Hispaniola

| Hispaniola | |

|---|---|

Topographic map of Hispaniola | |

| Geography | |

| Location | Caribbean Sea |

| Archipelago | Antilles |

| Area | 76,480 km2 (29,529 sq mi) |

| Highest point | Pico Duarte (3,087 m) |

| Countries | |

| President | Jovenel Moise |

| Capital city | Port-au-Prince (703,023) |

| President | Luis Abinader |

| Capital city | Santo Domingo (790,191) |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 15,222,428 |

| Density | 263 |

Hispaniola is an island in the Caribbean Sea. It is the second largest island (after Cuba) of the West Indies, east of Cuba and west of Puerto Rico. It is the most populous island of the West Indies.

The Republic of Haiti occupies the western three-eighths,[1][2] the Dominican Republic the rest. Hispaniola is one of two Caribbean islands in which there are two countries; the other is Saint Martin.

History[change | change source]

Pre-Columbian history[change | change source]

When Columbus arrived to America, some groups of native people, coming from northern South America, had lived in the Caribbean Islands since a very long time. That movement from South America to the Caribbean islands was not continuous but it happened in several waves during almost twelve centuries.

Archeological studies suggests that those people from South America came to the Caribbean islands during four periods.

The first period began around 5000 B.C. For most Caribbean islands, this period ended around 2000 years ago except in Cuba and Hispaniola where there were some small populations in western Cuba and southwestern Hispaniola when the Europeans arrived to these islands.[3] They were called Ciboney or Siboney by the Taínos, meaning "man that lives among rocks" (Ciba means stone and eyeri man).[4]

The second group was the Igneri, the first Arawak Indians to come to the Caribbean Islands. They displaced the Ciboney people and, later, they were displaced by another group of Arawak Indians, the Taínos. Taínos occupied all the Greater Antilles (Cuba, Jamaica, Hispaniola and Puerto Rico) and they developed a culture different from the culture of the Arawaks of South America. They were the first people that the Spanish met in the Americas.

The fourth and last group was the Carib. The Carib were also Arawaks but with a different language. Even if they used to go to Puerto Rico and the Hispaniola to fight against the Taínos, they lived only in the Lesser Antilles when Columbus got to America.

At the moment when the Spanish came to the Hispaniola, most of the island was occupied by Taínos; only in the western tip of the Southern Peninsula (in modern Haiti), there were some small groups of Ciboney In the northeastern part of the island (Samaná Peninsula and north of the Northern mountain range), there was a group called Ciguayos, and sometimes Macorix, with the same culture of the Taínos but a different language. It seems that they were Carib that took the Taíno culture.[5] They were the first Indians that fought against the Europeans.[6]

Discovery, conquest and colony[change | change source]

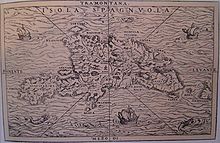

Christopher Columbus arrived to the island on December 5, 1492, naming it as La Española, meaning The Spanish Island. When Peter Martyr d'Anghiera wrote in latin about this island, he wrote Hispaniola, meaning Small Spain; that was not correct. Because the book of Anghiera was translated into English very soon, the name Hispaniola is the most used in English-speaking countries and in scientific works.

For centuries, other names were used for the island. The most common were Santo Domingo Island (the Dominican constitution still uses that name) and Haiti.

Hispaniola was the only island that Columbus visited in all his four travels to the Americas. He saw the island for the first time on December 5, 1492 but he stayed on his ship during the night; the next day, he went to land. The Spaniards spent the rest of December traveling along the north coast of Haiti; on December 12, Columbus took possession of the island in the name of the King and Queen of Spain and named the island as "La Española".[7]

On Christmas Eve, December 24, the main ship ("Santa María") was badly damaged. The next day, Christmas Day, Columbus gave orders to use the wood of the ship to build a small fort on what is now Môle Saint-Nicolas, Haiti. That fort was named La Navidad ("Navidad" means Christmas) and was the first European building on American soil. Columbus left 39 men there because there was not space in the other two ships for all the people.

