Conspiracy theory

A conspiracy theory is a story that says that a group of people ("conspirators") have agreed ("conspired") to do illegal or evil things and hide them from the public. Conspiracy theories usually have little or no evidence. Many conspiracy theories say that certain historical events were actually caused by such conspirators.

Examples[change | change source]

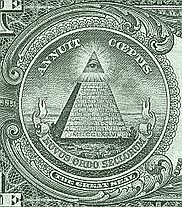

Some conspiracy theories are about the: Apollo moon landing, the 9/11 attacks, the existence of UFO's, the assassination of JFK and the death of Diana, Princess of Wales. Other examples not relating to specific events are the Illuminati, Freemasonry-related conspiracy theories, and chemtrails.

There are different kinds of conspiracy theory. some cases are straightforward. They pretend to explain events to which we do know the real cause, or for which there is no specific cause. We now know all we are ever going to know about the 9/11 attacks and the death of Diana, Princess of Wales. Likewise, that the Earth is round (as opposed to flat) has so much evidence that denying it is simply irrational.

Their growth[change | change source]

There has been a growth in recent years in conspiracy theories proposed on the internet. Conspiracy theories once limited to fringe audiences have become common in mass media, and particularly on the internet. Conspiracy emerged as a cultural phenomenon in the United States of the late 20th and early 21st centuries.[1][2][3][4]

It is worth remembering that conspiracy theorists get paid by websites according to how many viewers they attract. Websites that seem free to the user are paid for by adverts, usually quite harmless, though they may be annoying. The point is that the people who put up the individual articles get paid once the number of viewers is over a certain qualifying number.

David Grimes has calculated that it takes at least three years to expose a conspiracy on the internet, depending on the number of people involved. Many conspiracies would be exposed in between three and four years.[5][6]

References[change | change source]

- ↑ Barkun, Michael 2003. A culture of conspiracy: apocalyptic visions in contemporary America. Berkeley: University of California Press

- ↑ Camp, Gregory S. (1997). Selling fear: conspiracy theories and end-times paranoia. Commish Walsh. ASIN B000J0N8NC.

- ↑ Goldberg, Robert Alan (2001). Enemies within: the culture of conspiracy in modern America. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09000-0. Archived from the original on 17 December 2019.

- ↑ Fenster, Mark (2008). Conspiracy theories: secrecy and power in American culture. University of Minnesota Press; 2nd edition. ISBN 978-0-8166-5494-9.

- ↑ Barajas, Joshua (2016). "How many people does it take to keep a conspiracy alive?". PBS NEWSHOUR. Public Broadcasting Service (PBS). Archived from the original on 13 October 2017. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- ↑ Grimes, David R (2016). "On the viability of conspiratorial beliefs". PLOS ONE. 11 (1): e0147905. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1147905G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0147905. PMC 4728076. PMID 26812482.