User:TrueCRaysball/Ted Williams

| Ted Williams | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Left fielder | |||

| Born: August 30, 1918 San Diego, California | |||

| Died: July 5, 2002 (aged 83) Inverness, Florida | |||

| |||

| debut | |||

| April 20, 1939, for the Boston Red Sox | |||

| Last appearance | |||

| September 28, 1960, for the Boston Red Sox | |||

| Career statistics | |||

| Batting average | .344 | ||

| Home runs | 521 | ||

| Hits | 2,654 | ||

| Runs batted in | 1,839 | ||

| Teams | |||

|

As player As manager | |||

| Career highlights and awards | |||

| [[{{{hoflink}}}|Member of the {{{hoftype}}}]] | |||

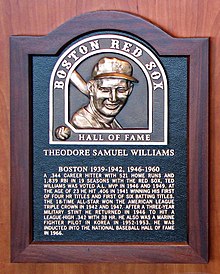

| Induction | 1966 | ||

| Vote | 93.38% (first ballot) | ||

Theodore Samuel "Ted" Williams (August 30, 1918 – July 5, 2002) was an American professional baseball player and manager. He played his entire 21-year Major League Baseball career as the left fielder for the Boston Red Sox (1939–1942 and 1946–1960). Williams was a two-time American League Most Valuable Player (MVP) winner, led the league in batting six times, and won the Triple Crown twice. A nineteen-time All-Star, he had a career batting average of .344, with 521 home runs, and was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1966.[1] Williams got a hit only 34 per cent of the time. He got on base an astounding 48 per cent of the time.[2]

Williams was the last player in Major League Baseball to bat over .400 in a single season (.406 in 1941). Williams holds the highest career batting average of anyone with 500 or more home runs. His best year was 1941, when he hit .406 with 37 HR, 120 RBI, and 135 runs scored. His .551 OBP set a record that stood for 61 years. Nicknamed "The Kid", "The Splendid Splinter", "Teddy Ballgame", "The Thumper" and, because of his hitting prowess, "The Greatest Hitter Who Ever Lived", Williams's career was twice put on hold by service as a U.S. Marine Corps fighter-bomber pilot.[3] An avid sport fisherman, he hosted a television program about fishing, and he was inducted into the IGFA Fishing Hall of Fame.[4]

Early life[change | change source]

Ted Williams was born in San Diego[5] as Teddy Samuel Williams, named after his father, Samuel Stuart Williams, and President Teddy Roosevelt,[6] although Williams claimed that his middle name stemmed from one of his mother's brothers (in truth, her dead brother was Daniel) who had been killed in World War I.[7] At some point, Williams changed the name on his birth certificate to Theodore.[6] The older of his brother, Danny,[8] his father was a soldier, sheriff, and photographer from New York,[9] while his mother, May Venzor, from El Paso, Texas, was an evangelist and lifelong soldier in the Salvation Army.[6] Williams resented his mother's long hours work in the Salvation Army,[10] and Williams and his brother cringed whenever they were brought by her to the Army's street-corner revivals.[11]

Williams's paternal ancestors were a mix of Welsh and Irish, and his maternal ancestors were of Mexican and French descent.[8][12][13][14] The Mexican side of Williams's family was quite diverse, having Spanish (Basque), Russian, and American Indian roots.[15] Of his Mexican ancestry he said that "If I had had my mother's name, there is no doubt I would have run into problems in those days, [considering] the prejudices people had in Southern California".[14]

Williams lived in San Diego's North Park neighborhood (4121 Utah Street),[16] and was taught how to throw a baseball by his uncle Saul Venzor, a former semi-pro baseball player and one of his mother's four brothers who had previously pitched against Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, and Joe Gordon in an exhibition game, at the age of eight.[17][18] As a child, Williams' heroes were Pepper Martin of the St. Louis Cardinals and Bill Terry of the New York Giants.[19] Williams graduated from Herbert Hoover High School in San Diego, where he played baseball as a hitter-pitcher and was the star of the team.[20] Though he had offers from the St. Louis Cardinals and the New York Yankees while he was still in high school,[21] his mother thought he was too young to leave home, so he signed up with the local minor league club, the San Diego Padres.[22]

Baseball career[change | change source]

Throughout his career, Williams stated his goal was to have people point to Williams and remark, "There goes Ted Williams, the greatest hitter who ever lived."[23]

While in the Pacific Coast League in 1936, Williams met future teammates and friends Dom DiMaggio and Bobby Doerr, who were on the Pacific Coast League's San Francisco Seals.[24] Williams played back-up on the team behind DiMaggio's brother Vince DiMaggio and Ivey Shiver. When Shiver announced he was quitting to become a football coach at the University of Georgia, the job, by default, was open for Williams.[25] Williams posted a .271 batting average on 107 at-bats in 42 games for the Padres in 1936.[25] Unknown to Williams, he had caught the eye of the Boston Red Sox's general manager, Eddie Collins, while Collins was scouting Bobby Doerr and the shortstop George Myatt in August 1936.[25][26] Collins later explained, "It wasn't hard to find Ted Williams. He stood out like a brown cow in a field of white cows."[25] In the 1937 season, after graduating Hoover High in the winter, Williams finally broke into the line-up on June 22, when he hit an inside-the-park home run to help the Padres win 3 - 2. The Padres ended up winning the PCL title, while Williams ended up hitting .291 with 23 home runs.[25] Meanwhile, Collins kept in touch with Padres general manager Bill Lane, calling him two times throughout the season. In December 1937, during the winter meetings, the deal was made between Lane and Collins, sending Williams to the Boston Red Sox and giving Lane $35,000 and two major leaguers, Dom D'Allessandro and Al Niemiec, and two other minor leaguers.[27][28]

In 1938, the nineteen-year-old Williams was ten days late to spring training camp in Sarasota, Florida, because of a flood in California blocking the railroads. Williams had to borrow $200 from a bank to make the trip from San Diego to Sarasota.[29] Also during spring training Williams was nicknamed "The Kid" by Red Sox equipment manager Johnny Orlando, who after Williams arrived to Sarasota for the first time, said, "'The Kid' has arrived". Orlando still called Williams "The Kid" twenty years later,[29] while the nickname stuck with Williams the rest of his life.[30] Williams remained in major league spring training for about a week.[29] Williams was then sent to the Double-A-league Minneapolis Millers.[31] While in the training camp of the Millers camp for the springtime, Williams met Rogers Hornsby, who had hit over .400 three times, including a .424 average in 1924,[32] who was a coach for the Millers for the spring.[32] Hornsby told Williams useful advice, including to "get a good pitch to hit".[31] Talking with the game's greats would become a pattern for Williams, who talked with Hugh Duffy who hit .438 in 1894, Bill Terry who hit .401 in 1930, and Ty Cobb against whom he would argue that a batter (baseball) should hit up on the ball, opposed to Cobb's view that a batter should hit down on the ball.[33]

While in Minnesota, Williams quickly became the team's star.[34] He collected his first hit on the Millers' first game of the season, and his first and second home runs on his third game. Both were inside-the-park home runs, while the second traveled an estimated five-hundred feet on the fly to a five-hundred and twelve foot center field fence.[34] Williams later had a twenty-two game hitting streak that lasted from Memorial Day to mid-June.[34] While the Millers ended up sixth place in an eight-team race,[34] Williams ended up hitting .366 with 46 home runs and 142 RBIs while receiving the American Association's Triple Crown and finishing second in the voting for Most Valuable Player voting.[35]

1939 - 40[change | change source]

