User talk:Doc James/Urinary tract infection

| Urinary tract infection | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

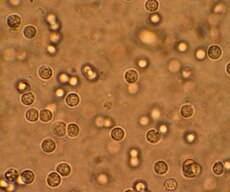

Multiple white cells seen in the urine of a person with a urinary tract infection using a microscope | |

| ICD-10 | N39.0 |

| ICD-9 | 599.0 |

| DiseasesDB | 13657 |

| MedlinePlus | 000521 |

| eMedicine | emerg/625 emerg/626 |

| MeSH | D014552 |

A urinary tract infection (UTI) is a bacterial infection in part of the urinary tract. When it affects the lower urinary tract, it is known as a simple cystitis (a bladder infection). When it affects the upper urinary tract, it is known as pyelonephritis (a kidney infection). Symptoms from a lower urinary tract include painful peeing and either frequent peeing or urge to pee (or both). Symptoms of a kidney infection also include a high body temperature and side and back pain. In old people and young children, the symptoms are not always as clear. The main cause for both types is the bacteria Escherichia coli. In rare cases, however, other bacteria, viruses, or fungus may be the cause.

Urinary tract infections are more common in women than men. Half of women have an infection at some point in their lives. It is common to have repeated infections. Risk factors include sexual intercourse as well as family history. Kidney infection can follow a bladder infection. Kidney infection also can be caused by a blood borne infection. Diagnosis in young healthy women can be based on symptoms alone. Diagnosis can be difficult in people whose symptoms are not clear because bacteria can be present even though the person does not have an infection. In complicated cases or if treatment does not work, a urine culture is sometimes useful. A person with frequent infections can take low-dose antibiotics to prevent future infections.

Simple cases of urinary tract infections are easily treated with a short course of antibiotics. resistance to many of the antibiotics used to treat this condition, however, is increasing. People who have complicated urinary tract infections sometimes have to take antibiotics for a longer period of time, or might take intravenous antibiotics. If symptoms have not improved in two or three days, a person will need further tests. In women, urinary tract infections are the most common form of bacterial infection. Ten percent of women develop urinary tract infections yearly.

Signs and symptoms

[change source]

Lower urinary tract infection is also known as a bladder infection. The most common symptoms are burning with peeing and having to pee frequently (or an urge to pee) without vaginal discharge or significant pain.[1] These symptoms can vary from mild to severe[2]. In healthy women, the symptoms last an average of six days.[3] Some people will have pain above the pubic bone (lower abdomen) or in the lower back. People who have an upper urinary tract infection, or pyelonephritis (a kidney infection), can have flank pain, fever (a high temperature), or nausea and vomiting. Those symptoms are in addition to the normal symptoms of a lower urinary tract infection.[2] Rarely, the urine appears bloody[4] or contains visible pyuria (pus in the urine).[5]

In children

[change source]In young children, the only symptom of a urinary tract infection (UTI) can be a fever. Many medical associations recommend a urine culture when females under the age of two or uncircumcised males who are younger than a year have a fever. Infants with UTI sometimes eat poorly, vomit, sleep more, or show signs of jaundice ( a yellow coloring of the skin). Older children can have new urinary incontinence (loss of bladder control).[6]

In the elderly

[change source]Urinary tract symptoms are frequently not present in those who are old.[7] Sometimes, the only symptoms are incontinence (loss of bladder control), a change in mental status (ability to think), or felling tiered.[2] The first symptom for some old people is sepsis, an infection of the blood.[4] Diagnosis can be complicated because many old people are incontinent or have dementia (poor thinking abilities).[7]

Cause

[change source]E. coli is the cause of 80–85% of urinary tract infections. Staphylococcus saprophyticus is the cause in 5–10% of cases.[1] Rarely, urinary tract infections are due to viral or fungal infections.[8] Other bacterial causes include:Klebsiella, Proteus, Pseudomonas, and Enterobacter. These bacterial causes are not common and typically are found when there are abnormalities of the urinary system or the person has a urinary catheterization.[4] Urinary tract infections due toStaphylococcus aureus usually follows a blood born infections.[2]

Gender

[change source]Sex is the cause of 75–90% of bladder infections in young, sexually active women. The risk of infection is related to the frequency of sex.[1] With UTIs so frequent when women first get married, the term "honeymoon cystitis" is often used. In post-menopausal women, sexual activity does not affect the risk of developing a UTI. Spermicide use increases the risk of UTIs.[1]

