Politics of Germany

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Germany |

| Foreign relations |

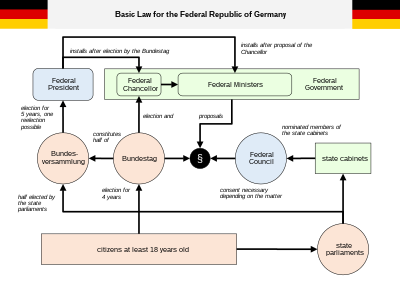

Politics of Germany are based on a federal parliamentary democratic republic. The government is elected by the people in elections where everyone has an equal vote. The constitution is called the Grundgesetz. As well as setting out the rights of the people, it describes the jobs of the President, the Cabinet, the Bundestag, Bundesrat and the Courts.

The President is the head of state. The Federal Chancellor is the head of government, and of the majority group in the legislature (law making body) which is called the Bundestag. Executive power is exercised by the government. The power to make federal law is given to the government and the two parts of parliament, the Bundestag and Bundesrat. The ministers of the government are members of the parliament, and need parliamentary support to stay in power.

From 1949 to 1990, the main political parties were the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) and the Christian Democratic Union (CDU), with its "sister party", the Christian Social Union of Bavaria (CSU). After the reunification of Germany the Green Party and Alliance '90(Bündnis 90/Die Grünen) became more important and was in government between 1999 and 2005. Other important political parties after reunification have been the PDS (Party of Democratic Socialism) which was based on East Germany's Socialist Unity Party of Germany. It joined with The Left Party (Die Linkspartei or Die Linke) of western Germany. In 2007 Die Linke and WASG joined together under the leadership of Oskar Lafontaine

As Germany is a federal country, a lot of the work of government is done by the 16 states (Länder). Power is shared between the national (or federal) government and state governments. The national government cannot abolish the state governments.

Rights and the constitution[change | change source]

The political system is set out in the 1949 constitution, the Grundgesetz (Basic Law), which stayed in effect after 1990's German reunification.

The constitution puts freedom and human rights first. It also splits powers both between the federal and state levels and between the legislative (law-making), executive (government), and judicial (courts) branches. The 1949 Grundgesetz was written to correct the problems with the Weimar Republic's constitution. The Weimar Republic collapsed in 1933 and was replaced by the dictatorship of the Third Reich.

The Federal Courts[change | change source]

The courts of Germany are independent of the government and the lawmakers. Senior judges are appointed by the Bundestag for a fixed term.

Federal executive branch[change | change source]

The Bundeskanzler (Federal Chancellor) heads the Bundesregierung (Federal Cabinet) and thus the executive branch of the federal government. He or she is chosen by and must report to the Bundestag, Germany's parliament. Germany, like the United Kingdom, can thus be said to have a parliamentary system.

Konstruktives Misstrauensvotum[change | change source]

The Chancellor cannot be removed from office during a 4-year term unless the Bundestag has agreed on a successor. This Constructive Vote of No Confidence (German: Konstruktives Misstrauensvotum) is meant to stop what happened in the Weimar Republic. There the government did not have a lot of support in the parliament. The small parties often joined together to vote against the government, but could never stay together and choose a new government.

Except in the periods 1969-72 and 1976-82, when the social democratic party of Chancellor Brandt and Schmidt came in second in the elections, the Chancellor has always been the candidate of the largest party. Usually the largest party is helped by one or smaller more parties to get a majority in the parliament. Between 1969-72 and 1976-82 the smaller parties decided not to help the largest party, but the second biggest party instead.

The Chancellor appoints a Vice-Chancellor (Vizekanzler), who is a member of his cabinet, usually the Foreign Minister. When there is a coalition government (which has, so far, always been the case, except for the period of 1957 to 1961), the Vice-Chancellor usually belongs to the smaller party of the coalition.

The Federal Cabinet[change | change source]

The Chancellor is responsible for policy guidelines. This means he, or she, sets the broad ideas of what the government will do. To help carry out these ideas the Chancellor can change the make-up of the federal ministries whenever they want. For example, in the middle of January 2001, the Federal Ministry of Agriculture was renamed to Ministry of Consumer Protection, Food and Agriculture. This was to help fight the "Mad Cow Disease" BSE problem. At the same time some of the jobs (competencies) of the Ministry of Justice, the Ministry of Economy, and the Ministry of Health were moved to the new Ministry of Consumer Protection.

Reporting to the cabinet is the Civil service of Germany.

The Federal President[change | change source]

The duties of the Bundespräsident (Federal President) are mostly representative and ceremonial; The power of the executive is exercised by the Chancellor.

