist incident shocked the public.

A lot of the controversy about Ayers in the years since 2000 comes from an interview that he gave to The New York Times.[27] The reporter quoted him as saying "I don't regret setting bombs" and "I feel we didn't do enough". When asked if he would "do it all again," he said "I don't want to discount the possibility."[25] Ayers questioned the interviewer's way of describing him in a "Letter to the Editor" on September 15 2001. In his letter, Ayers wrote: "This is not a question of being misunderstood or 'taken out of context', but of deliberate distortion."[28] In the following years, Ayers has said that what he meant by saying that he had "no regrets" and "we didn't do enough" he was talking about their efforts to stop the US from fighting in the Vietnam War. He said these efforts were ". . . inadequate [as] the war dragged on for a decade."[29] Ayers has repeatedly said that the two statements did not mean that he wished they had set more bombs.[29][30]

Views since 2001

[change | change source]Ayers was asked in a 2004 interview, "How do you feel about what you did? Would you do it again under similar circumstances?" He said:[31] "I've thought about this a lot. Being almost 60, it's impossible to not have lots and lots of regrets about lots and lots of things, but the question of did we do something that was horrendous, awful? ... I don't think so. I think what we did was to respond to a situation that was unconscionable." On September 9, 2008, journalist Jake Tapper talked about the comic strip in Ayers' blog, where he explained the soundbite: "The one thing I don't regret is opposing the war in Vietnam with every ounce of my being.... When I say, 'We didn't do enough,' a lot of people rush to think, 'That must mean, "We didn't bomb enough shit."' But that's not the point at all. It's not a tactical statement, it's an obvious political and ethical statement. In this context, 'we' means 'everyone.'"[32][33]

In 2008, Ayers said this about his actions:

The Weather Underground crossed lines of legality, of propriety and perhaps even of common sense. Our effectiveness can be — and still is being — debated.[34]

He also again defended his actions against charges of terrorism:

The Weather Underground went on to take responsibility for placing several small bombs in empty offices.... We did carry out symbolic acts of extreme vandalism directed at monuments to war and racism, and the attacks on property, never on people, were meant to respect human life and convey outrage and determination to end the Vietnam war.[34]

Political views

[change | change source]In an interview that Ayers gave in 1995, he said of his political beliefs in the 1960s and 1970s: "I am a radical, Leftist, small 'c' communist ... [Laughs] Maybe I'm the last communist who is willing to admit it. [Laughs] We have always been small 'c' communists in the sense that we were never in the Communist party and never Stalinists. The ethics of communism still appeal to me. I don't like Lenin as much as the early Marx. I also like Henry David Thoreau, Mother Jones and Jane Addams [...]"[35] In 1970 Ayers was called "a national leader"[36] of the Weatherman organization and "one of the chief theoreticians of the Weathermen" by The New York Times.[37]

The Weatherman started off as part of the Revolutionary Youth Movement (RYM) within the SDS. They split from the RYM's Maoists saying they had no time to build another party. They also said that war against the United States government and capitalism should begin right away. Their founding paper called for the creation of a "white fighting force" to fight with the "Black Liberation Movement" and other "anti-colonial' movements.[38] to achieve "the destruction of US imperialism and the achievement of a classless world: world communism."[39] In June 1974, the Underground released their 151-page work called "Prairie Fire". "Prairie Fire" said that: "We are a guerrilla organization [...] We are communist women and men underground in the United States [...]"[40] The Weatherman's leaders, including Ayers, wanted radical changes to sexual relations and used the slogan "Smash Monogamy".[41][42]

Claims by Grathwohl

[change | change source]Larry Grathwohl, who was an FBI agent who joined the Underground, said that Ayers wanted to overthrow the United States government. In an interview that he gave in January 2009, Grathwohl said that:

"The thing the most bone chilling thing Bill Ayers said to me was that after the revolution succeeded and the government was overthrown, they believed they would have to eliminate 25 million Americans who would not conform to the new order."[43]

Ayers replied:

"Never said it. Never thought it. And again, Larry Grathwohl, I don't know him today, but certainly the FBI was an organization built on lies."[43]

In an interview with ABC7 reporter Alan Wang, Ayers said that "Now that's being blown into dishonest narratives about hurting people, killing people, planning to kill people. That's just not true. We destroyed government property," said Ayers. However, when asked if he ever made bombs, Ayers replied: "I'm just not going to talk about it."[43]

Relationship with President Obama

[change | change source]During the 2008 U.S. presidential election, a controversy started about Ayers' contact with then-Senator Barack Obama. This had been well known in Chicago for years.[44] After being raised by the British press[44][45][46] The ties between Ayers and Obama was written about by blogs and newspapers in the United States. The issue was also talked about in a debate by moderator George Stephanopoulos. It later became an issue for John McCain's campaign. "The New York Times", CNN, and several other news groups said that Obama does not have a close friendship with Ayers.[47][48][49] After the election, Ayers said he did not have any close ties with Obama and condemned the Republicans for using "guilt by association" tactics.[34] In a new afterword to his book, he added a note saying that he knew the Obamas "as neighbors and family friends."[50] But in an interview with Good Morning America, Ayers said the afterword was "describing there how the blogosphere characterized the relationship."[51]

Academic career

[change | change source]Ayers teaches at the University of Illinois at Chicago. He mainly focuses on social justice, fixing education in urban areas, children who are in trouble with the law and related issues.[52]

He began working as a teacher at the Children's Community School (CCS). CCS was started by a group of students and based on the Summerhill way of teaching. After he left the underground, he earned an Masters in Education (M.Ed.) from Bank Street College in Early Childhood Education (1983)), an M.Ed. from Teachers College, Columbia University in Early Childhood Education (1987) and an Ed.D. from Teachers College, Columbia University in Curriculum and Instruction (1987).