Williams came to spring training three days late in 1939, thanks to Williams driving from California to Florida and respiratory problems, the latter of which would plague Williams for the rest of his career.[36] In the winter, the Red Sox traded right fielder Ben Chapman to the Cleveland Indians to make room for Williams on the roster, with Williams inheriting Chapman's number 9 on his uniform opposed to Williams' number 5 in the previous spring training, even though Chapman had hit .340 in the previous season,[37][38] which led Boston Globe sports journalist Gerry Moore to quip, "Not since Joe DiMaggio broke in with the Yankees by "five for five" in St. Petersberg in 1936 has any baseball rookie received the nationwide publicity that has been accorded this spring to Theodore Francis [sic] Williams".[36] Williams made his major league debut against the New York Yankees on April 20,[39] going 1-for-4 against Yankee pitcher Red Ruffing. This was the only game in which featured both Williams and Lou Gehrig playing against one another.[40] In his first series at Fenway Park, Williams batted a double, a home run, and a triple, the first two against Cotton Pippen, who gave Williams his first strikeout as a professional while Williams had been in San Diego.[41] By July, Williams was hitting just .280, but leading the league in RBIs.[41] Johnny Orlando, now Williams' friend, then gave Williams a quick pep talk, telling Williams that he should hit .335 with 35 home runs and he would drive in 150 runs. Williams said he would buy Orlando a Cadillac if this all came true.[42] Williams ended up hitting .327 with 31 home runs and 145 RBIs,[39] leading the league in the latter category, the first rookie to lead the league in runs batted in.[43] and finishing fourth in MVP voting.[44] Even though there was not a Rookie of the Year award yet in 1939, Babe Ruth declared Williams to be the Rookie of the Year, to which Williams later said was "good enough for me".[45]

Williams pay doubled in 1940, going from $5,000 to $10,000.[46] With the addition of a new bullpen in right field of Fenway Park, which reduced the distance from home plate from 400 feet to 380 feet, the bullpen was nicknamed "Williamsburg", because the new addition was "obviously designed for Williams".[47] Williams was then switched from right field to left field, as there would be less sun in his eyes, and it would give Dominic DiMaggio a chance to play. Finally, Williams was flip-flopped in the order with the great slugger Jimmie Foxx, with the idea that Williams would get more pitches to hit.[47] Pitchers, though, were not afraid to walk him to get to the 33-year-old Foxx, and after that the 34-year-old Joe Cronin, the player-manager.[48] Williams also made his first of sixteen All-Star Game appearances[49] in 1940, going 0-for-2.[50] Although Williams hit .344, his power and runs batted in were down from the previous season, with 23 home runs and 113 RBIs.[39] Williams also caused a controversy in mid-August when he called his salary "peanuts", along with saying he hated the city of Boston and reporters, leading reporters to lash back at him, saying that he should be traded.[51] Williams said that the "only real fun" he had in 1940 was being able to pitch once on August 24, when he pitched the last two innings in a 12 - 1 loss to the Detroit Tigers, allowing one earned run on three hits, while striking out one batter, Rudy York.[52][53]

1941[change | change source]

In the second week of spring training in 1941, Williams broke a bone in his right ankle, limiting him to pinch hitting for the first two weeks of the season.[54] Bobby Doerr later claimed that the injury would be the foundation of Williams's season, as it forced him to put less pressure on his right foot for the rest of the season.[55] Against the Chicago White Sox on May 7, in extra innings, Williams told the Red Sox pitcher, Charlie Wagner, to hold the White Sox, since he was going to hit a home run. In the 11th inning, Williams's prediction came true, as he hit a 600-footer to help the Red Sox win. The home run is still considered to be the longest home run ever hit in the old Comiskey Park, some saying that it went 600 feet (183 meters).[56] Williams's average slowly climbed in the first half of May, and on May 15, he started a 22-game hitting streak. From May 17 to June 1, Williams batted .536, with his season average going above .400 on May 25 and then continuing up to .430.[57] By the All-Star break, Williams was hitting .405 with 62 RBIs and 16 home runs.[58]

In the 1941 All-Star Game, Williams batted fourth behind Joe DiMaggio, who at that time had broken the consecutive hitting streak record and already had a 48-consecutive-game hitting streak by the All-Star break.[59] In the fourth inning, Williams doubled to drive in a run,[60] but the National League was winning 5 - 2 in the eighth inning, and Williams struck out in the bottom half of the inning in the middle of a rally by the American League team.[59] In the ninth inning, with the American League trailing 5 - 3, Ken Keltner got an infield single, Joe Gordon singled, and then Cecil Travis walked to fill the bases.[60] After that, Joe DiMaggio grounded to the infield, and in attempting to carry out a double play, Billy Herman was distracted by Travis as Travis slid into second base, and the throw to first base was wide, with Keltner scoring, making the score 5-4.[60] With runners on first base and third base, Williams stepped to the plate. With a two-ball-and-one-strike count, Williams swung with his eyes closed and hit a home run,[60] making the American League walk-off to win 7 - 5.[61] Williams later said that the moment "remains to this day the most thrilling hit of my life".[62]

In late August, Williams was hitting .402.[62] Williams said that "just about everybody was rooting for me" to hit .400 in the season, including Yankee fans, who gave pitcher Lefty Gomez a "hell of a boo" after walking Williams with the bases loaded after Williams had gotten three straight hits one game in September.[63] In mid-September, Williams was hitting .413, but dropped a point a game from then on.[62] Before the game on September 28, Williams was batting .39955, which would have been rounded up to a .400 average.[62] Williams, who had the chance to sit out the final, decided to play a doubleheader against the Philadelphia Athletics. Williams explained that he didn't really deserve the .400 average if he did sit out).[64] Williams went 6-for-8 on the day, finishing the baseball season at .406.[65] (The present-day baseball sacrifice fly rule was not in effect in 1941; had it been, Williams would have hit .416.) Portions of the 10,268 people in the crowd ran out on the field to surround Williams after the game, forcing him to grab his hat in fear of its getting stolen, and he was helped into the clubhouse by his teammates.[66] Along with his .406 average, Williams also hit 37 home runs and had 120 RBIs.[39] Williams's baseball season of 1941 is often considered to be the best offensive season of all time. The .406 batting average was Williams's first of six batting championships, and it is still the highest single-season batting average in Red Sox history and the highest batting average in the major leagues since 1924. Williams's on-base percentage of .553 and slugging percentage of .735 that season are both also the highest single-season averages in Red Sox history. The .553 OBP stood as a major league record until it was broken by Barry Bonds in 2002 and his .735 slugging percentage was highest mark in the major leagues between 1932 and 1994. His OPS of 1.287 that year, a Red Sox record, was the highest in the major leagues between 1923 and 2001. Williams led the league with 135 runs scored and 37 home runs, and he finished third with 335 total bases, the most home runs, runs scored, and total bases by a Red Sox player since Jimmie Foxx's in 1938.[67] Williams placed second in MVP voting, with Joe DiMaggio winning with 291 votes to 254 votes[68] on the strength of his record-breaking 56-game hitting streak and large number of RBIs.[65]

On December 7, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, forcing the United States into World War II a day later.[69][70]

1942 and Baseball during the War[change | change source]

In January 1942, Williams was drafted into the military, being put into Class 1-A. A friend of Williams suggested that Williams see the advisor of the Governor's Selective Service Appeal Agent, since Williams was the sole support of his mother, ever since his parents had divorced in 1939. The agent agreed that Williams should not have been placed in Class 1-A, and said Williams should be reclassified to Class 3-A.[69] The attorney took the case to the Appeals Board and the board rejected the case. Angry, the attorney took the case to the Presidential Board. Williams was reclassified to 3-A ten days later.[71] Afterwards, the public reaction was extremely negative,[72] and Quaker Oats stopped sponsoring Williams, and Williams, who had previously had eaten them "all the time", never had "eaten one since".[71]

Despite the trouble with the draft board, Williams had a new salary of $30,000 in 1942.[71] In the season, Williams won the Triple Crown,[65] with a .356 batting average, 36 home runs, and 137 RBIs.[39] On May 21, Williams also hit his 100th career home run.[73] He was the third Red Sox player to hit 100 home runs with the team, following his teammates Jimmie Foxx and Joe Cronin.[74] Despite winning the Triple Crown, Williams came in second in the MVP voting to Joe Gordon of the Yankees. Williams felt that he should have gotten a "little more consideration" because of him winning the Triple Crown, and he thought that that "the reason I didn't get more consideration was because of the trouble I had with the draft [boards]".[65]