The President is elected every 5 years on May 23 by the Federal Assembly (Bundesversammlung). The Bundesversammlung only meets to elect the President. Its members are the entire Bundestag and an equal number of state delegates selected especially for this purpose in proportion to election results for the state parliaments. In February 2017, Frank-Walter Steinmeier of the SPD was elected. The reason that the President is not directly elected by the people is to stop him from claiming to be more powerful than the government and the constitution, which happened in the Weimar Republic.

| Office | Name | Party | Since |

|---|---|---|---|

| President | Frank-Walter Steinmeier | --- 1) | 19 March 2017 |

| Chancellor | Olaf Scholz | SPD | 8 December 2021 |

| Other government parties | Green, FDP |

1) Although Mr. Steinmeier has been a member of the SPD, the German Basic Law requests in Article 55 that the Federal President does not hold another office, practice a profession or hold membership of any corporation. Federal President has let his party membership rest dormant and does not belong to a political party during his term of office.

Federal parliament[change | change source]

Germany has a bicameral legislature, which means that the parliament has two houses. The Bundestag (Federal Diet) has at least 598 members, elected for a four-year term. Half of the members (299) are elected in single-seat constituencies according to first-past-the-post. The other 299 members are chosen from statewide party lists.

The total percentage of constituency members and regional list members a party has should equal the percentage of votes that a party gets. This is called proportional representation.

Because Voters vote once for a constituency representative, and a second time for a party Germany is said to have mixed-member proportional representation.

Sometimes a party already has more constituency seats in a land (state) than it should have to keep the percentage of votes and seats equal. The party does not lose seats. Instead, it gets no land seats. This means that the Bundestag sometimes has more than 598 members. In the current parliament, there are 16 overhang seats, giving a total of 614.

A party must get 5% of the national vote or win at least three constituency seats to be represented in the Bundestag. This rule is often called the "five percent hurdle", was made to stop lots of small parties from being in the Bundestag. Small parties were blamed for the problems of the Weimar Republic's Reichstag.

The first Bundestag elections were held in the Federal Republic of Germany ("West Germany") on August 14, 1949. Following reunification, elections for the first all-German Bundestag were held on December 2, 1990. The last election was held on September 24, 2017, the 19th Bundestag met on October 24, 2017.

The Bundesrat (Federal Council) is the representation of the state governments at the federal level. The Bundesrat has 69 members who are delegates of the 16 Bundesländer. Usually, the 16 Ministers President are members, but they do not have to be. The Länder each has from three to six votes in the Bundesrat, depending on the population. Bundesrat members must vote as their state government tell them.

Powers of the legislature[change | change source]

The legislature has powers of exclusive jurisdiction (it can make laws by itself) and concurrent jurisdiction with the Länder (the länder can also make laws). What laws and what type of laws are set out in the Basic Law.

The Bundestag does most lawmaking.

The Bundesrat must concur (agree) to laws about money shared by the federal and state governments and those making more work for the states. Often this means that the Bundesrat often needs to agree to a law because federal laws are often carried out by state or local agencies.

Since the political make-up of the Bundesrat is often different from that of the Bundestag, the Bundesrat is often the place for opposition parties to put their point of view, rather than for the states to look after their interests, as the constitution intended.

To limit, members of the Bundestag and the Bundesrat form a Vermittlungsauschuss which is a joint committee to try to reach an agreement when the two chambers can not agree on a certain piece of legislation.

Political parties and elections[change | change source]

- For other political parties see List of political parties in Germany.

Bundestag[change | change source]

The following parties are represented in the German Bundestag since the federal elections of 2017:[1]

Total 709 seats.

The Pirate Party Germany and the National Democratic Party of Germany (NPD) got no seats.

Bundesrat[change | change source]

The Federal Council is composed by representatives of the State governments.

Political profile of the German Bundesrat as of July 2017:

| Political profile of State governments |

Seats |

|---|---|

| CDU-FDP | 6 |

| CDU-FDP-Greens | 4 |

| CDU-Greens | 11 |

| CDU-Greens-SPD | 4 |

| CDU-SPD | 10 |

| CSU | 6 |

| FDP-Greens-SPD | 4 |

| Greens-Linke-SPD | 8 |

| Greens-SPD | 12 |

| Linke-SPD | 4 |

| Total | 69 |

- ->See also: Bundesrat - States.

Judicial branch[change | change source]

Germany has had a court system that was free of government control for longer than it has had democracy.

This means that the courts have traditionally been strong, and almost all state actions are subject to judicial review (being looked at by the court).

Organization[change | change source]

There is the "ordinary" courts system that handles civil and criminal cases

This has four levels

- Amtsgericht - local courts

- Landesgericht - state courts

- Oberlandesgericht - state appeals courts

- Bundesgerichtshof - the federal supreme criminal and civil court

There is also a system of specialist courts, that deals with certain areas of the law. These generally have a state court and state appeals court before coming to the federal supreme court for that area of law. The other federal supreme courts are

- Bundesfinanzhof - tax affairs

- Bundesarbeitsgericht - Labour law

- Bundessozialgericht - Social security law

- Bundesverwaltungsgericht - Administrative law. This includes government regulations not covered by one of the other three specialist courts.