He has edited and written many books and articles. They usually have to deal with education. He has also been on many panels and symposia.

Personal life

[change | change source]Ayers is married to Bernardine Dohrn. Dohrn was also part of the Weather Underground. They have two adult children and they share custody of Chesa Boudin. Boudin is the son of two former Underground members who were put in jail. Chesa Boudin went on to win a Rhodes Scholarship.[53] Ayers and Dohrn live in the Hyde Park neighborhood of Chicago.[54]

In 1997 Chicago awarded him its Citizen of the Year award for his work on the Chicago Annenberg Challenge project.[55]

References

[change | change source]- ↑ "Weatherman Underground" (PDF). FBI. 20 August 1976. Retrieved 2008-10-18.

- ↑ The Weathermen's founding manifesto, signed by Ayers and ten others, says, "The most important task for us toward making the revolution, and the work our collectives should engage in, is the creation of a mass revolutionary movement...akin to the Red Guard in China, based on the full participation and involvement of masses of people...with a full willingness to participate in the violent and illegal struggle. Ayers, Bill (1969). You Don't Need a Weatherman to Know Which Way the Wind Blows. Mark Rudd, Bernardine Dohrn, Jeff Jones, Terry Robbinson, Gerry Long, Steve Tappis et al. Weatherman. p. 28. Retrieved 2009-11-19.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Terry, Don (Chicago Tribune staff reporter), "The calm after the storm", Chicago Tribune Magazine, p 10, September 16, 2001, June 8, 2008

- ↑ Jackson, Cheryl V. (June 12, 2007). "Former ComEd CEO; Businessman also fought for equality". Chicago Sun-Times. p. 49. Retrieved 2008-10-09.

- ↑ Before "going underground" he published an account of this experience, Education: An American Problem.

- ↑ Fugitive Days: A Memoir

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Barber, David, "Fugitive Days; A Memoir - Book Review", Journal of Social History, Winter 2002, retrieved June 10, 2008

- ↑ Jacobs, Ron, The way the wind blew: a history of the Weather Underground, London & New York: Verso, 1997. ISBN 1-85984-167-8

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Avrich. The Haymarket Tragedy. p. 431.

- ↑ Adelman. Haymarket Revisited, p. 40.

- ↑ Haymarket Memorial Statue Rededicated at Chicago Police Headquarters Archived 2009-01-20 at the Wayback Machine Chicago Police Department, June 1, 2007

- ↑ Good, "Brian Flanagan Speaks," Next Left Notes, 2005.

- ↑ Grathwohl, Larry, and Frank, Reagan, Bringing Down America: An FBI Informant in with the Weathermen, Arlington House, 1977, page 110

- ↑ Bill Ayers, Fugitive Days, pg. 261

- ↑ USA Survival website Archived 2010-06-13 at the Wayback Machine - this is website of a political group opposed to Ayers, they have various pages devoted to the San Francisco bombing

- ↑ "Why Weren't Bill Ayers and Bernadette Dohrn Convicted of Terrorism?". Archived from the original on 2010-12-30. Retrieved 2010-03-12.

- ↑ Jeremy Varon, Bringing The War Home: The Weather Underground, The Red Army Faction And Revolutionary Violence In The Sixties And Seventies, (Berkley: University of California Press, 2004), 297.

- ↑ Susan Chira, At home with: Bernadine Dohrn; Same Passion, New Tactics, The New York Times, November 18, 1993

- ↑ "William Ayers' forgotten communist manifesto: Prairie Fire". Retrieved 2010-03-12.

- ↑ Blogspot.com, Dedication page, Prairie Fire

- ↑ Harvey E. Klehr (1991) Far Left of Center: The American Radical Left Today, Transaction Publishers, p 108 ISBN 0-88738-875-2

- ↑ Marcia Froelke Coburn, No Regrets, Chicago Magazine, August 2001

- ↑ Staples, Brent, "The Oldest Rad", book review of Fugitive Days by Bill Ayers in New York Times Book Review, September 30, 2001, accessed June 5, 2008

- ↑ Jesse Lemisch, Weather Underground Rises from the Ashes: They're Baack! Archived 2008-12-01 at the Wayback Machine, New Politics, Summer 2006

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Dinitia Smith, No Regrets for a Love Of Explosives; In a Memoir of Sorts, a War Protester Talks of Life With the Weathermen, The New York Times, September 11, 2001

- ↑ Bryan Smith (December 2006). "Sudden Impact". Chicago Magazine. Retrieved 2008-10-18.