From "La Navidad", they traveled east along the north coast of the island and in Samaná they had a small fight with some natives ("Ciguayos", not Taíno Indians) and named the bay as "Golfo de las Flechas" (Gulf of the Arrows), but now is called "Samaná Bay". From there, they went back to Spain.

In 1493, Columbus found, when he returned in his second trip, that "La Navidad" was destroyed by the Indians and all Spaniards killed. Then he went to the east, founding the first European city in the American continent, near the present city of Puerto Plata; he named the city "La Isabela" in honor of Queen Isabella of Castile.[8] The first Catholic mass in America was celebrated at La Isabela on January 6, 1494. From La Isabela, Columbus sent groups of persons to explore and take control of the island.

Because La Isabela was an unhealthy site, Bartholomew Columbus, brother of Christopher, established a new city, La Nueva Isabela (The New Isabela) on the south coast of the island, on the left side of the Ozama river. Because a hurricane destroyed the city, it was built again but on the right side of the river and with the new name of Santo Domingo. It is the oldest permanent European city in the Americas.

The Taíno population of the island decreased very fast because a combination of new diseases, like smallpox, and abuses by the Spaniards. Even if some black slaves were brought from Spain since 1501, the colony began to import African slaves when the colony began to grow sugar cane, around 1516, to produce sugar.[9]

Spain kept conquering new regions of the Americas and, for the Spanish people, those new regions were more interesting because there was more gold; the population of the island grew very slowly. By the early 17th century, the island and its smaller neighbors (above all, the Tortuga island) became places often visited by Caribbean pirates. In 1606, the king of Spain gave the order that all inhabitants of Hispaniola had to move close to the city of Santo Domingo, to avoid interaction with pirates and Protestant people. This resulted in French, British and Dutch pirates establishing bases on the abandoned north and west coasts of the island.

In 1665, the presence of French people on the island had the official approval of the French king Louis XIV and he named Bertrand d'Ogeron as the governor of the western part of Hispaniola (in French, Saint-Domingue). By the Treaty of Ryswick, Spain gave the western third of the island to France and kept the eastern part. The development of the French "Saint-Domingue" was very fast, both in wealth and population, and it became the richest colony in the Caribbean. The eastern, Spanish colony of "Santo Domingo" remained poor and with a very low population.

Geography[change | change source]

The island of Hispaniola has an area of 76,480 km2 (29,530 sq mi). There are two countries: the Republic of Haiti is in the western part of the island and the Dominican Republic in the eastern part. These two countries are separated by an artificial border, except in the northern and southern extremes where they are separated by the rivers Dajabón and Pedernales, respectively.

| Country | Population (July 2007 est.) |

Area (km²) |

Density (per km²) |

| Haiti | 9,893,934[10] | 27,750 | 357 |

| Dominican Republic | 10,219,630[11] | 48,730 | 210 |

| Total | 20,113,564 | 76,480 | 263 |

The island is separated from Cuba by the Windward Passage (81 km from Punta Maisí in Cuba to Cape Saint-Nicolas in Haiti), from Jamaica by the Jamaica Channel (186 km or 116 mi from Point Morante in Jamaica to Cape Irois in Haiti) and from Puerto Rico by the Mona Channel, as 112 km (70 mi) from Punta Higüero in Puerto Rico to Punta de Agua in the Dominican Republic.[12]

The maximun length, east to west, is 650 km (400 mi) from Cape Engaño to Cape Irois. The maximum width, north to south, is 265 km (165 mi) from Cape Isabela to Cape Beata.[12] The highest point of the island, and of the Caribbean is Duarte Peak (Pico Duarte) in the Dominican Republic with 3,087 m (10,128 ft); the lowest point is in the Enriquillo Lake, which is about 46 meters (151 ft) under sea level.[11]

Islands[change | change source]

There are many smaller islands around the Hispaniola. The largest are:

- Gonâve (French, Île de la Gonâve), in the Gulf of Gonâve. It is part of Haiti and has an area of 743 km².[13] Its Taíno name was Guanabo.[14]

- Tortuga (French, Île de la Tortue), close to the northern coast of Haiti, in the Atlantic Ocean. It is part of Haiti and has an area of 180 km2 (69 sq mi).[13] Its Taíno name was Baynei.[14] It is very famous because many pirates lived here.