Women get more UTIs than men because women have a urethra that is much shorter and closer to the anus.[9] As a woman's estrogen (a hormone) levels decrease with menopause, the risk of urinary tract infections increases due to the loss of protective vaginal flora (good bacterial that live in the vagina).[9]

Urinary catheters

[change source]A urinary catheter, a tube which is put into the bladder to drain pee, increases the risk for urinary tract infections. The risk of bacteriuria(bacteria in the urine) is 3% - 6% per day the catheter is in. Antibiotics are not effective in preventing these infections.[9] The risk of an associated infection can be decreased by using a catheter only when necessary, making sure everything is sterile when putting the catheter in, and making sure that the catheter drains without anything blocking it. [10][11][12]

Others

[change source]Bladder infections are more common in some families. Other risk factors include diabetes,[1] being circumcised, and having a large prostate (a gland that surrounds the urethra in males).[2] Complicating factors are not completely clear. These factors may include some anatomic problems (relating to physical narrowing), functional, or metabolic problems. A complicated UTI is more difficult to treat and usually requires more aggressive evaluation, treatment, and follow-up.[13] In children, UTIs are associated with vesicoureteral reflux (an abnormal movement of urine from the bladder into ureters or kidneys) and constipation.[6]

Pathogenesis

[change source]The bacteria that cause urinary tract infections typically enter the bladder via the urethra. However, infections can also come through the blood or lymph. It is believed that the bacteria go into the urethra come from the bowel. Females are at greater risk due to their anatomy (due to having a short urethra and their urethra being close to their anus). After entering the bladder, E. Coli are able to attach to the bladder wall and form a biofilm (a coating of microorganisms) that resists the body's immune response.[4]

Prevention

[change source]A number of measures have not been proven to change UTI frequency. These measures include using birth control pills or condoms, urinating immediately after sex, the type of underwear used, personal cleaning methods used after urinating or defecating, or whether a person typically baths or showers.[1] There is also no clear evidence that holding urine, tampon use, and douching can cause UTIs.[9]

People who frequently get urinary tract infections and who use spermicide or a diaphragm as a method of birth control are advised to use alternative methods.[4] Cranberry (juice or capsules) may decrease the incidence in people with frequent infections. Long-term tolerance for the cranberries, however, can be a problem.[14] Gastrointestinal (stomach) upset occurs in more than 30% of people who regularly drink cranberry juice or take capsules.[15] As of 2011, probiotics used intravaginally (in the vagina) require further study to determine if they are helpful.[4]

Medications

[change source]For people with recurrent infections, a long course of daily antibiotics is effective.[1] Medications frequently used include nitrofurantoin and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole. If infections are related to intercourse (sexual relations), some women find it useful to taking antibiotics after intercourse.[4] In post-menopausal women, topical vaginal estrogen (a hormone) has been found to reduce recurrence. Unlike topical creams, the use of vaginal estrogen from pessaries is not as useful as low-dose antibiotics.[16] A number of vaccines are in development as of 2011.[4]

In children

[change source]The evidence that preventative antibiotics decrease urinary tract infections in children is poor.[17] It is rare for people who have no problems with their kidney to develop kidney problems from recurrent UTIs. Frequent urinary tract infections as a child are the cause of less than a third of a percent (0.33%) of chronic kidney disease in adults.[18]

Diagnosis

[change source]

In straightforward cases, laboratory testing is not needed and UTIs can be diagnosed based on symptoms alone. Urinalysis (testing the urine) can be used to confirm the diagnosis in complicated cases, looking for the presence of urinary nitrites, white blood cells (leukocytes), or leukocyte esterase. Another test, urine microscopy, looks for the presence of red blood cells, white blood cells, or bacteria. Urine culture is considered positive if it shows a bacterial colony count of greater than or equal to 103 colony-forming units per mL of a typical bacteria that causes infections of the urinary tract. Cultures can also be used to test which antibiotic will work. However, women with negative cultures can still improve with antibiotic treatment.[1] UTI symptoms in old people can be vague, and diagnosis can be difficult as there is no really reliable test.[7]