- ↑ NB that although the interview was published on 9/11, it was completed before that and cannot be properly regarded as a reaction to the events of that day.

- ↑ Bill Ayers, Clarifying the Facts— a letter to the New York Times, 9-15-2001, Bill Ayers (blog), April 21, 2008

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Bill Ayers, Episodic Notoriety–Fact and Fantasy, Bill Ayers (blog), April 6, 2008

- ↑ Bill Ayers, WordPress.com, I'm Sorry!!!!... I think, Bill Ayers (blog)

- ↑ Web page titled "Weather Underground/ Exclusive interview: Bernardine Dohrn and Bill Ayers" Archived 2017-08-31 at the Wayback Machine, Independent Lens website, accessed June 5, 2008

- ↑ Bill Ayers: Violent Resistance Not Necessarily the Answer Blog post in Little Green Footballs with a copy of the cartoon including the word "shit"

- ↑ Tapper, Jake In a Not-Remotely-Comic Strip, Bill Ayers Weighs In on What He Meant By 'We Didn't Do Enough' to End Vietnam War ABC News, Political Punch, September 9, 2008

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 Ayers, William (December 6, 2008), "The Real Bill Ayers", The New York Times, pp. A21

- ↑ Chepesiuk, Ron, "Sixties Radicals, Then and Now: Candid Conversations With Those Who Shaped the Era", McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers: Jefferson, North Carolina, 1995, "Chapter 5: Bill Ayers: Radical Educator", p. 102

- ↑ Flint, Jerry, M., "2d Blast Victim's Life Is Traced: Miss Oughton Joined a Radical Faction After College", news article, The New York Times, March 19, 1970

- ↑ Kifner, John, "That's what the Weathermen are supposed to be ... 'Vandals in the Mother Country'", article, The New York Times magazine, January 4, 1970, page 15

- ↑ Berger, Dan (2006). Outlaws of America: The Weather Underground and the Politics of Solidarity. AK Press. p. 95. ISBN 9781904859413.

- ↑ See document 5, Revolutionary Youth Movement (1969). "You Don't Need a Weatherman to Know Which Way the Wind Blows". Archived from the original on 2006-03-28. Retrieved 2008-04-11.

- ↑ Franks, Lucinda, "U.S. Inquiry Finds 37 In Weather Underground", news article, The New York Times, March 3, 1975

- ↑ Ron Jacobs, The Way the Wind Blew, p. 46.

- ↑ No Regrets for a Love Of Explosives; In a Memoir of Sorts, a War Protester Talks of Life With the Weathermen NY Times, Sep 11, 2001

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 Ayers' speech interrupted by protesters Archived 2009-02-01 at the Wayback Machine by Alan Wang, ABC7 News, KGO-TV San Francisco, January 28, 2009.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Weiss, Joanna (2008-04-18). "How Obama and the radical became news". The Boston Globe.

- ↑ Hitchens, Peter (2008-02-02). "The Black Kennedy: But does anyone know the real Barack Obama?". Daily Mail.

- ↑ Dobbs, Michael (2008-02-19). "Obama's 'Weatherman' Connection". The Fact Checker. The Washington Post.

- ↑ Shane, Scott (3 October 2008). "Obama and '60s Bomber: A Look Into Crossed Paths". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-10-12.

- ↑ "Fact Check: Is Obama 'palling around with terrorists'?". CNN. 5 October 2008. Archived from the original on 2008-10-13. Retrieved 2008-10-12.

- ↑ "Palin hits Obama for 'terrorist' connection". CNN. 2008-10-05. Archived from the original on 2015-06-22. Retrieved 2010-03-12.

- ↑ "Bill Ayers Says Obama Was 'Family Friend'". CNS. 2008-11-14.[permanent dead link]

- ↑ "Former Radical: Obama not a Close Friend". AP. Retrieved 2010-03-24.

- ↑ "University of Illinois at Chicago, College of Education". Archived from the original on 2008-09-30. Retrieved 2010-03-12.

- ↑ Jodi Wilgoren (December 9, 2002). "From a Radical Background, A Rhodes Scholar Emerges". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-10-18.

- ↑ Fusco, Chris; Pallasch, Abdon M. (April 18, 2008). "Who is Bill Ayers?". Chicago Sun-Times. p. 8. Archived from the original on 2008-10-08. Retrieved 2008-10-05.

- ↑ Drew Griffin; Kathleen Johnston (October 7, 2008). "Ayers and Obama crossed paths on boards, records show". CNN. Retrieved 2008-10-08.

Other websites

[change | change source]- Official website

- Ayers' Blog

- Which Way The Wind Blows: Bill Ayers On Obama Post-election interview with Bill Ayers by Terry Gross of NPR's Fresh Air, November 18, 2008.

- November 2008, radio interview on Democracy Now! part one part two

- Transcript of interview in 1996 with Bernardine Dohrn and Bill Ayers Archived 2014-01-01 at the Wayback Machine, PBS