- Saona, close to the southeastern coast of the Hispaniola, in the Caribbean Sea. It is part of the Dominican Republic and has an area of 117 km2 (45 sq mi).[12] Its Taíno name was Iai [14] or Adamanay. Columbus named this island as Savona after the Italian city of the same name but the use during years has eliminated the letter v.

- Île à Vache, also called Île-à-Vaches, close to the soutwestern coast of Hispaniola. It is part of Haiti and has an area of 52 km2 (20 sq mi).[13] Its Taíno name was Iabaque.[14]

- Beata, in the southern coast of the Hispaniola, in the Caribbean Sea. It is part of the Dominican Republic and has an area of 27 km2 (10 sq mi).[12] Nobody knows its Taíno name. Columbus named this island as Madama Beata.

- Cayemites, two islands, Petite Cayemite and Grand Cayemite, in the Gulf of Gonâve. They are part of Haiti with a total area of 45 km².[13] The Taíno name was Cahaimi.[14]

- Catalina, very close to the southeastern coast of the Hispaniola, in the Caribbean Sea. It is part of the Dominican Republic and has an area of 9.6 km².[13] Its Taíno name was Iabanea[14] but some writers, including poets, say that it was called Toeya or Toella. It was discovered by Columbus who named it as Santa Catalina.

- Navassa (French, La Navasse), in the Jamaica Channel with 5.2 km².[13] It is administered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The island is also claimed by Haiti.[15]

Mountains and valleys[change | change source]

The Hispaniola is an island with many mountains, and the highest peaks of the West Indies are here. The chains of mountains show a direction northwest-southeast, except in the Southern peninsula (in Haiti) where they have a direction west-east. The mountains are separated by valleys with the same general direction.

From north to south, the mountain ranges and valleys are:[16]

- Cordillera Septentrional (in English, "Northern Range"). It is a Dominican chain, with extensions to the northwest, the Tortuga Island, and to the southeast, the Samaná Peninsula (with its Sierra de Samaná). Its highest mountain is Diego de Ocampo, close to Santiago, with 1,249 m.

- The Plaine du Nord (Haiti) and Cibao Valley (Dominican Republic) is the largest, and perhaps the most important, valley of the island. This long valley stretches from North Haiti to Samaná Bay.

- The Massif du Nord (Haiti, with the Gros Morne, 1.198 m) and Cordillera Central (Dominican Republic, also called Sierra de Cibao) with the highest mountains of the West Indies: Duarte Peak, 3,087 m, and others above 3,000 m. Near the center of the island, this range divides itself in two branches: Cordillera Oriental or Sierra del Seibo, separated from the main chain by a depression and with a west-east direction, and a second branch with a north-south direction called Sierra de Ocoa.

- The Plateau Central (Haiti), San Juan Valley and Plain of Azua (Dominican Republic), are big valleys with elevation from 0 to 600 m.

- The Bombardopolis Plateau (640 m), Montagnes de Terre Neuve (1,100 m, Morne Goreille), Montagnes Noires (1,700 m, Pic Bonhomme). All this chains are in Haiti and form one group of mountains.

- Artibonite Plain and Valley, in Haiti, between those mountains mentioned above and below.

- Chaîne des Matheux (Morne Delpech, 1,600 m) and the Montagnes du Trou d'Eau (Morne Ma Pipe, 1,510 m) form one group that get together with the previous group of mountains to form, in the Dominican Republic, the Sierra de Neiba, with Mount Neiba the highest mountain with 2,279 m. An extension to the southeast of Sierra de Neiba is the Sierra Martín García (Loma Busú, 1,350 m).