After going into the U.S. Marine Corps as an aviator at the end of 1942, Williams also played on the baseball team in Chapel Hill, North Carolina along with his Red Sox teammate Johnny Pesky in pre-flight training, after eight weeks in Amherst, Massachusetts and the Civilian Pilot Training Course.[75] While Williams played on the baseball team, he was sent back to Fenway Park on July 13, 1943 to play on an All-Star team managed by Babe Ruth. The newspapers reported that Babe Ruth said when finally meeting Williams, "Hiya, kid. You remind me a lot of myself. I love to hit. You're one of the most natural ballplayers I've ever seen. And if my record is broken, I hope you're the one to do it".[76] Williams later said he was "flabbergasted" by the incident, as "after all, it was Babe Ruth".[76] In the game, Williams hit a 425-foot home run to help give the American League All-Stars a 9-8 win.[77]

On August 18, 1945, twelve days after an atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Williams was sent to Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. While in Pearl Harbor, Williams played baseball in the Army League. Also in that league were Joe DiMaggio, Joe Gordon, and Stan Musial. The Service World Series with the Army versus the Navy attracted crowds of 40,000 for each game. The players said it was even better than the actual World Series being played between the Detroit Tigers and Chicago Cubs that year.[78] Williams was discharged by the Marine Corps in January 1946, in time to begin preparations for the upcoming pro baseball season.[79][80]

1946–1947[change | change source]

Joining the Red Sox again in 1946, Williams signed a $37,500 contract.[81] On July 14, after Williams hit three home runs and eight RBIs in the first game of a doubleheader, Lou Boudreau, inspired by Williams' consistent pull hitting to right field, created what would later be known as the Boudreau shift (also Williams shift) against Williams, having only one player on the left side of second base (the left fielder). Ignoring the shift, Williams walked twice and grounded out to second base.[82] Also during 1946, the All-Star Game was held in Fenway Park. In the game, Williams homered in the fourth inning against Kirby Higbe, singled in a run in the fifth inning, singled in the seventh inning, and hit a three-run home run against Rip Sewell's notorious "eephus pitch" in the eighth inning[83] to help the American League win 12 - 0.[84]

For the 1946 baseball season, Williams hit .342 with 38 home runs and 123 RBIs,[39] helping the Red Sox win the pennant on September 13, hitting the only inside-the-park home run in his Major League career in a 1 - 0 win against Cleveland.[85] Williams ran away as the winner in the MVP voting.[86] During an exhibition game in Fenway Park against an All-Star team during early October, Williams was hit on the elbow by a curveball by the Washington Senators' pitcher Mickey Haefner. Williams was immediately taken out of the game, and X-rays of his arm showed no damage, but his arm was "swelled up like a boiled egg", according to Williams.[87] Williams could not swing a bat again until four days later, one day before the World Series, when he reported the arm as "sore".[87] During the series, Williams batted .200, going 5-for-25 with no home runs and just one RBI. The Red Sox lost in seven games,[88] with Williams going 0-for-4 in the last game.[89] Fifty years later when asked what one thing he would have done different in his life, Williams replied, "I'd have done better in the '46 World Series. God, I would".[87] The 1946 World Series was the only World Series Williams ever appeared in.[90]

In the off-season between the 1946 and 1947 season, Williams was offered a three-year, $300,000 dollar contract to play for the Mexican League, which Williams declined. Williams later signed a $70,000 contract in 1947.[91] Williams was also almost traded for Joe DiMaggio in 1947. In late April, Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey and Yankees owner Dan Topping agreed to swap the players, but a day later canceled the deal when Yawkey requested that Yogi Berra come with DiMaggio.[92] In May, Williams was hitting .337.[93] Williams also won the Triple Crown in 1947, but lost the MVP award to Joe DiMaggio, with 201 votes compared to DiMaggio's 202 votes. One writer (whom Williams thought was Mel Webb, who Williams called a "grouchy old guy",[94] although the identity of the writer remains unknown) completely left Williams off his ballot, who would have tied DiMaggio or won if one writer who had voted Williams as second had voted him first.[95]

Through 2011, he was one of seven major leaguers to have had at least four 30-homer, 100-RBI seasons in their first five years, along with Chuck Klein, Joe DiMaggio, Ralph Kiner, Mark Teixeira, Albert Pujols, and Ryan Braun.[96]

1948[change | change source]

In 1948, under their new manager Joe McCarthy,[97] Williams hit a league-leading .369 with 25 home runs and 127 RBIs,[39] and was third in MVP voting.[98] On April 29, Williams hit his 200th career home run. He became just the second player to hit 200 home runs in a Red Sox uniform, joining his former teammate Jimmie Foxx.[99] On October 2, against the Yankees, Williams hit his 222nd career home run, tying Foxx for the Red Sox all-time record.[100] In the Red Sox final two games against the Yankees to force a one-game playoff against the Cleveland Indians, Williams got on base eight times out of ten plate appearances.[97] In the playoff, Williams went 1-for-4,[101] with the Red Sox losing 8–3 due to McCarthy's decision to start Denny Galehouse over southpaw Mel Parnell.[102]

1949[change | change source]

In 1949, Williams got a new salary of $100,000 ($1,139,000 in current dollar terms).[95] He hit .343 (losing the AL batting title by just .0002 to the Tigers' George Kell, thus missing the Triple Crown that year), hitting 43 home runs, his career high, and driving in 159 runs, tied for highest in the league, helping him win the MVP trophy.[39][103] On April 28, Williams hit his 223rd career home run, breaking the record for most home runs in a Red Sox uniform, passing Jimmie Foxx.[104] Williams is still the Red Sox career homerun leader.[99] However, despite being ahead of the Yankees by one game right before the series,[97] the Red Sox lost both games they had to play against the Yankees.[105] The Yankees won the first of what would be five straight World Series titles in 1949.[106] For the rest of Williams' career, the Yankees won eight pennants and five World Series titles, while the Red Sox never finished better than third place.[106]

1950[change | change source]

In 1950, Williams was playing in his eighth All-Star Game. In the first inning, Williams caught a line drive by Ralph Kiner, slamming into the Comiskey Park scoreboard and breaking his left arm.[49] Williams played the rest of the game, and he even singled in a run to give the American League the lead in the eighth inning, but by that time Williams' arm was a "balloon" and he was in great pain, so he left the game.[107] Both of the doctors who X-rayed Williams held little hope for a full recovery. The doctors operated on Williams for two hours.[108] When Williams took his cast off, he could only extend the arm to within four inches of his right arm.[109] Williams only played 89 games in 1950.[39] After the baseball season, Williams's elbow hurt so much he considered retirement, since he thought he would never be able to hit again. Tom Yawkey, the Red Sox owner, then sent Jack Fadden to Williams's Florida home to talk to Williams. Williams later thanked Fadden for saving his career.[110]

1951[change | change source]

In 1951, Williams "struggled" to hit .318, with his elbow still hurting.[111] Williams also played in 148 games, sixty more than Williams had played the previous season, 30 home runs, two more than he had hit in 1950, and 126 RBIs, twenty-nine more than 1950.[39][111] Despite his lower-than-usual production at bat, Williams made the All-Star team.[50] On May 15, 1951, Williams became the 11th player in major league history to hit 300 career home runs. On May 21, Williams passed Chuck Klein for 10th place, on May 25 Williams passed Rogers Hornsby for 9th place, and on July 5 Williams passed Al Simmons for 8th place all-time in career home runs.[112][113] After the season, manager Steve O'Neill was fired, with Lou Boudreau replacing him. Boudreau's first announcement as manager was that all Red Sox players were "expendable", including Williams.[111]

1952 - 55[change | change source]