Classification

[change source]A urinary tract infection involving only the lower urinary tract is known as a bladder infection. A UTI involving the upper urinary tract is known as pyelonephritis or kidney infection. If the urine contains significant bacteria, but there are no symptoms, the condition is known as asymtomatic bacteriuria.[2] If a urinary tract infection involves the upper tract, the person has diabetes mellitus, is pregnant, is male, or immunocompromised (a weakened immune system due to another illness), the UTI is considered complicated.[4][3] Otherwise if a women is a healthy and before menopause, the infection is considered uncomplicated.[3] When children also have a fever, the urinary tract infection is considered to be a upper urinary tract infection.[6]

In children

[change source]To diagnose a urinary tract infection in children, a positive urinary culture is required. Contamination poses a frequent challenge so a cutoff of 105 CFU/mL is used for a "clean-catch" mid-stream sample, 104 CFU/mL is used for catheter-obtained specimens, and 102 CFU/mL is used for suprapubic aspirations (a sample drawn directly from the bladder through the stomach wall with a needle). The World Health Organization discourages the use of “urine bags” to collect samples due to the high rate of contamination when that urine is cultured. Catheterization is preferred if an individual is unable to use a toilet. Some medical groups, such as the American Academy of Pediatrics, recommend renal ultrasound and voiding cystourethrogram (watching a person's urethra and urinary bladder with real time X-rays while they urinate) in all children who are younger than two years old and have had a urinary tract infection.However, because there is a lack of effective treatment if problems are found, others medical groups such as the National Institute for Clinical Excellence recommend routine imaging only in babies less than six months old or who have unusual findings.[6]

Differential diagnosis

[change source]In women with cervicitis (inflammation of the cervix) or vaginitis (inflammation of the vagina) and in young men with UTI symptoms, a Chlamydia trachomatis or Neisseria gonorrheae infection may be the cause.[19][2] Vaginitis may also be due to a yeast infection.[20] Interstitial cystitis (chronic pain in the bladder) can be the cause for people who experience multiple episodes of UTI symptoms, but whose urine cultures remain negative and do not improved with antibiotics.[21] Prostatitis (inflammation of the prostate) may also be considered in the differential diagnosis.[22]

Treatment

[change source]Phenazopyridine can be used in addition to antibiotics to help ease the burning of a bladder infection.[23] However, phenazopyridine is no longer commonly recommended due to safety concerns, specifically an elevated risk of methemoglobinemia (higher than normal level of methemoglobin in the blood).[24] Acetaminophen can be used for fevers.[25]

Women with recurrent simple UTIs can benefit from self-treatment; medical follow-up will be required only if the initial treatment fails. Health care providers may also prescribe the antibiotics by phone.[1]

Uncomplicated

[change source]Uncomplicated infections can be diagnosed and treated based on symptoms alone.[1] Oral antibiotics such as trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX), cephalosporins, nitrofurantoin, or a fluoroquinolone substantially shorten the time to recovery. All these medications are equally effective.[26] A three-day treatment with trimethoprim, TMP/SMX, or a fluoroquinolone is usually sufficient. Nitrofurantoin requires 5-7 days.[1][27] With treatment, symptoms should improve within 36 hours.[3] About 50% of people will recover without treatment within a few days or weeks.[1] The Infectious Diseases Society of America does not recommend fluoroquinolones as first treatment because of concerns that overuse will lead to resistance to this class of medication, making this medication less effective for more serious infections.[27] Despite this precaution, some resistance has developed to all of these medications related to their widespread use.[1] In some countries, trimethoprim alone is deemed to be equivalent to TMP/SMX.[27] Children with simple UTIs are often helped by a three-day course of antibiotics.[28]

Pyelonephritis

[change source]Pyelonephritis (kidney infection) is treated more aggressively than a simple bladder infection using either a longer course of oral antibiotics or intravenous antibiotics.[29] Seven days of the oral fluoroquinolone ciprofloxacin is typically used in geographic areas where the resistance rate is less than 10%. If the local resistance rates are greater than 10%, a dose of intravenous ceftriaxone often is prescribed. People with more severe symptoms are sometimes admitted a hospital for ongoing antibiotics.[29] If symptoms do not improve following two or three days of treatment, complications such as blockage of the urinary tract from a kidney stone are considered.[29][2]