- The Cul-de-Sac (Haiti) or Hoya de Enriquillo (Dominican Republic), is a remarkable valley, with a west-east direction, of low elevation (on average 50 m with some points below sea level) and with two great salt lakes: Êtang Saumatre, in Haiti, and Enriquillo Lake, in the Dominican Republic.

- Massif de la Hotte (Pic Macaya, 2,405 m) and Massif de la Selle (Pic or Morne La Selle, 2,680 m, the highest Haitian mountain) are in the Southern Peninsula. The Massif de la Selle is called Sierra de Bahoruco in the Dominican Republic. The Gonâve Island (Morne La Pierre, 776 m) belongs, in geological terms, to the Massif de la Selle. This southern group of mountains have a geology very different to the rest of the island.

- Llano Costero del Caribe (in English, "Caribbean Coastal Plain") is in the southeast of the island (and of the Dominican Republic). It is a large prairie east of Santo Domingo.

Rivers and lakes[change | change source]

The sources of the longest rivers of Hispaniola are in the mountains of the Cordillera Central (Dominican Republic) - Massif du Nord (Haiti).

The 10 longest rivers of the island are:[17]

- Artibonite. It is the longest river of the island and of Haiti. It is 321 km long (68 km in the Dominican Republic, 253 km in Haiti). Its sources are in the Cordillera Central and flows into the Gulf of Gonâve. Its watershed has an area of 9,013 km² (2,614 km² in the Dominican Republic, the rest in Haiti).

- Yaque del Norte. With 296 km, it is the second longest river of the island but the longest of the Dominican Republic. Its sources are in the Cordillera Central and flows to the Atlantic Ocean. Its watershed has an area of 7,044 km².

- Yuna. It is 209 km long. Its sources are in the Cordillera Central and flows to the east into Samaná Bay. Its watershed has an area of 5,498 km².

- Yaque del Sur. It is 183 km long and its sources are in the Cordillera Central. It flows to the south into the Caribbean Sea. Its watershed has an area of 4,972 km².

- Trois Rivières (Three Rivers). It is 150 km long and its sources are in the Massif du Nord and flows into the Atlantic Ocean.

- Ozama. It is 148 km long. Its sources are in Sierra de Yamasá (a branch of the Cordillera Central). It flows into the Caribbean Sea. Its watershed has an area of 2,685 km².

- Camú. It is 137 km long. Its sources are in the Cordillera Central and flows into the Yuna River. Its watershed has an area of 2,655 km².

- Nizao. It is 133 km long. Its sources are in the Cordillera Central and flows to the south into the Caribbean Sea. Its watershed has an area of 974 km².

- San Juan. It is 121 km long. Its sources are in the Cordillera Central and flows to the south into the Yaque del Sur River. Its watershed has an area of 2,005 km².

- Mao. It is 105 km long. Its sources are in the Cordillera Central and flows to the north into the Yaque del Norte River. Its watershed has an area of 864 km².

The largest lake of the Hispaniola, and of the West Indies, is the Lake Enriquillo. It is in the Hoya de Enriquillo with an area of 265 km². There are three small islands within the lake. It is around 40 meters below sea level and is a saline lake with a higher concentration of salt than the sea water.

The second largest lake, Étang Saumâtre (also known as Lake Azuei), is close to Lake Enriquillo but in Haiti, in the Cul-de-Sac. It is also a saline lake with an area of around 170 km².

Others lakes are Rincón (fresh water, area of 28.2 km²), Oviedo (brackish water, area of 28 km²), Redonda Limón, Étang de Miragoâne.

Climate[change | change source]

Hispaniola has a tropical climate but modified by elevation and the trade winds (winds that come from the northeast, from the Atlantic Ocean). At sea level, the average temperature is 25 °C, with small changes from one season to another. In the highest mountains, the temperature in winter can be as low as 0 °C.

There are two wet seasons: April-June and September-November. The most dry period is from December to March.