Williams name was called from a list of inactive reserves to serve in the Korean War on January 9, 1952. Williams, who was livid at his recalling, had a physical scheduled for April 2.[114] Williams passed his physical, and was named a Captain in the Marine Corps after only playing in six games. Right before leaving for Korea, the Red Sox had a "Ted Williams Day" in Fenway Park. Friends of Williams gave him a Cadillac, and the Red Sox gave Williams a memory book that was signed by 400,000 fans. The Governor of Massachusetts and Mayor of Boston were there, along with a Korean veteran in a wheelchair. At the end of the ceremony, everyone in the park held hands and sang "Auld Lang Syne" to Williams, to which he later said that the moment "moved me quite a bit".[115] The Red Sox went on to win 5-3 thanks to a two-run home run by Williams in the seventh inning.[115] Williams, after returning from the Korean War in August 1953, practiced with the Red Sox for ten days before playing in his first game back, garnering a large ovation from the crowd and hitting a home run in the eighth inning.[116] In the season, Williams ended up hitting .407 with 13 home runs and 34 RBIs in 37 games and 110 at bats.[39] On September 6, Williams hit his 332nd career home run, passing Hank Greenberg for seventh all-time.[112][117]

On the first day of spring training in 1954, Williams broke his collarbone running after a line drive.[116] Williams was out for six weeks, and in April he wrote an article with Joe Reichler of the Saturday Evening Post saying that he intended to retire at the end of the season.[118] Williams returned to the Red Sox lineup on May 7, and he hit .345 with 386 at bats in 117 games, although Bobby Avila, who had hit .341, won the batting championship. This was because it was required then that a batter needed 400 at bats, despite Lou Boudreau's attempt to bat Williams second in the lineup to get more at-bats.[39][119] On August 25, Williams passed Johnny Mize for sixth place, and on September 3, Williams passed Joe DiMaggio for fifth all-time in career home runs with his 362nd career home run. He finished the season with 366 career home runs.[112][120] On September 26, Williams "retired" after the Red Sox's final game of the season.[121]

During the off-season of 1954, Williams was offered the chance to be manager of the Red Sox. Williams declined, and he suggested that Pinky Higgins, who had previously played on the 1946 Red Sox team as the third baseman, become the manager of the team. Higgins later was hired as the Red Sox manager in 1955.[122] Williams sat out the first month of the 1955 season due to a divorce settlement with his wife, Doris. When Williams returned, he signed a $98,000 contract on May 13. On his first game back, Williams hit a home run,[123] and he batted .356 in 320 at bats on the season, lacking enough at bats to win the batting title over Al Kaline, who batted .340 in 1955,[123] while hitting 28 home runs and driving in 83 runs,[39] while being named the "Comeback Player of the Year".[124]

1956 – 60[change | change source]

On July 17, 1956, Williams became the fifth player ever to hit 400 home runs, following Mel Ott in 1941, Jimmie Foxx in 1938, Lou Gehrig in 1936, and Babe Ruth in 1927.[125][126] On August 7, 1956, after Williams was booed for dropping a fly ball from Mickey Mantle, Williams spat at one of the fans that was taunting him on the top of the dugout.[127] Williams was fined $5,000 for the incident.[128] The next day against Baltimore, Williams was greeted by a large ovation, and received an even larger ovation when he hit a home run in the sixth inning to break a 2 - 2 tie. In The Boston Globe, the publishers ran a "What Globe Readers Say About Ted" section made out of letters about Williams, which were either the sportswriters or the "loud mouths" in the stands. Williams explained years later, "From '56 on, I realized that people were for me. The writers had written that the fans should show me they didn't want me, and I got the biggest ovation yet".[129] Williams lost the batting title to Mickey Mantle in 1956, batting .345 to Mantle's .353, with Mantle on his way to winning the Triple Crown.[130]

In 1957, Williams batted .388 to lead the Major Leagues, and remarkably at the age of 40 in 1958, he led the American League with a .328 batting average.

When Pumpsie Green became the first black player on the Boston Red Sox in 1959 — the last major league team to integrate its team — Williams openly welcomed Green.

Williams ended his career dramatically, hitting a home run in his very last at-bat on September 28, 1960. The classic John Updike essay "Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu" chronicles this event and is often mentioned among the greatest pieces of sports writing in American journalism.[131]

Williams is one of only 29 players in baseball history to date to have appeared in Major League games in four decades.

Playing style[change | change source]

Williams was an obsessive student of hitting. He famously used a lighter bat than most sluggers, because it generated a faster swing. David Halberstam's Summer of '49 recalls him warning teammates not to leave their bats on the ground as they would absorb moisture and become heavier. His biographer Leigh Montville relates the often told story that Hillerich & Bradsby presented Williams with four bats weighing 34 ounces and one weighing 33 1/2 ounces, and challenged him to identify the lighter bat, which he was consistently able to do. His devotion allowed him to hit for power and average while maintaining extraordinary plate discipline. In 1970 he wrote a book on the subject, The Science of Hitting (revised 1986), which is still read by many baseball players. Williams was known to discuss hitting with active players enthusiastically until very late in his life. A conversation with Tony Gwynn was filmed for television.

Williams nearly always took the first pitch, reasoning that the ability to gauge the pitcher's "stuff" was worth conceding a first strike. He was occasionally criticized for refusing to swing at a borderline pitch to put a ball in play when it might have helped advance a runner or score a run (a recurring theme among sportswriter critics was that "Ted plays for himself."). Yet, Williams argued persuasively about the great advantage that accrues to pitchers when hitters swing at a pitch even one baseball width outside the strike zone. In a graphic from 1968 that accompanied an article in Sports Illustrated magazine, Williams divided the strike zone into 77 baseballs, with each baseball containing his projected batting average for pitches thrown in that location.

Williams was frequently critical of pitchers and their refusal to bring the related kind of strategic thinking to their pitch selection that he brought to hitting. However, he did show great respect for Red Sox pitcher Bill "Spaceman" Lee, crediting him with that kind of mindset.

Williams lacked foot speed, as attested by his 19-year career total of only one inside-the-park home run, one occasion of hitting for the cycle, and just 24 stolen bases. (Interestingly, despite his slowness on the basepaths, he is one of only four players in history - along with the noted speedsters Tim Raines, Rickey Henderson, and Omar Vizquel - to have stolen a base in four different decades.) Williams always felt that had he had more speed, he could have raised his average considerably and helped him hit .400 in at least one more season. Williams was sometime considered to be an indifferent outfielder with a good throwing arm. He often spent time in left field practicing "shadow swings" for his next at-bat. Williams occasionally expressed regret that he had not worked harder on his defense. However, Williams did become an expert at playing the rebounds of batted balls off of the left-field wall and fences in Fenway Park. Later on, he helped pass this expertise to the left-fielder Carl Yastrzemski of the Red Sox.

Military service[change | change source]

| Theodore Samuel "Ted" Williams | |

|---|---|

Williams being sworn into the military on May 22, 1942. | |

| Born | August 30, 1918 |

| Died | July 5, 2002 |

| Place of burial | Scottsdale, Arizona |

| Allegiance | United States of America |

| Service/branch | United States Navy United States Marine Corps |

| Years of service | 1942-1946, 1952-53 |

| Rank | Captain |

| Battles/wars | World War II Korean War |

| Other work | Baseball player |

World War II[change | change source]

Williams served as a naval aviator (a U.S. Marine Corps pilot) during World War II and the Korean War. He had been classified 3-A by Selective Service prior to the war, a dependency deferment because he was his mother's sole means of financial support. When his classification was changed to (1-A) following the American entry into World War II, Williams appealed to his local draft board. The draft board ruled that his draft status should not have been changed. He made a public statement that once he had built up his mother's trust fund, he intended to enlist. Even so, criticism in the media, including withdrawal of an endorsement contract by Quaker Oats, resulted in his enlistment in the Marine Corps on May 22, 1942.

Williams could have received an easy assignment and played baseball for the Navy or the Marine Corps. Instead, he decided to defend his country and he joined the V-5 program to become a Naval aviator. Williams was first sent to the Navy's Preliminary Ground School at Amherst College for six months of academic instruction in various subjects including math and navigation, where he achieved a 3.85 grade point average.

Williams's Red Sox teammate, Johnny Pesky, who went into the same aviation training program, said this about Williams: "He mastered intricate problems in fifteen minutes which took the average cadet an hour, and half of the other cadets there were college grads."

