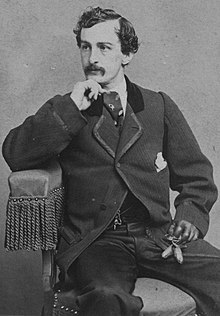

John Wilkes Booth

John Wilkes Booth (May 10, 1838 – April 26, 1865) was an American actor. He is known for killing U.S. president Abraham Lincoln in Washington, D.C. on April 14, 1865. Lincoln died the next morning.

Booth was born in Bel Air, Harford County, Maryland to English immigrant parents. He was a very well-known stage actor. Booth supported the Confederacy during the American Civil War. He was angry with Lincoln for supporting voting rights for former slaves. He also wanted to get Confederate soldiers to keep fighting the war, which was ending.

Booth was chased by United States soldiers and killed at a farm in Virginia twelve days after he shot Lincoln.

Booth's political activity[change | change source]

Booth became politically active in the 1850s. He joined the Know-Nothing Party, a political party that wanted fewer immigrants to come to the United States. Booth strongly supported slavery. In 1859, he joined a Virginia company that helped to capture John Brown after his raid on Harpers Ferry. Booth watched Brown's execution.

During the Civil War, Booth worked as a Confederate secret agent. He met with the heads of the Secret Service, Jacob Thompson and Clement Clay, in Montreal many times.

Failed plots against President Lincoln[change | change source]

In the summer of 1864, Booth began making plans to kidnap President Lincoln. His plan said that Lincoln would be taken south to Richmond, where he would be held until he could be traded for Confederate prisoners of war. Booth recruited friends and Confederate sympathizers to aid him. Eight of these people were later tried for killing Lincoln by a military court designed to prosecute enemies of the United States during wartime. All eight were found guilty; four were executed by hanging. Some people who refused to join Booth, such as actor Samuel Chester, became key government witnesses in the trial.

On March 4, 1865, Booth attended Lincoln's second inauguration as president. Booth appears in some photographs taken that day. On March 15, Booth and most of his conspirators met at a restaurant three blocks from Ford's Theater to plan the kidnapping. Soon after, Booth heard that on March 17, the President would be seeing a play called Still Waters Run Deep at the Campbell Hospital, near Washington, D.C. Booth decided that this was the best time to kidnap him. According to John Surratt, Booth made a plan to intercept Lincoln's carriage on the way to the play. However, President Lincoln changed his plans and decided to speak to the 140th Indiana Regiment and present a captured flag.

Booth's next plan was to kidnap the President at another performance at Ford's Theatre (where Booth had several friends). This plan failed when Booth’s co-conspirators said it would not work.

The assassination of Lincoln[change | change source]

On April 4, the Union Army took over Richmond, the capital city of the Confederacy. Five days later, General Robert E. Lee surrendered Confederate forces to the Union Army. After these two events, Booth decided to kill Lincoln instead of kidnapping him. According to Booth's friend, Louis Weichmann, Booth may have decided to kill the President on April 11. On that day, Booth listened while Lincoln gave a speech supporting voting rights for black Americans. Weichmann, who saw the President's speech with Booth, later said:

- "I had never seen Mr. Lincoln up close and I knew he was a tall man, however nothing could have prepared me for the sight of him. A long shadow did he have. And his arms, when at his sides, touched near his knees. Very professionally he said that there would never be any suffrage based on differences in the way people look. Upon this, Booth turned to the two of us and said, “That means nigger citizenship. Now by God I’ll put him through!”

On April 14, 1865, Booth went to Ford’s Theater in Washington, D.C. to pick up his mail. There he found out that Lincoln and his wife would be seeing a play at the theater that evening. Booth knew the play well. He met with his co-conspirators, and they decided that around 10:15 that evening, they would kill President Lincoln, Vice-president Johnson, Secretary of State William Seward, and possibly General Ulysses S. Grant.