Rainfall varies greatly; eastern regions, like the Samaná Peninsula, get an average of over 2,000 mm in a year, but less than 500 mm fall in the southwest (Hoya de Enriquillo - Cul-de-Sac).

From June to November, hurricanes are frequent and can do much damage in the island.

Population[change | change source]

Hispaniola has a total population, estimated for July 2013, of 20,113,564 inhabitants, for a density of 263 inhabitants per km².

In Haiti, 95% of the population belongs to the black ethnic group,[10] and in the Dominican Republic it is about 70% of the population.[11]

In the Dominican Republic, only Spanish is spoken (except for groups of immigrants) even if Haitian Creole is gaining importance because the massive immigration from Haiti. Both French and (Haitian) Creole are spoken in Haiti, and both are official languages.

In both countries, the main religion is Roman Catholicism. Protestant groups are important, more in Haiti (15% of the population) than in the Dominican Republic (5%).

The most important cities in the island are Santo Domingo (capital of Dominican Republic), Port-au-Prince (capital of Haiti), Santiago (Dominican Republic), Carrefour (Haiti).

References[change | change source]

- ↑ Dardik, Alan, ed. (2016). Vascular Surgery: A Global Perspective. Springer. p. 341. ISBN 9783319337456. Retrieved 8 May 2017.

- ↑ Josh, Jagran, ed. (2016). "Current Affairs November 2016 eBook". p. 93. Retrieved 8 May 2017.

- ↑ Willey, Gordon R. (1976). The Caribbean Preceramic and Related Matters in Summary Perspective. San Juan, Puerto Rico: Fundación Arqueológica, Anthropológica e Histórica de Puerto Rico.

- ↑ García Valdez, Pedro (1963). The Ethnography of the Ciboney. New York: Cooper Square Pub. pp. 503–505.

- ↑ Veloz Maggiolo, Marcio (1972). Arqueología Prehistórica de Santo Domingo (in Spanish). Singapur: McGraw-Hill Far Eastern Publishers. p. 88.

- ↑ Las Casas, Bartolomé de (1965). Historia de las Indias (in Spanish). Mexico: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

- ↑ Columbus, Christopher (1989). The Diario of Christopher Columbus's First Voyage to America, 1492-1493. de las Casas, Bartolomé, Dunn, O.C., and Kelley, James E. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 9780806121017.

- ↑ Parry, J.H.; Sherlock, Philip (1976). Historia de las Antillas. Buenos Aires: Editorial Kapelusz. p. 9.

- ↑ Parry, J.H.; Sherlock, Philip (1976). Historia de las Antillas. Buenos Aires: Editorial Kapelusz. p. 21.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "CIA Factbook: Haiti". CIA Factbook. Archived from the original on 31 January 2016. Retrieved 20 May 2013.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 "CIA Factbook: Dominican Republic". CIA Factbook. Archived from the original on 13 February 2016. Retrieved 20 May 2013.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 De la Fuente, Santiago (1976). Geografía Dominicana. Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic: Editora Colegial Quisqueyana. pp. 90–92.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 Schutt-Ainé, Patricia; Staff of Librairie Au Service de la Culture (1994). Haiti: A Basic Reference Book. Miami, Florida: Librairie Au Service de la Culture. pp. 20. ISBN 0-9638599-0-0.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 As shown in a map made by Andrés Morales in 1508 and published in 1516. In Vega, Bernardo (1989). Los Cacicazgos de la Hispaniola. Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic: Museo del Hombre Dominicano. p. 88.

- ↑ Spadi, Fabio (2001). "Navassa: Legal Nightmares in a Biological Heaven". IBRU Boundary & Security Bulletin (Autumn): 115–130. Archived from the original on 2007-11-23. Retrieved 2007-09-19.

- ↑ Butterlin, Jacques (1977). Géologie Structural de la Région des Caraïbes (in French). Paris: Masson. pp. 110–111. ISBN 2-225 44979-1.

- ↑ De la Fuente, Santiago (1976). Geografía Dominicana. Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic: Editora Colegial Quisqueyana. pp. 110–114.