Pesky again described Williams's acumen in the advance training for which Pesky personally did not qualify: "I heard Ted literally tore the sleeve target to shreds with his angle dives. He'd shoot from wingovers, zooms, and barrel rolls, and after a few passes the sleeve was ribbons. At any rate, I know he broke the all-time record for hits." Ted went to Jacksonville for a course in aerial gunnery, the combat pilot's payoff test, and broke all the records in reflexes, coordination, and visual-reaction time. "From what I heard. Ted could make a plane and its six 'pianos' (machine guns) play like a symphony orchestra," Pesky says. "From what they said, his reflexes, coordination, and visual reaction made him a built-in part of the machine."[132]

Williams completed pre-flight training in Athens, Georgia, his primary training at NAS Bunker Hill, Indiana, and his advanced flight training at NAS Pensacola. He received his pilot's wings and his commission in the U.S. Marine Corps on May 2, 1944.

Williams served as a flight instructor at the Naval Air Station Pensacola teaching young pilots to fly the complicated F4U Corsair fighter plane. Williams was in Pearl Harbor awaiting orders to join the Fleet in the Western Pacific when the War in the Pacific ended. He finished the war in Hawaii, and then he was released from active duty on January 12, 1946, but he did remain in the Marine Forces Reserves.[80]

Korean War[change | change source]

On May 1, 1952, at the age of 34, Williams was recalled to active duty for service in the Korean War. He had not flown any aircraft for about eight years but he turned down all offers to sit out the war in comfort as a member of a service baseball team. Nevertheless, Williams was somewhat resentful of being called up, which he admitted years later, particularly regarding the Navy's odd policy of calling up Inactive Reservists rather than members of the Active Reserve.

After eight weeks of refresher flight training and qualification in the F9F Panther jet fighter at the Marine Corps Air Station Cherry Point, North Carolina, Williams was assigned to VMF-311, Marine Aircraft Group 33 (MAG-33), based at the K-3 airfield in Pohang, South Korea.[80]

On February 16, 1953, Williams was part of a 35-plane air raid against a tank and infantry training school just south of Pyongyang, North Korea. During the mission a piece of flak knocked out his hydraulics and electrical systems, causing Williams to have to "limp" his plane back to K-13, a U.S. Air Force airfield close to the front lines. For his actions of this day he was awarded the Air Medal.

Williams stayed on K-13 for several days while his plane was being repaired. Because he was so popular, GIs and airmen from all around the base came to see him and his plane. After it was repaired, Williams flew his plane back to his Marine Corps airfield.

In Korea, Williams flew 39 combat missions before being being withdrawn from flight status in June 1953 after a hospitalization for pneumonia. This resulted in the discovery of an inner ear infection that disqualified him from flight status.[133] During the Korean War, Williams also served in the same Marine Corps unit with John Glenn, and in the last half of his missions, Williams was flying as Glenn's wingman.

While these absences in the Marine Corps, which took almost five years out of the heart of a great baseball career, significantly limited his career totals, he never publicly complained about the time devoted to service in the Marine Corps. His biographer Leigh Montville argued that Williams was not happy about being pressed into service in South Korea, but he did what he thought was his patriotic duty.

Williams had a strong respect for General Douglas MacArthur, referring to him as his "idol".[134] For Williams' fortieth birthday, MacArthur sent him an oil painting of himself with the inscription "To Ted Williams - not only America's greatest baseball player, but a great American who served his country. Your friend, Douglas MacArthur. General U.S. Army."[135]

Relationship with Boston media and fans[change | change source]

Ted Williams was on uncomfortable terms with the Boston newspapers for nearly twenty years, as he felt they liked to discuss his personal life as much as his baseball performance. He maintained a career-long feud with SPORT magazine due to a 1948 feature article in which the SPORT reporter included a quote from Williams' mother. Insecure about his upbringing, and stubborn because of immense confidence in his own talent, Williams made up his mind that the "knights of the Press Box" were against him. Some seemingly were. After having hit for the league's Triple Crown in 1947, Williams narrowly lost the MVP award in a vote where one midwestern newspaper writer left Williams entirely off his ten-player ballot.

He treated most of the press accordingly, as he described in his memoir, My Turn at Bat. Williams also had an uneasy relationship with the Boston fans, though he could be very cordial one-on-one. He felt at times a good deal of gratitude for their passion and their knowledge of the game. On the other hand, Williams was temperamental, high-strung, and at times tactless. In his biography, Ronald Reis relates how Williams committed two fielding miscues in a doubleheader in 1950 and was roundly booed by Boston fans. He bowed three times to various sections of Fenway Park and made an obscene gesture. When he came to bat he spit in the direction of fans near the dugout. The incident caused an avalanche of negative media reaction, and inspired sportswriter Austen Lake's famous comment that when Williams name was announced the sound was like "autumn wind moaning through an apple orchard."

Another incident occurred in 1958 in a game against the Washington Senators. Williams struck out, and as he stepped from the batters box swung his bat violently in anger. The bat slipped from his hands, was launched into the stands and struck a 60 year-old woman — one who turned out to be the housekeeper of the Red Sox general manager Joe Cronin. While the incident was an accident and Williams apologized to the woman personally, to all appearances it seemed at the time that Williams had hurled the bat in a fit of temper.

One of the paradoxes of Williams life is that he gave generously to those in need. He was especially linked with the Jimmy Fund of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, which provides support for children's cancer research and treatment. Williams used his celebrity to virtually launch the fund, which has raised more that $750 million between 1948 and 2010. Throughout his career, Williams made countless bedside visits to children being treated for cancer, which Williams insisted on going unreported. Often, parents of sick children would learn at check-out time that "Mr. Williams has taken care of your bill." [136] The Fund recently stated that, "Williams would travel everywhere and anywhere, no strings or paychecks attached, to support the cause . . . . His name is synonymous with our battle against all forms of cancer."[137]

Williams demanded loyalty from those around him. He could not forgive the fickle nature of the fans — booing a player for booting a ground ball, then turning around and roaring approval of the same player for hitting a home run. Despite the cheers and adulation of most of his fans, the occasional boos directed at him in Fenway Park led Williams to stop tipping his cap in acknowledgement after a home run.

Williams maintained this policy up to and including his swan song in 1960. After hitting a home run in his last career at-bat in Fenway Park, Williams characteristically refused either to tip his cap as he circled the bases or to respond to prolonged cheers of "We want Ted!" from the crowd by making an appearance from the dugout. The Boston manager Pinky Higgins sent Williams to his fielding position in left field to start the ninth inning, but then immediately recalled him for his back-up Carroll Hardy, thus allowing Williams to receive one last ovation as he jogged on and off the field. But he did so without reacting to the crowd. Williams's aloof attitude led the writer John Updike to wryly observe that "Gods do not answer letters."

Williams's final home run did not take place during the final game of the 1960 season, but rather in the Red Sox's last home game that year. The Red Sox played three more games, but they were on the road in New York City and Williams did not appear in any of them, as it became clear that Williams's final home at-bat would be the last one of his career.

In 1991 on Ted Williams Day at Fenway Park, Williams pulled a Red Sox cap from out of his jacket and tipped it to the crowd. This was the first time that he had done so since his earliest days as a player.

A Red Smith profile from 1956 describes one Boston writer trying to convince Ted Williams that first cheering and then booing a ballplayer was no different from a moviegoer applauding a "western" movie actor one day and saying the next "He stinks! Whatever gave me the idea he could act?" But Williams rejected this; when he liked a western actor like Hoot Gibson, he liked him in every picture, and would not think of booing him.

He once had a friendship with Ty Cobb, with whom he often had discussions about baseball. He often touted Rogers Hornsby as being the greatest right-handed hitter of all time. This assertion actually led to a split in the relationship between Ty Cobb and Ted Williams. Once during one of their yearly debate sessions on the greatest hitters of all-time Williams asserted that Hornsby was one of the greatest of all-time. Cobb apparently had strong feelings about Rogers and he threw a fit, expelling Williams from his hotel room. Their friendship effectively terminated after this altercation.[138]

Hall of Fame induction speech[change | change source]

In his induction speech in 1966, Williams included a statement calling for the recognition of the great Negro Leagues players: "I've been a very lucky guy to have worn a baseball uniform, and I hope some day the names of Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson in some way can be added as a symbol of the great Negro players who are not here only because they weren't given a chance." (Montville, p. 262).