Unlike the United States, all courts are state courts, except for the top-level supreme courts.

Bundesverfassungsgericht[change | change source]

Germany also has another supreme court, the Bundesverfassungsgericht Federal Constitutional Court. The Grundgesetz says that every person may complain to the Federal Constitutional Court when his or her constitutional rights, especially human rights, have been violated by the government or one of its agencies and after he or she has gone through the ordinary court system.

The Bundesverfassungsgericht hears complaints about laws passed by the legislative branch, court decisions, or acts of the administration.

Usually, only a small percentage of these constitutional complaints, called (Verfassungsbeschwerden) are successful. Even so, the Court has often angered both the government and the lawmakers. The judges even say that they do not care about the reactions of the government, the Bundestag, or public opinion or about the cost of one of the court's decisions. All that matters is the constitution.

The Bundesverfassungsgericht is very high popular with ordinary people because it protects them from government wrongdoing.

Only the Constitutional Court can handle some types of cases, including arguments between government bodies about their constitutional powers.

Only the Constitutional Court has the power to ban political parties for being unconstitutional. However so far the Constitutional court has only used this power twice, outlawing the KPD (Communist Party of Germany) and the SRP (Socialist Reich Party, a successor to the NSDAP) because both parties ideas went against the constitution.

Recent political issues[change | change source]

"Red-Green" vs. Conservative-led coalitions[change | change source]

In the 1998 election the SPD said they wanted to reduce high unemployment rates and said new people were needed in government after 16 years of Helmut Kohl's government.

Gerhard Schröder said he was a centrist "Third Way" candidate like Britain's Tony Blair and America's Bill Clinton.

The CDU/CSU said people should look at how well off they were because of Kohl's government, and that the CDU/CSU had experience in foreign policy.

But the Kohl government was hurt at the polls by slower growth in the east in the previous two years, which meant the gap between east and west widened as the west got richer and the east did not.

The final seat count was enough to allow a "red-green" coalition of the SPD with Alliance '90/The Greens (Bündnis '90/Die Grünen), bringing the Greens into a national government for the first time.

The first months of the new government had policy disputes between the moderate and traditional left wings of the SPD, and some voters got fed up. The first state election after the federal election was held in Hesse in February 1999. The CDU increased its vote by 3.5%. The CDU became the largest party and replaced an SPD/Green coalition with a CDU/FDP coalition. The result was seen in part as a referendum on the federal government's ideas for a new citizenship law, which would have made it easier for long-time foreign residents to become German citizens, and also to keep their original citizenship as well.

In March 1999, SPD chairman and Minister of Finance Oskar Lafontaine, who represented a more traditional social democratic position, resigned from all offices after losing a party-internal power struggle against Schröder.

In state elections in 2000 and 2001, the respective SPD- or CDU-led coalition governments were re-elected into power.

The next election for the Bundestag was September 22, 2002. Gerhard Schröder led the coalition of SPD and Greens to an 11-seat victory over the CDU/CSU headed by Edmund Stoiber (CSU). Two factors are generally cited that enabled Schröder to win the elections despite poor approval ratings a few months before: good handling of the 2002 European floods and firm opposition to the USA's 2003 invasion of Iraq.

The coalition treaty for the second red-green coalition was signed on October 16, 2002. There were a lot of new ministers.

Conservative comeback[change | change source]

In February 2003, elections took place in the states of Hesse and Lower Saxony, was won by the conservatives. In Hesse, the CDU minister president Roland Koch was re-elected, with his party CDU gaining enough seats to govern without the former coalition partner FDP.

In Lower Saxony, the former SPD minister president Sigmar Gabriel lost the elections, leading to a CDU/FDP-government headed by new minister president Christian Wulff (CDU). The protest against the Iraq war changed this situation a bit, favoring SPD and Greens.

The latest election in the state of Bavaria led to a landslide victory of the conservatives, gaining not just the majority (as usual), but two thirds of parliamentary seats.

In April 2003, chancellor Schröder announced massive labor market reforms, called Agenda 2010. This included a shakeup of the system of German job offices (Arbeitsamt), cuts in unemployment benefits and subsidies for unemployed persons who start their own businesses. These changes are commonly known by the name of the chairman of the commission which conceived them as Hartz I - Hartz IV. Although these reforms have sparked massive protests they are now credited with being in part responsible for the economic upswing and the fall of unemployment figures in Germany in the years 2006/7.