Epidemiology

[change source]Urinary tract infections are the most frequent bacterial infection in women.[3] They occur most frequently between the ages of 16 and 35 years. Ten percent of women get an infection yearly; 60% have an infection at some point in their lives.[1][4] Recurrences are common, with nearly half of people getting a second infection within a year. Urinary tract infections occur four times more frequently in females than males.[4]Pyelonephritis (a kidney infection) occurs between 20–30 times less frequently than bladder infections.[1] Pyelonephritis is the most common cause of hospital acquired infections, accounting for approximately 40% of hospital-acquired infections.[30] Rates of asymptomatic bacteria in the urine increase with age from 2% to 7% in women of childbearing age to as high as 50% in elderly women in care homes.[9] Rates of aysmtomatic bacteria in the urine among men over 75 are 7-10%.[7]

Urinary tract infections can affect 10% of people during childhood.[4] Urinary tract infections in children are the most common in uncircumcised males younger than three months of age, followed by females younger than one year.[6] Estimates of frequency among children, however, vary widely. In a group of children with a fever, ranging in age between birth and two years, 2- 20% were diagnosed with a UTI.[6]

Society and culture

[change source]In the United States, urinary tract infections account for nearly seven million office visits, a million emergency department visits, and 100,000 hospitalizations every year.[4] The cost of these infections is significant both in terms of lost time at work and costs of medical care. The direct cost of treatment is estimated at 1.6 billion USD yearly in the United States.[30]

History

[change source]Urinary tract infections have been described since ancient times. The first written description, found in the Ebers Papyrus, dates to around the 1550 BC.[31] The Egyptians described a urinary tract infection as "sending forth heat from the bladder."[32] Herbs, bloodletting, and rest were the common treatments until the 1930s, when antibiotics became available.[31]

In pregnancy

[change source]Pregnant women with UTIs have a higher risk of kidney infections.During pregnancy, high progesterone (a hormone) levels decreased muscle tone of the ureters and bladder. Decreased muscle tone leads to a greater likelihood of reflux, where urine flows back up the ureters and toward the kidneys. Pregnant women do not have an increased risk of asymptomatic bacteriuria, but if bacteriuria are present, pregnant women have a 25-40% risk of a kidney infection.[9] Thus treatment is recommended if urine testing shows signs of an infection—even in the absence of symptoms. Cephalexin or nitrofurantoin are typically used because those medications are generally considered safe in pregnancy.[33] A kidney infection during pregnancy may result in premature birth or pre-eclampsia (a state of high blood pressure, kidney dysfunction, or seizures).[9]

References

[change source]- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 Nicolle LE (2008). "Uncomplicated urinary tract infection in adults including uncomplicated pyelonephritis". Urol Clin North Am. 35 (1): 1–12, v. doi:10.1016/j.ucl.2007.09.004. PMID 18061019.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 Lane, DR (2011 Aug). "Diagnosis and management of urinary tract infection and pyelonephritis". Emergency medicine clinics of North America. 29 (3): 539–52. PMID 21782073.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Colgan, R (2011 Oct 1). "Diagnosis and treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis". American family physician. 84 (7): 771–6. PMID 22010614.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 Salvatore, S (2011 Jun). "Urinary tract infections in women". European journal of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology. 156 (2): 131–6. PMID 21349630.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑ Arellano, Ronald S. Non-vascular interventional radiology of the abdomen. New York: Springer. p. 67. ISBN 9781441977311.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 Bhat, RG (2011 Aug). "Pediatric urinary tract infections". Emergency medicine clinics of North America. 29 (3): 637–53. PMID 21782079.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Woodford, HJ (2011 Feb). "Diagnosis and management of urinary infections in older people". Clinical medicine (London, England). 11 (1): 80–3. PMID 21404794.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑ Amdekar, S (2011 Nov). "Probiotic therapy: immunomodulating approach toward urinary tract infection". Current microbiology. 63 (5): 484–90. PMID 21901556.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 Dielubanza, EJ (2011 Jan). "Urinary tract infections in women". The Medical clinics of North America. 95 (1): 27–41. PMID 21095409.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑ Nicolle LE (2001). "The chronic indwelling catheter and urinary infection in long-term-care facility residents". Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 22 (5): 316–21. doi:10.1086/501908. PMID 11428445.

- ↑ Phipps S, Lim YN, McClinton S, Barry C, Rane A, N'Dow J (2006). Phipps, Simon (ed.). "Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2): CD004374. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004374.pub2. PMID 16625600.

