Fascism

Fascism is a far-right[1] form of government in which most of the country's power is held by one ruler or a small group, under a single party.[2][3] Fascist governments are usually totalitarian and authoritarian one-party states.[4][5][6] Under fascism, the economy and other parts of society are heavily and closely controlled by the government, usually by using a form of authoritarian corporatism, where companies and workers are supposed to work together under national unity. The government uses violence and police power to arrest, kill or stop anyone it does not think useful.[3][7]

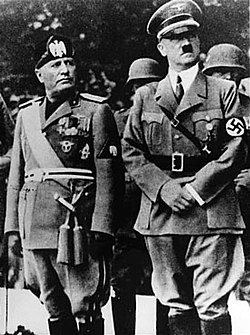

Four large fascist countries were Italy under Benito Mussolini, Nazi Germany under Adolf Hitler, Empire of Japan under Hideki Tojo, and Spain under Francisco Franco.[3]

Mussolini invented fascism in Italy in the late 1910s, and developed it fully in the 1930s. He came to power in late 1922 and introduced a complete dictatorship in the mid-1920s, by eliminating all other parties and changing the electoral law to make sure his Fascist party got the most seats.[8] When Hitler came to power in Germany in the 1930s, he copied Mussolini.[3] Mussolini wrote a political paper, which is called The Doctrine of Fascism in English. He started writing it in 1927, but it was only published in 1932. Most of it was probably written by Giovanni Gentile, an Italian philosopher who joined fascism and became an important influence.

Main ideas[change | change source]

Not all scholars agree on what fascism is. Philosopher Jason Stanley of Yale University says it is "a cult of the leader who promises national restoration in the face of humiliation brought on by supposed communists, Marxists and minorities and immigrants who are supposedly posing a threat to the character and the history of a nation." That is, fascism focuses on one person as leader, fascism says communism is bad, and fascism says that at least one group of people is bad and has caused the nation's problems. This group could be people from other countries or groups of people within the country.[9] Under Hitler's fascist Germany, the government blamed Jews, communists, homosexuals, the disabled, Roma and other people for Germany's problems, arrested those people, and took them to camps to be killed.

In 2003, Laurence W. Britt wrote "14 Defining Characteristics of Fascism":[10]

- 1. Powerful and continuing expressions of nationalism.

- 2. Disdain for the importance of human rights.

- 3. Identification of enemies/scapegoats as a unifying cause.

- 4. The supremacy of the military/avid militarism.

- 5. Rampant sexism.

- 6. A controlled mass media.

- 7. Obsession with national security.

- 8. Religion and ruling elite tied together.

- 9. Power of corporations protected.

- 10. Power of labor suppressed or eliminated.

- 11. Disdain and suppression of intellectuals and the arts.

- 12. Obsession with crime and punishment.

- 13. Rampant cronyism and corruption.

- 14. Fraudulent elections.

- Source:[11]

Name[change | change source]

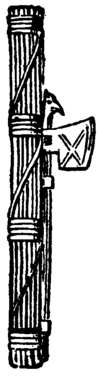

The name fascism comes from the Italian word fascio for bundle. This word comes from the Latin word fasces which was an axe surrounded by a bundle of sticks. In Ancient Rome, leaders carried the fasces as a symbol of their power.[3]

Origins[change | change source]

A journalist named Benito Mussolini invented fascism. He started Italy's fascist party in 1919.[12] He became Italy's prime minister in 1922.[3] He was not elected. His supporters walked into Rome in large numbers, and the king of Italy made him prime minister. Although, officially, the fascist party in Italy was ruled by a "grand council" from 1922 until the end of World War II,[13] Benito Mussolini really had almost all the power in the country.

According to scholar Ruth Ben-Ghiat, Mussolini believed democracy had failed. He had been a Socialist but left the movement because he thought it was not strong enough, and it had refused to join the First World War. He believed democracy failed because of social class and was too weak to stand against Communism. Under fascism, people would focus on the nation and people would not think about social class but instead pull together for the national good.[3]

However, Mussolini also believed that to make fascism work, he and his followers had to remove anything that could distract people from the nation. He also believed he should get to decide who in Italy counted as part of the Italian nation and he should get to throw out or arrest anyone he said did not consider real Italian. He believed it was right to use violence to remove those distractions and those people. Groups of people with weapons would go out into the streets and beat up or even kill people Mussolini did not like.[3]

Mussolini did not allow journalists to write what they wanted.[12]

Mussolini believed that Italy should be made of white people, so he encouraged white women to have more babies and persecuted people who were not white.[3]

Fascism vs other types of totalitarianism[change | change source]

One of the reasons fascism spread in the early 20th century was because the Russian Revolution had just happened and people were afraid of communism. Sometimes landowners and business owners would support fascists because they were afraid of what would happen if the country became communist instead.[3]

In her work, The Origins of Totalitarianism, published in 1951, Hannah Arendt compared National Socialism, Stalinism and Maoism. She does not talk about these regimes being fascist; according to her, they are totalitarian. In 1967, German philosoper Jürgen Habermas warned about a "left-wing fascism" of a protest movement in Germany of the 1960s, commonly known as Ausserparlametarische Opposition, or APO.

Opposition[change | change source]

There is more than one reason why people living in democratic states oppose fascism, but the main reason is that in a Fascist government the individual citizen doesn't always have the option to vote, nor do they have the option to live a lifestyle which may be seen as immoral, useless, and unproductive towards society. If you are not heterosexual (homosexual, cross-dressing, changing genders, etc.) you can be arrested and put on trial.

20th century[change | change source]

The fascist governments in Italy, Germany, and Japan were removed after they lost World War II, but fascism continued as military dictatorships under Salazar in Portugal, Franco in Spain, in some parts of Latin America, Africa, and Asia.

21st century[change | change source]

In the 21st century, fascist political movements exist in many countries.[3]

Related pages[change | change source]

- Anti-fascism

- National Fascist Party

- Nazism

- Right-wing authoritarianism

- Right-wing populism

- Third Reich

- Ultranationalism

References[change | change source]

- ↑ "Overview: fascism". Oxford Reference. Retrieved October 8, 2020.

- ↑ Ben-Ghiat, Ruth (August 10, 2016). "An American Authoritarian". The Atlantic. Retrieved October 10, 2020.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 Waxman, Olivia B. (March 22, 2019). "What to Know About the Origins of Fascism's Brutal Ideology". Time. Retrieved October 8, 2020.

- ↑ Paxton (2004), pp. 32, 45, 173; Nolte (1965) p. 300.

- ↑ Payne, Stanley G. 2005. A history of fascism, 1914 through 1945. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 0-299-14874-2

- ↑ Blamires, Cyprian. 2006. World Fascism: a historical encyclopedia. Volume 1, Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO.

- ↑ "the definition of fascism". www.dictionary.com.

- ↑ Griffin, Roger. 1995. Fascism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 8, 307.

- ↑ Silva, Christiana; James Doubek (September 6, 2020). "Fascism Scholar Says U.S. Is 'Losing Its Democratic Status'". All Things Considered. NPR. Retrieved October 10, 2020.

- ↑ Malmer, Daniel (8 November 2019). "The Long, Complicated History of the "14 Defining Characteristics of Fascism".

- ↑ Britt, Laurence W. (Spring 2003) "Fascism Anyone?" Free Inquiry

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "How Italian dictator Benito Mussolini became the first face of fascism". History Extra. BBC. October 6, 2020. Retrieved October 10, 2020.

- ↑ Fascist Grand Council. Oxford University Press. 2014. ISBN 978-0-19-929567-8. Retrieved 11 March 2014.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)