That afternoon, Booth made a hole in a wall at the theater so he could see the President and his guests in their balcony room. There were no guards protecting the balcony room. During the play, Booth quietly entered the room. He knew that at 10:15 pm, the audience would laugh at a line in the play. When the laughter began, Booth fired a pistol at point-blank range into the back of Lincoln's head. Booth escaped by jumping from the balcony onto the stage, where he shouted the triumphant line;Sic semper tyrannis (‘Thus always to tyrants’) to the audience. When he escaped from the box, he broke his leg during the jump, but escaped out the back door and onto his horse.

Lincoln was carried across the street to Petersen House, where he died the next morning. One co-conspirator did attack Secretary of State Seward with a knife the night of the 14th, but Seward survived the attack. The conspirator who planned to attack Vice President Johnson did not follow through with the plot.

Booth fled with an accomplice south through Maryland to Virginia. An army troop caught up with him on April 26. His accomplice surrendered, but Booth refused. He yelled “I will not be taken alive!” He was shot while being captured and later died from his wounds. The bullet struck Booth in the back of the head behind his left ear, passed though his neck, and out into the barn.[1][2] A low scream of pain like that produced by a sudden throttling came from the assassin, and he pitched headlong to the floor.[3] Corbett and the other soldiers would note a sense of poetic, or cosmic, justice in that Lincoln and Booth were each shot around the same spot of the head.[4][5] And the damage to Booth was no less severe than that to Lincoln: the bullet had pierced three vertebrae and partially severed his spinal cord, paralyzing him.[6][7] Their conditions were different, as Mary Clemmer Ames summed it up, "The balls entered the skull of each at nearly the same spot, but the trilling difference made an immeasurable difference in the sufferings of the two. Mr. Lincoln was unconscious of all pain, while his assassin suffered as exquisite agony as if he had been broken on a wheel."[8] A soldier poured water into his mouth, which he immediately spat out, unable to swallow. The bullet wound prevented him from swallowing any of the liquid. In a weak voice, Booth asked for water and Conger and Baker gave it to him.[9] He asked them to roll him over and turn him facedown. Conger thought it a bad idea. Then at least turn me on my side, the assassin pleaded. They did, but Conger saw that the move did not relieve Booth’s suffering. Baker noticed it, too: "He seemed to suffer extreme pain whenever he was moved...and would several times repeat, ‘Kill me.’"[10] At sunrise, Booth remained in agonising pain. His pulse weakening as his breathing became more laboured and irregular. In agony, unable to move his limbs, he asked a soldier to lift his hands before his face and whispered as he gazed at them, "Useless ... Useless." These were his last words. A few minutes later, Booth began gasping for air as his throat continued to swell, then there was a shiver and a gurgle and his body shuddered, before Booth died from asphyxia - he literally choked to death.

Corbett maintained that he didn't intend to kill Booth, but merely wanted to inflict a disabling wound, but either his aim slipped or Booth moved at the moment Corbett pulled the trigger.[9]

References[change | change source]

- ↑ "American Experience | The Assassination of Abraham Lincoln". PBS. Retrieved December 14, 2012.

- ↑ Martelle, Scott (2015). The Madman and the Assassin: The Strange Life of Boston Corbett, the Man Who Killed John Wilkes Booth. Chicago Review Press. p. 103.

- ↑ Terry Alford, Fortune's Fool: The Life of John Wilkes Booth.

- ↑ Goodrich 2005, pp. 227–228

- ↑ "The Death of John Wilkes Booth, 1865". Eyewitness to History/Ibis Communications. Retrieved August 16, 2012.

the bullet struck Booth in the back of the head, about an inch below the spot where his shot had entered the head of Mr. Lincoln.

- ↑ Goodrich, p. 211.

- ↑ Smith, pp. 210–213.

- ↑ Clemmer, Mary. Ten Years in Washington: Life and Scenes in the National Capital as a Woman Sees Them. Cincinnati: Queen City Publishing Company, 1874.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Martelle, Scott (2015). The Madman and the Assassin: The Strange Life of Boston Corbett, the Man Who Killed John Wilkes Booth. Chicago Review Press. p. 104.

- ↑ Swanson, p. 139.