Williams was referring to two of the most famous names in the Negro Leagues, who were not given the opportunity to play in the Major Leagues before Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in 1947. Gibson died early in 1947 and thus never played in the majors; and Paige's brief major league stint came long past his prime as a player. This powerful and unprecedented statement from the Hall of Fame podium was "a first crack in the door that ultimately would open and include Paige and Gibson and other Negro League stars in the shrine." (Montville, p. 262) Paige was the first inducted, in 1971. Gibson and others followed, starting in 1972 and continuing off and on into the 21st Century.

In 1954, Williams was also inducted by the San Diego Hall of Champions into the Breitbard Hall of Fame honoring San Diego's finest athletes both on and off the playing surface.[4]

Career ranking[change | change source]

At the time of his retirement, Williams ranked third all-time in home runs (behind Babe Ruth and Jimmie Foxx), seventh in RBIs (after Ruth, Cap Anson, Lou Gehrig, Ty Cobb, Foxx, and Mel Ott; Stan Musial passed Williams in 1962), and seventh in batting average (behind Cobb, Rogers Hornsby, Shoeless Joe Jackson, Lefty O'Doul, Ed Delahanty and Tris Speaker). His career batting average is the highest of any player who played his entire career in the live-ball era following 1920.

Williams was also second to Ruth in career slugging percentage, where he remains today, and first in on-base percentage. He was also second to Ruth in career walks, but has since dropped to fourth place behind Barry Bonds and Rickey Henderson. Williams remains the career leader in walks per plate appearance.

Most modern statistical analyses place Williams, along with Ruth and Bonds, among the three most potent hitters to have played the game. Williams's baseball season of 1941 is often considered favorably with the greatest seasons of Ruth and Bonds in terms of various offensive statistical measures such as slugging, on-base and "offensive winning percentage." As a further indication, of the ten best seasons for OPS, short for On-Base Plus Slugging Percentage, a popular modern measure of offensive productivity, four each were achieved by Ruth and Bonds, and two by Williams.

Although Williams' career did not overlap with that of Ruth or Bonds, a direct comparison with another great hitter, Hank Aaron, is possible. From 1955 to 1960, Williams maintained an average OPS of 1.092, as compared with .950 for Aaron. Williams' age (37-42) was well past the prime of most hitters, but he still managed to hit .388 at the age of 39. Although Aaron (age 21 - 26) recorded only one of his five best seasons, their averages are not too far from the career averages of the two baseball players.

In 1999, Williams was ranked as number eight on The Sporting News' list of the 100 Greatest Baseball Players, where he was the highest-ranking left fielder.[139]

Family life[change | change source]

On May 4, 1944, Williams married Doris Soule, daughter of his hunting guide. Their daughter, Barbara Joyce ("Bobbi Jo"), was born on January 28, 1948, while Williams was fishing in Florida.[140] They divorced in 1954. Williams married the socialite model Lee Howard on September 10, 1961, but they divorced in 1967.

Williams married Dolores Wettach, a former Miss Vermont and Vogue model, in 1968. Their son John-Henry was followed by daughter Claudia (born October 8, 1971). They were divorced in 1972.[141]

Williams lived with Louise Kaufman for twenty years until her death in 1993. In his book, Cramer called her the love of Williams's life.[142] After his death, her sons filed suit to recover her furniture from Williams's condominium as well as a half-interest in the condominium they claimed he gave her.[143]

Both John-Henry and Williams's brother Danny died of leukemia.

Retirement[change | change source]

After retirement from play, Williams helped new left fielder Carl Yastrzemski in hitting. He then served as manager of the Washington Senators, from 1969–1971, then continued with the team when they became the Texas Rangers after the 1971 season. Williams's best season as a manager was 1969 when he led the expansion Senators to an 86–76 record in the team's only winning season in Washington. He was chosen "Manager of the Year" after that season. Like many great players, Williams became impatient with ordinary athletes' abilities and attitudes, particularly those of pitchers, whom he admitted he never respected. He occasionally appeared at Red Sox spring training as a guest hitting instructor. Williams would also go into a partnership with friend Al Cassidy to form the Ted Williams Baseball Camp in Lakeville, Massachusetts. It was not uncommon to find Williams fishing in the pond at the camp. The area now is owned by the town and a few of the buildings still stand. In the main lodge one can still see memorabilia from Williams' playing days.

On the subject of pitchers, in Ted's autobiography written with John Underwood, Ted opines regarding Bob Lemon (a sinker-ball specialist) pitching for Cleveland Indians around 1951: "I have to rate Lemon as one of the very best pitchers I ever faced. His ball was always moving, hard, sinking, fast-breaking. You could never really uhmmmph with Lemon."

Williams was much more successful in fishing. An avid and expert fly fisherman and deep-sea fisherman, he spent many summers after baseball fishing the Miramichi River, in Miramichi, New Brunswick, Canada. Williams was named to the International Game Fish Association Hall of Fame in 2000. Thus, he is the only athlete to be inducted into the Halls of Fame of two different sports. Shortly after Williams's death, conservative pundit Steve Sailer wrote:

The baseball slugger was possibly the most technically proficient American of the 20th Century, as his mastery of three highly different callings demonstrates... Can you think of anybody else who was #1 in America in his main career [hitting a baseball], probably Top 10 in his retirement hobby [fishing], and roughly Top 1000 in his weekend job [fighter pilot]? [John] Glenn springs to mind as military pilot, astronaut, and Senator, but each new career flowed from the previous one. The same is true for Jimmy Doolittle. Williams' three careers, in contrast, were uniquely disparate.[144]

Williams reached an extensive deal with Sears, lending his name and talent toward marketing, developing, and endorsing a line of in-house sports equipment - specifically fishing, hunting, and baseball equipment. Williams continued his involvement in the Jimmy Fund, later losing a brother to leukemia, and spending much of his spare time, effort, and money in support of the cancer organization.

In his later years, Williams became a fixture at autograph shows and card shows after his son (by his third wife), John Henry Williams, took control of his career, becoming his de facto manager. The younger Williams provided structure to his father's business affairs, exposed forgeries that were flooding the memorabilia market, and rationed his father's public appearances and memorabilia signings to maximize their earnings.

On November 18, 1991, Ted Williams was presented with the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President George H. W. Bush.

One of Ted Williams's final, and most memorable, public appearances was at the 1999 All-Star Game in Boston. Able to walk only a short distance, Williams was brought to the pitcher's mound in a golf cart. He proudly waved his cap to the crowd — a gesture he had never done as a player. Fans responded with a standing ovation that lasted several minutes. At the pitcher's mound he was surrounded by players from both teams, including fellow Red Sox player Nomar Garciaparra. Later in the year, he was among the members of the Major League Baseball All-Century Team introduced to the crowd at Turner Field in Atlanta prior to Game two of the World Series.

The Ted Williams Tunnel in Boston (December 1995), and Ted Williams Parkway in San Diego County (1992) were named in his honor while he was still alive.

Death[change | change source]

In his last years, Williams suffered from cardiomyopathy. He had a pacemaker implanted in November 2000 and he underwent open-heart surgery in January 2001. After suffering a series of strokes and congestive heart failure, he died of cardiac arrest at the age of 83 in Citrus Hills, Florida, on July 5, 2002.

Though his will stated his desire to be cremated and his ashes scattered in the Florida Keys, John-Henry and Claudia chose to have his remains frozen cryonically.