{{cite journal}}:|chapter=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Gould CV, Umscheid CA, Agarwal RK, Kuntz G, Pegues DA (2010). "Guideline for prevention of catheter-associated urinary tract infections 2009". Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 31 (4): 319–26. doi:10.1086/651091. PMID 20156062.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Infectious Disease, Chapter Seven, Urinary Tract Infections from Infectious Disease Section of Microbiology and Immunology On-line. By Charles Bryan MD. University of South Carolina. This page last changed on Wednesday, April 27, 2011

- ↑ Jepson RG, Craig JC (2008). Jepson, Ruth G (ed.). "Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD001321. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001321.pub4. PMID 18253990.

{{cite journal}}:|chapter=ignored (help) - ↑ Rossi, R (2010 Sep). "Overview on cranberry and urinary tract infections in females". Journal of clinical gastroenterology. 44 Suppl 1: S61-2. PMID 20495471.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑ Perrotta, C (2008-04-16). "Oestrogens for preventing recurrent urinary tract infection in postmenopausal women". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (2): CD005131. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005131.pub2. PMID 18425910.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑ Dai, B; Liu, Y; Jia, J; Mei, C (2010). "Long-term antibiotics for the prevention of recurrent urinary tract infection in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Archives of disease in childhood. 95 (7): 499–508. doi:10.1136/adc.2009.173112. PMID 20457696.

- ↑ Salo, J (2011 Nov). "Childhood urinary tract infections as a cause of chronic kidney disease". Pediatrics. 128 (5): 840–7. PMID 21987701.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑ Raynor, MC (2011 Jan). "Urinary infections in men". The Medical clinics of North America. 95 (1): 43–54. PMID 21095410.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑ Leung, David Hui ; edited by Alexander. Approach to internal medicine : a resource book for clinical practice (3rd ed. ed.). New York: Springer. p. 244. ISBN 9781441965042.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help);|first=has generic name (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Kursh, edited by Elroy D. (2000). Office urology. Totowa, N.J.: Humana Press. p. 131. ISBN 9780896037892.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑ Walls, authors, Nathan W. Mick, Jessica Radin Peters, Daniel Egan ; editor, Eric S. Nadel ; advisor, Ron (2006). Blueprints emergency medicine (2nd ed. ed.). Baltimore, Md.: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 152. ISBN 9781405104616.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help);|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Gaines, KK (2004 Jun). "Phenazopyridine hydrochloride: the use and abuse of an old standby for UTI". Urologic nursing. 24 (3): 207–9. PMID 15311491.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ↑ Aronson, edited by Jeffrey K. (2008). Meyler's side effects of analgesics and anti-inflammatory drugs. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science. p. 219. ISBN 9780444532732.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ↑ Glass, [edited by] Jill C. Cash, Cheryl A. Family practice guidelines (2nd ed. ed.). New York: Springer. p. 271. ISBN 9780826118127.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help);|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Zalmanovici Trestioreanu A, Green H, Paul M, Yaphe J, Leibovici L (2010). Zalmanovici Trestioreanu, Anca (ed.). "Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 10 (10): CD007182. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007182.pub2. PMID 20927755.

{{cite journal}}:|chapter=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 Gupta, K (2011 Mar 1). "International clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in women: A 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases". Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 52 (5): e103-20. PMID 21292654.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑ "BestBets: Is a short course of antibiotics better than a long course in the treatment of UTI in children".

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Colgan, R (2011 Sep 1). "Diagnosis and treatment of acute pyelonephritis in women". American family physician. 84 (5): 519–26. PMID 21888302.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑ 30.0 30.1 Brunner & Suddarth's textbook of medical-surgical nursing (12th ed. ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2010. p. 1359. ISBN 9780781785891.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ↑ 31.0 31.1 Al-Achi, Antoine (2008). An introduction to botanical medicines : history, science, uses, and dangers. Westport, Conn.: Praeger Publishers. p. 126. ISBN 9780313350092.

- ↑ Wilson...], [general ed.: Graham (1990). Topley and Wilson's Principles of bacteriology, virology and immunity : in 4 volumes (8. ed. ed.). London: Arnold. p. 198. ISBN 0713145919.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ↑ Guinto VT, De Guia B, Festin MR, Dowswell T (2010). Guinto, Valerie T (ed.). "Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (9): CD007855. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007855.pub2. PMID 20824868.

{{cite journal}}:|chapter=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)