The European elections on June 13, 2004, brought a staggering defeat for the Social Democrats, who polled only slightly more than 21%, the lowest election result for the SPD in a nationwide election since the Second World War. Liberals, Greens, conservatives, and the far left were the winners of the European election in Germany, because voters were disillusioned by high unemployment and cuts in social security, while the governing SPD party seems to be concerned with quarrels between its members and gave no clear direction. Many observers believe that this election marked the beginning of the end of the Schröder government.

Rise of the Right[change | change source]

In September 2004, elections were held in the states of Saarland, Brandenburg and Saxony. In the Saarland, the governing CDU was able to remain in power and gained one additional seat in the parliament and the SPD lost seven seats, while the Liberals and Greens re-entered the state parliament. The far-right National Democratic Party, which had never got more than 1 or 2% of the vote, received about 4%, although it failed to earn a seat in the state parliament (a party must obtain at least 5% of the vote to achieve state parliamentary representation).

Two weeks later, elections were held in the eastern states of Brandenburg and Saxony: once again, overall, the ruling parties lost votes and although they remained in power, the right to far-right parties made the big leaps. In Brandenburg, the Deutsche Volksunion (DVU) re-entered the state parliament after winning 6.1% of the vote. In Saxony, the NPD entered a non-competition agreement with the DVU and obtained 9.2% of the vote, thus winning seats in the state parliament. Due to their losses at the ballots, the ruling CDU of Saxony was forced to form a coalition with the SPD. The rise of the right to far-right worries the ruling political parties.

German federal election 2005[change | change source]

On May 22, 2005, as predicted the SPD was defeated in its former heartland, North Rhine-Westphalia. Half an hour after the election results, the SPD chairman Franz Müntefering announced that the chancellor would clear the way for premature federal elections by deliberately losing a vote of confidence.

This took everyone by surprise, especially because the SPD was below 25% in polls at the time. On the following Monday, the CDU announced Angela Merkel as a conservative candidate for chancellorship.

Whereas in May and June 2005 victory of the conservatives seemed highly likely, with some polls giving them an absolute majority, this changed shortly before the election on September 18, 2005, especially after the conservatives introduced Paul Kirchhof as potential minister of the treasury, and after a TV duel between Merkel and Schröder where many considered Schröder to have performed better.

New for the 2005 election was the alliance between the newly formed Electoral Alternative for Labour and Social Justice (WASG) and the PDS, planning to join into a common party (see Left Party.PDS). With the former SPD chairman Oskar Lafontaine for the WASG and Gregor Gysi for the PDS as prominent figures, this alliance soon found interest in the media and in the population. Polls in July saw them as high as 12%.

After success in the state election for Saxony, the alliance between the far right parties National Democratic Party and Deutsche Volksunion (DVU), which planned to leapfrog the "five-percent hurdle" on a common party ticket was another media issue.

The election results of September 18, 2005, were surprising. They were very different from the polls of the previous weeks. The conservatives lost votes compared to 2002, reaching only 35%, and failed to get a majority for a "black-yellow" government of CDU/CSU and liberal FDP. The FDP polled 10% of the votes, one of their best results ever. But the red-green coalition also failed to get a majority, with the SPD losing votes, but polling 34% and the greens staying at 8%. The left party alliance reached 8.7% and entered the German Parliament, whereas the NPD only got 1.6%.

The most likely outcome of coalition talks was a so-called "grand coalition" between the conservatives (CDU/CSU) and the social democrats (SPD), with the three smaller parties (liberals, greens, and the left) in the opposition. Other possible coalitions include a "traffic light coalition" between SPD, FDP, and Greens and a "Jamaica coalition" between CDU/CSU, FDP, and Greens. Coalitions involving the Left Party were ruled out by all parties (including the Left Party itself), although the combination of one of the major parties and any two small parties would mathematically have a majority. Of these combinations, only a red-red-green coalition is politically even imaginable. Both Gerhard Schröder and Angela Merkel announced that they had won the election and should become the next chancellor.

On October 10, talks were held between Franz Müntefering, the SPD chairman, Gerhard Schröder, Angela Merkel, and Edmund Stoiber, the CSU chairman. In the afternoon it was announced that the CDU/CSU and SPD would begin formal coalition negotiations with the aim of a Grand Coalition with Angela Merkel as the next German chancellor.

Angela Merkel is the first woman, the first East German and the first scientist to be chancellor as well as the youngest German chancellor ever. On November 22, 2005, Angela Merkel was sworn in by president Horst Köhler for the office of Bundeskanzlerin.

References[change | change source]

- ↑ "Deutscher Bundestag - Fraktionen". Deutscher Bundestag (in German). Archived from the original on 2017-01-29. Retrieved 2020-06-20.

Related pages[change | change source]

- Political culture of Germany

- German emergency legislature

- German federal election, 2017

- List of political parties in Germany