Ted's eldest daughter, Bobby-Jo Ferrell, brought suit to have her father's wishes recognized. John-Henry's lawyer then produced an informal "family pact" signed by Ted, John-Henry, and Ted's daughter Claudia, in which they agreed "to be put into biostasis after we die" to "be able to be together in the future, even if it is only a chance."[145] Bobby-Jo and her attorney, Richard S. "Spike" Fitzpatrick (former attorney of Ted Williams), contended that the family pact, which was scribbled on an ink-stained napkin, was forged by John-Henry and/or Claudia.[146] Fitzpatrick and Ferrell believed that the signature was not obtained legally.[147] Laboratory analysis proved that the signature was genuine.[147] John-Henry said that his father was a believer in science and was willing to try cryonics if it held the possibility of reuniting the family.[148]

Though the family pact upset some friends, family and fans, a public plea for financial support of the lawsuit by Ferrell produced little result.[148] Citing financial difficulties, Ferrell dropped her lawsuit in exchange that a $645,000 trust fund left by Williams would immediately pay the sum out equally to the three children.[148] Inquiries to cryonics organizations increased after the publicity from the case.[146]

In Ted Williams: The Biography of an American Hero, author Leigh Montville claims that the family cryonics pact was a practice Ted Williams autograph on a plain piece of paper, around which the agreement had later been hand written. The pact document was signed "Ted Williams", the same as his autographs, whereas he would always sign his legal documents "Theodore Williams", according to Montville. However, Claudia testified to the authenticity of the document in a sworn affidavit.[149] Ted's two 24-hour private caregivers who were with him the entire period the note was said to have been created also stated in sworn affidavits that John-Henry and Claudia were never present at any time for that note to be produced.

Following John-Henry's unexpected illness and death from acute myelogenous leukemia on March 6, 2004, John-Henry's body was also transported to Alcor, in fulfillment of the family agreement.[150]

According to the book "Frozen", co-authored by Larry Johnson (who is a former executive from Alcor), Williams' head was damaged by a worker when Alcor employees were handling the head. Although Johnson didn't work at Alcor when Ted was initially preserved, he claimed witness of the handling of the frozen head during a transfer to its final container (though numerous other Alcor employees refute this claim).[151]

The Tampa Bay Rays home field, Tropicana Field, has installed the Ted Williams Museum (formerly in Hernando, Florida) behind the left field fence. From the Tampa Bay Rays website: "The Ted Williams Museum and Hitters Hall of Fame brings a special element to the Tropicana Field. Fans can view an array of different artifacts and pictures of the 'Greatest hitter that ever lived.' These memorable displays range from Ted Williams' days in the military through his professional playing career. This museum is dedicated to some of the greatest players to ever 'lace 'em up,' including Willie Mays, Joe DiMaggio, Mickey Mantle, Roger Maris."

Career batting statistics[change | change source]

| Career | G | AB | R | H | 2B | 3B | HR | GS | RBI | SB | CS | BB | IBB | SO | SH | SF | HBP | GIDP | AVG | OBP | SLG | OPS | OPS+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19 Years | 2,292 | 7,706 | 1,798 | 2,654 | 525 | 71 | 521 | 17 | 1,839 | 24 | 17 | 2,021 | 86 | 709 | 5 | 20 | 39 | 197 | .344 | .482 | .634 | 1.116 | 190 |

See also[change | change source]

- Red Sox Hall of Fame

- List of Major League Baseball Home Run Records

- 500 home run club

- DHL Hometown Heroes

- List of MLB individual streaks

- List of top 300 Major League Baseball home run hitters

- List of major league players with 2,000 hits

- List of Major League Baseball players with 400 doubles

- List of Major League Baseball players with 1000 runs

- List of Major League Baseball players with 1000 RBIs

- Hitting for the cycle

- Triple Crown

- List of Major League Baseball RBI champions

- List of Major League Baseball batting champions

- List of Major League Baseball home run champions

- List of Major League Baseball runs scored champions

- List of Major League Baseball doubles champions

- Major League Baseball titles leaders

Notes[change | change source]

- ↑ "Ted Williams at the Baseball Hall of Fame". National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Retrieved February 6, 2011.

- ↑ Denby, David (October 3, 2011). ""Playing the Numbers"". The New Yorker.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ Kurkjian, Ted (July 5, 2002). "Williams is the greatest hitter of any time". ESPN Classic. Retrieved September 19, 2011.

- ↑ "IGFA Hall of Fame Inductees". International Game Fish Association. Retrieved August 29, 2011.

- ↑ Seidel, p. 1

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Montville, p. 19

- ↑ Williams & Underwood, p. 31

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Seidel, p. 2

- ↑ Williams & Underwood, p. 30

- ↑ Seidel, p. 4

- ↑ Montville, p. 21

- ↑ Montville, Leigh (April 25, 2004). "Their devotion was religious". The Boston Globe. Retrieved March 13, 2011.

- ↑ Addams Reitwiesner, William. "Ancestry of Ted Williams". Wargs.com. Retrieved March 12, 2011.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Williams & Underwood, p. 28

- ↑ Nowlin, p. 324

- ↑ Montville, p. 20

- ↑ Nowlin & Price, p. 31

- ↑ Montville, p. 22

- ↑ McCormack, p. 14

- ↑ Montville, p. 26

- ↑ Nowlin, p. 118

- ↑ Meserole, Mike (July 8, 2002). "'There goes the greatest hitter who ever lived'". ESPN Classic. Retrieved March 13, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ↑ Williams & Underwood, p. 7

- ↑ Montville, p. 32

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 25.4 Montville, p. 33-34

- ↑ Nowlin, p. 98

- ↑ Nowlin, p. 100

- ↑ Williams & Underwood, p. 43

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Williams & Underwood, p. 45

- ↑ Reis, p. 14

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Montville, p. 46

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Montville, p. 45

- ↑ Montville, p. 47

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 34.3 Montville, p. 48-49

- ↑ Montville, p. 53

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Montville, p. 56–57

- ↑ Williams & Underwood, p. 57

- ↑ Montville, p. 57

- ↑ 39.00 39.01 39.02 39.03 39.04 39.05 39.06 39.07 39.08 39.09 39.10 39.11 39.12 "Ted Williams Statistics and History". Baseball-reference.com. Retrieved March 22, 2011.

- ↑ Williams & Underwood, p. 61

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Williams & Underwood, p. 62

- ↑ Montville, p. 61

- ↑ Williams & Underwood, p. 63

- ↑ Montville, p. 62

- ↑ Williams & Underwood, p. 65

- ↑ Williams & Underwood, p. 73

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Montville, p. 63

- ↑ Montville, p. 64

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 "All-Star Game Moments". CBS Sports. Retrieved March 26, 2011.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Shaughnessy, Dan (July 5, 2002). "Easily, he was the brightest light". The Boston Globe. Retrieved March 22, 2011.

- ↑ Montville, p. 66-67

- ↑ "The Chronology - 1940". BaseballLibrary.com. Retrieved March 22, 2011.

- ↑ Williams & Underwood, p. 82

- ↑ Williams & Underwood, p. 84

- ↑ Montville, p. 80

- ↑ Reis, p. 26

- ↑ Montville, p. 82-83

- ↑ Montville, p. 84

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 Montville, p. 85

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 60.2 60.3 Williams & Underwood, p. 88

- ↑ "1941 All-Star Game Box Score". Baseball-almanac.com. Retrieved March 23, 2011.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 62.2 62.3 Williams & Underwood, p. 87

- ↑ Williams & Underwood, p. 86

- ↑ Montville, p. 90

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 65.2 65.3 Williams & Underwood, p. 89-96

- ↑ Montville, p. 94

- ↑ <<http://www.baseball-reference.com/teams/BOS/leaders_bat_50.shtml>>

- ↑ Linn, p. 168

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 Williams & Underwood, p. 97

- ↑ Reis, p. 36

- ↑ 71.0 71.1 71.2 Williams & Underwood, p. 98

- ↑ Montille, p. 101

- ↑ http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/gl.cgi?id=willite01&t=b&year=1942

- ↑ http://www.sporcle.com/games/Eric/RedSox_HRs

- ↑ Montville, p. 108

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 Montville, p. 110

- ↑ Montville, p. 111

- ↑ Montville, p. 117-118

- ↑ Montville, p. 119

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 80.2 Mersky, p. 189

- ↑ Montville, p. 122

- ↑ Williams & Underwood, p. 107

- ↑ Williams & Underwood, p. 113

- ↑ "July 9, 1946 All-Star Game Play-by-Play and Box Score". Baseball-reference.com. Retrieved March 25, 2011.

- ↑ Montville, p. 127

- ↑ Montville, p. 125

- ↑ 87.0 87.1 87.2 Montville, p. 126

- ↑ "1946 World Series by Baseball Almanac". Baseball-almanac.com. Retrieved March 25, 2011.

- ↑ Montville, p. 131

- ↑ Williams & Underwood, p. 105

- ↑ Williams & Underwood, p. 122

- ↑ Merron, Jeff. "Baseball's biggest rumors". ESPN. Retrieved March 25, 2011.

- ↑ Seidel, p. 177

- ↑ Williams & Underwood, p. 124

- ↑ 95.0 95.1 Montville, p. 134

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ 97.0 97.1 97.2 Montville, p. 133

- ↑ "1948 Awards Voting". Baseball-reference.com. Retrieved March 25, 2011.

- ↑ 99.0 99.1 http://www.baseball-reference.com/teams/BOS/leaders_bat_50.shtml

- ↑ http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/gl.cgi?id=willite01&t=b&year=1948

- ↑ "Game of Monday, 10/4/1948 -- Cleveland at Boston (D)". Retrosheet.org. Retrieved March 25, 2011.

- ↑ Neyer, p. 65

- ↑ Montville, p. 135

- ↑ http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/gl.cgi?id=willite01&t=b&year=1949

- ↑ "1949 Boston Red Sox Schedule by Baseball Almanac". Baseball-almanac.com. Retrieved March 25, 2011.

- ↑ 106.0 106.1 Mnookin, p. 33

- ↑ Williams & Underwood, p. 167

- ↑ Williams & Underwood, p. 168

- ↑ Williams & Underwood, p. 169

- ↑ Linn, p. 241

- ↑ 111.0 111.1 111.2 Williams & Underwood, p. 172

- ↑ 112.0 112.1 112.2 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_lifetime_home_run_leaders_through_history

- ↑ http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/gl.cgi?id=willite01&t=b&year=1951

- ↑ Montville, p. 152

- ↑ 115.0 115.1 Williams & Underwood, p. 174

- ↑ 116.0 116.1 Williams & Underwood, p. 186

- ↑ http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/gl.cgi?id=willite01&t=b&year=1953

- ↑ Williams & Underwood, p. 187

- ↑ Williams & Underwood, p. 188

- ↑ http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/gl.cgi?id=willite01&t=b&year=1954

- ↑ Montville, p. 189

- ↑ Williams & Underwood, p. 191

- ↑ 123.0 123.1 Williams & Underwood, p. 192

- ↑ Montville, p. 91

- ↑ http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/gl.cgi?id=willite01&t=b&year=1956

- ↑ http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/w/willite01.shtml

- ↑ Montville, p. 197-198

- ↑ Montville, p. 198

- ↑ Montville, p. 199

- ↑ Williams & Underwood, p. 197

- ↑ [2]

- ↑ Linn, p. 246-247

- ↑ Mersky, p. 190

- ↑ Montville, p. 12

- ↑ Montville, p. 13-14

- ↑ http://www.jimmyfund.org/abo/red/tedwilliams/facts.asp

- ↑ "http://www.jimmyfund.org/abo/red/tedwilliams/facts.asp

- ↑ Stump, Al. "Cobb: A Biography." Algonquin Books, 1994

- ↑ "Baseball's 100 Greatest Players". The Sporting News. April 1999. p. 20.

- ↑ "Williams Family Values" Boston Magazine Accessed January 23, 2009

- ↑ Hitter, Ed Linn, p. 355/7

- ↑ Hitter, p 86

- ↑ "Williams children seek insurance money" St. Petersburg Times December 15, 2002 Accessed January 23, 2009

- ↑ Sailer, Steve (July 2002). "Ted Williams, RIP". isteve.com. Retrieved 2008-04-18.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) (scroll down to near bottom of page) - ↑ Ted Williams Frozen In Two Pieces, Meant To Be Frozen In Time; Head Decapitated, Cracked, DNA Missing - CBS News

- ↑ 146.0 146.1 Citrus: Williams' shift from will must be proved

- ↑ 147.0 147.1 "Newspaper Archives". <!.

{{cite news}}: Text "tampabay.com - St. Petersburg Times" ignored (help) - ↑ 148.0 148.1 148.2 Sandomir, Richard (2002-12-21). "Williams Children Agree to Keep Their Father Frozen". New York Times. Retrieved 2008-11-21.

- ↑ [3]

- ↑ ESPN - Leukemia claims son of Hall of Famer - MLB

- ↑ Vinton, Nathaniel (October 2, 2009). "Ted Williams' frozen head for batting practice at cryogenics lab: book". Daily News. New York.

References[change | change source]

- Linn, Ed. Hitter: The Life And Turmoils of Ted Williams. Harcourt Brace and Company, 1993. ISBN 0-15-600091-1.

- Mersky, Peter B. (1983). U.S. Marine Corps Aviation: 1912 to the Present. Annapolis, Maryland: Nautical and Aviation Publishing Company of America. ISBN 0-933852-39-8..

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - Montville, Leigh. Ted Williams: The Biography of an American Hero. New York: Doubleday, 2004. ISBN 0-385-50748-8.

- Neyer, Rob. Rob Neyer's Big Book of Baseball Blunders. Fireside, 2006. ISBN 0-7432-8491-7.

- Nowlin, Bill. The Kid: Ted Williams in San Diego. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Rounder Books, 2005. ISBN 1-57940-094-9.

- Nowlin, Bill and Jim Prime. Ted Williams: The Pursuit of Perfection. Sports Publishing, LLC, 2002. ISBN 1-58261-495-4.

- McCormack, Shaun. Ted Williams. The Rosen Publishing Group, 2004. ISBN 0-8293-3789-6.

- Mnookin, Seth. Feeding the Monster: How Money, Smarts, and Nerve Took a Team to the Top. Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, 2006. ISBN 0-7432-8681-2.

- Reis, Ronald. Ted Williams. Infobase Publishing, 2008. ISBN 978-0-7910-9545-4.

- Seidel, Michael (2000). Ted Williams: A Baseball Life. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-9280-5.

- Williams, Ted, and John Underwood. My Turn at Bat: The Story of My Life. Fireside Classics, 1970, 1989. ISBN 0-671-63423-2.

- SPORT magazine, April 1948.

Further reading[change | change source]

- Baldasarro, Lawrence (ed.). The Ted Williams Reader. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1991. ISBN 0-671-73536-5.

- Halberstam, David. The Teammates. New York: Hyperion, 2003. ISBN 1-4013-0057-X.

- Updike, John. Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu: John Updike on Ted Williams. New York: Library of America, 2010. ISBN 978-1-59853-071-1

- Williams, Ted, and John Underwood. Ted Williams' Fishing the Big Three: Tarpon, Bonefish, Atlantic Salmon. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1982. ISBN 0-671-24400-0.

- Williams, Ted, and David Pietrusza. Ted Williams: My Life in Pictures (also published as Teddy Ballgame). Kingston, N.Y.: Total/Sports Illustrated, 2002. ISBN 1-930844-07-7.

- Williams, Ted, and Jim Prime. Ted Williams' Hit List: The Best of the Best Ranks the Best of the Rest. Indianapolis: Masters Press, 1996. ISBN 1-57028-078-9.

- Cramer, Richard Ben. What Do You Think Of Ted Williams Now? - A Remembrance. Simon & Schuster, 2002. ISBN 0-7432-4648-9.

- Cramer, Richard Ben. What do you think of Ted Williams now?. Esquire, June 1986.

External links[change | change source]

- Ted Williams at the Baseball Hall of Fame

- Career statistics and player information from Baseball-Reference, or Fangraphs, or The Baseball Cube

- Baseball Library

- Ted Williams: A life remembered - article at Boston Globe

- Ted Williams Tribute - article at Sports Illustrated

- Videos of Ted Williams Cryonics Debate

- Ted Williams Museum

- Photo of Ted Williams with Joe and Dom DiMaggio

- Ted Williams: Hitter - slideshow by Life magazine

- TrueCRaysball/Ted Williams at Find a Grave Retrieved on 2008-07-11

- TrueCRaysball/Ted Williams on IMDb

| Accomplishments | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||